1. Introduction

The concern for adolescent health has been addressed interdisciplinarily, considering unhealthy lifestyle habits a source of risk (Chen, Wang, Yang, & Liou, 2003). However, the gaze still focuses mainly on physical health (Gortmaker, Walker, Weitzman, & Sobol, 1990; Goodman, 1999; Moor et al., 2014; Ames, Leadbeater, & MacDonald, 2018), and it does not acknowledge aspects of the emotional, personal and contextual order that could constitute together psychosocial risk factors.

One of these factors is suicidal risk (Lewinsohn, Rohde, & Seeley, 1994; Gould, Fisher, Parides, Flory, & Shaffer, 1996; Nock et al., 2013; Luby, Whalen, Tillman, & Barch, 2019), which is associated in an important way to the presence of depressive symptoms, bullying and participation of interactive social networks (Urrego Betancourt, Quintero, & Manrique, 2016; Klomek et al., 2013; Sourander et al., 2010; Marini, Dane, Bosacki, & Cura, 2006; Lewinsohn, Rohde, & Seeley, 1998; Lewinsohn, Roberts, Seeley, Rohde, & Et, 1994; Harter, Marold, & Whitesell, 1992; Grover & Avasthi, 2019).

In the health of the adolescent, there is increasing concern on their self-care practices and the emotional difficulties that accompany this stage (Abraham, Lee, Nelson, Yue, & Chow, 2015; Walker et al., 2002; Trinidad, Unger, Chou, & Anderson, 2004; Crockett, Carlo, Wolff, & Hope, 2016), as well as the interest in reducing dependency on parents and strengthening attachment with peers (Franz & White, 1985; Kidwell, Dunham, Bacho, Pastorino, & Portes, 1995; Wim & Inge, 2010; Urrego Betancourt et al., 2014; Cui, Graber, Metz, & Darling, 2019).

The promotion of health in this population has focused on self-care practices in physical health (Brenda & Barbara, 2006; Mohamadian, Eftekhar Ardebili, Rahimi Foroushani, Taghdisi, & Shojaiezade, 2011). However, as Pender (1996) points out, it includes cognition and social support (Wu, Pender, & Noureddine, 2015). In addition, several investigations highlight the role played by the family in both health and risk prevention (Cuffe, McKeown, Addy, & Garrison, 2005; Fatori, Bordin, Curto, & De Paula, 2013; Ellis et al., 2017).

In the present investigation, the well-being and the psychosocial risk are considered, starting from the social cognition, a mediator in the social functioning that includes two essential components: empathy, according to Eisenberg (2000), is an emotional response that comes from understanding the state or situation of another person and is similar to what the other person is feeling; and the Theory of Mind (ToM), specified by Taylor (1998, 2006)Taylor (1998, 2006) as the inference of cognitive, motivational and affective states in others. In this regard, recent research in adolescence and young adulthood highlight the role of empathy in the processes of social interaction (Grant, 2014; Wagaman, Geiger, Shockley, & Segal, 2015; Van der Graaff, Carlo, Crocetti, Koot, & Branje, 2018), as well as the role of context on its modulation and its contribution to increase psychological well-being (Coutinho, Silva, & Decety, 2014; Melloni, Lopez, & Ibanez, 2014; Wondra & Ellsworth, 2015).

It also included the perception of social support (Tardy, 2006), understood as the provision or possibility of receiving support from the network, even if it is not being used (in Barrón, 1996), which has been included as an intervening factor in the promotion of health and prevention of disease (Rodrigo & Byrne, 2011; Bekele et al., 2013; Cheng et al., 2014; Greco et al., 2014; Kwan & Gordon, 2016).

Additionally, the perception of the quality of intrafamiliar relationships (Rivera-Heredia & Andrade, 2010), along with the attachment, defined as one bond that is formed between itself and another, a bond that joins them in space and that lasts over time (Bowlby, 1969/1982, 1998; Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978), contribute into formal education contexts to the promotion of well-being in children and adolescents (Everri, Mancini, & Fruggeri, 2015; Leme, Del, & Coimbra, 2015; Liang, Lund, Mousseau, & Spencer, 2016).

Another of the study variables was emotional selfregulation, given the challenges it represents in this stage of life and its importance in the prevention of suicide (Weinberg & Klonsky, 2009; Crockett et al., 2016; Bottoms, 2013). Even more, as Gross and Thompson (2017) points out, it refers to how intrinsically each individual manages, expresses and experiences their emotions when they introduce themselves.

All these variables were studied for their explanatory value in the promotion of well-being from the perspective of eudaimonia, which states that human beings seek to live their lives the best possible way, based on their individual perspective to do it. This was proposed by Aristotle in Ethics to Nicomaco (cited by Ryff, 1989; Ryff & Keyes, 1995; Waterman, 1990). In 1989, Carol Ryff takes and theoretically structures this perspective, considering different approaches together to positive functioning in psychology: Erikson’s stages of psychosocial development (1959, 1994), Neugarten’s continuous growth (1973), the descriptions of well-being of clinical psychology from Maslow’s conceptualization (1968), Allport’s formulation of maturity (1961), and Rogers’s full personal functioning (1974). As a result, Ryff (1989); Ryff and Keyes (1995); Ryff and Singer (2013); Ryff et al. (2016) proposes that psychological well-being consists of the dimensions of self-acceptance, self-realization, autonomy, personal growth, quality of relationships and control of the environment. This, in turn, is conceptually related to the motivational theoretical formulation of the organismic metatheory on self-determination posed by Deci and Ryan (1987).

Table 1 Evaluation instruments. Measurements of internal consistency, average expected, mean and standard deviation obtained

| Model participation | Variable | Instrument | Dimensions | Cronbach Alpha | Expected Mean(Obtained in validation) | Standard validation deviation | Obtained mean | Standard deviation obtained | |

| Predictive variables | Empathy | Inter-personal Reactivity | Fantasy | .73 | 14.91. | 5.32 | 14.44 | 4.05 | |

| Predictive variables | Empathy | Index (Davis et al., 1980) | Perspective take | .64 | 15.32 | 4.27 | 13.36 | 4.70 | |

| Predictive variables | Empathy | in the adapted and validated | Empahy concern | .60 | 18.25 | 4.37 | 8.99 | 2.96 | |

| Predictive variables | Empathy | versión by Mestre Escrivá, Frías Navarro, and Samper García (2006) | Personal discomfort | .65 | 11.37 | 4.59 | 12.84 | 3.96 | |

| Predictive variables | Theory of the mind | Eyes test of Baron-cohen (2001), from the validation carried out in Argentina by Roman et al. (2012) | Total Theory of the mind (Inference of cognitive and emotional states in others) | .61 | 23.36 | 4.87 | 19.06 | 3.79 | |

| Predictive variables | Quality of intra-familiar relationships | ERI Evaluation scales of intra-familiar relationships (Rivera-Heredia & Andrade, 2010) | Unity and support | 0.92 | Scales: High: 5547 | 29.98 | 8.27 | ||

| Medium high: 46 38 | |||||||||

| Median: 37 29 | |||||||||

| Medium Low: 28 20 | |||||||||

| Low: 19 11 | |||||||||

| Predictive variables | Expression | 0.90 | Scales: High: 11094 | 55.14 | 13.57 | ||||

| Medium high: 9377 | |||||||||

| Median: 76 56 | |||||||||

| Medium Low: 55 39 | |||||||||

| Low: 3822 | |||||||||

| Predictive variables | Difficulties | 0.87 | Scales: High: 11598 | 55.02 | 11.54 | ||||

| Predictive variables | Medium high: 97 80 | ||||||||

| Predictive variables | Median 79 59 | ||||||||

| Predictive variables | Medium low: 58 41 | ||||||||

| Low: 40 23 | |||||||||

| Predictive variables | Social support perceived | Colombian adaptation of | Emotional/ informational | .88 | 32.8 | 6.6 | 30.0 | ||

| Predictive variables | the Medical Outcomes Study Social | support Instrumental | .60 | 16.6 | 3.4 | 15.14 | |||

| Predictive variables | Support Survey MOS of | support Positive social | .84 | 16.5 | 3.3 | 16.07 | 6.99 | ||

| Predictive variables | (Sherbourne & Stewart, 1991), validated by N. E. Londoño et al. (2012) | intection Total-Social support perceived | 0.93 | Medium Punctuation expected: 57 | 73.86 | 14.83 | 3.31 | ||

| Predictive variables | Affective bond attachment | Colombian adaptation and Validation of the Questionnaire | Attachment-Parents: Trust and communication | .93 | Medium Punctuation expected:40 | 52.26 | 10.26 | 3.58 | |

| Predictive variables | “People in my life” (Cook, Greenberg, & Kusche, 1995), by Camargo, Mejía | Attachment Peers: Trust and communication | .88 | Medium Punctuation expected:40 | 47.49 | 11.37 | |||

| Predictive variables | Herrera, and Carrillo (2007) | Attachment-Teachers and school affiliation | .88 | Medium Punctuation expected:37.5 | 40.49 | 9.17 | |||

| Predictive variables | Camargo, Mejía, Herrera, and Carrillo (2007) | AttachmentNeighbourhood-Positive | .70 | Medium Punctuation expected:6 | 7.58 | 2.29 | |||

| Predictive variables | by Camargo, Mejía, Herrera, and Carrillo (2007) | Attachment-Neighbourhood-Danger | .69 | Medium Punctuation expected:10 | 8.03 | 3.02 | |||

| Predictive variables | Camargo, Mejía, Herrera, and Carrillo (2007) | Attachment-Alienation | .74 | Medium Punctuation expected:35 | 31.01 | 6.92 | |||

| Predictive variables | Emotional regulation | Sacle of emotional selfregulation (Cortés, Cuellar, González, & Gualteros, 2016) | Attention and emotional recognition | .62 | 8.83 | ||||

| Predictive variables | Emotional self-regulation in the social field | .61 | 5.39 | ||||||

| Predictive variables | Emotional regulation strategies | .60 | 5.39 | 1.84 | |||||

| Predictive variables | Adaptation to new and complex situations | .60 | 8.61 | 1.46 | |||||

| Predictive variables | Total-Emotional regulation | .74 | 29.76 | 1.46 | |||||

| Criteria Variables | Suicide risk | Test of characterization of suicide risk | Cognitive factors | .98 | 23.00 | 1.84 | |||

| Criteria Variables | (Urrego Betancourt et al., 2016) | Emotional factors | .91 | 17.84 | 6.36 | ||||

| Criteria Variables | implemented in Cortés et al. (2016) | Behavioral factors | .92 | 19.94 | 13.93 | ||||

| Criteria Variables | Psychosocial risk | instrument to identify psychosocial | Ability to identify family ties | .61 | 29.35 | 7.98 | |||

| Criteria Variables | risk factors associated with child suicide | Ability to identify physical abuse | .78 | 20.45 | 11.08 | ||||

| Criteria Variables | Ability to identify psychological abuse | .81 | 7.39 | 4.79 | |||||

| Criteria Variables | (Lalinde, Rey, Ramirez, Laguna, & Rodriguez 2012) | Ability to identify academic pressure | .80 | 15.67 | 5.92 | ||||

| Criteria Variables | Perception of psychological well-being | Adaptation to the Psychological | Self-acceptance | 0.69 | Medium Punctuation expected:21 | 23.87 | 5.92 | 3.16 | |

| Criteria Variables | Well-being Test by | Positive relationships | 0.63 | Medium Punctuation expected:21 | 24.63 | 5.12 | 5.35 | ||

| Ryff and Keyes (1995), conducted by | Autonomy | 0.62 | Medium Punctuation expected:28 | 30.50 | 5.81 | ||||

| Díaz et al. (2006) and validated in | Domain of the environment | 0.60 | Medium Punctuation expected:21 | 24.81 | 4.53 | ||||

| Colombia by Pineda-Roa, Castro-Muñoz, A., and Chaparro-Clavijo (2018) | Personal growth | 0.70 | Medium Punctuation expected:14 | 18.00 | 3.89 | ||||

| Purpose in life | 0.72 | Medium Punctuation expected:21 | 25.19 | 5.79 | |||||

Tabla 2 Complete matrix of correlations with Spearman’s rh o

| Correlations | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 | |

| 1. Empathy-Perspective shot | .377** | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2. Empathy-Fantasy | .304** | .524** | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3. Empathy empathic concern | .229** | .504** | .414** | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4. Empathy Upset Staff | .655** | .844** | .720** | .729** | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5. Total Empathy | .185* | 0.139 | 0.154 | 0.057 | .179* | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6. Total Empathy Tom | .155 | .62* | .05 | .063 | 0.111 | .076 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7. Union and support | .63* | .067 | .017 | .056 | 0.06 | .088 | .873** | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8. Expression | .094 | .000 | .127 | .296** | 0.101 | .074 | .620** | .636** | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9. Difficulties | 0.128 | .189* | .088 | .110 | .181* | .079 | .322** | .337** | .315** | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10. Informational emotional support | .148 | 0.134 | .034 | 0.092 | 0.128 | 0.057 | .161* | .233** | .201* | .599** | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11. Instrumental support | .119 | .142 | .034 | .100 | .142 | .035 | .209** | .279** | .235** | .774** | .671** | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12. Positive social interaction | .145 | .177* | 0.039 | 0.113 | .170* | 0.072 | .273** | .329** | .287** | .926** | .799** | .907** | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13. Total Social support | .154 | .155 | .010 | .102 | .148 | .149 | .105 | .135 | .116 | .382** | .166* | .274** | .350** | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 14. Parents attachment-Confidence and communication | .234** | .220** | .119 | .243** | .283** | 0.110 | .12 | .028 | .124 | .280** | .113 | .280** | .271** | .503** | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15. Pairs attachment-Confidence and communication | .258** | .285** | .105 | .283** | .328** | .039 | .006 | .001 | .027 | .225** | .113 | .193* | .212** | .311** | .576** | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 16. Teacher and school attachment-Membership | .260** | .248** | .064 | .238** | .288** | .033 | .137 | .134 | .082 | .212** | .117 | .200* | .201* | .304** | .327** | .637** | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 17. Attachment neighborhood-Positive | .087 | .146 | .30 | .048 | .139 | 0.41 | .175* | .156 | .076 | .053 | .169* | 0.33 | 0.65 | .134 | .132 | .175* | .141 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 18. Attachment neighborhood-Danger | .133 | .254** | .129 | .211** | .254** | .131 | .010 | .039 | .082 | .047 | .019 | .014 | .028 | .073 | .013 | .202* | .267** | .592** | ||||||||||||||||||

| 19. Attachment-Alienation | .016 | .099 | .043 | .003 | .034 | .050 | .000 | .071 | .044 | .233** | .308** | .238** | .283** | .061 | .149 | .087 | .111 | .100 | .035 | |||||||||||||||||

| 20. Attention and emotional recognition | 0.73 | .258** | .177* | .303** | .278** | .050 | .007 | .104 | .012 | .369** | .268** | .302** | .358** | .253** | .285** | .377** | .358** | .057 | .080 | .235** | ||||||||||||||||

| 21. Emotional self-regulation in the social field | .006 | .115 | .145 | .057 | .027 | .104 | .093 | .134 | .105 | .228** | .264** | .234** | .263** | .127 | .193* | .308** | .207** | .172* | .098 | .228** | .481** | |||||||||||||||

| 22. Emotional self-regulation strategies | .222** | .139 | .069 | .094 | .148 | .123 | .199* | .207** | .190* | .402** | .286** | .369** | .414** | .281** | .249** | .316** | .304** | .023 | .048 | .189* | .333** | .325** | ||||||||||||||

| 23. Adaptation to new and complex situations | .453** | .063** | .423** | .550** | .696** | .077 | .056 | .32 | .175* | .006 | .099 | .109 | .095 | .082 | .281** | .274** | .260** | .067 | .305** | .114 | .140 | .159* | .255** | |||||||||||||

| 24. Total emotional regulation | .111 | .002 | .020 | .014 | .050 | .125 | .091 | .108 | .210** | .123 | .081 | .187* | .140 | .253** | .004 | .086 | .095 | .082 | .156 | .002 | .031 | .080 | .171* | .066 | ||||||||||||

| 25. Suicide Risk-Cognitive | .150 | .006 | .009 | .005 | .054 | .119 | .179* | .174* | .276* | .157 | .072 | .175* | .155 | .253** | .077 | .142 | .120 | .131 | .144 | .032 | .046 | .029 | .162* | .117 | .928** | |||||||||||

| 26. Suicide Risk-Emotional | .166* | .029 | .019 | .030 | .031 | .137 | .019 | .002 | .0157 | .058 | .020 | .156 | .073 | .181* | 008 | .032 | .115 | .021 | .122 | .043 | .008 | .079 | .091 | .022 | .881** | .819** | ||||||||||

| 27. Suicide Risk-MOTOR | .002 | .027 | .094 | .043 | .001 | .034 | .262** | .258** | .205* | .397** | .184* | .257** | .338** | .554** | .222** | .177* | .147 | .089 | .018 | .098 | .173* | .112 | .117 | .008 | .104 | .171* | .035 | |||||||||

| 28. Psychosocial risk-family bonding | .110 | .200* | .178* | .258** | .252** | .078 | .036 | .122 | .135 | .147 | .084 | .081 | .136 | .357** | .146 | .039 | .107 | .379** | .424** | .002 | .007 | 030 | .114 | .212** | .090 | .073 | .071 | .052 | ||||||||

| 29. Psychosocial risk-Physical abuse | .078 | .138 | .150 | .091 | .152 | .168* | .036 | .125 | .040 | .212** | .090 | .116 | .177* | 432** | .229** | .060 | .122 | .326** | .294** | .075 | .059 | .011 | .067 | .188* | .125 | .122 | .108 | .149 | .715** | |||||||

| 30. Psychosocial risk-Psychological abuse | .039 | .135 | .135 | .187* | .167* | .213** | .011 | .053 | .068 | .071 | .044 | .086 | .092 | .0186* | .219** | .078 | .160* | .435** | .578** | .083 | .078 | .060 | .150 | .144 | .041 | .052 | .015 | .097 | .650** | .502** | ||||||

| 31. Psychosocial risk-Academic pressure | .094 | .053 | .035 | .022 | .056 | .057 | .056 | .034 | .043 | .157 | .093 | .189* | .176* | .231** | .208** | .179* | .070 | .051 | .059 | .037 | .380** | .396** | .253** | .132 | .054 | .033 | .054 | .061 | .197* | .154 | .101 | |||||

| 32. Eudaimonic well-being-self-acceptance | .021 | .019 | .017 | .076 | .016 | .171* | .149 | .003 | .104 | .260** | .099 | .261** | .258** | .279** | .368** | .179* | .081 | .061 | .212** | .130 | .279** | .145 | .187* | .056 | .094 | .055 | .074 | .093 | .279** | .174* | .295** | .484** | ||||

| 33. Eudaimonic well-being-Positive Relationships | .004 | .111 | .172* | .028 | .080 | .020 | .111 | .037 | .054 | .128 | .118 | .114 | .156 | .279** | .234** | .080 | .084 | .205* | .264** | .050 | .348** | .174* | .200* | .068 | .045 | .060 | .080 | .049 | .332** | .270** | .299** | .512** | .398** | |||

| 34. Eudaimonic well-being Autonomy | .136 | .022 | .001 | .125 | .099 | .104 | .094 | .038 | .082 | .187* | .130 | .140 | .192* | .309** | .343** | .269** | .017 | .063 | .104 | .235** | .333** | .381** | .312** | .201* | .043 | .015 | .055 | .116 | .220** | .194* | .152 | .621** | .403** | .441** | ||

| 35. Eudaimonic well-being Domain of the environment | .247** | .191* | .220** | .223** | .295** | .022 | .231** | .282** | .031 | .129 | .141 | .117 | .150 | .152 | .163* | .126 | .000 | .102 | .040 | .027 | .175* | .219** | .118 | .323** | .014 | .016 | .040 | .213** | .00 | .030 | .082 | .432** | .271** | .242** | .526** | |

| 36. Eudaimonic well-being Personal growth | .236** | .250** | 0.144 | .170* | .278** | .097 | 0.135 | .181* | 0.003 | .281** | .221** | .250** | .300** | .298** | .359** | .259** | 0.081 | .127 | .076 | 0.108 | .396** | .357** | .247** | .225** | 0.028 | 0.057 | 0.041 | .207** | .170* | .195* | .130 | .643** | .381** | .462** | .678** | .625** |

| 37. Eudaimonic well-being-Life purpose | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ** The correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (bilateral). |

Additionally, the psychosocial risk was incorporated from the evaluation of the presence of environmental variables that include psychological and socioeconomic factors, such as problems related to the primary group, the social, educational environment (N. Londoño et al., 2010) and that represent difficulties and suicidal risk, characterized by beliefs linked to the end of life (Vargas & Saavedra, 2012). Thus, the question that this research sought to answer was:

Is the relationship between the perception of wellbeing and the presence of psychosocial risk of suicide significant, taking into account social cognition, the perception of the quality of social and emotional relationships, and emotional regulation?

Therefore, the objective of the research was to establish the level of each of the variables in the adolescent population and to observe if the relationships between social cognition, the perception of the quality of relationships and the emotional regulation are significant in relation to the psychosocial risk, the suicidal risk and the level of psychological well-being in adolescents in highly vulnerable contexts in Bogotá

2. Method

2.1 Investigation design

This was a quantitative methodology research, of descriptive nature, with analysis of correlational data, crosssectional and non-experimental (Hernández Sampieri, Fernández Collado, & Baptista Lucio, 2010).

2.2 Participants

A total of 155 adolescents from middle school (66 of 8th grade and 89 of 9th grade) participated, with a range of ages between 13 and 17 years (M = 14.47 and DE = 1.03), in conditions of socio-economic vulnerability, belonging to a school in the city of Bogotá, situated in the locality of Kennedy, where there are high health tensions in the adolescent population (Hospital del Sur E.S.E, 2014) and high rates of suicide (Unidad de atención del sur, 2016). Sampling was for convenience and the data from adolescents who reported suicide attempts, and those who neither themselves nor their families wanted them to participate in the study were excluded.

2.3 Instruments

The instruments are presented in Table 1, specifying the evaluated dimensions, the internal consistency levels, the expected means and the obtained means.

2.4 Procedure

The research was carried out in the five phases. First, identifying schools in localities with high socioeconomic vulnerability, with practice agreements and research with Universidad Piloto de Colombia. Secondly, obtaining institutional permits and signing consents (parents) and assents (teenagers). Thirdly, applying the instruments in two sessions, in order to avoid bias due to tiredness or social desirability, during two consecutive days. In the first one, the following were applied: the IRI, BaronCohen’s Eyes test, the ERI, the MOS, the Emotional Self-regulation questionnaire; in the second, the suicide risk, psychosocial risk and perception of well-being tests. The applications were done in five groups, according to the distribution of students in their classrooms. The instructions were read verbally as each participant selected the answers. Two formats were created to record each one of the answers through pencil and paper. 4) Obtaining data from the typing of each of the answers to a matrix designed in Excel, according to the options of each instrument. Fifthly, analyzing results through the use of SPSS software, v.24, as well as elaborating the discussion and conclusions. Statistically, descriptive analyzes were performed through measures of central tendency (mean and standard deviation expected v. Obtained, see Table 1) and non-parametric inferential analyzes of bivariate correlation type, using Spearman’s rho. Finally, linear regression analysis was carried out using the simultaneous introduction method, in which all the predictive variables are entered in order to determine those variables that best allow predicting the behavior of the research criterion variables from the level of significance (Alderete, 2006).

3. Results

The measurements of empathy and the theory of the mind ToM provided the average expected levels. There were high levels of perception of social support, quality in intra-familiar relationships, and attachment from parents and peers. High levels of emotional regulation and perception of well-being were observed. Finally, regarding the presence of psychosocial risk associated with suicide, low levels were reported.

Concerning the relationship between the variables (see Table 2), we can see the complete matrix composed by the relationships among the 37 evaluated dimensions from the nonparametric statistic of Spearman’s rho.

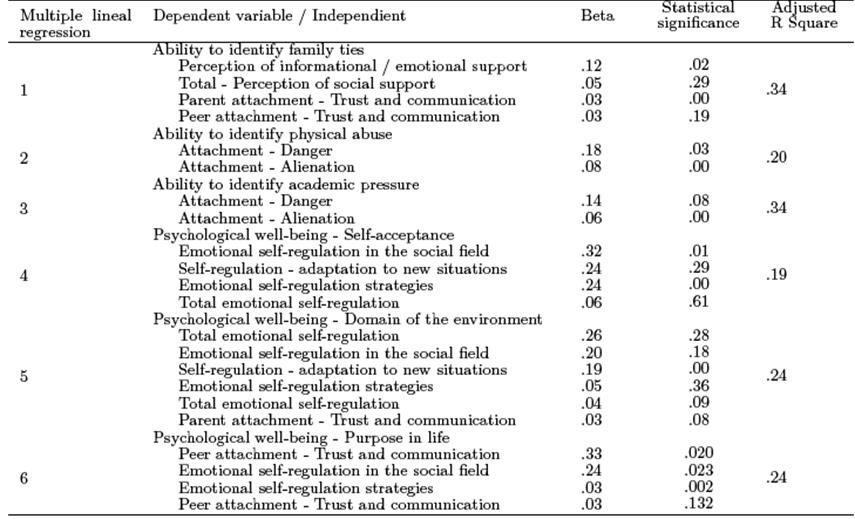

In Table 3, the significant relationships with value p < 0.01 and R equal or superior to 0.3 are highlighted. Finally, to determine the explanatory capacity of the predictive variables on the criterion variables, linear regression analyzes were performed, which are presented

in Table 4.

This analysis highlights the relationship between the perception of social support, attachment and emotional self-regulation with indicators of psychosocial risk and the perception of well-being. In addition, it is possible to identify a positive relationship between the affective bond with parents and the identification of protective factors of psychosocial risk. At the same time, there is a relationship between “Alienation”, a negative indicator of attachment, as a predictor of psychosocial risk. Finally, the indicators of the perception of well-being are affected by the strategies of emotional self-regulation and by the affective bond with parents and peers.

4. Discussion

In the study sample, the expected levels of social cognition and emotional regulation were presented. Although these levels may be influenced by the n of the sample and because only one educational institution was included, adolescents are in a stage where social relationships with their peers are important, which implies the use of skills to infer the cognitive, motivational and affective states of others (Taylor, 2006). In this regard, the capacity for mentalization helps to understand emotions and generate empathy.

Regarding the level of significance, the role of social cognition in the perception of well-being and risk prevention was reaffirmed in these findings (Melloni et al., 2014; Wondra & Ellsworth, 2015; Taylor, 2006; Davis, 2017). This relationship was only evidenced from some dimensions, especially personal growth and life purpose, and although it was significant, it was not strong. However, it can be seen in clinical implications how the role of having clear goals and generating conditions for the development of potentialities can be effective in preventing situations that lead to health deterioration. School levels and the stage of life can also explain the score, as adolescents are approaching the end of their basic cycle and bit by bit they become more reflective about their future.

The results also showed a relationship between the perception of the quality of intra-familiar relationships and the promotion of well-being, both evaluative variables on social interactions and the processes involved (Taylor, 2006; Davis, 2017).

In the same direction, but with greater strength in the association, the affective bond was related to the perception of well-being and psychosocial risk. The importance of attachment to parents and peers and their association with well-being (Urrego Betancourt et al., 2014), was confirmed. And contrary to what has been found on reducing dependence on parents (Franz & White, 1985; Kidwell et al., 1995; Wim & Inge, 2010), which the study group shows, is that the support received by parents is found to be a protective factor and an aspect to be taken into account in the caring practices and the perception in the sense of well-being. On the other hand, it is interesting to find that according to what is reported in the health indicators (Hospital del Sur E.S.E, 2014; Unidad de atención del sur, 2016), the participants’ school location presents several psychosocial risks, tensions in health and suicidal behavior. Those aspects were not evident in the sample, and that confirms once again the protective role found in other investigations of the links with parents and peers and their role in promoting well-being (Everri et al., 2015; Leme et al., 2015; Liang et al., 2016), which should be integrated into the design of effective suicide prevention and welfare promotion programs.

In the same direction, the role of emotional selfregulation was observed, although it was only linked to the perception of psychological well-being (Gross & Thompson, 2017; Crockett et al., 2016). No strong association was found to suicide risk because the results were within the expected mean. In other words, despite the fact that there was no causal relationship, a greater perception of psychosocial risk and a lower suicide risk could be established indirectly.

5. Conclusions

The results show that in adolescence, the explanatory capacity of the factors coming from affective relationships continues to be greater. (Bowlby, 1969/1982, 1998; Ainsworth et al., 1978; Liang et al., 2016; RodríguezFernández et al., 2016; Cui et al., 2019; Grover & Avasthi, 2019).

These findings, despite the limitations related to the sample size and the type of sampling, suggest that, in order to intervene, with the purpose of promoting adolescent health and wellbeing, it is important to strengthen the affective bond and the emotional self-regulation strategies as central sources, without ignoring the role of social cognition and the perception of social support in this population.

It is suggested to continue with studies that expand the sample, validate the relationship of the variables, including different sociodemographic characteristics and the protective factors found here, in the design of programs that help to reduce suicide, being a daily problem that has increased in a vertiginous way in groups of adolescents and children.