Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

International Journal of Psychological Research

Print version ISSN 2011-2084

int.j.psychol.res. vol.8 no.1 Medellín Jan./June. 2015

Intergroup anxiety, cultural sensitivity and socio-cultural diverse leaders' effectiveness

Ansiedad intergrupal, sensibilidad cultural y efectividad de líderes socioculturalmente diversos

María Laura Lupano Peruginnia,*, and Alejandro Castro Solanoa

a National Scientific and Technical Research Council CONICET, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

* Corresponding author: Maria Laura Lupano Perugini National Scientific and Technical Research Council CONICET, Mario Bravo 1259 (CP: C1175ABW), Buenos Aires, Argentina. Tel: 054-011-4855-8259, E-mail: mllupano@hotmail.com

Article history: Received: 25-06-2014 Revised: 20-09-2014 Accepted: 16-12-2014

ABSTRACT

This intended to analyze differences in the level of perception -of general population participants- in regards to leaders with diverse socio-cultural characteristics (gender, sexual orientation, religious affiliation, nationality) and also verify by means of structural equations, the influence of intergroup anxiety and the cultural sensitivity in terms of the level of effectiveness perception. Participants: 481 adults from Argentina (52.8% female, 47.2% male; age average = 35.45 years old). Instruments: Intergroup Anxiety scale, Cultural Sensitivity scale, and an ad hoc protocol designed to assess level of effectiveness perception in socio-culturally diverse leaders. Results: Differences in the level of perception of effectiveness according to sociocultural characteristics could not be confirmed. However, a direct effect of cultural sensitivity and an indirect effect of intergroup anxiety on the levels of effectiveness perception were confirmed. This work contributes to previous studies on prejudice and leadership.

Key words: Leadership, culture, intergroup anxiety, cultural sensitivity, effectiveness.

RESUMEN

Se propuso analizar diferencias en el nivel de percepción -de sujetos de población general- respecto de la efectividad de líderes con características socioculturales diversas (género, orientación sexual, afiliación religiosa, nacionalidad) así como comprobar, mediante ecuaciones estructurales, influencia de la ansiedad intergrupal y la sensibilidad cultural sobre el nivel de percepción de efectividad. Participantes: 481 sujetos adultos argentinos (52.8% mujeres, 47.2% varones; promedio de edad = 35.45 años). Instrumentos: Escala de ansiedad intergrupal, Escala de sensibilidad cultural, Protocolo diseñado ad hoc para evaluar nivel de percepción de efectividad de líderes socioculturalmente diversos. Resultados obtenidos: no se pudo confirmar diferencias en el nivel de percepción de efectividad según características socioculturales. Sin embargo, se confirmó efecto directo de la sensibilidad cultural, e indirecto de la ansiedad intergrupal, sobre los niveles de percepción de efectividad. Este trabajo contribuye al estudio sobre prejuicios en relación al liderazgo.

Palabras clave: liderazgo, cultura, ansiedad intergrupal, sensibilidad cultural, efectividad.

1. INTRODUCTION

Today's world of work is characterized by its global dimension. Markets' globalization, new technologies' impact, the move of companies to other countries and the subsequent migration of management and subordinate staff, results in the study of variables that are related to the working environment (Karahanna, Evaristo & Srite, 2005; Thomas, 2008). Some authors suggest that in order to act efficiently, people need to be interested in getting in touch with other people from diverse cultural groups and be sensitive to the differences within their own and the others' culture. (Chrobot-Mason, Ruderman & Nishii, 2013; Fowers & Davidov, 2006; Hammer, Bennett & Wiseman, 2003). This has an impact in the world of work in general and particularly in the phenomenon of leadership. Chin (2010) highlights the need of expanding on the present leadership theories in order to include issues pertaining equity, diversity and social justice. According to the author, in leadership publications only 200 out of 2207 include any kind of cultural issue. This reveals the tendency to give an ethnocentric look to the problem (Zweigenhaft & Domhoff, 2006).

The above indicates that a different perspective is being drawn in leadership matters in which it is frequent to find women, people from other nationalities, ethnicities, and cultural and religious groups, striving to occupy the highest work positions (Sanchez-Hucles & Davis; 2010). All this has also been favored by macro-contextual situations that, in recent times, have boosted policies that promote equity and equality not only in ethnic and cultural matters, but also in the sense of finding equal opportunities for people with disabilities and different sexual orientations; for instance, Argentina's enactment of egalitarian civil union (among people from the same gender).

Thus, it is interesting to analyze the impact generated by the inclusion of these minorities in the field of leadership (Chin, 2013; Eagly & Chin, 2010; Fassinger, Shullman & Stevenson, 2010).

Nevertheless, if well it is true that legislative international policies instill higher equity and equality of opportunities, statistics usually do not reflect the inclusion of such minorities in higher positions. For instance, in Argentina, country where this study was conducted, women occupy 22% of management positions, but only 1% gets the CEO -Chief Executive Officer- position (Casas, 2010). In the United States women occupy the 23% of executive positions, while 5% are occupied by Hispanic, and 4% by Afro and Asian descents despite the high academic scores obtained by the latter group (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2009; Chin, 2013).

Such data is relevant since by 2050 the ethnic racial minorities are expected to increase from a 28% to a 50% in the United States (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010). This tendency can be generalizable to other countries. In regards to other minorities, in Argentina the law requires companies to include 4% of the people with disabilities (who are qualified for the position) in most companies' staff (law 22.431). Even so, these people do not get high positions. Other avatars affect sexual minorities (gays, lesbians and transsexuals) and discrimination in jobs' positions is frequent (Chin & Sanchez-Hucles, 2007; Fassinger et al., 2010).

Studies carried out to explain the reasons behind such unequal incorporation aim at considering that the imposed barriers on those minorities are the product of prejudice and discriminatory attitudes towards them (e.g. Ayman & Korabik, 2010; Chin, 2009, 2010; Eagly & Carli, 2007; Fassinger et al., 2010; Lupano Perugini, 2011; Sanchez-Hucles & Davis, 2010;).

Research and prejudice reduction becomes relevant since it has been objectively proven that an increase of minorities' inclusion such as women or racial groups can also increase the levels of performance, innovation and productivity in organizations (Deszõ & Ross, 2012; Richard, McMillan, Chadwick, & Dwyer, 2003).

Contrary to this, the existence of the mentioned above violates personal satisfaction in work environments on the part of those belonging to minorities (Fiske & Lee, 2008).

There are diverse theoretical models that help explain prejudice. Nowadays, it is subtly expressed than before as analyzed in aversive racism (Gaertner & Dovidio, 1986) or ambivalent (Katz, 1981). A socio-cognitive perspective known as Information Processing, claims that both, leaders and followers possess a script - implicit theories - which would delineate the behaviors of a person in order for s(he) to be considered a leader (Wofford, Godwin & Wittington, 1998). Prejudices arise when people hold stereotypes that are incompatible with leadership roles (Eagly & Diekman, 2005). Beyond the fact that there might be differences according to context in which the leader acts (Lord, Brown, Harvey & Hall, 2001), generally speaking, leadership has been associated to Caucasian male stereotype (Rosette, Leonardelli & Phillips, 2008), let alone the higher number of research studies originating in North America (Den Hartog & Dickson, 2004).

This is how the leader's prototype is usually characterized by attributes such as power, ambition, dominance, etc. In line with this, a study conducted in Argentina (Castro Solano, Becerra & Lupano Perugini, 2007), determined the characteristics that are commonly associated with an effective leader (e.g., ideals and values; effectiveness and obtained results; perseverance; achievement in adverse circumstances; capacity of ascending on staff; academic performance; innovation; among others).

Because leadership is frequently associated with male gender, theories that intend to explain the phenomenon have emerged. The Role Congruity Theory proposed by Eagly and Karau (2002) states that women are usually perceived negatively when trying to occupy leading positions by virtue of the incongruity with their gender's attributes, mainly communal (e.g., protection), and those expected for such positions: agent attributes (e.g., dominance), which forces them to adopt an androgen style to be perceived as effective leaders (Eagly & Karau, 2002; Lupano Perugini & Castro Solano, 2008, 2013). The same difficulties would be faced by gay men since many are perceived with many female stereotype attributes (Fassinger et al., 2010; Malden, Blackwell & Madon, 1997). In the case of ethnic minorities, these are also influenced by stereotypical perceptions that move away from the ideal leader's prototype. For instance, African-Americans are perceived as people who lack skills; Latin people are seen as less qualified and ambitious; and Asians, as too passive and little assertive (Dixon & Rosenbaum, 2004; Kawahara, Pal & Chin, 2013; Madon et al., 2001; Niemann, Jennings, Rozelle, Baxter & Sullivan, 1994).

In virtue of the stereotypical perceptions mentioned above, it is relevant to analyze the emotional responses that intergroup contact can generate among members of diverse cultural characteristics since, according with Stephan and Stephan (1985), the experience of states of anxiety can generate the feeling of threat and result in perceptions and negative attitudes towards those causing them. This could explain the origin of discriminatory actions upon minorities (Eagly & Chin, 2010; Klein & Wang, 2010). This allows us to assert that, in order to instill the inclusion of people with diverse cultural characteristics in the highest work positions, it is necessary to decrease the ruling ethnocentrism in leadership matters in such way, that stereotypical perceptions and hostile behaviors towards minorities can be decreased (Duckitt, Callaghan & Wagner, 2005).

Therefore, it is necessary to work on diversity acceptance, which as stated by Cox (1993), can be affected by factors at an individual level (identity, prejudice, stereotype and personality); group factors (cultural differences, ethnocentrism, intergroup conflict) and factors at the organizational level (interaction, institutional bias). Showing higher levels of cultural sensitivity, understood as the acceptance and tolerance towards diversity (Bennett & Benett, 2004), could generate a higher predisposition to perceive and accept leaders with diverse cultural characteristics in a more positive manner, for people who present them seem to be more ethno relative and endowed with higher tolerance towards those aspects in their environment which differ from their own values and beliefs.

A research conducted in Argentina showed a positive relation between the levels of sensitivity and positive attitudes towards multiculturalism and also a negative relation between sensitivity and the levels of intergroup anxiety (Castro Solano, 2009). This results interesting when analyzed in a Latin American context since its countries are characterized by a wide cultural diversity. However, the levels of immigrants' acceptance tend to be low. For example, the survey of Regional Integration Opportunities of Latinobarómetro Corporation revealed that seven out of 10 Latin Americans reject immigrants who are poor or have a different race.

Uruguay holds the first place among the most open to the arrival of people from poorer countries with a 27%, followed by México and Nicaragua, with a 22%. Ecuator (4%) and Paraguay (7%)

Are the most closed in this sense and to the allowance of opportunities for foreigners from a different race to live in their country. In this variable, Uruguay (30%) is once again the most receptive, followed by Argentina, Colombia and Nicaragua, with a 20% (Latinobarómetro, 2008).

From a different perspective, 20% of Latin Americans also claim to be discriminated in some aspect (Latinobarómetro, 2011). A research conducted in Argentina attempting to analyze the level of acceptance of foreign students revealed that people tended to assign positive attributes to students from other nationalities to the detriment of the negative. In any case the best evaluated foreigners where those coming from other Latin or European countries as opposed to the African and Asian students who had the worst evaluations (Castro Solano, 2013).

As a result of this, one can highlight the relevance of carrying out this type of research since if well it is true that there is good amount of research carried out in regards to gender issues (Eagly & Karau, 2002; Eagly & Carli, 2007; Lupano Perugini, 2011), there is little related to other minorities (Chin, 2010). On the other hand, a lot has been studied about racism and prejudice towards diverse ethnic groups, yet little has been done related to leadership (Hodson, Dovidio & Gaertner, 2004). This allows us to set the following objectives:

- To verify if there are differences in the level of effectiveness perception of leaders with diverse socio-cultural characteristics according to type (gender, sexual orientation, religious affiliation, nationality).

- To analyze, by means of a structural equations model, if there is influence from intergroup anxiety and cultural sensitivity on the level of effectiveness perception of leaders with diverse socio-cultural characteristics.

From the records it is expected to find differences in the level of perception of effectiveness, being higher for the prototypical case (male leader). Besides, it is also expected to prove an influence of intergroup anxiety and cultural sensitivity on the level of effectiveness perception of leaders with socio-cultural diverse characteristics.

2. METHOD

2.1 Participants

A nonprobability sample was used. Voluntarily, 481 people participated who were adults from the general population: 227 male (47.2%) and 254 female (52.8%), and who were 35.45 years old (DS = 12.7) in average.

A 19.5% (n = 94) had basic schooling (elementary and/or high school). The remaining percentage (80.5%, n = 387) had other studies such as university or postgraduate studies.

As for their occupation, 71.3% (n = 343) were employees; 13.9% (n = 67) were managers or employers; 7.7% (n = 37) were self-employed; a 1.3% (n = 6) were masons, housekeepers or non paid workers; the remaining percentage (5.6%; n = 27) were unemployed or did not work; a 0.2% (n = 1) did not give any data. Out of the total of participants, 33.1% (n = 159) occupied a leadership position and was in charge of personnel while 66.9% (n = 322) were subordinate.

The majority of the participants (96.3%; n = 463) lived in Buenos Aires while 2.5% (n = 12) lived inside Argentina. The remaining percentage (1.2%, n = 6) did not give information about the place where they lived.

The highest percentage (71.5%, n = 344) described itself as belonging to middle class in the society; 17.5% (n = 84) high or middle-high class; 10.1% (n = 49) middle-low or low class, and 0.8% (n = 4) did not give any data.

In line with the purpose of this study, it is relevant to clarify some additional information of the analyzed sample. In terms of religious practices, 56% (n = 269) said they were Catholic; 5.2% (n = 25) Jewish; 4.4% (n = 21) Atheist; 1.5% (n = 7) Evangelist; 1% (n = 5) Buddhist and 0.4% (n = 2) Protestant. Besides this, only one participant claimed to be Muslim and a high percentage (31,4%; n = 151) did not give information about religious affiliation or answered, "none". Participants did not belong to racial/ethnic groups and there is no information regarding sexual orientation.

2.2 Materials

Intergroup Anxiety Scale (Stephan & Stephan, 1985; Castro Solano, 2011 Adaptation): It consists of a measurement for anxiety of diverse cultural groups. It has to do with adjectives that indicate whether the person is perceived with higher or lower anxiety when having contact with diverse cultural groups.

Twelve (12) adjectives were used and the evaluated person was to answer items in a scale with a Likert format of 7 points (from nothing to a lot), degree in which the contact with foreigners elicited positive emotions (e.g., comfortable, calm, safe) and negative (e.g., stressed, threatened, anxious) referred by the adjectives. For the purposes of this study, first the items corresponding to positive emotions were switched (items 2, 4, 6, 10, 12) and then, an added score was calculated (items' average) for all the adjectives. The reliability obtained was 0.86. A higher score indicates a higher perception of anxiety; this means that the person experiences negative emotions with a higher intensity when in contact with foreigners.

Cultural Sensitivity Scale (ESEC) (Castro Solano, 2009): It is a designed scale to assess the degree of understanding and people's acceptance of the different aspects of a culture. It presents 11 items that correspond with a Liker's 5 points scale. It has two dimensions:

- Cultural Consciousness (items 1, 3, 4, 5, 7, 9, 11): It assesses the degree of acceptance of cultural differences.

- Cultural Uniformity (items 2, 6, 8, 10): It assesses the extent to which people relativize cultural differences.

The reliability obtained for each of the dimensions in the study that describes the design and instrument validity (Castro Solano, 2009) is acceptable, being 0.74 for the Cultural Consciousness dimension, 0.68 for the Cultural Uniformity dimension and 0.66 for the whole scale. In order to estimate the global level of sensitivity towards cultural differences, it is necessary to calculate an average. Prior to such estimate, the Uniformity dimension items need to be switched in such a way, that a higher score indicates higher sensibility. A high cultural sensibility indicates a higher degree of acceptance and cultural diversity.

Case Vignettes: A protocol containing five case vignettes was designed. The same were designed ad hoc for the present study. Such vignettes presented the description of an efficient leadership case, in which some socio-cultural characteristic varied: namely, the gender, sexual orientation, religious affiliation or nationality (cultural heritage). As suggested in prior studies (e.g., Bertrand & Mullainathan, 2004; Rosette, et al., 2008) names that were typically associated to the minorities in question were chosen (e.g. Abdul for the case of religious affiliation). In accordance with the research mentioned in the introduction - carried out in Argentina- (see Castro Solano, Becerra & Lupano Perugini, 2007) the vignettes included the characteristics associated to an effective leader (e.g., ideals and values; effectiveness and obtained results; perseverance; achievements in adverse situations; capacity of ascending on staff; intellectual skills; innovation; among others).

After the reading of the vignettes, the evaluated person was to mark his/her score according to four statements that were presented next to them and that inquired the degree of effectiveness perception of the described leaders (see Dario's case sample). The content and adaptation of the vignettes was previously tested by a group of experts in the same topic accounting for the validity of them.

The following excerpt shows, in the manner of an example, the vignette corresponding to a case in which the variation regarding sexual orientation was introduced:

"Darío is the manager of credit in a bank, he is an accountant, he is forty years old, he is homosexual and he lives with his partner. He stands out among other managers for the results obtained to this point and his intellectual skills, being recognized by his bosses as one of the most qualified managers. He is a very formal kind of person, looking sharp and neat. His employees remember that even when he was not a director, he had been assigned the job of collecting a past-due loan portfolio, task in which others would have systematically failed. Dario, despite the fact that firstly, could not obtain the goals he had set for himself, little by little had the clients pay their debts. He used an innovating system: He would give customers an appointment; calculated what they owed the bank, and instead of charging them over the due interests, he told them that he would give them a very beneficiary discount if they paid right away, which would set them free from their debts once and for all. This is how he was able to recover customers that were "non chargeable". This achievement earned him the actual manager position he holds. He is always very straightforward, honest, and he never shows off his qualities. Dario is very well respected and appreciated by his subordinates; he thinks that it is important to treat collaborators properly in order for them to have loyalty to the company and keep a positive working climate".

Following the vignette, the evaluated person was to answer in a scale from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree) to four statements that inquired on the level of effectiveness that was perceived as for the described leader ("He is a very good leader"; "I completely identify with Dario's actions"; "Dario is an effective leader"; "Dario's personal characteristics coincide with what I think a good leader should be like).

The reliability for each of the vignettes was calculated obtaining acceptable levels ranging from .82 to .90. The lowest reliability was obtained for the case that represented a leader with different religious affiliation, and the highest for the prototypical case -just as suggested in the introduction (e.g., Rosette, Leonardelli & Phillips, 2008); the leadership prototype is usually associated to male gender, reason why the prototypical case corresponds with the male leader.

2.3 Procedure

Protocols were administered by students from the Psychology program of a university located in Autonoma city in Buenos Aires, and they where carrying out their professional practices in research. A researcher supervised their work. Participants did not receive any economic incentive for their contribution. The booklet that contained the tests had an introduction on the cover soliciting consent from the participant and ensuring the anonymity of his/her information and the exclusive use of it for research purposes. The collection and data analysis was carried out through SPSS 13.0 and AMOS 16.0; the design employed was intra-subject.

3. RESULTS

In first place, there was an attempt to determine if there exist statistically significant differences in the level of effectiveness perception according to the type of socio-cultural characteristics present in the leader described in the vignettes. For such purpose an analysis in the univariate variance (ANOVA) was conducted, in which the total of the punctuations assigned to the vignette items was included as a dependent variable, and as a factor, the type of vignette. This is, the cases exposed in each of the vignettes were considered as the comparison groups. The cited analysis did not throw significant differences among the measurements of each group [F(4,476)=1.22, p>.05]. The highest measurement was obtained for the male leader (M = 4.10; DE= .84) and the lowest for the leader with different and strong religious affiliation (M = 3.93; DE= .79).

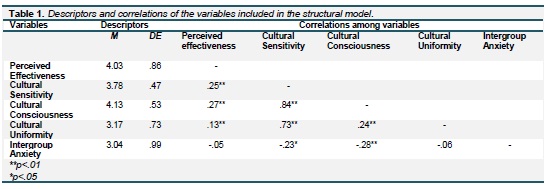

In second place, the measurements and correlations among all the variables were calculated for the purpose of verifying the strength of the relations among the variables included in the model that was tested on the following step. In relation to the levels of effectiveness perceived, a global score corresponding to all the vignettes was considered. Besides, for the sub dimension Cultural Uniformity, the items were previously switched (see materials).

Generally speaking, what can be observed is that the lowest measurement (considering the range of answer options that was used for measuring each variable) was obtained in the levels of intergroup anxiety, while for other variables the levels are middle-high. As for the obtained correlations, a significant relation between the global score corresponding to the level of cultural sensitivity and the level of perception of leaders' effectiveness with socio-cultural diverse characteristics was evidenced. Likewise significant correlations with the sub-dimensions corresponding to cultural sensitivity (Cultural consciousness and Cultural uniformity) were obtained. It has to be noted that the obtained correlations present a size of the small effect (r<.30) (Cohen, 1992). If well it is true that the values found are low, they indicate that the people who have higher acceptance and tolerance to diversity (Bennett & Benett, 2004), tend to perceive leaders with diverse socio-cultural characteristics as effective. In relation to intergroup anxiety and the level of perception of effectiveness, there was no significant relation among such variables.

3.1 Structural Model

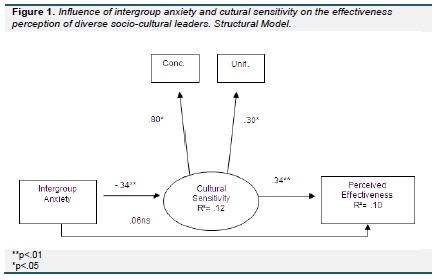

In third place and taking into account the consulted records, which show that both, anxiety and cultural sensitivity (e.g., Bennet & Bennet, 2004; Fowers & Davidov, 2006; Hammer, Bennett & Wiseman, 2003, Stephan & Stephan, 1985) can influence the perception of effectiveness of socio-cultural diverse leaders, a model was tested in which there was a hypothesis of a direct effect of cultural sensitivity on the perception of effectiveness and an indirect effect of intergroup anxiety on effectiveness having sensitivity as a mediating variable. The determination on the type of effect (direct or indirect) on the levels of effectiveness perceived was hypothesized from the results obtained in the prior analysis: on this analysis there was not relation found between intergroup anxiety and perceived effectiveness; on the contrary, a significant relation between sensitivity and effectiveness, and between sensitivity and anxiety was evidenced.

Intergroup anxiety is an observed exogenous variable; the perceived effectiveness is an endogenous variable while the cultural sensitivity is a latent endogenous variable whose indicators are consciousness and cultural uniformity. The exposed theoretical model and its adjustment to empirical data were tested by means of structural equations. The degree of adjustment of the theoretical model to the data of the sample through the AMOS Graphics 16.0. program was calculated. The evaluation of the adjustment aims at determining whether the relations among the variables of the estimated model accurately reflect the relations observed in the data (Weston & Gore, 2006). The parameters of the original model were estimated following the Maximum Plausibility criterion. The information provided by six of the most used adjustment indexes was collected (Byrne, 2001; García-Cueto, Gallo & Miranda, 1998; Hu & Bentler, 1999): L2; u2/gl; GFI (Goodnes of Fit Index); AGFI (Adjusted Goodnes of Fit Index); NFI (Normed Fit Index); CFI (Comparative Fit Index) and RMSEA (Root mean square error of approximation).

For this task, the values used for the goodness of fit model are the following: The ratio chi square over the degrees of freedom with values under 3 (Kline, 2005); for the CFI and GFI indexes and values between .90 and .95 or higher are considered as acceptable adjustment, excellent for the model and finally, in the case of RMSEA values between .05 and .08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999) are the expected ones.

The mentioned indicators showed that the data adjusts optimally to the model (x2= 1.933, p = .16; L2/gl= 1.99 ; GFI= .99; AGFI= .98; NFI= .98; CFI= .99; RMSEA= .05). Figure 1 shows the standardized path coefficients and the determination coefficients (R2). The model lets us see that intergroup anxiety does not have a direct effect on the level of effectiveness perception (β = -.06, ns). Nevertheless, the intergroup anxiety directly influences cultural sensitivity (β = -.34, p<.01) explaining a 12% of the variance of the latter, which, in turn influences the level of perceived effectiveness (β = -.34, p<.05), which explains the 10% of the variance of this last variable. Therefore, an indirect effect of intergroup anxiety on the perceived effectiveness can be considered (-.34 x .34 = -.12).

4. DISCUSSION

The present study intended to show, in the first place, whether people occupying a leading position could be perceived differently by virtue of their socio-cultural characteristics. The findings do not allow confirming such hypothesis. From the records consulted and other research studies carried out in the context of the study -Argentina- as cited in the introduction, one could infer that the particularities of the analyzed context could explain the obtained results.

Argentina is characterized for being a culturally diverse country that continues to grow. Historically, it has housed a large number of immigrants coming from Europe, and in the last decades, the inhabitants from bordering countries have found good work and academic growth opportunities in the region. If the findings cited in the Latinbarómetro show that the Latin American context is reluctant to sheltering people with diverse cultural traditions, Argentina occupies the second place among the most open countries. This is reflected in the present study given the low intergroup anxiety and the middle-high levels of cultural sensitivity and effectiveness perception obtained in the analyzed sample. In any case, taking into account that the lowest levels of perception were obtained in the case of a leader with very marked religious characteristics, it would be interesting to analyze, in further research, whether the low frequency of contact (since the leader described represents a cultural group that is frequently low in Argentina) and the big cultural gap between the mainstream cultural characteristics in the subordinates and that of the leader could have some type of influence (Berry, 2006; Pettigrew & Tropp, 2000). According to the obtained results, the Argentinian sample analyzed does not present low levels of effectiveness perception as for female leaders or those belonging to sexual minorities or different ethnics.

Probably, the socio-political context could be accounted for these results since, as explained in the introduction, certain legal dispositions (e.g., egalitarian marriage) could give way to a higher visibility and acceptance to social level. If well it is true that the obtained differences have not been significant, it is relevant to mention that the leader who has received the best evaluations in the present study is the male leader, confirming that the prototype of effective leader continues to be associated with male gender (Eagly & Karau, 2002; Rosette, Leonardelli & Phillps, 2008).

As for the second hypothesis, this could be confirmed since it has been proved that showing a higher tolerance and acceptance to diversity, contributes to perceiving in a more efficient manner those leaders with different socio-cultural characteristics. Besides, evidence was found that although experiencing negative emotions vis-à-vis diversity does not influence the perception of effectiveness, indirectly it does, for it has effect on the levels of cultural sensitivity. The hypothesized in the model could be confirmed, yet the variance explained is little, which lets us assume that other variables that were not included could have incidence (Pérez, Medrano & Sánchez Rosas, 2013).

In further studies, it would be appropriate to widen the model incorporating variables such as the listed above (e.g., contact frequency, cultural distance). Likewise, some particularities such as type or organization in which the leader works or the staff distribution are relevant aspects since they have proven to have influence; for instance, getting a higher level of acceptance towards female leaders (e.g., Cuadrado, Navas & Molero, 2006; Lupano Perugini & Castro Solano, 2013). It would also be interesting to analyze the levels of effectiveness perception in terms of social class or status of the participant; this is, whether s(he) fulfills the stereotypical profile (e.g., male leader) or he makes part of a counter-stereotypical group (e.g., a minority leader).

It is important to note that, one of the limitations of this study is related to the chosen modality to assess the levels of perception since it was carried out with a paper and pencil protocol by means of ad hoc designed vignettes. Such modality can cause participants' answers to be influenced by social desirability, which could lead people to answer what is socially expected from them. For this reason, in future studies it would be convenient to use other observable modalities such as practices in simulated environments or focus groups, in which possible distortions to questions' answers could be easily detected.

The present study allows for opening and widening the landscape in terms of research on leadership since in both, international and local -Argentina- contexts, there is background in regards to how leaders succeed in adjusting to culturally different environments (e.g. Castro Solano, 2011) or in relation to the challenges that females face to have access to leading position (e.g., Lupano Perugini, 2011), but there are few studies that focus their analysis from the subordinate's perspective or that combine different socio-cultural characteristics of the leaders (such as, gender, sexual orientation, religious affiliation, nationality, and others).

5. REFERENCES

Ayman, R., & Korabik, K. (2010). Leadership: Why gender and culture matter. American Psychologist, 65, 157-170. [ Links ]

Bennett, J.M. & Bennett, M.J. (2004). Developing intercultural Sensitivity: An Integrative Approach to Global and domestic Diversity. In D. Landis, J.M. Bennett & M.J. Bennett (Eds.). Handbook of Intercultural Training (pp. 147-166). California: Sage. [ Links ]

Bertrand, M., & Mullainathan, S. (2004). Are Emily and Greg more employable than Lakisha and Jamal? A field experiment on labor market discrimination. The American Economic Review, 94(4), 991-1013. [ Links ]

Berry, J. W. (2006). Mutual attitudes among immigrants and ethnocultural groups in Canada. International of Journal of Intercultural Relations, 30 (6), 719-734. [ Links ]

Byrne, B. M. (2001). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. [ Links ]

Carr, S. C. (2011). A Global Community Psychology of Mobility. Psychosocial Intervention, 20, 3193-25. DOI:10.5093/in2011v20n3a8. [ Links ]

Casas X. (2010). Hay más jefas pero pocas llegan a ser CEO. Recuperado el 21 de marzo de 2011 de http://www.iae.edu.ar/iaehoy/Documents/NG_20100308_Cronista_Debeljuh_MujeresLideres.pdf. [ Links ]

Castro Solano, A. (2009). La evaluación de la sensibilidad cultural. Un estudio preliminar con estudiantes extranjeros. Acta Psiquiátrica y Psicológica de América Latina, 55 (4), 229-238. [ Links ]

Castro Solano, A. (2011). Estrategias de aculturación y adaptación psicológica y sociocultural de estudiantes extranjeros en la argentina. Interdisciplinaria, 28(1), 1-16. [ Links ]

Castro Solano, A. (2011). La evaluación de las competencias culturales de los líderes mediante el Inventario de Adaptación Cultural. Anales de Psicología de la Universidad de Murcia, 27(2), 507-517. [ Links ]

Castro Solano, A. (2013). Predictores de las relaciones interculturales con estudiantes universitarios extranjeros. Acta Psiquiátrica y Psicológica de América Latina, 59 (2), 104-113. [ Links ]

Castro Solano A., Becerra L. & Lupano Perugini, M.L. (2007). Prototipos de liderazgo en población civil y militar. Interdisciplinaria, 24, 1, 65- 94. [ Links ]

Cuadrado, I. Navas, M. & Molero, F. (2006). Mujeres y Liderazgo. Claves Psicosociales del Techo de Cristal. Madrid: Sanz y Torres. [ Links ]

Chin, J. L. (2009). Diversity in mind and in action. Westport, CT: Praeger. [ Links ]

Chin J.L. (2010). Introduction to the Special Issue on Diversity and Leadership. American Psychologist, 65(3), 150-156.

Chin, J. L. (2013). Introduction: Special section on Asian American leadership. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 4 (4), 235-239. DOI: 10.1037/a0035144. [ Links ]

Chin, J.L. & Sánchez-Hucles, J. (2007). Diversity and leadership. American Psychologist, 62(6), 608-609. [ Links ]

Chrobot-Mason, D., Ruderman, M.N. & Nishii, L.H. (2013). Leadership in a diverse workplace. In: R. M. Quinetta (Ed), The Oxford handbook of diversity and work (pp. 315-340). New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press [ Links ]

Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155-159. DOI:10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155. [ Links ]

Cox, T. (1993). Cultural diversity in organizations. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler. [ Links ]

Den Hartog, D. N., & Dickson, W. (2004). Leadership and culture. In J. Antonakis, A. T. Cianciolo, & R. J. Sternberg (Eds.), The nature of leadership (pp. 249-278). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Dezsõ, C. L. & Ross, D. G. (2012). Does female representation in top management improve firm performance? A panel data investigation. Strat. Mgmt. Journal, 33, 1072-1089. doi: 10.1002/smj.1955. [ Links ]

Dixon, J., & Rosenbaum, M. (2004). Nice to know you? Testing contact, cultural, and group threat theories of anti-Black and anti-Hispanic stereotypes. Social Science Quarterly, 85(2), 2004. [ Links ]

Duckitt, J., Callaghan, J., & Wagner, C. (2005). Group identification and outgroup attitudes in four South African ethnic groups: A multidimensional approach. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31, 633-646. [ Links ]

Eagly, A.H. & Carli L.L. (2007). Through the labyrinth. The truth about how women become leaders. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. [ Links ]

Eagly, A.H. & Chin, J.L. (2010). Are memberships in Race, Ethnicity, and Gender categories merely surface characteristics? American Pychologist, 65(9), 934-935. DOI: 10.1037/a0021830. [ Links ]

Eagly, A. H. & Karau, S. J. (2002). Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychological Review, 109, 573- 598. [ Links ]

Eagly, A. H., & Diekman, A. B. (2005). What is the problem? Prejudice as an attitude-in-context. In J. F. Dovidio, P. Glick, & L. Rudman (Eds.), On the nature of prejudice: Fifty years after Allport (pp. 19-35). [ Links ]

Fassinger, R. E., Shullman, S. L., & Stevenson, M. R. (2010). Toward an affirmative lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender leadership paradigm. American Psychologist, 65, 201 -215. [ Links ]

Fiske, S.T. & Lee, T.L. (2008). Stereotypes and prejudice create workplace discrimination. In P. Brief (Ed.), Diversity at work (pp 13-54). New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Fowers, B. & Davidov, B. (2006). The virtue of multiculturalism. Personal transformation, character and openness to the other. American Psychologist, 61(86), 581-594. [ Links ]

Gaertner, S. L., & Dovidio, J. F. (1986). The aversive form of racism. In J. F. Dovidio & S. L. Gaertner (Eds.), Prejudice, discrimination, and racism (pp. 61-89). Orlando, FL: Academic Press. [ Links ]

García-Cueto, E., Gallo, P. & Miranda, R. (1998). Bondad de ajuste en el análisis factorial confirmatorio. Psicothema, 10, 717-724. [ Links ]

Hammer, M., Bennett, M. & Wiseman, R. (2003). Measuring intercultural sensitivity: the intercultural development inventory. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 27, 421-443. [ Links ]

Hodson, G., Dovidio, J. F., & Gaertner, S. L. (2004). The aversive form of racism. In J. L. Chin (Ed.), The psychology of prejudice and discrimination: Vol. 1. Racism in America (pp. 119-136). Westport, CT: Praeger. [ Links ]

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1 -55. [ Links ]

Karahanna, E. -Evaristo, J.R. -Srite, M. (2005): Levels of culture and individual behavior: An integrative persepctive. Journal of Global Information Management, 13(2), 1-20. [ Links ]

Katz, I. (1981). Stigma: A social psychological analysis. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [ Links ]

Kawahara, D. M., Pal, M., & Chin, J. L. (2013). The leadership experiences of Asian Americans. Asian American Journal of Psychology. Advance online publication. [ Links ]

Klein, K. M., & Wang, M. (2010). Deep-level diversity and leadership. American Psychologist, 65, 932-933. DOI:10.1037/a0021355. [ Links ]

Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford. [ Links ]

Latinobarómetro (2008). Oportunidades de Integración Regional II. Recuperado de http://www.latinobarometro.org/docs/OportunidadesDeIntegracionIICAFLimaPeru_Abril_16_2008.pdf. [ Links ]

Latinobarómetro (2011). Informe 2011. Recuperado de http://www.infoamerica.org/primera/lb_2011.pdf. [ Links ]

Lord, R. G., Brown, D. J., Harvey, J. L., & Hall, R. J. (2001). Contextual constraints on prototype generation and their multilevel consequences for leadership perceptions. The Leadership Quarterly, 12, 311-338. [ Links ]

Lupano Perugini, M. L. (2011). Liderazgo, género y prejuicio. Influencia de los estereotipos de género en la efectividad del liderazgo femenino y actitudes hacia las mujeres líderes. Tesis Doctoral. [ Links ]

Lupano Perugini, M. L. & Castro Solano A. (2008). Liderazgo y género. Identificación de Prototipos de liderazgo efectivo. Perspectivas en Psicología, 5(1), 69-77. [ Links ]

Lupano Perugini, M.L. & Castro Solano, A. (2013). Estereotipos de género, sexo del líder y del seguidor: su influencia en las actitudes hacia mujeres líderes. Revista de Psicología 9(17), 87-104. [ Links ]

Madon, S., Guyll, M., Aboufadel, K., Montiel, E., Smith, A., Palumbo, P., & Jussim, L. (2001). Ethnic and national stereotypes: The Princeton trilogy revisited and revised. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27, 996-1010. [ Links ]

Malden, MA, Blackwell & Madon, S. (1997). What do people believe about gay males? A study of stereotype content and strength. Sex Roles, 37, 663-685. [ Links ]

Niemann, Y. F., Jennings, L., Rozelle, R. M., Baxter, J. C., & Sullivan, E. (1994). Use of free responses and cluster analysis to determine stereotypes of eight groups. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 20, 379-390. [ Links ]

Pérez, E., Medrano, L. A. & Sánchez Rosas, J. (2013). El Path Analysis: conceptos básicos y ejemplos de aplicación. Revista Argentina de Ciencias del Comportamiento, 5 (1), 52-56. [ Links ]

Pettigrew, T.F. & Tropp, L. (2000). Does integroups contact reduce prejudice: Recent meta-analytic findings. In: S. Oskamp (Ed.), Reducing prejudice and discrimination (pp. 93-114). Mahwah. NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. [ Links ]

Richard, O., McMillan, A., Chadwick, K., & Dwyer, S. (2003). Employing an innovation strategy in racially diverse workforces. Group & Organization Management, 28, 107-126. [ Links ]

Rosette, A.S., Leonardelli, G.J. & Phillips, K.W. (2008). The white standard: racial bias in leader categorization. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93 (4), 758-777. DOI: 10.1037/0021-9010.93.4.758. [ Links ]

Sanchez-Hucles, J. V., & Davis, D. D. (2010). Women and women of color in leadership: Complexity, identity, and ntersectionality. American Psychologist, 65, 171 -181. [ Links ]

Stephan, W. G & Stephan, C. (1985). Intergroup anxiety. Journal of Social Issues, 41, 157-176. [ Links ]

Thomas, D.(2008). Cross-cultural management. Essential Concepts. Londres: Sage. [ Links ]

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2009, January). Household data annual averages: Employed persons by detailed occupation, sex, race, and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity. Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat11.pdf. [ Links ]

U.S. Census Bureau. (2010). Statistical abstract of the United States: 2010 (129thed.) Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/. [ Links ]

Weston, R. & Gore Jr., P. A., (2006). A Brief Guide to Structural Equation Modeling. The Counseling Psychologist, 34; 719-751. [ Links ]

Wofford, J., Goodwin, V. L. & Wittington, J. (1998). A field study of a cognitive approach to understanding transformational and transactional leadership. Leadership Quarterly. 9, 55-84. [ Links ]

Zweigenhaft, R. L., & Domhoff, G. W. (2006). Diversity in the power elite: How it happened, why it matters. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. [ Links ]