Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

International Journal of Psychological Research

Print version ISSN 2011-2084

int.j.psychol.res. vol.10 no.1 Medellín Jan./June 2017

https://doi.org/10.21500/20112084.2338

DOI: https://10.21500/20112084.2338.

Subtle Prejudice and Conformism: The Intergroup Indifference

El prejuicio y el conformismo sutiles: la indiferencia del intergrupo

Stefano Passini1*

1 Department of the Education Sciences, University of Bologna, Italy.

Corresponding author: s.passini@unibo.it.

Manuscript received 05-06-2016; revised 16-09-2016; accepted 30-10-2016.

ABSTRACT

In understanding the dynamics that lead to the restriction of human rights, social psychology research has mainly focused on the concept of the banality of evil and of obedience to destructive and immoral orders. However, some authors have also underlined the relevant role of by standing and, in general, of indifference in supporting authoritarian policies on a par with the obedience to authority. The aim of this research was to study the notion of intergroup indifference, defined as being uninterested in problems affecting other social groups. The hypothesis was that indifferent people should be characterized by subtle modalities of obedience to authority and prejudicial attitudes, by exclusive attitudes and by conformist and traditional positions. Results showed that participants who respond with an indifferent stance to some parliamentary bills related to arbitrary policies towards minorities appear to be characterized by similar scores on subtle prejudice, submission to authority, conventionalism, willingness to protest, conservative values and moral exclusion attitudes to those people who openly support such policies. Instead, these two groups differ as concerns more overt hostile attitudes. These data suggest that indifferent people have a role in supporting arbitrary policies. As a theoretical implication, future research should consider that intergroup dynamics do not involve just people who obey or disobey authority. People who apparently do not take up any stance before an authority's policies should be considered as well.

Keywords: Intergroup indifference; authoritarianism; obedience; prejudice; values.

RESUMEN

En la comprensión de la dinamica que conduce a la restricción de los derechos humanos, la investigación de la psicología social se ha centrado principalmente en el concepto de la banalidad del mal y de la obediencia a órdenes destructivas e inmorales. Sin embargo, algunos autores también han subrayado el papel relevante de la posición y en general de la indiferencia en el apoyo a las políticas autoritarias, a la par con la obediencia a la autoridad. El objetivo de esta investigación fue estudiar la noción de indiferencia intergrupal, definida esta como el desinterés de los problemas que afectan a otros grupos sociales. La hipótesis era que las personas indiferentes debían caracterizarse por sutiles modalidades de obediencia a la autoridad y actitudes prejuiciadas por actitudes exclusivas, por posiciones conformistas y tradicionales. Los resultados mostraron que los participantes que responden con una postura indiferente a algunos proyectos de ley parlamentarios relacionados con políticas arbitrarias hacia las minorías, parecen caracterizarse por puntuaciones similares en prejuicios sutiles, sumisión a la autoridad, convencionalismo, voluntad de protesta, valores conservadores y actitudes de exclusión moral hacia esas personas que apoyan abiertamente esas políticas. En cambio, estos dos grupos difieren en cuanto a las actitudes manifiestas más hostiles. Estos datos sugieren que las personas indiferentes tienen un rol en apoyar políticas arbitrarias. Como implicacion teórica, la investigación futura debe considerar que la dinámica intergrupal no involucra sólo a las personas que obedecen o desobedecen a la autoridad, las personas que aparentemente no toman ninguna posición antes de las políticas de una autoridad deben ser consideradas también.

Palabras Clave: Indiferencia entre grupos; autoritarismo; obediencia; prejuicio; valores.

1. INTRODUCTION

Towards the end of 2013, Italian public opinion was shocked by a video broadcast by the state TV channel. Shot in an immigrant detention center on the island of Lampedusa, the video shows migrants in a line, some of them naked in the cold weather, ready to be "cleansed" by an aid worker with a pump which sprayed them with a substance supposed to protect from scabies1. This video conjured up memories of severe abuse images from the past (e.g. Jews victimized by Nazis) and led the European Union to investigate the treatment of immigrants and to threaten penalties for Italy. However, despite the outrage that emerged among both political institutions and the general population, a few weeks later the immigrant detention centers once again became forgotten places, invisible to most people. Likewise, the almost daily infringement of human rights that affects some minorities in Italy also vanishes from the public debate. In 2011, in one of the main Italian daily newspapers, Corriere delia Sera, the journalist Claudio Ma-gris discussed the issue that migrant tragedies had disappeared from the front pages of newspapers and that this was a sign of an increasing indifference of media and Italian people towards immigrants themselves2. All these episodes bring to light one of the most relevant problems in a time of multicultural-ism: the issue of the invisibility of some minorities and the indifference of the majority towards them.

In understanding the dynamics that led to some severe human rights abuses occurring in the past and the active and passive acceptance of such policies by the population, since Arendt (1963) analysis and Milgram (1974) famous experiment, social psychology research has mainly focused on the concept of the banality of evil. This notion refers to evil deeds perpetrated thoughtlessly and driven by blind or more engaged obedience to authority's demands (Arendt, 1963; Mil-gram, 1974). However, this notion does not embrace all the psychosocial dynamics behind these events. Bauman (1989) underlined that the indifference and the silence of the population, and not just their obedient attitudes towards authority's demands, were relevant factors that contributed to perpetrating severe abuses as well. Along the same lines, Allport (1954) has already considered that positivity toward ingroups does not necessarily imply direct hostility toward outgroups, as a range of other attitudes may be directed toward them, going from disdain and hatred, to unconcern and indifference (Brewer, 1999). In the present article, the notion of intergroup indifference will be studied with the aim of understanding how being uncaring to policies and human rights abuses is linked to subtle modalities of obedience to authority and prejudicial attitudes, as well as to conformist positions. In the next paragraph, the notion and the characteristics of intergroup indifference will be outlined. After that, the other variables used in the research will be briefly presented.

1.1 The Notion of Intergroup Indifference

As Bauman asserted in 1989, rather than by the uproar of emotions, arbitrary and undemocratic policies risk being supported by "the dead silence of unconcern" (p. 75). By studying the origins of genocides and mass violence in general, some studies (e.g. Monroe, 2008; Staub, 2014) have indeed observed the relevant role of passive bystanders in non-obstructing or even fostering perpetrators (by making their actions acceptable and even justified). As Monroe (2008) pointed out, when most people ignore other people's suffering, they provide "indirect or tacit support for the conditions that engendered such misfortune" (p. 732). In this sense, Staub (2014) suggested that inaction of bystanders is not to be considered just as passive but gets nearer to a sort of complicity. Bystanders are indeed not "doing nothing," as their apparent indifference is an act that gives perpetrators consent for what would otherwise be regarded at least as morally controversial (Johnston, 2013). In this sense, indifference towards the other may be considered as a powerful tool for supporting authoritarian policies on a par with the obedience to authority identified by the socalled banality of evil.

This complicit role of bystanders and indifferent people in supporting restrictions of human rights also occurs in more contemporary societies that are affected by a gradual and progressive invisibility of immigrants and minorities (Pratto, Henkel, & Lee, 2013). These people are either hidden or omnipresent but in both cases the categories used to indicate them in some way lose their function of specifying a distinct social figure (Stichweh, 1997) and provide support to create a distance (a wall) of indifference and unconcern. Bar-On (2001) suggests that contemporary individualistic cultures in many ways push people to behave as bystanders and to mind one's own business (Johnston, 2013). In this sense, Stichweh (1997) pointed out that the notion of indifference goes beyond the friend vs. enemy dichotomy by creating a third (non-) status of being neither kin nor stranger, but invisible and in some way a non-person.

As indifference is a term that may have different meanings depending on its context of use, in this manuscript it is discussed referring to a definition focusing on an intergroup dimension. That is, more than to a personal feeling of apathy towards one's own life or an indifference as an abstraction from others finalized to the perpetration of violence against them (see Zamperini, 2013), it is defined as being referred to a condition of being uncaring to problems affecting other social groups (e.g. human rights): an intergroup indifference which is based on an ingroup-outgroup dynamics characterized by the "us vs. them" dimension. Intergroup indifference may in this sense takes the form of a total unconcern and uninterest in others' needs or may be exemplified by a priority given to ingroup needs over those of other social groups to the point that the latter are simply not considered.

1.2 The Psychology of the Indifferent

What characterizes a person who is indifferent towards other groups as concerns social psychological variables? What is the difference between the indifferent person and a person who chooses to agree or disagree with some arbitrary policies? A first variable to be considered, as suggested by some of the previously mentioned literature (see Bauman, 1989; Brewer, 1999) is prejudice, both in its classical usage as in its more modern form. Indeed, we can reasonably suppose that if more classical (or as it is defined "blatant", see Pettigrew & Meertens, 1995) prejudice should clearly distinguish people who assent or oppose discriminatory policies, subtle forms of prejudice should be used by the indifferent person as well. As some authors (e.g. Dovidio & Gaertner, 2004; Ellemers & Barreto, 2009) have pointed out, since "old-fashioned" prejudice has become more socially unacceptable, discriminatory attitudes and behaviors have changed face, i.e. from overt and blatant expressions to more subtle forms. These modern expressions of bias express the same discriminatory beliefs but more indirectly (Ellemers & Barreto, 2009). The idea behind this research is that indifference towards other social groups may conceal a subtle expression of prejudice towards them. That is, the indifferent person may not blatantly discriminate the other social groups, but may do so by using more subtle ways so as not to consider their problems. For instance, Costello and Hodson (2011) have pointed out that host societies often consider outgroups themselves responsible for not solving their problems (e.g. through hard work or adapting to the dominant culture) and this shift of responsibility upon them (i.e. a subtle form of prejudice, see Dovidio & Gaertner, 2004) is connected to attitudes and behaviors of indifference towards helping immigrants. As Brewer (1999) has pointed out, many studies have shown that the essence of "subtle racism" is not the presence of strong negative attitudes toward the outgroups but the absence of positive sentiments toward those groups.

Other variables that help to distinguish indifferent people should be authoritarianism and social dominance orientation. As seen previously, indifference may be indeed considered as another way to adapt to authority's demands (see Bauman, 1989). As concerns authoritarianism, the most used conceptualization of the past few decades is Right-wing authoritarianism (RWA, Altemeyer, 1996). RWA is defined and measured by the covariation of three attitudinal clusters: submissiveness to established authorities (authoritarian submission), strict adherence to conventional norms and values (conventionalism), and attitudes fostering harsh and coercive social control towards who are perceived as targets according to established authorities (authoritarian aggression). Given that authoritarian aggression is a more overt and tougher stance, it is reasonable to expect that indifferent people should be less characterized by these more aggressive and exposed attitudes of derogation. Instead, they should attach a certain importance to submission and conformism to authority, as expressed by the other two clusters. Moreover, since authoritarianism describes attitudes of not questioning authority's demands (Altemeyer, 1996; Passini & Morselli, 2009, 2015), indifferent people should be also less willing to protest against institutions and authorities.

As concerns social dominance orientation (SDO), this construct identifies an individual's preference for hierarchical (versus egalitarian) intergroup relations within a society (Pratto, Sidanius, Stallworth, & Malle, 1994). That is, such an orientation sustains the superiority of one's ingroup over out-groups and legitimizes overt discrimination and domination over these outgroups. As for authoritarian aggression, given that SDO supports overt and exposed attitudes of prejudice towards outgroups (e.g. Kteily, Sidanius, & Levin, 2011; Passini & Morselli, 2016a), it is reasonable to expect that indifferent people should be less characterized by attitudes of dominance than people who blatantly follow authority's requests.

Furthermore, another interesting variable to be analysed when distinguishing indifferent people's psychology should be values. Indeed, values are considered as a mirror of the way people perceive and interpret the society all around as well as of the attitudes and actions they perform in the everyday life (Knafo, Sagiv, & Roccas, 2011). Values are defined as trans-situational goals that serve as a guiding principle in one's own life (Schwartz, 1992). Schwartz (1992) developed a structural model of values that distinguishes between ten content types representing the basic motivations characterizing people in any given society. These ten value types are universalism (protection for the welfare of all people); benevolence (preservation of the welfare of people with whom one is in frequent personal contact); conformity (restraint of actions that violate social expectations); tradition (respect of the traditional customs); security (safety and stability of society); power (social status and control over people and resources); achievement (personal success); hedonism (pleasure and self-gratification); stimulation (excitement and novelty in life); and self-direction (independent thought and action). In line with the previous variables, indifferent people should be characterized by those conservative values connected with submission to authority and conventionalism (i.e. conformity, tradition and security, see Duriez & Van Hiel, 2002).

Finally, another variable that could be analyzed in relation to indifference are the moral exclusion processes. Bystanders are indeed characterized by a general moral abandonment of victims and a redrawing of moral obligations to exclude them (Verdeja, 2012). As Opotow (1990) has pointed out, some of the processes used to exclude other social groups from the community to whom moral values and rules of justice apply (namely one's own moral community) are based on making them invisible and non-existent (see Passini, 2011). For instance, this may happen through the processes of dehumanization and deindividuation. These processes were largely used by Nazis to pursue the Jews: "The Nazis particularly excelled in a third method. [... ] This was the method of making invisible the very humanity of the victims. [... ] To render the humanity of victims invisible, one needs merely to evict them from the universe of obligation" (Bauman, 1989, p.27). Indeed, minorities' invisibility is a relevant factor in fostering indifferent attitudes towards their problems. Thus, it is reasonable to expect that indifferent people should be also characterized by those processes of moral exclusion of the other social groups from one's own moral community.

1.3 Hypotheses

The aim of the present research was to identify such people who tend to be indifferent and who assume an uninterested stance in the face of social and legal norms that arbitrarily affect minority groups and restrict their rights. The notion was that indifferent people, by not holding any stances, share some socio-psychological characteristics with those who openly approve such rights restrictions. That is, although indifferent people should be less openly aggressive and prejudicial towards minority groups and less dominant than supporters of restrictive parliamentary bills, they should have similar scores on subtle attitudes of prejudice as well as on reactionary values associated with system justification, like values pertaining to traditions, security and conformism, and on attitudes of moral exclusion.

In particular, the hypothesis was that people indifferent to the possible endorsement of parliamentary bills restricting some minority groups' rights should attach similar greater importance to values concerning traditions, conformity, and security than those who openly approve them. Moreover, these two groups should have similar high scores on attitudes of submission and conventionalism to authority, on subtle prejudicial attitudes, as well as lower scores on willingness to protest against the system and on moral exclusion processes than those people who oppose the endorsement of parliamentary bills. Instead, indifferent people should have lower scores than open supporters of bills on those variables that convey open aggression towards minorities, such as blatant prejudice, authoritarian aggression, and social dominance orientation.

Two studies were carried out. In Study 1, indifference was analyzed in relation to authoritarianism, prejudice, values and protest attitudes. In Study 2, modern racism, SDO and moral exclusion attitudes were considered.

2. STUDY 1

2.1 METHODS

2.1.1 Participants

Participants were contacted via the Internet. An online questionnaire was constructed using Limesurvey, a survey - generating tool (http://www.limesurvey.org). The questionnaire was publicly accessible and an invitation with the link to the questionnaire was emailed to the potential participants by various methods (e.g. mailing lists, newsgroups, social networking services). In particular, a university mailing list was used. The questionnaire was written in Italian. In order to check and prevent a person reentering the survey site, the subject's IP address was monitored. Participants were informed that their involvement was voluntary and that their responses would be anonymous and confidential. No compensation was offered. The procedure used satisfied the ethical requirements set by the APA and the participants agreed to informed consent prior to participation.

A total of 190 Italian citizens (70% women) responded by accessing the website and filling out the questionnaire. Participant ages ranged from 16 to 62 years (M = 28.68, SD = 10.30). They were mainly born in the north of Italy (77.2%), while only the 10.6% and the 12.2% came from the centre and the south, respectively. As regards their level of education, 4.3% declared they had finished middle school, 63% declared they had obtained a high school diploma, 29.9% had a university degree and 2.7% a masters of Ph.D. qualification. Job-wise, 57.1% stated they were university students, 17.9% clerical workers, 9.5% self-employed, 5.4% factory workers/craftsmen, 3% teachers, 3% unemployed, and, finally, 4.2% chose "other."

2.1.2 Measures

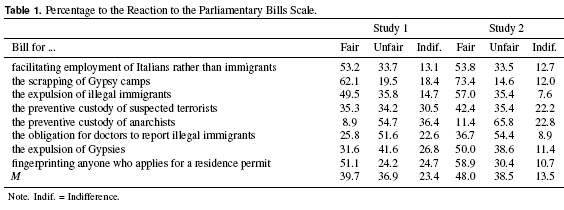

Reaction to the parliamentary bills. Participants were asked to choose their reaction ("I find it fair," "I find it unfair" and "I am indifferent") to eight parliamentary bills related to some social groups (e.g. "bill for the elimination of Gypsy camps," see all items in Table 1). All the bills were introduced to the participants as real bills in discussion in the Italian parliament.

Activism orientation scale. Participants completed the activism orientation scale (AOS, Corning & Myers, 2002), composed by 10 items referred to future behavioral intention to protest. They were asked to rate on a 7-point scale (from 1 = "not at all" to 7 = "very much") the likelihood they will engage in various activist behaviors in the future (e.g. sign a petition for a political cause; send a letter or email about a political issue to a public official). A principal axis factoring of the items was computed. The scree test revealed a clear break between the first and second eigenvalue: 5.10, 1.06, 0.77, 0.70, etc. Hence, only one factor was retained from the analysis and an AOS index was computed as the mean of all the items (Cronbach's a = .89).

Values. Values were measured with the 21-items version of the Portrait Values Questionnaire (PVQ; Schwartz et al., 2001). The PVQ includes 21 short verbal portraits of different people, each implicitly pointing to the importance of a value. For example, "It is important to him to listen to people who are different from him. Even when he disagrees with them, he still wants to understand them" describes a person for whom universalism values are important. Respondents indicate how similar the person is to themselves on a scale ranging from "not like me at all" (1) to "very much like me" (6). The PVQ measures each of the 10 motivationally distinct types of values (benevolence, tradition, conformity, security, power, achievement, hedonism, stimulation, and self-direction, and universalism) with two items (except universalism with three).

Authoritarianism. This construct was measured by a 12-item scale based on Right-Wing Authoritarianism (RWA) (Al-temeyer, 1996). The scale was constructed and validated by Passini (2008). People responded to each item on a 7- point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). As in the original study, three underlying theoretical dimensions were computed: authoritarian submission (4 items, a = .75, e.g. "our country will be great if we do what the authorities tell us to do"), authoritarian aggression (3 items3, a = .70, e.g. "our government has to eliminate any opponents.") and conventionalism (4 items, a = .73, e.g. "our country will be great if we respect our traditions.").

Subtle and blatant prejudice. The subtle-blatant prejudice scale (10 items on a 7-point scale from 1 = "strongly disagree" to 7 = "strongly agree") by Pettigrew and Meertens (1995) was used with specific reference to Romanian immigrants. Romanians were chosen because they are usually portrayed in the Italian media as a socially distant and threatening minority (see Solimene, 2011). Cronbach's alpha was .75 for blatant subscale (5 items) and .76 for subtle subscale (5 items). Some sample items of the scale are: "It is just a matter of some people not trying hard enough. If Romanians would only try harder they could be as well off as Italian people" (subtle), "Romanians have jobs that the Italian should have" (blatant).

Demographics and politics. Participants indicated their age, gender, level of education, job, importance given to politics (from 1 = "not at all" to 7 = "very much") and political affiliation (from 1 = "extreme left" to 10 = "extreme right").

2.2 Results

Percentage means on the reaction to the parliamentary bills (see Table 1) show that 23.4% of participants declared they were indifferent to some of them. Specifically, the parliamentary bill focused on the elimination of Gypsy camps was the most supported ones, while the preventive detention of anarchists was the most opposed (and the one that had the highest number of indifferent responses).

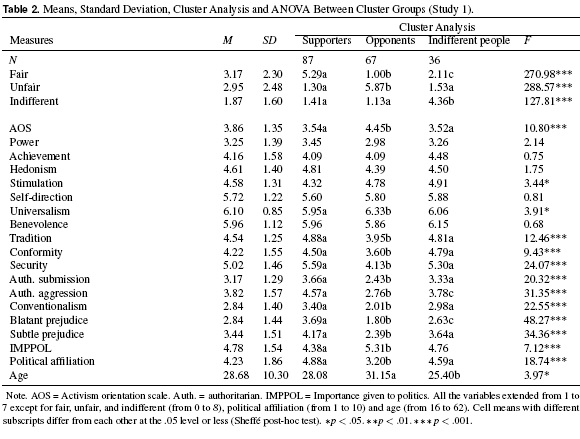

As concerns the means on the other variables (see Table 2 left part), participants had medium scores on AOS, they attach very high importance to universalism, benevolence and self-direction values, high importance to security, hedonism, stimulation and tradition, medium importance to conformity and achievement and low importance to power. They had medium scores on authoritarian aggression and low scores on authoritarian submission and conventionalism, and both dimensions of prejudice. Finally, they attached high importance to politics and they tended to be politically situated in the center-left.

In order to identify groups of participants who reacted differently to the parliamentary bills, a K-Means clustering procedure was performed on the number of times participants declared they perceived the bills as being fair, unfair or else they felt indifferent to them (on a scale from 0 to 8, corresponding to the eight parliamentary bills). Three groups were obtained after 4 iterations (see Table 2 right part). People who mainly considered the parliamentary bills fair made up the first group (called supporters). People who mainly considered the parliamentary bills unfair made up the second group (called opponents). Finally, people who mainly felt indifferent to the parliamentary bills made up the third group (called indifferent people).

An ANOVA between the cluster groups was performed on the other variables. As hypothesized, supporters and indifferent people had similar scores and significantly higher than the opponents on values of tradition, conformity and security, on authoritarian submission and conventionalism and on subtle prejudice. Moreover, supporters and indifferent people had similar scores and were significantly higher than opponents on AOS. As hypothesized, opponents and indifferent people were both significantly lower than supporters on blatant prejudice and authoritarian aggression (even if indifferent people are significantly higher of opponents as well). Lastly, indifferent people also had lower scores on universalism than opponents.

Finally, as concerns age and politics, opponents were the one that attached the most importance to politics and were more politically situated in the Left-wing compared to supporters and indifferent people. As concerns age, indifferent people were the youngest, while opponents the eldest.

3. STUDY 2

3.1 Methods

3.1.1 Participants

Participants were contacted via the Internet using the same procedure of the previous study. The mailing lists used were different from those used in Study 1. A total of 158 Italian citizens (64.6% women) responded by accessing the website and filling out the questionnaire. Participant ages ranged from 19 to 66 years (M = 31.43, SD = 10.60). They were mainly born in the north of Italy (62.7%), while only the 10.9% and the 23.1% came from the centre and the south, respectively, and 2. 6% were born abroad. As regards their level of education, 8.3% declared they had finished middle school, 61.5% declared they had obtained a high school diploma, 27.6% had a university degree and 2.6% a masters of Ph.D. qualification. Job-wise, 32.5% stated they were clerical workers, 30.5% university students, 7.1% respectively factory workers/craftsmen, self-employed, teachers, and unemployed, and, finally, 8.3% chose "other."

3.1.2 Measures

Reaction to the parliamentary bills. Participants responded to the same scale used in Study 1 (see all items in Table 1).

Social dominance orientation. Social dominance orientation was measured with the 4-item version of the SDO scale Pratto et al. (1994). A sample item of the scale is "Some groups of people are simply inferior to other groups." Reliability of the scale was a = .72.

Modern racism. To measure modern racism, five items on a 7-point scale (ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree) from the modern sexism scale (Wohl & Branscombe, 2009). A sample item is "Discrimination against immigrants is no longer a problem in Italy". An overall anti-immigrants racism score was calculated by averaging the five items (a = . 80).

Moral inclusion/exclusion of the other groups (MIEG). The moral inclusion/exclusion scale constructed by Passini and Morselli (2016b) was used. Participants were asked in a first step to list from 2 to 4 ethnic/cultural groups other than their own that lived in their neighborhood. Subsequently, the MIEG items were prompted referring to the listed groups. The most frequent groups nominated were: Romanians ( f= 55), Chinese (f = 50), Moroccans (f = 41), Albanians (f = 23) and Indians (f = 19). Then, each time for each group the respondents were asked to choose where their position lies, on a scale between two statements (one identifying moral exclusion of the group, one moral inclusion of the group). An example of opposition is "It is necessary to avoid any kind of contact with members of this group" versus "It is necessary for all of us to engage in establishing constructive contacts with this group's members." As in the original studies, a one factor solution was considered (a = .95). The higher is the MIEG score, the more inclusive are the attitudes towards the groups considered.

Demographics and politics. Participants indicated their age, gender, level of education, job, importance given to politics (from 1 = "not at all" to 7 = "very much") and political affiliation (from 1 = "extreme left" to 10 = "extreme right").

3.2 Results

Percentage means on the reaction to the parliamentary bills (see Table 1) show that 10.9% of participants declared they were indifferent to some of them.

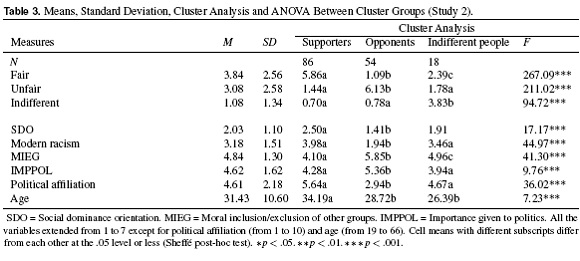

As concerns the means on the other variables (see Table 3 left part), participants had low scores on SDO and modern racism and medium scores on MIEG. Moreover, they attached medium-high importance to politics and they tended to be politically situated in the center.

As in Study 1, a K-Means clustering procedure was performed on the number of times they declared they perceived the bills as being fair, unfair or else they felt indifferent to them. As in Study 1, three groups were obtained after 2 iterations (see Table 3, right part): i.e., supporters, opponents, and indifferent.

An ANOVA between the cluster groups was performed on the other variables. As hypothesized, supporters and indifferent had similar score and significantly higher than the opponents on modern racism. Moreover, they had similar score and significantly lower than the opponents on MIEG. As hypothesized, opponents and the indifferent had similar scores and were significantly lower than supporters on SDO. Finally, as concerns age and politics, the opponent group was the one that attached the most importance to politics and was more politically situated in the Left-wing. As concerns age, indifferent participants were the youngest.

4. DISCUSSION

The aim of the present research was to study the notion of intergroup indifference, in this context defined as not taking an interest in other social groups' rights or difficulties as well as being uninterested with regard to arbitrary policies against them. In particular, this article is focused on the issue that indifferent people should be characterized by subtle methods of obedience to authority and prejudicial attitudes, by the moral exclusion of other groups from one's own moral community, as well as by conformist and traditional stances. The results confirm these hypotheses. Indeed, those participants who mainly respond with an indifferent position with regard to the parliamentary bills used in the research appear to be characterized by similar scores on submission to authority and conventionalism, willingness to protest, subtle prejudices, as well as on all the three dimensions on conservative values to those people who support discriminatory policies. Instead, these two groups differ as concerns more overtly hostile attitudes, such as authoritarian aggression and blatant prejudices and social dominance orientation. Finally, as concerns moral exclusion attitudes, as hypothesized indifferent people are less inclusive than those who oppose restrictions of human rights, even if they have higher scores of inclusion compared to those who openly approve such rights restrictions.

These data suggest that people who assume a position of indifference towards other social groups whose rights are threatened by authority may have a role in supporting such arbitrary policies akin to those people who more directly obey and support them. Indeed, even if they are less overtly aggressive and exclusive, their non-positioning towards authority's policies is based on attitudes of submission to authority and conformism as well as on subtle forms of prejudice. In this last case, as confirmed by data on modern racism as well, indifferent people have indeed higher scores as compared to opponents. This is in line with studies on the holocaust (e.g. Bauman, 1989; Staub, 2014) as well as those analyzing the more recent intergroup clashes characterizing our contemporary societies (e.g. Bar-On, 2001). That is, the role of the "silent" population before discriminatory laws and actions has a relevant function in supporting or, instead, opposing such policies.

As concerns the implications of the present research, results suggest that future research should consider that inter-group dynamics do not involve just those people who obey or disobey authority. People who apparently do not take up any stance before an authority's policies must be considered as well. Indeed, as some authors (e.g. Bar-On, 2001; Verdeja, 2012) suggested, this selected indifference has an essential key role in the assent and support for these policies and in reducing opposition towards them. That is, intergroup indifference is a contributing factor because this silent stance is in some ways absorbed by the supporting and not by the opposing voices. In an analysis of mass violence, Verdeja (2012) observed that bystanders and indifferent people not taking a stance enter into a complicity with the dominant members in a society. Thus, it may be interesting to reread the research on intergroup dynamics in the light of the view of intergroup indifference as a social determinant of such dynamics. The literature has indeed mainly focused on the effects of obedience and disobedience to authority. Given the general increase in indifference towards politics and policies (see Cook & Gronke, 2005), indifference will probably have a gradually major role in all those dynamics that affect inter-group relationships. Moreover, if bystander indifference has mainly been analysed within totalitarian political systems, it may also be relevant to analyse the effects of indifference in apparently democratic societies (Johnston, 2013).

It is interesting to note that participants who are characterized by more indifferent responses to the parliamentary bills are younger than the others. This result is in line with those studies (e.g. Cartocci, 2002; Marien & Hooghe, 2011, for the Italian situation, see) that underlines that youngsters have low levels of interest in political issues. This apathy may have the consequence of increasing levels of indifference towards all the things that concern politics, including policies that affect minority and disadvantaged groups. Future studies should analyze whether indifference in youngsters is actually based on a general uninterest in political institutions and whether such apathy may have an impact on intergroup relationships and tolerance towards minorities groups.

In future studies, other socio-psychological variables may be considered in relation to intergroup indifference. In particular, the indifference and carelessness of others should be analyzed in relation to lack perception of responsibility and to the so-called "diffusion of responsibility" effect. As identified in the classical experiment of Darley and Latane (1968) on good Samaritanism, bystander intervention in emergencies often fails to materialize because people think others will intervene. This effect is probably relevant in analyzing the intergroup indifference studied in the present research as well. That is, this type of indifference might be connected to the issue that people sometimes think that others (and not themselves) have the responsibility for intervening to resolve other social groups' problems.

This research has some limitations which should be borne in mind for future research. First, other methods to distinguish indifferent people should be considered in order to improve the understanding of such individuals and the analysis of the socio-psychological variables that characterize them. Second, future studies should consider different social groups as targets of indifference in order to see whether intergroup indifference is selective (that is, just directed towards a few social groups and not others) or unselective. Moreover, it may be interesting to see whether intergroup indifference may shift into a more explicit aggression towards outgroups due to the perception of them as a threat (Brewer, 1999). Furthermore, given the role of media in fostering a climate of fear (see Passini & Battistelli, 2014), it may be relevant to analyze the impact of trust in media information on enhancing intergroup indifference. Finally, it may be relevant to consider behavioral measures of intergroup indifference to analyze whether indifferent people are less prompt to act towards some social groups. This may allow us to go beyond attitudinal measures.

Notas

1For more information see http://edition.cnn.com/2013/12/18/world/europe/italy-migrants-lampedusa, retrieved April 10, 2016.

2See http://www.corriere.it/cronache/11_giugno_05/magris-indifferenza-per-sciagure-migranti_45b53fe0-8f82-11e0-a515-0265176cef92.shtml, retrieved April 10, 2016.

3The item "We have to be tolerant toward protesters" was excluded because of an increment of Cronbach's reliability.

REFERENCES

Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Cambridge, MA: Addison-Wesley. [ Links ]

Altemeyer, B. (1996). The authoritarian specter. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Arendt, H. (1963). Eichmann in jerusalem. New York: Viking. [ Links ]

Bar-On, D. (2001). The bystander in relation to the victim and the perpetrator: Today and during the holocaust. Social Justice Research, 14(2), 125-148. [ Links ]

Bauman, Z. (1989). Modernity and the holocaust. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. [ Links ]

Brewer, M. (1999). The psychology of prejudice: Ingroup love and outgroup hate? Journal of Social Issues, 55(3), 429-444. [ Links ]

Cartocci, R. (2002). Diventare grandi in tempi di cinismo: Identita nazionale, memoria collettiva efiducia nelle istituzioni tra i giovani italiani. Bologna: Il Mulino. [ Links ]

Cook, T. E., & Gronke, P. (2005). The skeptical american: Revisiting the meanings of trust in government and confidence in institutions. Journal of Politics, 67, 784-803. [ Links ]

Corning, A. F., & Myers, D. J. (2002). Individual orientation toward engagement in social action. Political Psychology, 23, 703-729. [ Links ]

Costello, K., & Hodson, G. (2011). Social dominance-based threat reactions to immigrants in need of assistance. European Journal of Social Psychology, 41, 220-231. [ Links ]

Darley, J. M., & Latane, B. (1968). Bystander intervention in emergencies: Diffusion of responsibility. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 8, 377-383. [ Links ]

Dovidio, J. F., & Gaertner, S. L. (2004). Advances in experimental social psychology. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Aversive racism (Vol. 36, p. 1-52). New York: Elsevier. [ Links ]

Duriez, B., & Van Hiel, A. (2002). The march of modern fascism. a comparison of social dominance orientation and authoritarianism. Personality and Individual Differences, 32, 1199-1213. [ Links ]

Ellemers, N., & Barreto, M. (2009). Collective action in modern times: How modern expressions of prejudice prevent collective action. Journal of Social Issues, 65, 749-768. [ Links ]

Johnston, R. N. (2013). Building a theory of the nonindigenous canadian bystander: A multidisciplinary review of research on bystanders to genocide. In C. Kawalilak & J. Groen (Eds.), 32nd national conference ofthe canadian association for the study of adult education (p. 249-256). Calgary: University of Calgary. [ Links ]

Knafo, A., Sagiv, L., & Roccas, S. (2011). The value of values in cross-cultural research: A special issue in honor of shalom schwartz. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 42, 178-185. [ Links ]

Kteily, N. S., Sidanius, J., & Levin, S. (2011). Social dominance orientation: Cause or 'mere effect'? evidence for sdo as a causal predictor of prejudice and discrimination against ethnic and racial outgroups. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47(208-214). [ Links ]

Marien, S., & Hooghe, M. (2011). Does political trust matter? an empirical investigation into the relation between political trust and support for law compliance. European Journal of Political Research, 50, 267-291. [ Links ]

Milgram, S. (1974). Obedience to authority: An experimental view. New York: Harper & Row. [ Links ]

Monroe, K. R. (2008). Cracking the code of genocide: The moral psychology of rescuers, bystanders, and nazis during the holocaust. Political Psychology, 29(5), 699-736. [ Links ]

Opotow, S. (1990). Moral exclusion and injustice: An introduction. Journal of Social Issues, 46, 1-20. [ Links ]

Passini, S. (2008). Exploring the multidimensional facets of authoritarianism: Authoritarian aggression and social dominance orientation. Swiss Journal ofPsychology, 67, 51-60. [ Links ]

Passini, S. (2011). Individual responsibilities and moral inclusion in an age of rights. Culture & Psychology, 17, 281-296. [ Links ]

Passini, S., & Battistelli, P. (2014). Support to military or humanitarian counterterrorism interventions: The effect of interpersonal and intergroup attitudes. International Journal ofPsychological Research, 7(1), 23-33. [ Links ]

Passini, S., & Morselli, D. (2009). Authority relationships between obedience and disobedience. New Ideas in Psychology, 27, 96-106. [ Links ]

Passini, S., & Morselli, D. (2015). Supporting protest movements: The effect of the legitimacy of the claims. International Journal of Psychological Research, 8(2), 10-22. [ Links ]

Passini, S., & Morselli, D. (2016a). Blatant domination and subtle exclusion: The mediation of moral inclusion on the relationship between social dominance orientation and prejudice. Personality and Individual Differences, 89, 182-186. [ Links ]

Passini, S., & Morselli, D. (2016b). Construction and validation of the moral inclusion/exclusion of other groups (mieg) scale. Social Indicators Research, in press. [ Links ]

Pettigrew, T. F., & Meertens, R. W. (1995). Subtle and blatant prejudice in western europe. European Journal of Social Psychology, 25, 57-75. [ Links ]

Pratto, F., Henkel, K. E., & Lee, I. C. (2013). Stereotypes and prejudice from an intergroup relations perspective. In C. Stangor & C. S. Crandall (Eds.), Stereotyping and prejudice (p. 151-180). New York: Taylor and Francis. [ Links ]

Pratto, F., Sidanius, J., Stallworth, L. M., & Malle, B. F. (1994). Social dominance orientation: A personality variable predicting social and political attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 741-763. [ Links ]

Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (p. 1-65). San Diego: Academic Press. [ Links ]

Schwartz, S. H., Melech, G., Lehmann, A., Burgess, S., Harris, M., & Owens, V. (2001). Extending the cross-cultural validity of the basic human values with a different method of measurement. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 32, 519-542. [ Links ]

Solimene, M. (2011). These romanians have ruined italy'. xoraxane roma, romanian roma and rome. Journal of Modern Italian Studies, 16, 637-651. [ Links ]

Staub, E. (2014). Obeying, joining, following, resisting, and other processes in the milgram studies, and in the holocaust and other genocides: Situations, personality, and bystanders. Journal of Social Issues, 70(3), 501-514. [ Links ]

Stichweh, R. (1997). Thestranger: On the sociology of the indifference. Thesis Eleven, 51, 1-16. [ Links ]

Verdeja, E. (2012). Moral bystanders and mass violence. In A. Jones (Ed.), New directions in genocide research (p. 153-168). New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Wohl, M. J. A., & Branscombe, N. R. (2009). Group threat, collective angst, and ingroup forgiveness for the war in iraq. Political Psychology, 30, 193-217. [ Links ]

Zamperini, A. (2013). Banalita dell'indifferenza. ambivalenza di un sentimento (non sempre) al servizio del male [the banality of indifference. ambivalence of a feeling (not always) at the service of evil]. Psicoterapia e Scienze Umane, 47, 349-368. [ Links ]