Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

International Journal of Psychological Research

Print version ISSN 2011-2084

int.j.psychol.res. vol.8 no.2 Medellín July/Dec. 2015

Supporting protest movements: The effect of the legitimacy of the claims

Apoyo a los movimientos de protesta: El efecto de la legitimidad de los reclamos

Stefano Passinia,* and Davide Morsellib

a Department of Education Studies, Università di Bologna, Bologna, Italy.

b Interdisciplinary institute for the study of life trajectories ITB, Université de Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland.

* Correspondence: Stefano Passini, Department of Educational Science, Università di Bologna. Address: Via Filippo Re, 6 – 40126 – Bologna (Italy) Bologna, Italy. Phone: +39.051.2091622, E mail: s.passini@unibo.it

Article history: Received: 10-12-2014 Revised: 29-04-2015 Accepted: 20-05-2015

ABSTRACT

Past research has investigated the motivations behind support to protest actions by mainly focusing on the relationship between the perceptions of protest movements and support itself. The aim of the present research is to extend this research also by considering the qualitative content of the claims advanced by the protesters. We analyzed whether supporting a protest depends on the legitimacy of the advanced claim (i.e. in terms of adherence to democratic principles) or on the legitimacy attributed to that group. One hundred and eighty Italian citizens (45.9 % women; M age = 41.64, SD = 13.69) responded to an online questionnaire concerning a protest movement. The design included 2×2 conditions: non-threatening vs. threatening type of group and unbound vs. restricted protesters' claims. The results showed that support given to the protest is overlooked when the group is perceived as more threatening. However, the perception of the protest group has no effect on value-oriented participants who instead focus on the claims.

Key words: Legitimacy; protest; democracy; threat; value-oriented citizenship.

RESUMEN

Estudios previos han investigado las motivaciones detrás del apoyo a las acciones de protesta, centrándose principalmente en la relación entre la percepción de los movimientos de protesta y lo apoyo. El objetivo del presente trabajo fue extender esta investigación, considerando también el contenido cualitativo de las reclamaciones presentadas por los manifestantes. Se analizó si el apoyo a una protesta depende de la legitimidad de la reclamación avanzada (en términos de adhesión a los principios democráticos) o en la legitimidad atribuida a ese grupo. Ciento chenta ciudadanos italianos (45.9% mujeres; edad M = 41.64, SD = 13.69) respondieron a un cuestionario online relativo a un movimiento de protesta. El diseño incluye 2 × 2 condiciones: tipo de grupo no amenazantes vs. amenazantes y reclamación avanzada dilatada vs. restringida. Los resultados mostraron que el apoyo a la protesta se descuida cuando el grupo se percibe como más amenazante. Sin embargo, la percepción del grupo de protesta no tuvo ningún efecto sobre los participantes orientados a los valores a que en su lugar se centraron en las reclamaciones.

Palabras clave: Legitimidad; protesta; democracia; amenaza; orientación hacia los valores.

1. INTRODUCTION

Joining different types of protest (from signing petitions to participating in action movements) has become a socially acceptable and common behavior in Western countries (Norris, 2002). The panorama is largely heterogeneous: e.g. from the Tea Party movement (a conservative political movement which emerged in 2009 in the United States) to the Iran Human Rights (an international non-profit organization founded in 2007 that promotes campaigns against the death penalty). Political and social psychological research has shown that these protests either become relevant or disappear depending on the support they receive from the population at large (see Klein, Spears & Reicher, 2007; Mugny, 1982; Mugny & Pérez, 1991; Passini & Morselli, 2013; Rucht, 2004; Simon & Klandermans, 2001; Thomas & Louis, 2014). Indeed, a protest group needs support to emerge and bring about change. That is, social movements have little direct impact on policies (Giugni, 1999). Instead, they have indirect influence via public opinion: i.e. movements and groups influence public opinion which in turn has some influence on political decision-making. Thus, public opinion becomes crucial for protest groups: failing to have the support of public opinion undermines their major source of influence on policy.

If the support from the population is essential for protest success, then some questions arise: why do people support protest in some cases and not in others? What elements do people consider in deciding whether to join a cause? These issues are indeed relevant not only for the study of political activism - i.e. how and why people engage in protests - but also for understanding why some protest movements receive support and others do not.

Many scholars of social psychology have investigated the motivations behind the decision as to whether or not to join protest actions. These studies have mainly linked such motivations to models of frustration-aggression and relative deprivation (see Smith, Pettigrew, Pippin & Bialosiewicz, 2012), models focused on the perceived costs and benefits of participation (see Kelly & Breinlinger, 1996), theories of system justification (see Jost et al., 2012), and theories of social identity and social identification (see Klandermans, 2002; Simon & Klandermans, 2001; Stewart et al., 2015; van Zomeren, Postmes, et al., 2008). Some inadequacies of the first two approaches have been already highlighted (Kelly & Breinlinger, 1996; Klandermans & Oegema, 1987; Simon et al., 1998). In particular, concerning third-party support the cost-benefit approach fails to explain why sometimes people support movements that may prove to be costly (i.e. in terms of personal time, money, and risks) and from which they do not get any rational benefit even in case of success (e.g. movements for the rights of Amazonian tribes).

Alternatively, the application of social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1979) to the study of movements suggests that support to protest groups is predicted by perceived closeness to that group (e.g. workers' rights of one's own same category), by social identification with that group, and by not perceiving it to be threatening or in competition with the ingroup (see Klandermans, 2002). Indeed, threat increases the negative perception of the threatening group and prejudices against this group (e.g. Meeus, Duriez, Vanbeselaere, Phalet & Kuppens, 2009). Thus, this approach mainly focuses on the perception of the protest group (i.e. the claimant) by potential supporters and on its influence on the decision to back it. Indeed, recent models explaining protest support considers identification with a social movement as the main predictor of collective action (see van Zomeren, Postmes & Spears, 2012). But does this effect just depend on the identification with the group regardless of the claim advanced or do people consider the legitimacy of the protest group's demands in terms of fairness and adherence to more general democratic principles and values? Indeed, not all protest movements ask for an improvement in such principles. In this sense, in studying individual support for protest, it is relevant not only to consider the identification with protest groups, but also to focus on which type of social change these groups propose. Indeed, history teaches us that people often supported protest movements even when they did not propose a real change in the social conditions or they restructured inequalities among social groups instead of overcoming them. For instance, in the 1969 Libyan revolution, the groups that opposed unequal policies of the governing political regime, once they had taken over power, did not enhance social equality for all the social groups but rather structured another system in which one group dominated over the others, without producing a truly structural change (Bruce St John, 2008).

An interesting analysis which considers the perception of the content of the claim and not just identification with the claimant is Kelman and Hamilton's (1989) theory on legitimacy. Kelman (2001, p. 55, original italics) defined legitimacy as "an issue that arises in an interaction or relationship between two individuals, or between one or more individuals and a group, organization or larger social system, in which one party makes a certain claim, which the other may accept or reject. Acceptance or rejection depends on whether that claim is seen as just or rightful." According to the author, legitimacy can be indeed evaluated at least on two levels: the first concerns the legitimacy of the claim itself; the second concerns the legitimacy of the claimant, i.e. the person, group, or larger social system that makes the claim.

Kelman and Hamilton (1989) used these two levels to study the influence that the authority has on the subordinates. Indeed, group members obey the authority to the extent that they perceive its legitimacy. However, the two authors show that people mainly tend to judge authority's demands just focusing on the evaluation of authority's legitimacy. That is, few people focus on the legitimacy of the claim, while the majority focuses on the legitimacy of the authority. Instead, when the authority issues a request, the evaluation of the legitimacy of the request - rather than of the authority - becomes crucial in judging the fairness of a demand in terms of justice and equality. The relevant point in Kelman and Hamilton's theory is the consideration of individual differences in evaluating legitimacy. Indeed, which people focus on the legitimacy of the claim and which on the claimant? To answer to this question, Kelman and Hamilton distinguished between three orientations of citizens (rule-, role-, or value-oriented) described as different ways of conceptualizing and relating to issues with a political relevance, such as policy making. Rule-oriented citizens are keener to follow rules without questioning the legitimacy of the claim. Similarly, role-oriented citizens elaborate judgements on the basis of their role obligations, yet not questioning the claims itself if it remains within their obligations. On the contrary, value-oriented citizens base their judgement on universal values of justice and equality and thus are more likely to evaluate policies (Kelman & Hamilton, 1989; see also Passini & Morselli, 2011).

According to this model, the citizens' political orientation does not affect per se the response to a legitimate authority's claim. However, when a legitimate authority issues an illegitimate claim, value-oriented citizens are the most likely to oppose the authority against that specific claim. This effect was observed in a series of experimental designs that showed that in general people bypassed the evaluation of the specific claim (e.g. violation of basic human rights) and accept the claim when it was issued by authorities that they considered as legitimate (e.g. democratic authority, see Passini & Morselli, 2010. However, the citizens who based their political orientation on values were readier to disobey the authority's claim than the others.

If these two levels of legitimacy (claimant and claim) were used in the analysis of the individual-authority relationship, it may be useful to apply the same model to study the influence that a protest movement has on people's support. Framing the perception of legitimacy of disobedient groups and their claims may indeed improve the understanding of the dynamics behind the decision as to whether to support movements and to join a protest. For what concerns the legitimacy of the claimant (i.e. the group that makes the claim), this may be analyzed as the people's representation of that group in relation to the society in which they live. That is, how much people consider that particular group to be in accordance with the established rules, principles, and values of their society. Moscovici and Pérez (2007) have shown that shared and common representations of minorities affect the way those minorities are approved or disapproved of by the authority and the population. In their study on the representations of Gypsy persecution in Europe, this minority was more likely to be accepted and supported by people when public opinion depicts Gypsies as less threatening. These considerations are not far from postulates in the approach of social identity theory, according to which intergroup dynamics (ingroup vs. outgroup) and the perception of the other's threat play important role in supporting protest movements. Thus, in our model of protest groups' legitimacy, we decided to focus on threat as relevant in evaluating the legitimacy of these groups. Thus, whether people evaluate legitimate or illegitimate the other groups in terms of the threat they pose to society's values.

However, this is only one part of the story, and not much is said about the reception of the claims that protest groups advance, independently from the legitimacy attributed to these groups. Protest groups may be indeed distinguished in relation to the social change they seek and the psychological dynamics they trigger (Kelman & Hamilton, 1989; Passini & Morselli, 2013). In this sense, it may be pertinent to use the distinction between pro-social and anti-social disobedience (Passini & Morselli, 2009). Disobedience is pro-social when it is enacted for the sake of the whole society, including all of its different levels and groups. Instead, it may defined as anti-social when it is enacted in favour of one's own group in order to obtain specific rights. Thus, although both forms of disobedience promote a certain social change, pro-social disobedience promotes a social change addressed to everyone, while anti-social disobedience is not directed to society at large and it preserves or reproduces social inequality (Merton, 1968). As the authority's demands may be legitimate and illegitimate in relation to the democratic principles they back, this classification may be used to consider the legitimacy or illegitimacy of protest groups' claims. In this sense, the claims of a protest can be perceived as morally legitimate - i.e. supporting a social change enacted for the sake of every social group and/or a change benefiting some specific groups that do not clash with any other social groups' rights (unbound) - or illegitimate - i.e. achieving specific and restricted rights for their own group denying the rights of the others (restricted).

What are the consequences of attributing legitimacy to protesters (the claimant) rather than their request (the claim)? On the one side, we may suppose that individuals are more inclined to perceive threatening groups as not legitimate and thus more likely to oppose their protest independently from their claims. On the other side, some individuals may focus mainly on the legitimacy of claims per se, independently from who advanced them. These people would be more likely to support movements whose claims are morally legitimate. In accordance with Kelman and Hamilton's (1989) theory, citizens with a political orientation based on democratic principles and universal values (i.e. value-oriented citizens) should be those who focus on protest groups' claims. These citizens may decide to support protest movements as a function of the social change that they propose. That is, they should evaluate and support just the claims that they perceive as reinforcing basic democratic principles and differentiate them from those that are only aimed at achieving restricted benefits and dominance.

2. HYPOTHESES

The present study examines the effect of the perception of protest groups' legitimacy - in terms of threat - on people's support for their claim. The question is whether supporting or ignoring the protest group's claim depends on the legitimacy of the claim or on the legitimacy attributed to that group. Moreover, the aim is to analyze whether the individual political orientation influences perceptions of legitimacy.

In particular, we hypothesized that (1) in general people tend to consider the legitimacy of the group instead of the legitimacy of the claim to evaluate the protest groups' claim; in this sense, people should give more support to the non-threatening groups than to the threatening groups, irrespective of the legitimacy of their claims. In addition, we expected that (2) value-oriented citizens tend to support only those claims of protest groups that are legitimate - i.e. which support a social change enacted for the sake of every social group - regardless of the legitimacy of the group.

3. METHOD

3.1 Participants

A total of 180 Italian citizens (54.1% men and 45.9 % women) responded by accessing the Website and completing the questionnaire. Participants' ages ranged from 19 to 75 years (M = 41.64, SD = 13.69). Job-wise, 31.6% declared they were clerical workers, 22.5% freelance, 16.5% retired, 2.9% teachers, 2.9% housewives,/househusbands 2.9% unemployed, 2% students and, finally, 18.7% chose "other" or did not answer to the question.

3.2 Procedure

Participants were contacted via the Internet. An online questionnaire was constructed using Limesurvey, a survey-generating tool (http://www.limesurvey.org). A link to the questionnaire was provided to potential participants in an e-mail sent by various methods (e.g. mailing lists, newsgroups). The questionnaire was drafted in Italian. The design included 2×2 conditions: non-threatening vs. threatening type of group and unbound vs. restricted protesters' claim. Participants were assigned to the four web questionnaire conditions using the minute of access to the site - even (Type of Group = Threatening) or odd (Type of Group = Non-Threatening) - and the second of access to the site - even (Protesters' claim = Restricted) or odd (Protesters' claim = Unbound). Using this system, participants were randomly assigned each one to either the non-threatening-unbound (n = 48), the non-threatening-restricted (n = 48), threatening-unbound (n = 43), or threatening-restricted (n = 41) condition. In order to check and prevent a person reentering the survey site, the subject's IP address was monitored.

3.3 Measures

Participants were first asked to read a text in which it was written that in Italy a group of citizens organized a protest movement against the institutions to request free access to dental care that is currently excluded from the national health system and results to be very expensive. They are planning a large protest and a petition to support their cause.

For the participants assigned to the non-threatening condition, the group consisted of homeless people, while for those participants assigned to the threatening condition the group was made up of Romanian immigrants. As in this study we were interested in the evaluation of protest legitimacy and support vis-à-vis a minority group's claim, ingroup-outgroup effects were controlled for by asking people to evaluate the claims of a protester group representing both an outgroup and a minority in all the conditions. Romanians were chosen because they are usually portrayed in the Italian media as a socially distant and threatening minority (see Solimene, 2011). As concerns homeless people, some studies have pointed out that they represent an outgroup, although they should be perceived as Italians (see Harris & Fiske, 2006; Van Zomeren, Fischer & Spears, 2007). These studies asserted that ingroup-outgroup attribution depends from the salience of group membership in a given situation. In the text used, the common nationality fades into the background since it was not evoked.

Concerning unbound vs. restricted claim manipulation, in the unbound condition the claim of the group was generally referred to residents in Italy, while in the restricted condition the claim was referred only to the protest group. Texts were accompanied by a photo of the protest group: i.e. two photos taken from internet depicting one a group of protesting homeless people and one a group of protesting Romanians.

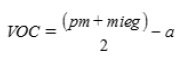

Participants were asked to indicate their perception of the group as a threat ("To what extent should the members of the Romanian [homeless] community be considered threats to society?," from 1 = not at all to 7 = very much) and whether they were willing to support the group's protest ("How much support would you lend to their protest?," acceptance) on a 7-point scale (from 1 = not at all to 7 = very much). They were also asked to indicate if they were willing to join some form of political action such as (1) sign a petition and (2) attend a demonstration against the Government's decision not to support them. Protest willingness was computed as the mean of the two actions (α = .78) on a 7-point scale (from 1 = not at all to 7 = very much). However, willingness to support may not be necessarily followed by a congruent behavior (Klandermans & Oegema, 1987). Willingness to support is a necessary but insufficient factor to predict protest participation. For this reason, in addition to measuring support and willingness, at the end of the questionnaire participants were asked to actually sign or to decline a petition of support for the protest described in the scenario (protest behavior). To test Hypothesis 2 and on the basis of Kelman and Hamilton's theory, a Value-Oriented Citizenship (VOC) index which identified attitudes that reveal a political activism joined with a critical thinking towards authority's governance and an inclusive attitude towards outgroups was computed. The VOC index follows the formula:

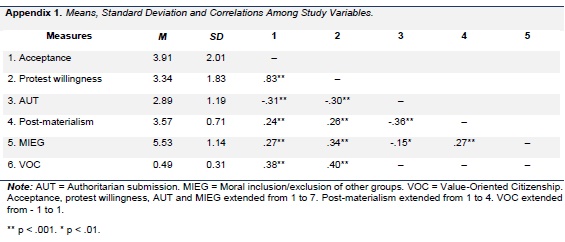

where pm represents the individual score of postmaterialism, a the individual score for authoritarian submission and mieg is the inclusion/exclusion of other group score . Participants to all conditions were therefore asked to answer to these following three measures.

3.3.1 Authoritarian submission

This construct was measured by a 4-item scale based on Right-Wing Authoritarianism (RWA) (Altemeyer, 1996). The questionnaire was constructed and validated by Passini (2008). In particular, the RWA items were split up into items that are pure with respect to the underlying theoretical dimension (authoritarian submission), grammatically simplified and occasionally rephrased. People responded to each item on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). An example of item is "Our country will be great if we do what the authorities tell us to do." Cronbach's1 was .69 and did not increase with the elimination of any item.

3.3.2 Post-materialism

The 4-item post-materialism scale by Inglehart and Abramson (1999) has been used for measuring post-materialist values. The respondents were asked two rank-type questions to choose the highest and next-to-the-highest priority indicator out of a choice from among four values (two materialist and two post-materialist). The materialist values are: (1) keeping order in the nation; (2) fighting rising prices. The post-materialist values are: (3) giving people a greater say in government decisions; (4) protecting freedom of speech. A post-materialism index was constructed scoring 1 = two materialist answers, 2 = materialist (rank 1) and post-materialist (rank 2) answer, 3 = post-materialist (rank 1) and materialist (rank 2) answer, and 4 = two post-materialist answers.

3.3.3 Moral Inclusion/Exclusion of other Groups (MIEG). The moral inclusion/exclusion scale constructed by Morselli and Passini (2012) was used. In particular, each time for three groups - specifically, French, German, and Iranians - the respondents were asked to choose where his or her position lies, on a scale between two statements (one identifying moral exclusion of the group, one moral inclusion of the group). An example of opposition is "It is necessary to avoid any kind of contact with members of this group" versus "It is necessary for all of us to engage in establishing constructive contacts with this group's members." As in the original studies, a one factor solution was considered (α = .88). The higher is the MIEG score, the more inclusive are the attitudes towards the groups considered.

4. RESULTS

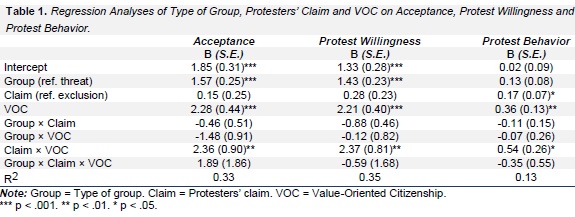

Concerning the type of group condition, participants considered the homeless as a less threatening group (M = 2.51, SD = 1.41) and the Romanians as a more threatening group (M = 3.90, SD = 1.46), F (7, 172) = 42.45, p < .0001, η2 = .17. In order to test the hypotheses a regression analysis was conducted, in which type of group (categorical variable), protesters' claim (categorical variable), VOC (continuous variable) and their interaction were regressed on acceptance, protest willingness and protest behavior (see Table 1). The model were estimated using residuals centering as implemented in the R package pequod (Mirisola & Seta, 2013). The results indicate that all the three models were significant and accounted for 33 % (acceptance), 35 % (protest willingness), and 13% (protest behavior) of the variance. According to Hypothesis 1, type of group was a significant positive predictor (reference: Threat) of all the dependent variables a part protest behavior which was almost significative: B = 1.57, β = .39, t(172) = 6.20, p < .001 (acceptance); B = 1.43, β = .39, t(172) = 6.24, p < .001 (protest willingness); B = 0.13, β = .14, t(147) = 1.80, p = .07 (protest behavior). Protesters' claim was not a significant predictor on all the dependent variables a part protest behavior: B = 0.15, β = .04, t(172) = 0.58, p = .56 (acceptance); B = 0.28, β = .08, t(172) = 1.22, p = .23 (protest willingness); B = 0.17, β = .18, t(147) = 2.29, p < .05 (protest behavior). Thus, in general participants supported the protest of the non-threatening than the threatening group more, while no difference emerged concerning the claim's legitimacy.

In agreement with Hypothesis 2, Claim×VOC was a significant positive predictor of all the three dependent variables: B = 2.36, β = .17, t(172) = 2.61, p < .01 (acceptance); B = 2.37, β = .18, t(172) = 2.91, p < .01 (protest willingness); B = 0.54, β = .17, t(147) = 2.10, p < .05 (protest behavior). Instead, Group×VOC was not a significant predictor on all the dependent variables: B = -1.48, β = -.10, t(172) = -1.63, p = .11 (acceptance); B = -0.12, β = -.01, t(172) = -0.14, p = .89 (protest willingness); B = -0.08, β = -.02, t(147) = -0.27, p < .79 (protest behavior).

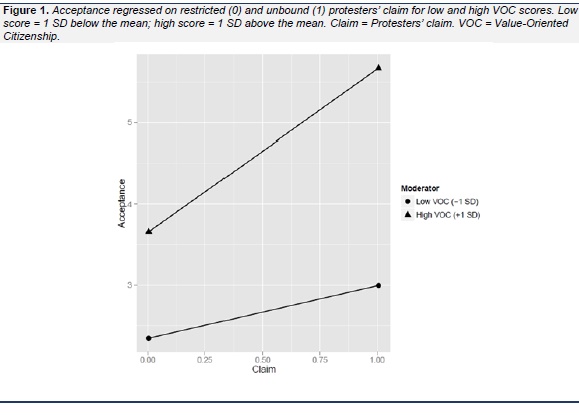

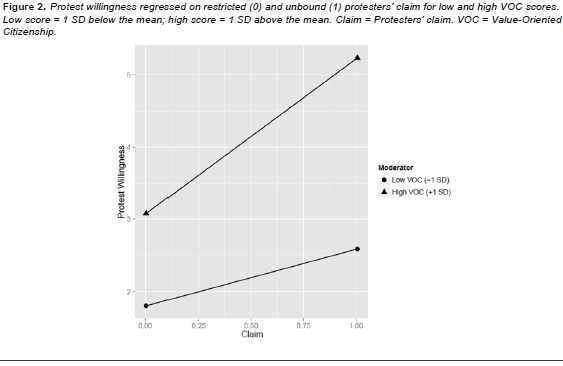

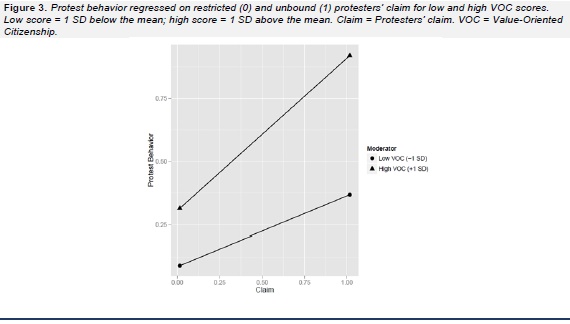

Simple slope analyses were conducted to illustrate the nature of the interactions reported in Table 1 (see Aiken & West, 1991). Simple slopes were estimated with the R package pequod (Mirisola & Seta, 2013), the models controlled for the type of group, the protesters' claim and VOC simultaneously. Figure 1, 2 and 3 provide simple regression lines of acceptance, protest willingness, and protest behaviour as a function of protesters' claim condition at high and low ends (±1 SD) of VOC. Tests of simple slopes revealed that the association between protesters' claim condition and dependent variables were elevated when VOC was high: B = 2.01, t(172) = 2.66, p < .001 (acceptance); B = 2.15, t(172) = 3.15, p < .001 (protest willingness); B = 0.60, t(147) = 2.77, p < .01 (protest behavior). Instead, the association between the type of claim and the dependent variable was weaker when VOC was low: B = 0.65, t(172) = 2.06, p < .05 (acceptance); B = 0.78, t(172) = 2.74, p < .01 (protest willingness); B = 0.28, t(147) = 3.09, p < .01 (protest behavior). Thus, in line with Hypothesis 2, the more participants had high values on VOC the more they tended to accept and to be ready to protest more when the claim was unbound regardless of the type of group who protests (and thus considering only the legitimacy of protest group's claims). Moreover, the more participants had high values on VOC, the more they signed the petition for the protest group's claim when the claim was unbound, while they did not sign it when the claim was restrictive, irrespective of protesters' group membership.

5. DISCUSSION

The issue of the motivations behind the decision as to whether or not to join protest actions is a central topic in social and political psychology. In particular, recent research has underlined the relevance of the identification with social movement organizations as a strong predictor of their support (see van Zomeren et al., 2012). These studies have indeed mainly focused on how the perception of social groups influences the support given to their protest action. The aim of the present research is to consider another variable: i.e., considering not only who the protest groups are (the claimant), but what they are asking for (the claim). That is, adapting the model advanced by Kelman and Hamilton on individual-authority relationship, we analysed whether supporting a protest depends on the legitimacy of the claim advanced or on the legitimacy attributed to that group.

First, results confirm the literature by showing that when people have to choose whether to support a cause or not, the reputation and the common opinion about the group asking for support are relevant elements. Group membership is indeed a core aspect of judgment and determines the ensuing decisions on supporting protest movements. As a matter of fact, people more frequently support those groups that are perceived as not in competition with the ingroup or as deserving their aid, sometimes even regardless of the content of their claims. In line with the approach of social identity theory, vis-à-vis an outgroup protest the support to the protest is neglected when the group is perceived as more threatening. In addition and in line with Moscovici and Pérez's (2007) study on Gypsies, participants declared to be most willing to support the protest when protesters are instead perceived as less threatening. Thus, the common representation of some social groups as threatening or as in opposition to in group's values and culture generally has a great influence on their eventual support.

Second, our results show that the content of the protesters' claim plays no consistent role when people are asked to evaluate the legitimacy of a protest. As we tend to focus on the source and not on the content of information (Pornpitakpan, 2004), we therefore also tend to focus our attention on the person or the group that protests and not on the content of the protest. This is in line with Kelman and Hamilton's (1989) theory on legitimacy by which in the individual-authority relationship the majority tend to focus on the legitimacy of the authority itself and not of the claim issued. The same process was therefore found on the evaluation of protest movements. This issue may constitute an obstacle to the development of a democratic and equal political system: focusing just on the claimant rather than the claim may bring to give support to those groups that show themselves as democratic but who pursue authoritarian policies or to refuse to give support to perceived threatening groups that instead promote a development of democratic values.

Third, our results confirm Kelman and Hamilton's hypothesis that legitimacy is not elaborated in the same way by all the people. In particular, results showed that so-called value-oriented citizens actively formulate, evaluate and question policies more than other people on the basis of the content of the claim. Value-oriented citizens focus more on the claims advanced by the group rather than the source of the claim: when the claim dovetail with their values (i.e. democratic and inclusive values, see Passini & Morselli, 2011) then the eventual perception of group's threat is bypassed. In line with previous results (Kelman & Hamilton, 1989; Passini & Morselli, 2010), value-oriented respondents are the most likely to support protest and to take action when democratic values are at stake. In addition, they also oppose - or at least do not support - conditions which might threaten democracy (i.e. those claims that run counter to the principle of equality) regardless of the democratic appearance of the claimant. This result is particularly noteworthy because it extends the political orientation theories mainly focused on the individual-authority relationship.

Finally, similar results concerning protest intentions were found in respect to the actual respondents' behaviors (i.e. signing the online petition). It should be noted that the statistical significance of the results on protest behavior was lower and that the independent variables explained a less portion of variance. Moreover, in the case of protest behavior, a direct effect of claim was found, by which people sign the petition more for inclusive than exclusive aims while no significant direct effect of the type of group was found. Thus, it seems that when people actually engage in a protest, they take more attention to the content of claims rather than their source. In deciding to give real support to a petition, people perhaps pay more attention to the content of the demand. Finally, the same interaction between VOC and claim concerning intentions of supporting a protest is found on respondents' behavior. This result suggests that the attention to the claim of protest groups follows a value-based orientation to the political system.

The findings of the present study have theoretical as well as practical implications. In addition to the literature investigating protest support, we think that our research adds to these studies a focus on the content of such protests. Indeed, as history teaches us, not all the protests have the same intentions and purposes and not all sustain the enlargement and the development of democratic principles. Thus, in evaluating motivations behind protest support, it is relevant to focus on the claim advanced by protest groups apart from other aspects, such as system justification and social identification with the protest groups. We think that considering the content of the claim adds some understanding of the dynamic between social stability and social change. Indeed, a theory conceiving the distinct effects of considering the legitimacy of the claimant vs. the claim, adds insight to the mechanism that lead to the success or failure of protests and minorities' demands.

The results of this study also suggest that people with a political orientation to values - i.e. value-oriented citizens - are more likely to be evaluative to both authority and the protest group's claims, and to engage in action. Thus, our data recommend a theoretical advancement in Kelman and Hamilton's (1989) model of political orientation that considers that political orientation has an influence not only upon the expectations of the authority and the evaluation of top-down policies, but also in the assessment of bottom-up proposals (see Passini & Morselli, 2013). In addition, our findings confirm and develop previous studies focused on the importance of the general population - the so-called silent or powerless majority (Chryssochoou & Volpato, 2004) - in fostering social changes. The "silent majority" may be considered as a passive advocate of social change - "torn between the influence of the majority/power that aims to reproduce its dominance (system-justification) and the minority that aims to influence them toward change" (Chryssochoou & Volpato, 2004, p. 360) - if and only if it is not aware of what change it is actually supporting. Instead, the silent majority becomes a "participative majority" if it is able to recognize those causes that promote the enhancing of democracy and universal ideals instead of reducing them. In this sense, people high on VOC tend to actively evaluate and question policies; in other words, those citizens conceive their citizenship as requiring active participation (Kelman & Hamilton, 1989). Thus, the study of this type of citizens can bring new insight on the bottom-up processes of social change, that is on the dynamic by means of which a certain type of relationship between some individuals or groups and the authority can lead to an extended change in the whole of society.

These issues have clear applicative implications to enhance citizens' active participation. Indeed, participation can be enhanced by promoting at the same time the active evaluation of authority's legitimacy but also the active evaluation of protesters' claims. Once they have gained people's support, social protest movements might degenerate into authoritarian and exclusive decision-making system. Thus, in order to protect society and democracy a correct evaluation of protesters' claims is essential to protect from anti-democratic forces. A key recommendation for practitioners may be to promote educational programs and projects designed to develop a more mature relationship with the political system based on an active evaluation and assessment of the policies and ideologies of both authorities and protest movements.

This research has some limitations which should be borne in mind for future research. The first concerns the types of groups chosen for the research which participants had to lend their support to, i.e. Romanians and homeless people. In the future, the analysis of the claimant's legitimacy should consider other groups. For instance, groups perceived more "threatening" - e.g. radical extremists - should be considered. A second limitation regards the unbound-restricted condition. Indeed, no control on the efficacy of this condition was made. That is, checking whether participants effectively perceived one condition as being more restrictive than the other. Then, in future studies other claims should be analyzed. Finally, future studies may analyze the joint effects of social identification with a particular group and three orientations identified by Kelman and Hamilton (1989). Indeed, social identification is a predictor of collective action that again seems to be focused on the claimant and not on the claim of the protest (see van Zomeren, Postmes, Spears, 2008). For better comprehend support to protest, it may be relevant to join prediction by both social identity theory and political orientation theory.

In conclusion, the results presented in this article confirm the relevance of an approach to the study of protest movements which consider the content of such protests and do not just focus on the protesters. This is considered relevant in a period in which media, politicians and the population in general more frequently discuss about the way protest movements exhibit themselves rather than what they are asking for. Analyzing the content of protests and its effects on protest support may be relevant for social scientists to advance their research into the understanding of the development of democratic vs. authoritarian values.

Notas

1 In order to compute VOC index, variables were re-scaled to range from 0 to 1. Thus the VOC index ranged from -1 (high authoritarian attitudes and low on democratic values and inclusion) to 1 (high on democratic values and inclusion and low on authoritarian attitudes). In Appendix, means, standard deviations and correlations of all the variables of the research are presented.

6. REFERENCES

Aiken, L. S. & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Altemeyer, B. (1996). The authoritarian specter. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Bruce St John, R. (2008). Redefining the Libyan revolution: the changing ideology of Muammar al-Qaddafi. The Journal of North African Studies, 13(1), 91-106. [ Links ]

Chryssochoou, X. & Volpato, C. (2004). Social influence and the power of minorities: An analysis of the communist manifesto. Social Justice Research, 17, 357-388. [ Links ]

Giugni, M. (1999). How social movements matter: Past research, present problems, future development. In M. Giugni, D. McAdams & C. Tilly (Eds.), How social movements matter (pp. 13-32). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [ Links ]

Harris, L. T. & Fiske, S. T. (2006). Dehumanizing the lowest of the low: Neuroimaging responses to extreme out-groups. Psychological Science, 17, 847-853. [ Links ]

Inglehart, R. & Abramson, P. R. (1999). Measuring postmaterialism. American Political Science Review, 93(3), 665-677. [ Links ]

Kelly, C. & Breinlinger, S. (1996). The social psychology of collective action. Basingstoke, UK: Taylor & Francis. [ Links ]

Kelman, H. C. (2001). Reflections on social and psychological processes of legitimization and delegitimization. In J. T. Jost & B. Major (Eds.), The psychology of legitimacy: Emerging perspectives on ideology, justice, and intergroup relations (pp. 54-73). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Kelman, H. C. & Hamilton, V. L. (1989). Crimes of obedience. Toward a social psychology of authority and responsibility. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Klandermans, B. & Oegema, D. (1987). Potentials, networks, motivations, and barriers: Steps towards participation in social movements. American Sociological Review, 52, 519-531. [ Links ]

Klandermans, B. (2002). How group identification helps to overcome the dilemma of collective action. American Behavioral Scientist, 45, 887-900. [ Links ]

Klein, O., Spears, R. & Reicher, S. (2007). Social identity performance: Extending the strategic side of SIDE. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 11, 28-45. [ Links ]

Jost, J. T., Chaikalis-Petritsis, V., Abrams, D., Sidanius, J., Van Der Toorn, J. & Bratt, C. (2012). Why men (and women) do and don't rebel effects of system justification on willingness to protest. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 38(2), 197-208. [ Links ]

Meeus, J., Duriez, B., Vanbeselaere, N., Phalet, K. & Kuppens, P. (2009). Examining dispositional and situational effects on outgroup attitudes. European Journal of Personality, 23, 307-328. [ Links ]

Merton, R. K. (1968). Social theory and social structure. New York: The Free Press. [ Links ]

Mirisola, A. & Seta, L. (2013). Pequod: Moderated regression package. R package version 0.0-3. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=pequod. [ Links ]

Morselli, D. & Passini, S. (2012). Measuring moral inclusion: A validation of the inclusion/exclusion of other groups scale. LIVES Working Papers, 14, 1-18. [ Links ]

Moscovici, S. & Pérez, J. A. (2007). A study of minorities as victims. European Journal of Social Psychology, 37, 725-746. [ Links ]

Mugny, G. (1982). The power of minorities. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Mugny, G. & Pérez, J. A. (1991). The social psychology of minority influence. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Norris, P. (2002). Democratic phoenix: reinventing why political activism. New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Passini, S. (2008). Exploring the multidimensional facets of authoritarianism: Authoritarian aggression and social dominance orientation. Swiss Journal of Psychology, 67(1), 51-60. [ Links ]

Passini, S. & Morselli, D. (2009). Authority relationships between obedience and disobedience. New Ideas in Psychology, 27, 96-106. [ Links ]

Passini, S., & Morselli, D. (2010). Disobeying an illegitimate request in a democratic or authoritarian system. Political Psychology, 31, 341-356. [ Links ]

Passini, S. & Morselli, D. (2011). In the name of democracy: Disobedience and value-oriented citizenship. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 21, 255-267. [ Links ]

Passini, S. & Morselli, D. (2013). The triadic legitimacy model: Understanding support to disobedient groups. New Ideas in Psychology, 31, 98-107. [ Links ]

Pornpitakpan, C. (2004). The persuasiveness of source credibility: A critical review of five decades' evidence. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 34, 243-281. [ Links ]

Rucht, D. (2004). Movement allies, adversaries, and third parties. In D. A. Snow, S. A. Soule & H. Kriesi (Eds.), The Blackwell companion to social movements (pp. 197-216). Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub. [ Links ]

Simon, B. & Klandermans, B. (2001). Politicized collective identity: A social psychological analysis. American Psychologist, 56, 319-331. [ Links ]

Simon, B., Loewy, M., Stürmer, S.,Weber, U., Kampmeier, C., Freytag, P., Habig, C. & Spahlinger, P. (1998). Collective identity and social movement participation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 646-658. [ Links ]

Smith, H. J., Pettigrew, T. F., Pippin, G. M. & Bialosiewicz, S. (2012). Relative deprivation a theoretical and meta-analytic review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 16(3), 203-232. [ Links ]

Solimene, M. (2011). `These Romanians have ruined Italy'. Xoraxane Roma, Romanian Roma and Rome. Journal of Modern Italian Studies, 16, 637-651. [ Links ]

Stewart, A. L., Pratto, F., Zeineddine, F. B., Sweetman, J., Eicher, V., Licata, L. van Stekelenburg, J. (2015). International support for the Arab Uprisings: Understanding sympathetic collective action using theories of social identity and social dominance. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, in press. [ Links ]

Tajfel, H. & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of social conflict. In W. G. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33-47). Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole. [ Links ]

Thomas, E. F. & Louis, W. R. (2014). When will collective action be effective? Violent and non-violent protests differentially influence perceptions of legitimacy and efficacy among sympathizers. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 40(2), 263-76. doi:10.1177/0146167213510525. [ Links ]

van Zomeren, M., Fischer, A. & Spears, R. (2007). Testing the limits of tolerance: How intergroup anxiety amplifies negative and offensive responses to out-group-initiated contact. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33, 1686-1699. [ Links ]

van Zomeren, M., Postmes, T. & Spears, R. (2008). Toward an integrative Social Identity model of Collective Action: A quantitative research synthesis of three socio-psychological perspectives. Psychological Bulletin, 134, 504-535. [ Links ]

van Zomeren, M., Postmes, T. & Spears, R. (2012). On conviction's collective consequences: Integrating moral conviction with the social identity model of collective action. British Journal of Social Psychology, 51, 52-71. [ Links ]

7. APPENDIX