1. Introduction

Teen dating violence is a relevant public health problem associated with a wide range of negative short-term and long-term physical and psychological outcomes (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2016). The presence of conflict and violence in these initial relationships are related to a higher risk of engaging in aggressive intimate partner relationships in adulthood (MorenoManso, Blázquez-Alonso, García-Baamonde, GuerreroBarona, & Pozueco-Romero, 2014). However, adolescents’ romantic relationships differ from adult cohabiting and married intimate relationships (i.e., adolescents’ relationships tend to be more superficial, less committed, and of shorter duration) as well as in their relational patterns and expressions of violence, characterized for being moderate in severity and reciprocal (e.g Knox, Lomonaco, & Alpert, 2009). Also, it is crucial to understand that adolescents’ dating relational patterns are specific to the teenage generation of the digital era. That is, the use of the new technologies, in particular, has become part and parcel of adolescents’ and youth’s intimate relational style, even using the new technologies for perpetrating aggression toward the dating partner, especially for controlling purposes (David-Ferdon & Hertz, 2007). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2014) included the use of new technologies as a way of perpetration aggression on its definition: “Dating violence is defined as any psychological, physical, or sexual violence or stalking perpetrated by a current or former dating partner either in person or electronically.” However, the assessment of teen dating violence does not always meet this conceptualization. Besides, a very low percentage of those assessment tools provide a confirmatory study of the factor structure (López-Cepero, Rodríguez-Franco, & Rodríguez-Díaz, 2015). Therefore, it is crucial to have valid and reliable assessment instruments that capture and accurately assess the specificity and complexity of teen dating violence.

Many of the measures used to assess teen dating violence were originally developed for adults (Smith et al., 2015), including the most used scale called the Conflict Tactics Scale ([CTS] (Straus, 1979)Straus, 1979) and its different versions (e.g„ [CTS2] Straus, Hamby, BoneyMcCoy, & Sugarman, 1996; [M-CTS] Muñoz-Rivas, Andreu, Graña, O’Leary, & Gonzalez, 2007).

There are other instruments that were developed for the adolescent population. Nevertheless, some of them only measure victimization, and this does not allow us to capture the reciprocal patterns that characterize teen dating violence (Yanez-Peñúñuri, Hidalgo-Rasmussen, & Chávez-Flores, 2019). There are six measures which were developed to assess both victimization and perpetration: the Safe Dates (Foshee et al., 1996), the Conflict in Adolescent Dating Relationship Inventory ([CADRI] Wolfe, Scott, Reitzel-Jaffe, Wekerle, & Grasley, 2001), the Dating Violence Questionnaire ([CUVINO] Rodríguez-

Franco et al., 2010), the Dating Violence Questionnaire-R (Rodríguez-Díaz et al., 2017), the Psychological Dating Violence Questionnaire ([PDV-Q] Ureña, Romera, Casas, Viejo, & Ortega-Ruiz, 2015), and the Violence in Adolescent’s Dating Relationships Inventory ([VADRI] Aizpitarte et al., 2017). Of these measures, in IberoAmerica, VADRI adequately captures all the violence expressions aligned with the conceptualization of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2014), as it includes several indicators related to sexual, physical, and psychological behaviors, including also those taking place with the aid of new technologies. Also, and to the best of our knowledge, VADRI is the only existing scale that was created in combining a cross-cultural and a qualitative approach for its creation (Yanez-Peñúñuri et al., 2019). The VADRI demonstrated good psychometric properties in three different cultures and resulted in showing a unidimensional structure (Aizpitarte et al., 2017). This unidimensional structure can be due to the small sample sizes used for its validation that could not be able to detect the multiple possible factors of the VADRI. Thus, the purpose of this study was to further explore VADRI’s factorial structure and other psychometric properties in a Mexican adolescent population big sample (i.e., over 1,000), carrying out a series of analyses using two different but equivalent samples in order to get a shorter but valid and reliable form to facilitate its application in the Mexican context.

2. Method

2.1 Participants

The sample was not selected at random. However, in order to get more representativeness and heterogeneity, we chose different types of educational centers. A total amount of 1,055 Mexican students from secondary and high school (55.3%) and university (44.7%) took part. Regarding sex, 48.1% were females, and 51.9% were males. University students were undergraduates of a wide variety of levels and academic fields, while the rest of the students were attending secondary and high school. Ages ranged between 14 and 22 years (M = 17.66, SD = 1.95). Most of them were from urban areas (85.7%). Regarding dating experience, the 56.9% were currently dating someone, and the remaining 44.1% had been dating in the past. The average relationship length was 11.60 months (SD = 14.82). The inclusion criteria were to be currently dating or had been dating in the past, with a minimum relationship’ duration of one month.

2.2 Instruments

2.2.1 Demographics

Information about students’ sex, age, rural/urban area, level of education, length of the relationship, and dating status.

2.2.2 Dating Violence

Violent behaviors in adolescents’ dating relationships were assessed with the Violence in Adolescents’ Dating Relationships Inventory ([VADRI] Aizpitarte et al., 2017). This self-report questionnaire is composed of 26 items, scored on a 10-point Likert scale (1 = never, 10 = always). It includes items related to victimization and perpetration, covering different violent behaviors of different nature: sexual coercion, physical violence, and many psychological verbal and controlling behaviors. Higher scores indicate higher levels of dating violence perpetration and victimization. Content and convergent validity were provided by Aizpitarte et al. (2017).

2.3 Procedure

Firstly, we contacted the responsible authorities of the educational centers. They were informed about the aim of the study, the data collection procedures, as well as the confidentiality issues. Once the permission was obtained, the self-report questionnaire was sent online to the participating students, and they filled out the online survey in classrooms. Participants were informed about the goals of the research, their voluntary participation, as well as the confidential issues through an online form. Before starting the survey, it was included a statement to obtain the electronic informed consent by the participants. The electronic form took 20 minutes to complete. Regarding the ethical aspects, we followed the recommendations of the ethical code of the Sociedad Mexicana de Psicología (2010) to elaborate and obtain the informed consent from participants who were under 18 years old and above. We also considered the specific recommendations concerning psychological investigations for conducting online surveys (Hoerger & Currell, 2012).

2.4 Data Analysis

Following the suggestions of Neukrug and Fawcett (2014) for cross-validation procedure of scales, the total sample of 1,055 students was randomly split up into two samples (40% and 60%) with a proportional number of males and females. In order to explore the different dimensions of the VADRI-MX, we conducted a principal component analysis (PCA) first. Then, we carried out a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Before analyzing the factorial structure, we also tested whether the two samples differ or not in terms of age, sex, type of educational center, rural/urban area, and relationship’ length. No differences were found at any of the socio-demographics (all p >.05). Once the equivalency of the different samples was confirmed, we analyzed the factorial structure of the original VADRI in a large Mexican’ adolescent sample. The principal component analysis was conducted using SPSS 23.0 (Arbuckle, 2014), while for the CFA Mplus 6.0 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2010) was used. The PCA was carried out using the 40% of the sample (N = 426), while the CFA was conducted with 60% of the sample (N = 629).

A principal component analysis was conducted with the 26 items that composed the perpetration form of original VADRI. Factor rotation was carried out using oblique rotation (direct oblimin), given that we expected the factors to be correlated. The estimation method used was the unweighted least squares (ULS) due to the non-normal distribution of the data (Lorenzo-Seva, 2000). The exploratory factor analysis was carried out in several steps in order to detect items that might be poor indicators (Cabrera-Nguyen, 2010): a) items with .40 or lower communalities were eliminated; b) Cross-loading items with values .32 on at least two factors were deleted. Then, we conducted the CFA to test whether the factor structure resulting in the PCA (40% of the sample) was confirmed in the remaining 60% of the sample. MLR (Maximum Likelihood Robust) estimation method was used to account for the non-normal distribution of the data. As to evaluate the goodness of the model fit we used the comparative fit index (CFI), the TuckerLewis Index (TLI), and the root mean square of error approximation (RMSEA). CFI and TLI values over .90 are considered as being acceptable (Bentler, 1990), and RMSEA values smaller than .05 indicate a good model fit (MacCallum, Widaman, Preacher, & Hong, 2001).

3. Results

3.1 Principal Component Analysis

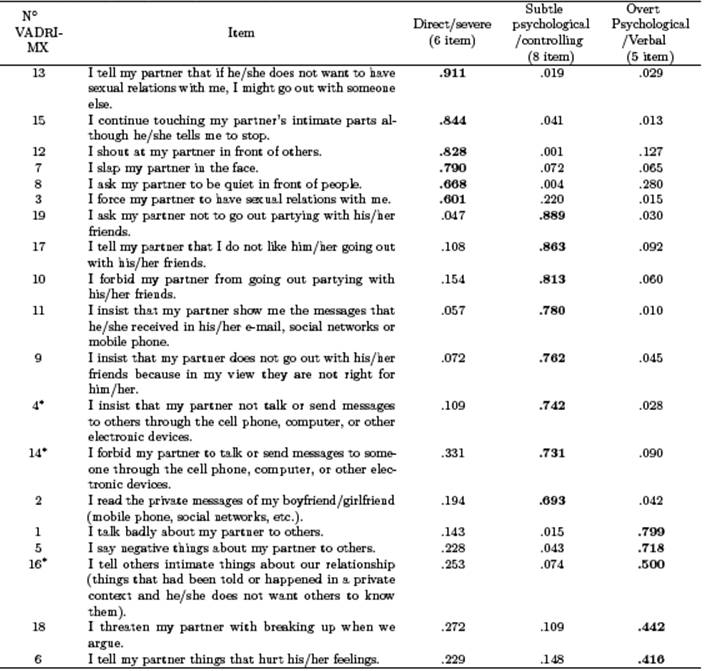

The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure confirmed that the sample size was adequate for the analyses (KMO = .92). Barlett’s test of sphericity showed that correlations between items were sufficiently large for carrying out the principal component analysis (χ 2(171) = 7.036.41, p = .000). Two items were removed because of their low communalities (less than .40), and five items were deleted due to the cross-loading criteria (values .32 on at least two factors). Therefore, a total of seven items were eliminated, and the resulting pool of 19 items was used for the subsequent analyses. The scree-plot and the eigenvalue criterion (eigenvalues over 1) suggested the presence of a three-factor solution. Thus, we conducted the subsequent analyses retaining three factors (i.e., the three-factors explained the 65.86% of the total variance). Factor 1 represents the more direct and severe behaviors of dating violence (i.e., sexual coercion, physical violence, and social humiliation). Factor 2 grouped all the controlling behaviors and isolation attempts toward the dating partner, including those behaviors displayed with the use of the new technologies. Lastly, factor 3 included several psychological violent behaviors related to verbal acts of discrediting the partner either in the partner’s presence or not. Based on the content of the items, we decided to name the three factors as it follows: 1) “Direct & severe”; 2) “Subtle psychological-controlling”; and, 3) “Overt psychological-verbal.” The variance explained for the different components were 48.95%, 12.07%, and 4.83%, respectively. Each item exhibited strong factor loadings, over .40 (Cabrera-Nguyen, 2010). For more detailed information, see Table 1.

3.2 Confirmatory Factor Analysis

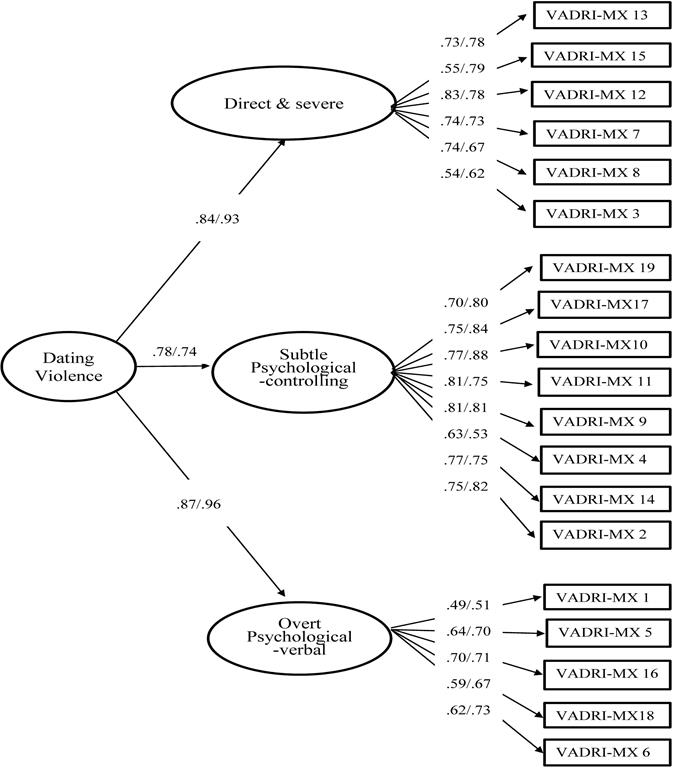

The VADRI’s three-factor structure resulted in the PCA was confirmed in the subsequent confirmatory factor analyses. Two different models were tested: a) firstorder three-factor structure; b) second-order three-factor structure. Although both models met the goodness of fit criteria, the second-order factor fitted significantly better than the first-order factor. Thus, we decided to keep the second-order three-factor structure with indices of CFI and TLI indices over .90, and RMSEA values equal or lower than .05 (CFI = .94, T LI = .93, and RMSEA = .03 for perpetration; CFI = .92, T LI = .90, and RMSEA = .05 for victimization). All the factor loadings were over .40 (See Figure 1).

3.3 Reliability Analysis

Internal consistency was evaluated to confirm the sets of items were reflecting the dating violence construct reliably. Cronbach α (Cronbach, 1951) coefficients were tested for each of the three components that composed the VADRI-MX. The Cronbach α were .92 and .94 for the total score of VADRI-MX, for perpetration and victimization, consecutively. Regarding the three factors, the α coefficients ranged between .81 and .93. More concretely, the indices for perpetration were .93, .93, and .82 for “direct & severe”, “subtle psychological-controlling”, and “overt psychological-verbal” consecutively; along with .87, .93, and .91 for victimization. All of them were above .80 as recommended by Nunnally and Bernstein (1994), indicating very good internal consistency. All the reliability indices obtained in the original VADRI (i.e., Spaniard, Mexican, and Guatemalan sample, separately) were also high (above .90).

3.4 Correspondence with the Original VADRI

The concurrent correlation was tested using the scores on the full original VADRI (i.e., one score composed of 26 items). In this manner, we analyzed the correlations between the unidimensional factor of the original VADRI full version, and the full VADRI-MX 19-item version, as well as the three factors resulted in this study (“direct & severe”, “subtle psychological-controlling”, and “overt psychological-verbal”). High correlations were found between the 26-item VADRI original version and the new VADRI-MX 19-item version (.91 for perpetration and .95 for victimization). Moderate-to-high correlations were found between the total score on the original VADRI and the three scores on the VADRI-MX for perpetration (.57 < rho > .80) and for victimization (.66 < rho > .76).

3.5 Correlations between factors

The three factors were significantly and positively correlated among each other in the whole sample. The first factor, called “direct & severe”, showed moder0ate correlations with the second factor named as “subtle psychological-controlling” for perpetration (rho =.53, p < .001) and for victimization (rho = .61, p < .001),as well as with the third factor called “overt psychologicalverbal” (rho = .66, p < .001 for perpetration and rho =.74, p < .001 for victimization). The second factor (“subtle psychological-controlling”) and the third factor (“overt psychological-verbal”) were also moderately correlated (rho = .61, p < .001 for perpetration; rho = .64, p < .001 for victimization).

4. Discussion and conclusions

The three-factor structure was found in the exploratory factor analyses and confirmed through a subsequent confirmatory study (i.e., using two different but equivalent samples randomly selected). The second-order threefactor structure fit significantly better than the firstorder three-factor structure. Thus, our findings revealed the presence of an existing underlying “dating violence” construct of the VADRI-MX, composed of three firstorder factors which include a total of 19-items. Namely, a)“direct & severe” (6 items): indicators of sexual coercion, physical violence, and social humiliation; b) “subtle psychological-controlling” (8 items): controlling behaviors and isolation attempts toward the dating partner, including the ones using new technologies; and, c) “overt psychological-verbal” (5 items): indicators of verbal acts of spreading negative things about the partner and discrediting the partner either even if the partner is present or not.

The presence of the “subtle psychological-controlling” and the “overt psychological-verbal” factors are in accordance with the scientific literature about psychological violence. Psychological violent acts are defined as communication and interaction styles based on control and domination acts, and also denigration and criticism using verbal aggression (O’Leary & Slep, 2003). In the same line, Marshall (1999) distinguished between subtle and overt ways of psychological abuse. The subtle psychological aggression is characterized by actions to controlling the dating partner, while the overt is mainly based on discrediting acts. This classification perfectly matches with the two of the three factors resulted in the factorial structure of the VADRI-MX: the one called “subtle psychological-controlling” (factor 2) and the “overt psychological-verbal” (factor 3). The most used assessment tools for adolescents (e.g., CADRI) capture several behaviors of psychological-emotional violence. However, our resultant two factors add to the dating violence measurement literature a clear distinction among two types of psychological violence: the subtlest type (i.e., completely characterized by controlling behaviors toward the dating partner) and a more overt type (i.e., related to several verbal acts aimed at hurting the partner or damaging the social image).

Regarding the controlling behaviors, which compose the “subtle psychological-controlling”, it is worth mentioning that they are not behaviors that are easily perceived by adolescents and youth as unhealthy or abusive. Even more, they can be misinterpreted by adolescents as a sign of love, affection, and interests toward the partner (Ayala, Molleda, Rodríguez-Franco, Galaz, & Díaz, 2014). This view makes these behaviors an acceptable part of dating, making them more likely to appear and maintained along with the relationship. The controlling type of behaviors, together with the verbal ones, may precede or co-occur with the most overt and severe violent behaviors (Straus et al., 1996). Besides, there is evidence pointing that the establishment of psychological violent patterns tend to be repeated along with future relationships (Lohman, Neppl, Senia, & Schofield, 2013), considering them as possible predecessors of a more severe or direct type of violent behaviors (Moreno-Manso et al., 2014).

Linked to the previous, and regarding the most severe violent behaviors, we also found a third single factor, composed of a combination of sexual, physical and social humiliation acts. Although the content of the behaviors within the factor is different (sexual, physical, and social content), what they have in common is that all of them may be considered as more direct and overt ways of violence, which may be easily recognized by adolescents as a clear expression of violence. This result may be suggesting the importance of considering some severe acts as a whole, where higher scores may be indicative of a high-risk relationship. In other words, it is more likely that the adolescents that experience sexual coercion will also be physically assaulted and may be experiencing social humiliation simultaneously.

Although the cross-sectional nature of the study did not allow us testing this prediction, we found that our first component, which includes the most severe and direct violent acts, was moderately associated with the two psychological factors. All in all, the apparition of the wide array of psychological violent may be considered as important risk factors for the apparition of other forms of severe violence, like physical violence. Thus, the indicators that composed the psychological factors of the VADRI-MX should be taken into special consideration for detecting the subtlest warning signs of dating violence (even those that take place in the aid of the new technologies) in order to reduce or stop the psychological violence and prevent the apparition of a more severe forms of violence.

The VADRI-MX showed to be a valid and reliable tool (i.e., Cronbach α indices of 82 to .94)It may be very useful for the detection of all type of dating violence behaviors, even the subtlest behaviors which may be crucial to stopping the violence cycle from continuing. Therefore, the inventory will be highly useful in different settings, such as educational, clinical and community contexts, and research. The three scores of VADRI-MX, ranging from the subtlest ones to the most direct and severe types of violence, would facilitate the detection of groups in which dating violence is more salient. This type of information may become especially important in school settings, because it would allow school agents to make decisions about implementing primary prevention programs or/and secondary prevention in highrisk groups (e.g., this would be of particular interest when we detect the presence of the violent behaviors that composed “direct & severe” component of dating violence). It will also be very helpful for practitioners and therapists when dealing with teen and young couples because it gives them information about the presence of different type of violent behaviors. This information, as well as the item-level information, would be of interest for both individual and couple therapy intervention. VADRI-MX has the strength of measuring the unidirectionality or reciprocity of the violent acts, allowing the therapist to get crucial information for applying specific strategies depending on the one-directional or mutual nature dynamics. Finally, researchers may use the VADRI-MX for several purposes: a) to examine the relationship of dating violence with several risks and protective factors; b) to examine typologies of teen dating violence; c) to analyze how the different violent behaviors are interrelated, as well as how they co-develop over time and/or along time or how may precede other more severe types of violence.

However, there are some limitations that merit attention: The sole use of self-reports for assessing dating violence, especially because of the effect that social desirability can have in the answers. The sample size for the CFA was not large enough to test the factorial structure for females and males separately. Also, regarding the concurrent correlation, we correlated the two forms of the original VADRI and the new VADRI-MX from one administration. Finally, the instrument does not consider the intent to use violence as self-defense.

Future studies should further analyze whether the three-factorial structure is maintained in different adolescent and youth populations (both clinical settings and the general population) and different cultural groups. Longitudinal analyses should be conducted to test whether the apparition of controlling and verbally abusive acts of VADRI-MX may precede the most direct and severe acts. The VADRI-MX should be implemented combined with qualitative methodology in order to better comprehend the complexity of the relationship dynamic.