Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

International Journal of Psychological Research

Print version ISSN 2011-2084

int.j.psychol.res. vol.8 no.1 Medellín Jan./June. 2015

Examining Materialistic Values of University Students in Thailand

Examen de los valores materialistas de Estudiantes Universitarios en Tailandia

Tanakorn Likitapiwata,*, Wilailuk Sereetrakulb, and Saovapa WichadeeC

a Faculty of Commerce and Accountancy Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand.

b Faculty of Education, Bangkokthonburi University, Bangkok, Thailand.

b Language Institute, Bangkok University, Bangkok, Thailand.

* Corresponding author: TanakornLikitapiwat, Faculty of Commerce and Accountancy, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand. Emaila ddress: tanakorn@cbs.chula.ac.th

Article history: Received: 13-03-2014 Revised:30-04-2014 Accepted: 16-07-2014

ABSTRACT

The purposes of this study were to classify university students in terms of their materialism and to compare the difference in certain attributes among the segments. Student attributes taken into consideration included father's educational level and occupation, money received from family, family communication and susceptibility to peer influence. In this survey research, questionnaires were used to collect data from 620 students ranging from 18 to 21 years old in Bangkok. Cluster analysis was used where students could be classified into three clusters: those who believe that money is the center of life (centrality); those who believe that money is a measure of success in life (success); and those who believe that money makes a happy life (happiness). Students from the three clusters appeared to be of different attributes. Those in the centrality group are from poorer family while those in the success cluster are from a family with better financial status, and those in the happiness cluster are more susceptible to peer influence than the other two groups. The implications of the study were discussed as a concluding remark.

Key words: materialism; family communication; susceptibility to peer influence.

RESUMEN

Los objetivos de este estudio fueron clasificar a los estudiantes universitarios en términos de su materialismo y comparar la diferencia en ciertos atributos entre los segmentos. Los atributos que fueron tomados en consideración fueron: el nivel educativo y ocupación del padre, el dinero recibido de la familia, la comunicación familiar y la susceptibilidad a la influencia de los pares. En esta investigación fueron utilizados cuestionarios para recopilar datos de 620 estudiantes entre 18 y 21 años de edad en Bangkok. Se utilizó el análisis de conglomerados donde los estudiantes podían clasificarse en tres grupos: los que creen que el dinero es el centro de la vida (centralidad), los que creen que el dinero es una medida del éxito en la vida (éxito), y los que creen que el dinero hace una vida feliz (la felicidad). Los estudiantes de los tres grupos parecían ser de diferentes atributos. Los estudiantes del grupo de centralidad provienen de familias más pobres, mientras que aquellos en el grupo de éxito provienen de familias con una mejor situación financiera, finalmente los del colectivo de felicidad son más susceptibles a la influencia de los pares que los otros dos grupos. Las implicaciones del estudio fueron discutidas como un comentario final.

Palabras clave: materialismo, comunicación familiar, susceptibilidad a la influencia de los pares.

1. INTRODUCTION

Materialism is viewed as a personal value that is reflected by people's beliefs about the importance that possessions play in their lives (Richins, 2011). Materialistic individuals value acquisitions and the display of their acquired assets (Roberts, 2011). Owning the right possessions is a key to happiness and the success is judged by the things they own (Richins, 2011). Consequences of materialism have been revealed by many educators in terms of happiness and well-being. Firstly, people place more importance on products over experience (Van Boven & Gilovich, 2003). A great portion of time and energy is dedicated to acquiring, possessing and thinking about material things (Roberts, 2011). Life for them is about striving, about reaching for those which they desire (Sheldon & Kasser, 2008). Secondly, materialistic individuals usually have poor interpersonal relationship with other people and selfish behavior (Kasser, 2005). They care more about themselves than other people including family members or religion (Burroughs & Rindfleisch, 2011). Lastly, materialistic values can cause a variety of many mental health problems such as anxiety and depression; hence, theyit worsens quality of life (Schor, 2004). People with materialistic inclination are more concerned about tangible objects than intangible feelings or ideas. They can be driven to have more and more money or possessions to the extent where they neglect to consider their emotional well-being. The assets they gain do not give them the pleasure in life or enhance their subjective well-being (Richins & Dawson, 1992; Van Boven, 2005). The more materialistic they are, the less satisfied and happy they become.

Despite that fact, the number of materialistic teenagers is increasing. Most teenagers have set making a lot of money one of their future goals (Schor, 2004). This materialistic inclination is driven in part by advertising which in turn leads to overconsumption of products and services (Pratkanis, 2007; Vega & Roberts, 2011). According to La Ferle and Chan (2008), children and teenagers are the main target groups of marketers as they can more readily make purchase decisions than other groups of consumers. Materialistic values in teenagers affect the balance between their private life and the level of sacrifice they are willing to make for the public (Goldberg et al, 2003). Teenagers with materialistic values have decreased subjective well-being as they would be comparing their riches, possessions, social statuses and images with those of others. As Chaplin and John (2007) put up, insecurity is a key factor in the formation of material values in teenagers. When they have no material possessions that their peers have, they experience this deficit acutely (Pugh, 2009). They feel they need to compete with those people.

The process where teenagers are trained, educated and implanted with consumption-oriented attitudes is called consumer socialization (Lueg & Finney, 2007). They come to know the consumption behaviors through socializing agents such as parents, peers, schools, stores, media, products and even packages (Moschis et al., 2011). Parents are the most important role models (Banerjee & Dittmar, 2008; Roberts, Manolis, & Tanner, 2008) who show teenagers what reasonable consumption is like (Chaplin & John, 2010). They are the ones who teach the children how to consider the relativity between price and quality, how to spend wisely, and how to study information relevant to the products before making that purchase decision (Bindah & Othman, 2011; Chan & Prendergast, 2007).

Several studies have found that the family environment is crucial to the development of materialistic values and parents' stance of upbringing and treatment of children where their needs are not satisfied are the causes of materialistic values (Chang et al, 2008;Moschis, Hosie, &Vel, 2009; Moschis et al, 2011). That is, children raised in socio-oriented communication environment where unity among family members is emphasized and contradiction avoided can become highly materialistic once they are grown up. On the other hand, children raised in a family with concept-oriented communication patterns where free speech is valued grow up to become adults who are less materialistic. The study of Chan and Prendergast (2007) in Hong Kong families suggests otherwise. The findings reveal that both concept-oriented communication and socio-oriented communication do not have any impact on materialism. Hong Kong teenagers hardly consult family members when in need of information to support their product purchase decisions.

In addition, peer is another factor which should be taken into account in the present study. The behavior of teenagers which is in line with friends and with an intention to gain acceptance from them is deemed important. The more susceptible teenagers are to peer influence, the more they will compare their possessions with those of their friends and the more materialistic they will become (Moschis et al, 2011). According to Mangleburg, Doney, and Bristol (2004), in a consumer context, teenagers usually request friends to help evaluate products, brands, and stores in ways that enhance a sense of belonging, causing teens to form an identity separate from parents. For example, shopping with friends may help assure that they get create favorable images among their friends. Peer groups may reward "appropriate" purchases with enhanced standing in the group. Susceptibility to peer influence, then, may help teens to construct desirable social identities. Nguyen, Moschis, and Shannon (2009) studied a sample group of Thai students in Bangkok and found the peer discussions on consumption of products to be positively related to materialistic value. This finding is consistent with other studies which find teenagers who are in frequent contact with friends and susceptible to peer influence to be highly materialistic (Bindah & Othman, 2012;Chan & Zhang, 2007) and susceptibility to peer influence (Banerjee & Dittmar, 2008;Roberts, Manolis, & Tanner, 2008). Therefore, it can be said that the important factors creating materialistic value in teenagers are parents and friends. We, therefore, conceptualize teens' materialistic values and behaviors in this study by the function of how they are influenced by friends.

Socioeconomic status is one factor that should be focused since it may affect a person's materialistic value. Insecurity in life is seen as a cause of materialism (Kasser et al, 2004) That is, people from poorer families, who are deprived of the opportunity plan for the future of themselves and family members, feel insecure about their life so they accord more importance to possessions and money than people from families with higher education and better financial status. Moreover, people who feel inadequate in terms of personal and professional competencies try to compensate insecurity with a high-status automobile (Rucker & Galinsky, 2008; Sivanathan & Pettit, 2010). Chan and Cai (2009) found that individuals growing up in families where the parents lack financial stability would become more materialistic than those who are from families where the parents are more financially secure. Additionally, the study of Flouri (2004) revealed that teenagers from poorer socioeconomic status with parents who are not as well educated or engaged in labor work and with a lower income are more materialistic than teenagers from families with better socioeconomic status.

In undertaking studies on materialistic values in teenagers, the issue of cultures should be taken into consideration. Cultures may differ on the extent to which material goods and services are emphasized (Shrum et al., 2012). According to Moschis et al (2011), Western cultures tend to exhibit individualistic values where material symbols are seen as an indicator of success. In contrast, Eastern cultures hold collectivistic values and thus devalue material possessions (Wong, Rindfleisch, & Burroughs, 2003). Thailand is a collective society where children are taught to respect and be obedient to adults. These cultures define the contexts in which Thai teenagers have been raised and taught.

Since the majority of researches on materialism were conducted in the Western cultures, it is interesting to investigate the development of materialistic values among teenagers in Eastern cultures, especially in countries such as Thailand. The materialism in the current study was focused on various perspectives including social, cultural, psychological and economic as suggested by Bindah and Othman (2011). The objectives of this research, therefore, are to study how teenagers value possessions and money and to see how teenagers from families with different socioeconomic statuses value possessions and money.

2. METHOD

2.1 Participants

The population in this study was undergraduate students at private and public universities in Bangkok, Thailand. The combined number of undergraduate students at these 29 institutions was 424,660 (Office of the Higher Education Commission, Thailand, 2010). The appropriate sample group, as determined by quantitative variables with known population size (Cooper & Sclindler, 2001), was 650 students. The sample was randomly selected from two private universities and four public universities. Research assistants were then asked to collect data from the students at the six institutions using 650 copies of a self-report questionnaire. After the questionnaires had been returned, the research assistants found 620 copies to be complete and 30 copies to be incomplete. The valid response rate was at 95.3%.

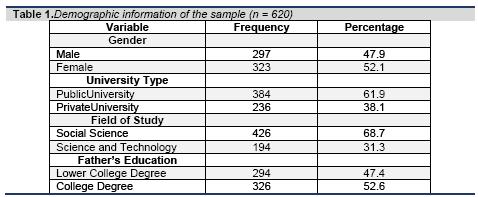

There were slightly more female (52.1%) than male students (47.9%). The age range of participants was between 18 and 21. Among this sample group, 52.6% of the students had a father who held a college degree while the fathers of 47.4% of the students held a lower degree than that. When father's occupation was analyzed for occupational prestige, the lowest score was 32.0 (i.e. employee) while the highest was 78.7 (i.e. medical doctor), with an average at 52.2 (i.e. entrepreneur). Parents' occupational status indicated that the sample population was predominantly of middle to upper-middle class of socioeconomic background. Details of the demographic features of the sample are presented in Table 1.

2.2 Instruments

There were four main parts of the questionnaire. The first one acquired the respondents' personal information including gender, university type, field of study, father's educational level, father's occupation, and money received from the family. "Father's educational level" was measured from the number of years spent by the father in the education system. The score was given by the number of years in school or college attended. For example, a father who finished Grade 6 would be given a score of 6 while a father who held a doctoral degree would be given a score of 20. "Father's occupation" was scored by referring the occupation of their father as indicated by the students against the occupational prestige criteria of Chantavanich (1991). "Money received from family" was the disposable income students received from their parents or guardians for a month.

The second part of this questionnaire was the materialism scale developed from the Richins and Dawson's Materialism Scale (Richins & Dawson, 1992). While the original scale template contained eighteen question items, this study used only fifteen in order to fit in with the context of the Thai society. Questions were, for instance, "I admire people who own expensive homes, cars, and clothes"; and "It sometimes bothers me quite a bit that I can't afford to buy all the things I like." The Materialism scale used here was in 5-point Likert response format, anchored with strongly disagree and strongly agree.

The third part was family communication scale which followed the template of the concept-oriented family communication about consumption of Moschis, Moore and Smith (1984). The five questions were "My parents say that buying things I like is important even if others do not like them"; "My parents let me decide how I should spend my money"; "My parents ask me what I think about the things I buy for myself"; "My parents think that I can decide which things I should or shouldn't buy"; and "My parents ask me for advice when buying things for the family." Similarly, the response was in 5-point Likert format where the respondents were asked to indicate their opinion on the scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree.

Lastly, susceptibility to peer influence scale was from the scale of Mangleburg and Bristol (1998).The six questions to determine the opinion of the students on peer influence were "If I don't have a lot of experience with a product, I often ask my friends about it"; "I usually ask my friends to help me choose the best product"; " I look at what my friends are buying and using before I buy"; "it is important that my friends like the products and brand I buy"; "I only buy those products and brands that my friends will approve of"; and "I like to know what products and brands make a good impression on my friends." The response was in 5-point Likert scale.

Then the three parts of the questionnaire obtained from the sample wereas examined for reliability. The inter-item reliability (Cronbach's alpha) of materialism scale, family communication scale, and susceptibility to peer influence scale was 0.87, 0.83, and 0.76 respectively.

2.3 Procedure

The statistical analysis procedures employed in this study were descriptive statistics, exploratory factor analysis, cluster analysis and a one-way ANOVA. Firstly, descriptive statistics, such as simple frequencies and mean value, were computed on the socio-demographic. Next, a principle component factor analysis with varimax rotation was conducted to classify students by their attitude towards material possessions. A reliability analysis, using Cronbach's alpha, was undertaken to test the reliability of each of the materialism factors. In addition, a cluster analysis was subsequently conducted using three identified materialism factors to segment students. K-means clustering method was performed, and the 3-cluster solution was determined to be the most appropriate mean to understand the attitudinal difference among students. Lastly, One-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was used to test the mean difference of variables across materialism segments. The calculations were performed with SPSS program, version 19.0.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Factor analysis of materialistic values

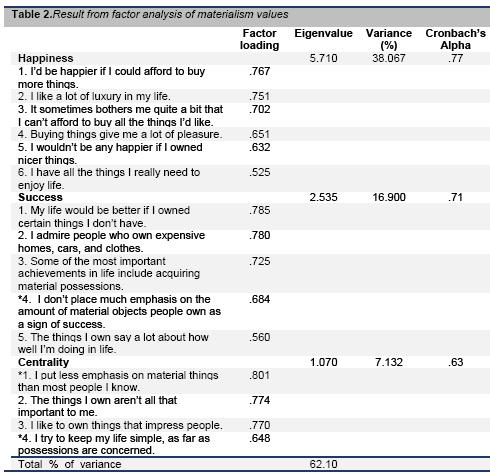

Responses to the fifteen question items on the materialism scale were used to classify the students by their attitude and the level of significance they accorded to material possessions. Exploratory Factor Analysis with varimax rotation was conducted. In this process, the minimum Eigen value of 1.0 was used as cut-off. For each student attitude scheme, only the constituent statements with factor loadings of more than .60 were retained. The results indicated that the selected items could be assigned to three factors (see Table 2). The value for the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) criterion was 0.906 which was higher than 0.8, suggesting that the data was suitable for Factor Analysis (Hair et al, Anderson, Tatham, & Black, 2005 and the explained variance was 0.621. The Cronbach's Alpha ranged from 0.63 to 0.77, which surpassed the criteria for reliability acceptability (Nunnally, 1978). The three identified factors "Happiness", "Success" and "Centrality" were labeled.

3.2 Cluster analysis for value segmentation of respondents

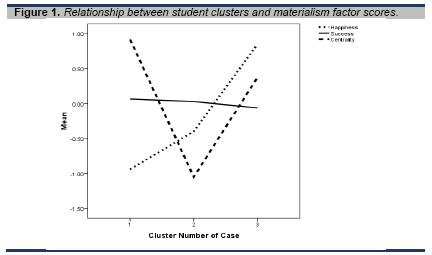

The data analysis part was intended to segment the students on the basis of their materialistic values. Cluster analysis was used with factor scores derived as a variable for this segmentation. The results of the analysis showed what the main reason was for each student's belief in the significance of possessions or money. The students were classified into three clusters of materialism with a graph depicting the relationship between these student clusters and the factor scores as shown in Figure 1.

From Figure 1, the horizontal axis (X-axis) represented students' clusters while the vertical axis (Y-axis) represented materialism factor scores. The first cluster of students had a high centrality score. The second cluster of students had a high success score. The third cluster of students had a high happiness score. The groups, therefore, were given labels as follows:

Group 1 - Centrality: Students who valued possessions and money because they believed them to be the center of their life. Their goal in life was to have significant amount of possessions or money.

Group 2 - Success: Students who valued possessions and money because they believed them to be the indicators of a person's success in life.

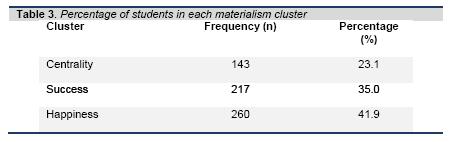

Group 3 - Happiness: Students who valued possessions and money because they believed them to be the elements bringing happiness in life. The sample group of 620 students could be classified into the three clusters as presented in Table 3.

As you can see from Table 3, the largest cluster is happiness (41.9%), followed by success (35%) and centrality (23.1%). In other words, most students value possessions and money because they believe happiness can be achieved through these elements.

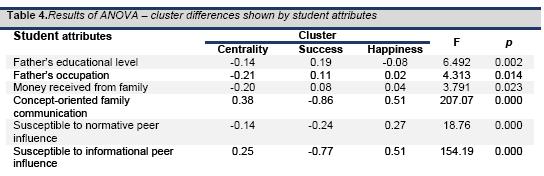

Cluster differences toward materialism values The three clusters were compared to determine the particular differences in familial variables which included father's education, father's occupation, money received from the family, family communication and susceptibility to peer influence. One-way ANOVA was used to analyze the data. The researcher transformed the data value of these variables into standard scores in order to adjust the data to a normal distribution. By so doing, all variables applied the same measuring unit for ease of interpretation. Analysis results can be found in Table 4.

From Table 4, it can be noticed that students from different clusters had statistically significant differences in the mean scores of all attributes. The differences can be described by the clusters as follows:

- Centrality cluster: Students were from families with lower father's education level than the other clusters. Fathers in these families were engaged in occupation with lower occupational prestige than the other clusters. Students received less money from the family. Family communication was one where the parents gave their children the freedom to make purchase decisions on their own.

- Success cluster: Students were from families with higher father's education level. Fathers in these families were engaged in occupation with higher occupational prestige. Family communication was highly regulated by the parents. Students were not given much freedom to make decisions. The students themselves were not susceptible to peer influence.

- Happiness cluster: Students were from families of moderate financial status. Fathers in these families were engaged in occupation with moderate occupational prestige. Family communication was one where the freedom to make decisions was given by the parents. Students were more susceptible to peer influence than the other two clusters.

4. DISCUSSION

Teenagers have become more materialistic these days, believing that they possessions can bring happiness and that they are indicators of success in life. Their lifestyle has material possessions in a central position. It is necessary to find out how undergraduate students from families with different social circumstances value material possessions since the findings can be used to develop a guideline that helps curb their materialism. When students in each cluster were compared to see how they are different in terms of family background, the findings suggested several issues.

Firstly, students in the centrality cluster believe that possessions and money are the center of life. This is probably because they are mostly from a poorer family than students in the other clusters. Fathers have lower education and less prestigious occupation. Money received from the family is less than that in the other clusters as well, but their parents do give them the freedom to make decisions. The finding can be explained by the statement of Richins (2011) in that teenagers use possessions to express who they are. The less they are not rich, the more they are material-oriented. So, they accord more importance to possessions and money than those people from families with higher education and better financial status. The family environment is crucial to the development of materialistic values, and parents' stances of upbringing and treatment of children where their needs are not satisfied are the causes of materialistic values (Chaplin & John, 2007). This finding of this research is consistent with the previous study which found that individuals growing up in families where the parents are financially insecure will become more materialistic (Chan & Cai Zhang, 2007).

Moreover, students in the centrality cluster might imitate their parents, obsessed with possessions and money. Parents are the role models who show children what reasonable consumption is like (Banerjee & Dittmar, 2008;Roberts, Manolis, & Tanner, 2008). Apart from that they fail to teach the children how to consider the relativity between price and quality, how to spend wisely, and how to study information relevant to the products before making that purchase decision. The center of their life or their goal, therefore, is to accumulate as much as possible as a security for the future. So, it is rather dangerous when this group has to stay in a place where lots of rich people are around. For instance, when they study in a private university where most of their peers have power to buy things. They feel they need to compete with their peers. The more susceptible teenagers are to peer influence, the more they compare their possessions with those of their friends and the more materialistic they become (Moschis et al, 2011). It is also noted that centrality group has more susceptible to informational peer influence than to normative peer influence. This means, students in this group tend to listen to peers or accept the information from peers. However, they cannot yield to the needs of their friends such as buying the brand to be admired by the group because of financial obstacles.

Secondly, students in the success cluster who believe that possessions and money are indicators of success in life are mostly from a family with better financial status than students in the other clusters. This might be because their fathers have higher education and more prestigious occupation. However, the parents are controlling and do not offer much freedom to the children to make decisions on their own. Therefore, these students are not susceptible to peer influence. They see their parents as models and try to follow the same route. This circumstance can be explained with using the Social Learning Theory (Bandura, 1977) which proposes that people develop their own behaviors and attitudes by observing the behaviors and attitudes of people with significance in their lives. This process of learning through observing others is called modeling. In other words, students in this success cluster have observed their father, a person who is close to them. Their father is a successful individual who commands the respect of the society, and as such they accord significance to success in life as their father does. They pay more attention to their parents' suggestion than peers. The results are found to be in accordance with what Moschis et al (2011) state in that when teenagers are less susceptible to peer influence, they will become less materialistic. We may conclude that teenagers who come from rich family are not influenced by peers to value materialism. Therefore, they tend to be more successful than others since they listen to parents. The results can be used to support the concept that family communication is an essential element in the conditioning of teenagers (Bindah & Othman, 2011).

The last finding reveals that students in the happiness cluster are more are the group with higher susceptibleility to peer influence than the other two groups. One of the reasons is probably because they come from a family with moderate financial status. Their parents give them the freedom to make decisions. Since they are not success-oriented, they have an easy lifestyle without stress. Free time is mostly spent with their friends. According to Moschis et al (2011), the more susceptible teenagers are to peer influence, the more they will compare their possessions with those of their friends and the more materialistic they will become. So, this group tends to value materialism and possess materialistic behavior. This finding is consistent with previous studies which find teenagers who are in frequent contact with friends and susceptible to peer influence to be highly materialistic (Bindah & Othman, 2012; Chan & Zhang, 2007; Roberts, Manolis, & Tanner, 2008).

5. CONCLUSION

This article examines how teenagers from families with different socioeconomic statuses value possessions and money. Some implications are presented based on the findings as follows. First of all, since teenagers who are of high materialistic values may be experiencing reduced well-being because their needs are not satisfied, it will be useful if their parents notice certain behaviors such as negative interaction, depression, or anxiety which might occur so that they can help solve the problems immediately. In addition, we raise more awareness of how teenagers develop their materialistic values. Teenagers who communicate more frequently with peers about consumption matters are likely to develop more materialistic values. That is, having peers with higher social status can lead to inappropriate purchases. Consumption is just a way to stand in the group. These problems make us realize the significance of family communication. Teenagers should be taught by parents who can provide them with rational aspects of consumption and how to choose the right friends. Lastly, to curb materialism, creating a new value is deemed important in Thai culture. That is, teenaged students should be taught that material possessions are not the only valid indicators. Success in life can be gauged from the good deed and the contribution people make to the society.

6. REFERENCES

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

Banerjee, R., & Dittmar, H. (2008). Individual differences in children's materialism: The role of peer relations. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34, 17-31. [ Links ]

Bindah, E.V., & Othman, M. N. (2011). The role of family communication and television viewing in the development of materialistic values among young adults. A Review of International Journal of Business and Social Science, 2(3), 238-248. [ Links ]

Bindah, E.V., & Othman, M. N. (2012). An empirical study of the relationship between young adults consumers characterized by religiously-oriented family communication environment and materialism. Cross Culture Communication, 8(1), 7-18. [ Links ]

Burroughs, J. E., & Rindfleisch, A. (2011). What welfare? On the definition and domain of consumer research and the foundational role of materialism. In D. G. Mick, S. Pettigrew, C. Pechmann, & J. L. Ozanne (Eds.), Transformative consumer research for personal and collective well-being (pp. 249-266). New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Chan, K., & Cai, X. (2009). Influence of television advertising on adolescents in China: An urban-rural comparison. Young Consumers, 10(2), 133-145. [ Links ]

Chan, K., & Prendergast, G. (2007). Materialism and social comparison among adolescents. Social Behavior and Personality: an International Journal,35(2), 213-228. [ Links ]

Chan, K., & Zhang, C. (2007). Living in a celebrity-mediated social world: the Chinese experience. Young Consumers,8(2), 139-152. [ Links ]

Chang, W. L., Liu, H. T., Lin, T. A., & Wen, Y. S. (2008). Influence of family communication structure and vanity trait on consumption behavior: A case study of adolescent students in Taiwan. Journal of Adolescence, 43, 417-435. [ Links ]

Chantavanich, S. (1991). Social stratification: Occupational prestige in Thai society. (Research Report). Bangkok: Chulalongkorn University Social Research Institute. [ Links ]

Chaplin, L. N., John, D. R. (2007). Growing up in a material world: Age differences in materialism in children and adolescents. Journal of Consumer Research, 32, 119-129. [ Links ]

Chaplin, L. N., & John, D. R. (2010). Interpersonal influences on adolescent materialism: A new look at the role of parents and peers. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 20, 176-184. [ Links ]

Cooper, D. R., & Sclindler, P. S. (2001). Business research methods, (7th ed.). Singapore: Mc Grow-Hill. [ Links ]

Flouri, E. (2004). An integrated model of consumer materialism: Can economic socialization and maternal value predict materialistic attitudes in adolescents? Journal of Socio-Economics, 28, 707-724. [ Links ]

Goldberg, M. E., Gorn, G. J., Peracchio, L. A., & Bomossy, G. (2003). Materialism among youth. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 13(3), 278-288. [ Links ]

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., Babin, B., & Black, W. C. (2005). Multivariate data analysis (5th ed.). New Jersey: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Kasser, T. (2005). "Frugality, Generosity, and Materialism in Children and Adolescents," in What Do Children Need to Flourish? Conceptualizing and Measuring Indicators of Positive Development, Kristin Anderson Moore and Laura H. Lippman, eds, New York: Springer Science, 357-373. [ Links ]

Kasser, T., Ryan, R. M., Couchman, C. E., & Sheldon, K. M. (2004). Materialistic values: Their causes and consequences. Psychology and consumer culture. Washington, DC: American Psychology Association. [ Links ]

La Ferle, C., & Chan, K. (2008). Determinants for materialism among adolescents in Singapore. Journal of Young Consumer, 9(3), 201-214. [ Links ]

Lueg, J. E., & Finney, R. Z. (2007). Interpersonal communication in the consumer socialization process: scale development and validation. Journal of Marketing Theory & Practice, 15(1), 25-39. [ Links ]

Mangleburg, T. F., & Bristol, T. (1998). Socialization and adolescents' skepticism toward advertising. Journal of Advertising, 27(3), 11 -21. [ Links ]

Mangleburg, T. F., Doney, P., & Bristol, T. (2004). Shopping with friends and teens' susceptibility to peer influence. Journal of Retailing, 80, 201 -216. [ Links ]

Moschis, G. P. (2007). Stress and consumer behavior. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 35(3), 430-444. [ Links ]

Moschis, G. P., Hosie, P., & Vel, P. (2009). Effects of family structure and socialization on materialism: A life course study in Malaysia. Journal of Business and Behavioral Sciences, 21(1), 166-181. [ Links ]

Moschis, G. P., Moore, R. L., & Smith, R. B. (1984). The impact of family communication on adolescent consumer socialization. In T, Kinnear (Ed.), Advances in Consumer Research, 11, 314-319. [ Links ]

Moschis, G. P., Ong, F. S., Mathur, A., Yamashita, T., & Benmoyal-Bouzaglo, S. (2011). Family and television influences on materialism: A cross-cultural life-course approach. Journal of Asia Business Studies, 5(2), 124-144. [ Links ]

Nguyen, H. V., Moschis, G. P., & Shannon, R. (2009). Effects of family structure and socialization on materialism: a life course study in Thailand. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 33, 486-495. [ Links ]

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory. New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Office of the Higher Education Commission, Thailand. (2010). Educational information, Ministry of Education. Retrieved April, 28, 2012, from http://www.moe.go.th/data stat/. [ Links ]

Pratkanis, A. R. (Eds.). (2007). The science of social influence: advances and future progress. Frontiers of Social Psychology. Philadelphia, PA: Psychology Press. [ Links ]

Pugh, A. (2009). Longing and belonging: Parents, children, and consumer culture. Berkeley: University of California Press. [ Links ]

Richins, M. L. (2011). Materialism, transformation, expectation, and spending: Implication for credit use. Journal of Public Policy and Marketing, 30(2), 141-156. [ Links ]

Richins, M. L., & Dawson, S. (1992). A consumer value orientation for materialism and its measurement: Scale development and validation. Journal of Consumer Research, 19, 303-316. [ Links ]

Roberts, J. (2011). Shiny Objects: Why we spend money we don't have in search of happiness we can't buy. New York: Harper Collins. [ Links ]

Roberts, J. A., Manolis, C., & Tanner, J. (2008). Interpersonal influence and adolescent materialism and compulsive buying. Social Influence, 3, 114-131. [ Links ]

Rucker, D., & Galinsky, A. (2008). Desire to acquire: Powerlessness and compensatory consumption. Journal of Consumer Research, 25, 257-267. [ Links ]

Schor, J. B. (2004). Born to buy: The commercialized child and the new consumer culture. New York: Scribner. [ Links ]

Sheldon, K., & Kraser, T. (2008). Psychological threat and extrinsic goal striving. Motivation and Emotion, 32 (1), 37-45. [ Links ]

Shrum, L. J., Wong, N., Arif, F., Chugani, S. K., Gunz, A., Lowrey, T. M., Nairn, A., Pandelaere, M., Ross, S. M., Ruvio, A., Scott, K., & Sundie, J. (2012). Re-conceptualizing materialism as identity goal pursuits: Functions, processes, and consequences. Journal of Business Research, 66(8), 1179-1185. [ Links ]

Sivanathan, N., & Pettit, N. (2010). Protecting the self through consumption: Status goods as affirmational commodities. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46(3), 564-570. [ Links ]

Van Boven, L. (2005). Experientialism, materialism, and the pursuit of happiness. Review of General Psychology, 9(2), 132-142. [ Links ]

Van Boven, L., & Gilovich, T. (2003). To do or to have? That is the question. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(6), 1193-1202. [ Links ]

Vega, V., and Roberts, D. (2011). The Role of Television and Advertising in Stimulating Materialism in Children. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the International Communication Association, New York, Retrieved May, 8, 2012, from http://www.allacademic.com/meta/p13169_ind ex.html. [ Links ]

Wong, N., Rindfleisch, A., & Burroughs, J. (2003). Do reverse-worded items confound measures in cross-cultural consumer behavior? The case of material value scale. Journal of Consumer Research, 30(2), 72-91. [ Links ]