1. Introduction

Emotional processes and social interactions are important units of analysis when dealing with psychological phenomena related to actors involved in contexts of political violence, since they prepare the individual to respond in an adjusted manner or not to the demands of the environment (Lynch, Trost, Salsman, & Linehan, 2007). Behavior analysis explains this set of behaviors in terms of functional relationships between such processes and context variables. Functional relationships in this sense are understood as causality relationships, in which psychological processes are maintained or modified according to the conditions of the context and alter the probability of occurrence according to their consequences (Skinner, 1975; B. P. Ballesteros & Novoa-Gomez, 2009). Contextual variables historically shape the criteria of behavior and establish what a person should or should not do at a social level (Vargas Gutiérrez & Muñoz-Martínez, 2013).

In emotional processes, repertoires are identified, such as the identification of emotional states, the communication of emotion, the ability to relate it to situations or people (Mancini, Biolcati, Agnoli, Andrei, & Trombini, 2018), and emotional regulation, aimed at modulating and responding to the own experience (Pichardo, Cano, Garzón-Umerenkova, de la Fuente, & Amate-Romera, 2018). On the other hand, behaviorism talks about social interaction as the degree to which behaviors are deployed to be competent or not in front of the demands of the social environment (Raby et al., 2018), as it is assertive communication (Boyatzis, 2018).

Evidence shows that those who grow up or are exposed to violent contexts have greater emotional difficulties and social interaction, thus perpetuating problems in groups and communities (Miller & Rasmussen, 2010; Slone & Mann, 2016; Dimitry, 2012), configuring problems of mental health and, in turn, public health (Novoa-Gomez, 2014; Larizgoitia, 2006).

Ex-combatants, victims, members of illegal armed groups and government armed forces are exposed individually or collectively to situations of risk, such as the use of weapons, massacres, kidnappings and migrations, among others. That challenges their sense of identity and meaning of life (Schweitzer, Melville, Steel, & Lacherez, 2006; Madariaga, Gallardo, Salas, & Santamaría, 2002) (Chaparro, 2009; Ojeda, 2010), generating patterns of aggressive behavior (Gallaway, Fink, Millikan, & Bell, 2012; Taft, Vogt, Marshall, Panuzio, & Niles, 2007), problems of emotional regulation (Williams, 2006), alterations in empathy (McPhedran, 2009), and deficit in the recognition of emotional expressions (Marsh et al., 2008; Petroni et al., 2011) psychological conditions that according to the systematic review conducted by Charlson et al. (2019) can evolve negatively, producing a high burden of mental disorders.

According to the available literature, the countries that have gone through these processes the most are Bosnia (Hall, Kovras, Stefanovic, & Loizides, 2018), Syria, Iraq (Svensson & Nilsson, 2018), Northern Ireland (Darby, 1995), Afghanistan, Israel, Palestine and Colombia (Fjelde & Nilsson, 2017), for conflicts that occur in political structures, social organizations and illegal armed groups in order to influence the distribution of power, authority and public resources of a society (González, 2009), compromising the psychosocial, economic and political exclusion of individuals and entire communities (Barreto, Borja, Serrano, & López-López, 2006; M. P. Ballesteros, Gaviria, & Martinez, 2006). Faced with this phenomenon, the analysis of the dynamic processes of the socio-political life of those who are immersed in violence, summons different approaches from psychology (Peña Jiménez, Quevedo Turmequé, Carreño Cáceres, & Guayan Cárdenas, 2016), since the conditions of the conflict are neither given by the behavior of a single individual, nor can their approach to traditional clinical work be circumscribed, while the study of contingencies of direct reinforcement is not possible (Glenn, 1991), which gives rise to approximations from other levels of analysis.

Faced with this, authors such as Sigrid Glenn (1988), Mark Mattaini (2004) Anthony Biglan (2009), Joao Claudio Todorov (2009) have studied societies, and have conducted research explaining the behavior of groups according to the consequences of the interlocking behavioral contingencies among the members of the group, functionally related to their social systems (economic, political and educational, among others) and their consequences at the cultural level (Glenn, 1991; Biglan, 2016; Guerin, 2006; Glenn, 2003; Malott & Glenn, 2006; Mattaini, 2004; Biglan, Flay, Embry, & Sandler, 2012). With all this and despite the fact that they outline works on this subject, the conceptual developments do not seem to be systematized. Therefore, these types of reviews are relevant, because they allow us to delimit, in a single document, the findings of various studies about this problem; to identify the possible psychological capacities that literature has to do with living in contexts of war and armed conflict; recognize the perspective of psychology against this type of phenomena; and have greater support to plant appropriate tools, whether for the construction of interdisciplinary work plans and to define the conceptual concepts that guide the opportunities of future investigations. The present qualitative systematic review seeks conceptual and methodological trends in written production, the study of emotional processes and social media in the actors involved in the contexts of political violence from the analysis of behavior.

2. Method

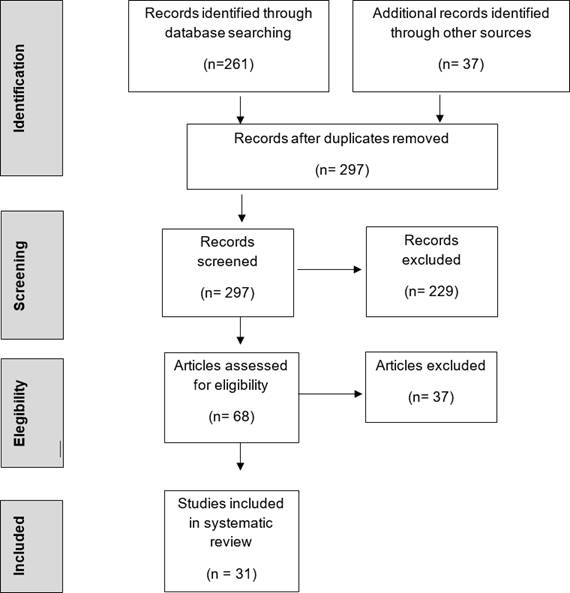

The data from this systematic review were compiled according to the revision guidelines of the PRISMA group (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, & The PRISMA Group, 2009). These guidelines allowed guaranteeing that the process was organized, strengthening the validity in the process of eligibility and replicability. Due to the novelty of the subject and the objective of the study, the date of the oldest article found (1962), until the most recent one (2018), is left as observation window.

2.1 Search strategies

The literature search was carried out from different strategies that were built independently, respecting the characteristics of each database: (1) the use of appropriate keywords that allowed greater inclusion of possible articles and (2) the application of filters allowed according to the base, in order to expand the results or delimit them, achieving greater precision in the collection of information: In SCOPUS and SPRINGER it was used: TITLE-ABS-KEY ([“Excombatants”] OR [“Victims” AND “war”] OR [“civilian population” AND “war”] OR [“Military”] OR [“civilian population” AND “political violence”] OR [“victims” AND “political violence”] OR [“Excombatants” AND “political violence”]) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ([“emotion #”] OR [“cogn”] OR [“social”] OR [“social interaction”] OR [“emotional processes”]) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ([“cultural change”] OR [“evolution”] OR [“cultural selection”] OR [“social change”] OR [“social analysis”] OR [“cultural analysis”] OR [“changing cultural practices”]) AND (LIMIT-TO [SUBJAREA,“PSYC”]) obtaining in SCOPUS a total of 53 articles and in SPRINGER within psychology and Articles, finding a total of 99 articles.

For EBSCO, the strategy was (KW [“Excombatants”] OR [“Victims” AND “war”] OR [“civilian population” AND “war”] OR [“Military”] OR [“civilian population” AND “political violence”] OR [“victims” AND “political violence”] OR [“Excombatants” AND “political violence”]) AND (AB [“motion#”] OR [“cogn#”] OR [“social”] OR [“social interaction”] OR [“emotional processes”]) AND (AB [“cultural change”] OR [“evolution”] OR [“cultural selection”] OR [“social change”] OR [“social analysis”] OR [“cultural analysis”] OR [“changing cultural practices”]) and threw a total of 19 articles.

In the case of ANNUAL REVIEW, it was used (AB [“Excombatants”] OR [“Victims” AND “war”] OR [“civilian population” AND “war”] OR [“Military”] OR [“civilian population” AND “political violence”] OR [“victims” AND “political violence”] OR [“Excombatants” AND “political violence”]) AND ([“emotion#”] OR [“cogn#”] OR [“social”] OR [“social interaction”] OR [“emotional processes”]) AND ([“cultural change”] OR [“evolution”] OR [“cultural selection”] OR [“social change”] OR [“social analysis”] OR [“cultural analysis”] OR [“changing cultural practices”]) with a total of 17 articles found.

In the case of REDALYC, it was used ([“Excombatientes”] OR [“Victimas” AND “guerra”] OR [“población civil” AND “guerra”] OR [“Militares”] OR [“población civil” AND “violencia política”] OR [“victimas” AND “violencia política”] OR [“Excombatientes” AND “violencia política”]) AND ([“emocion#”] OR [“cogn#”] OR [“social”] OR [“interacción social”] OR [“procesos emocionales”]), finding a total of 6 articles.

And finally for WEB OF SCIENCE ([Excombatants] OR [Victims AND war] OR [civilian population AND war] OR [Military] OR [civilian population AND political violence] OR [victims AND political violence] OR [Excombatants AND political violence]) AND ([emotion] OR [cogn] OR [social] OR [social interaction] OR [emotional processes]) AND ([cultural change] OR [evolution] OR [cultural selection] OR [social change] OR [social analysis] OR [cultural analysis] OR [changing cultural practices]) AND ([behaviorism] or [behavior analysis] or [contextual science] or [contextual analysis] or [functional analysis]). Refined by WEB OF SCIENCE category: (PSYCHOLOGY MULTIDISCIPLINARY OR PSYCHOLOGY CLINICAL OR PSYCHOLOGY SOCIAL OR PSYCHOLOGY OR PSYCHOLOGY APPLIED OR PSYCHOLOGY DEVELOPMENTAL OR PSYCHOLOGY EDUCATIONAL OR PSYCHOLOGY EXPERIMENTAL), obtaining 67 items.

This first compilation was completed in August 2018 and produced 261 records. Likewise, two additional sources were taken into account. First, Behavior and social issues journal, due to its expertise in dealing with social responsibility issues. It was included in the search with a total of 15 articles. Finally, the repository of the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana with the search strategy (((“Excombatants”) OR (“Victims” AND “war”) OR (“civil population” AND “war”) OR (“Military”) OR (“civilian population” AND “political violence”) OR (“victims” AND “political violence”) OR (“Excombatants” AND “political violence”) AND ((“emotion# ”) OR (“ cogn# ”) OR (“ social ”) OR (“ social interaction ”) OR (“ emotional processes ”)) AND ((“ cultural change ”) OR (“ evolution ”) OR (“ cultural selection ”) ) OR (“social change”) OR (“social analysis”) OR (“cultural analysis”))), finding 22 theses, for a total of 37 documents assumed in the category of other search sources. See Figure 1 to identify the flowchart of the search process for articles.

2.2 Inclusion criteria

After reviewing the abstracts, the documents were classified and chosen according to their relevance to the basic components of the search strategy and the criteria of the authors. Consequently, there were a total of 68 articles, with which a detailed assessment was carried out through a data extraction form developed for this review, taking into account the following inclusion criteria or subcategories: a) they should be published in English or Spanish, b) they were peer-reviewed articles and c) they responded as mentioned Urrútia and Bonfill (2010) to the criteria established for the PICOS model. This model is made up of four components that seek to have an appropriate research question. Therefore, its acronym represents the components this way: 1) Population: the participants of the articles were involved actors in contexts of political violence: ex-combatants, victims, illegal armed groups, government military forces and population civil; 2) Intervention: from the cognitive-behavioral model or behavioral analysis; 3) Comparators: were given around the variables that should handle all the articles, mainly those referring to the areas of functioning at the psychological level: the emotional processes, defined as the identification of emotional and affective states in oneself / as or in others, the communication of emotion, the ability to relate it to situations or people, and emotional regulation, and social interactions, defined as the deployment of behaviors to be competent or not in front of the demands of the environment, the effective solution of problems, assertive communication and the reduction of prejudices; and finally 4) The study design: theoretical studies, qualitative empirical studies and quantitative empirical studies.

The reviewers carefully documented the reasons for the exclusion after the full text examination and their classification was expressed as follows: “strong” referred to those articles that did not receive “negative” scores in any of the subcategories: language of publication, peer review and the 4 elements of the PICOS model previously described; qualified as “moderate” if they only had a “negative” score in one of the subcategories; and qualified as “weak” if two or more subcategories received a “negative” score. Thus, only items classified as “strong” were included in the review, leaving a total of 31 articles for analysis.

2.3 Data extraction

A worksheet was developed for the complete articles included in the review, extracting the following elements:

Characteristics of the study: database, author, affiliation of the authors, title, year of publication, journal.

Type of study: research article, theoretical article,

Keywords.

Methodology and analytical process: empirical study, qualitative study, quantitative study, interview, longitudinal study, literature review, single case study, focus group or cross-sectional study.

Main results. One author (SR) extracted the data from the fulltext articles and a second author (MN) verified the extracted data.

3. Results

3.1 Description of the articles included in the review

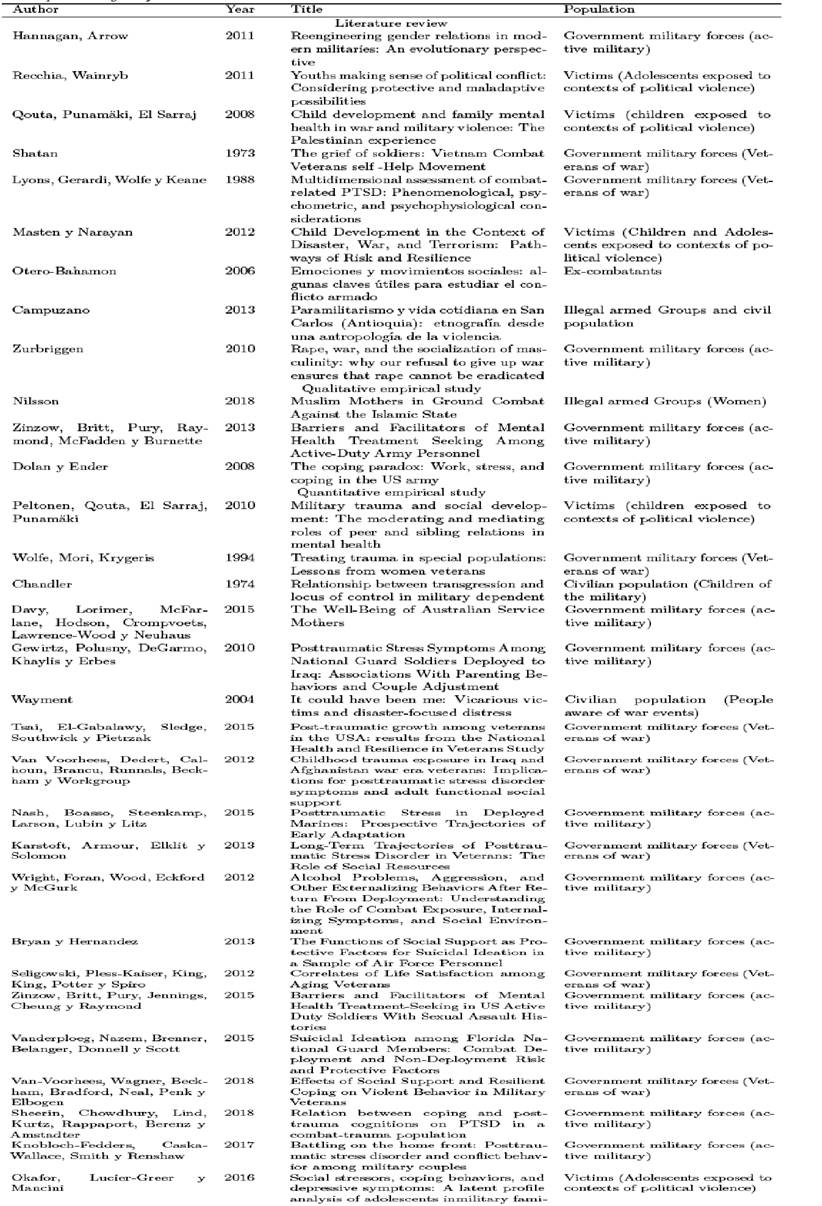

Some characteristics were analyzed in the included studies, to address conceptual and methodological tendencies in written production about the study of emotional processes and social interaction in actors involved in contexts of political violence. The descriptive analysis was carried out on elements such as (1) type of design, (2) authors of the studies, (3) dates of the intellectual production, and (4) actors of the armed conflict on which they have worked. As can be seen in Table 1, the 3 types of studies found were review of the literature (9 articles), qualitative empirical studies (3 studies), and the most frequent quantitative empirical studies (19 articles). In relation to the population, they found that the population with the most amount of work is the military forces of the government, and they divide their approach into two main categories: active members of military organizations (soldiers, members of the navy, air force and national army) with a total of 13 articles and war veterans with 8 articles. The work with victims (children and adolescents) only had 5 studies; the work with civil population, 3 articles; the approach with illegal armed groups only threw 2 articles; and the work with former combatants only showed 1 article.

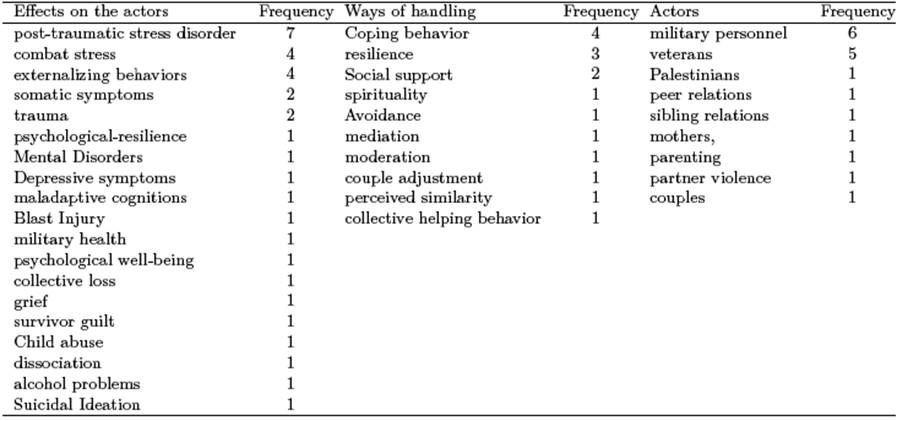

In addition, the keywords used in the articles were taken and their frequency analyzed. Finally, they were grouped into 3 main categories: (1) related to the psychological effects on the actors (2) related to coping strategies and (3) those related to the actors (See Table 2).

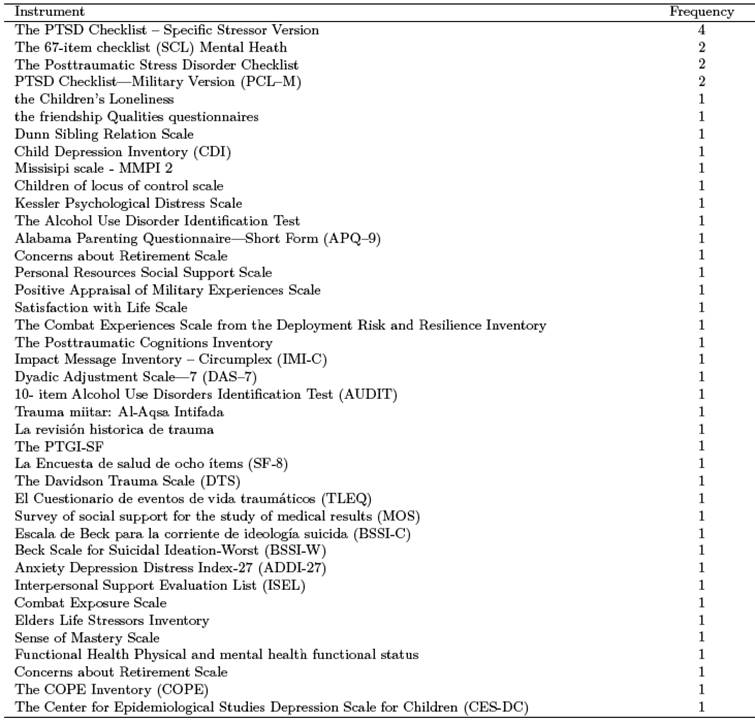

On the other hand, the frequencies of the inventories, the scales or the checklists of use in the quantitative empirical studies that are used to measure psychological variables in the actors of the study, stories such as stress, trauma, depressive symptoms, among others, will be analyzed (See Table 3).

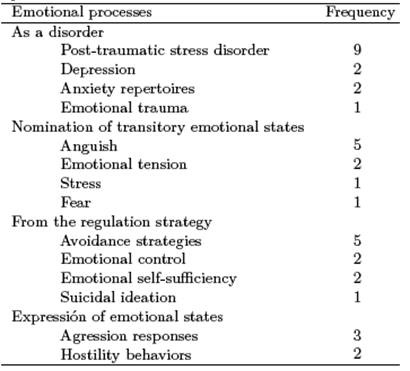

Finally, at a conceptual level, we identified the particular ways in which the authors have addressed emotional processes and social interaction, by grouping categories and frequencies in their use. The approach to emotional processes is found in Table 4, and shows that it was carried out mainly through the study of disorders with clinical conditions: post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and anxiety. On the other hand, the authors also refer to how the actors have emotional nomination processes, finding that the most frequent are anxiety and emotional tension. Emotional regulation strategies are another aspect addressed by the articles and it was found that the most reported strategies were avoidance and emotional control strategies. Likewise, forms of emotional expression are reported, with frequent responses of aggression and hostility Table 5.

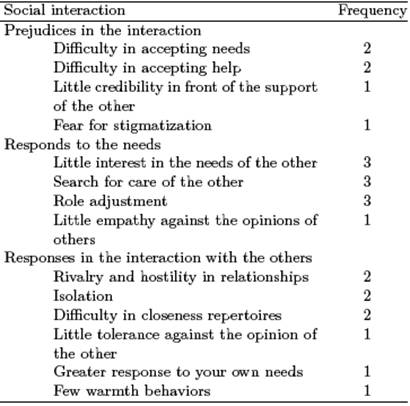

At the same time, the aspects of social interaction are reported from the prejudice, where they are characterized by the difficulty to accept their own needs and allow receiving help from others. Additionally, the answers to their own needs are null. Finally, the forms of interaction are mainly reported by hostility and isolation.

4. Discussion

Political violence has occurred from governmental military groups and illegal groups, whose actions directly or indirectly affect the civilian population and themselves, generating conditions such as forced displacement, antipersonnel mines and kidnappings, among others (VeraMárquez, Sanudo, Jariego, & Ramos, 2015; Gonzalez & Molinares, 2010), situations that modify the social, family and cultural processes of those who are victims of them. Despite having different effects in each of these populations, some common elements can be identified, since any exposure to violent events represents a risk to the mental health of those who are exposed (SchulhoferWohl & Sambanis, 2010), and although the literature offers an explanation of various consequences of exposure to violent events or contexts, perhaps one of the most prominent in the review has to do with emotional responses, characterized by emotional tension, sadness, stress and fear (Hannagan & Arrow, 2011; Recchia & Wainryb, 2011; Campuzano, 2013). In addition, characteristics that could not be communicated adequately could generate problems of interaction and closeness with others (Peltonen, Qouta, El Sarraj, & Punamäki, 2010) and, if maintained, could disqualify the subject in their interactions and make it difficult to respond to the demands of their context, affecting the normal development and the development of possible psychopaths in the future.

The results show an emphasis in the investigations on the analysis in military forces, understood as the legal institutions responsible for the territorial defense of the countries and in the war veterans (population with the highest number of studies). On the contrary, there are not enough works on other actors involved in contexts of political violence. However, this condition in the selection of the population by the researchers may be related to some factors: (a) bias towards populations that present evident levels of affectation, fulfilling the diagnostic criteria; (b) difficulty in accessing populations of illegal armed groups, which make up mobile populations, located mainly in rural areas; and (c) little openness on the part of the civilian population victim of the war, who is remaking his life in new urban areas, because the stigma diminishes the possibility of recognizing themselves as victims.

Military forces and war veterans are approached as subjects exposed to deaths, shootings, anti-personnel mines. Those are situations of high complexity that generate unsettled emotional processes, to such an extent that they are subject to diagnostic classifications and clinical disorders such as post-traumatic stress, disorders of anxiety or depression, and a greater number of interaction problems, because there are conditions in the ability to trust people, such as difficulties to establish close relationships, excessive fear of rejection and feeling of damage to their own integrity (Zinzow et al., 2013; Dolan & Ender, 2008). Throughout this analysis, diagnostic clinical categories seem to be relevant in the explanation of the difficulties of these evaluated actors. Therefore, when it comes to the question about emotional processes and social interaction researchers have opted to have an psychopathological approximation, selecting populations with marked symptoms and leaving aside in the studies populations that have also been exposed differently to the contexts of political violence, which include not only actors as guerrillas or soldiers, but peasants or civilians who are geographically close to conflict zones and, as mentioned by Sanabria and Uribe (2010), can develop psychosocial problems and inadequate long-term development, affecting both on a personal level (insensitivity to pain, impulsive patterns, difficulty in making decisions or alterations in self-esteem), as well as collective dynamics school, work and family, leaving possible areas of future work and analysis.

The results show that the most frequent studies were quantitative empirical studies, through the application of instruments and scales that provide information on constructs related to emotional states, adaptability criteria and validation of interaction problems. Despite relevant information, it does not go beyond situating specific elements of a context and a quantification of what is already known in terms of approximations and constructs (Martí, 2017). Understanding an approach from a qualitative methodology is missing in the articles reviewed and could represent a more complex analysis, based on a discursive axis and on personal experiences and their interaction stories (Mardones, Ulloa Martínez, & Salas, 2018), as well as the meanings that they give to their own experience and outline variables that define their world and how they act as a result of it (Padua, 2018).

Another relevant element in the analysis is that, in spite of having proposed words related to the behavioral and cognitive-behavioral models in the search strategies, the evaluated articles do not develop a clear epistemological stance in depth, as they only make use of cognitive terms, refer to behaviors or address them from a medical conceptualization. This tendency found in the review may be due to the difficulty involved in addressing political violence phenomena, since everything from its articulation and dynamics to its possible multiple aspects of analysis complicate the description of results, which added to the parsimony from the diagnosis in the models of psychiatric nosology, it would seem to allow results more quickly in the face of emotional expressions and interaction.

Even so, facing the analysis of the relevant variables should be supported from a clear epistemological model, since failure to do so could lead to later complications in (1) the choice of precise theories for processes of replicability and future analysis, (2) problems in the face of the possible causal relationships that the studies and the readers of the studies could reach, and (3) difficulty for the readers when taking a critical position in front of the results of each study.

With this said, and based on the variety of explanations found or the lack of them, the possibility of thinking and suggesting the approach of the phenomenon from the behavior analysis is opened, since it could bring some advantages, insofar as this position it is oriented to the construction of organized systems of empirically based concepts and rules that allow to predict and influence behavioral phenomena with precision, scope and depth (Biglan & Hayes, 1996). Dealing with this issue, psychologists such as Sigrid Glenn (1988), Mark Mattaini (2004) Anthony Biglan (2009), Joao Claudio Todorov (2009) have studied the societies and effects of cultural conflicts, recognizing a individual reality and explaining the group behavior based on the consequences of the intertwined behaviors among the members of a group.

This approach introduces the use of new concepts and new work methodologies, such as the study of metacon-tingencies, macro contingencies, culturants, the cultural lineage and macro behaviors, among others (Glenn et al., 2016). The approach mentioned has allowed some international studies on issues such as cultural change and leadership (Malott, 2016), analysis of violence (Mattaini, 2010; Todorov, 2013), and the study of situations of social exclusion (Ngoc & Guerin, 2017), among others. Thus, constituting studies that can help to propose future research on the emotional processes and social interaction in the actors involved in contexts of political violence, where the study of the behavior of several people can be incorporated on social systems; emphasizing the importance of the role of the environment for the maintenance and construction of behaviors and social interaction and identification, expression and emotional regulation; studying the basic elements of the reinforcement contingencies of these groups and the need for the empirical specification against the results of cultural practices (Glenn, 1991, 1988). As a result, it contributed to qualitative research designs through tools such as in-depth interviews, participatory action designs that would allow a greater richness in the identification of variables related to these phenomena and, consequently, effective interventions to improve the conditions of these actors.

Despite the fact that exposure to violence is a situation that occurs worldwide, there is no clear trend at the level of intellectual production, neither in terms of the dates of production, nor of the most representative authors on the subject. It seems to be rather a phenomenon explored in a limited way, with many questions but with few answers, and with great challenges for researchers when investigating and accessing the necessary information, since they face this type of variables: (1) the distancing of own actors, (2) the difficulty to reach the zones of conflict, (3) the little access to military personnel and the possibility of talking about the conflict without political interests, and (4) the limited times in the analysis processes to perform field work.

Studying little explored groups could be of great relevance, since new and necessary explanations are provided. In this way, the study of ex-combatants, for example, being the area with the least work according to this review, could help to understand the current processes of reincorporation into the civilian life of ex-combatants who have promoted processes of peace and disarmament movements, as well as understanding why peace processes fail, why some return to arms and why others manage to adjust, questioning from there what could be the cultural practices around the organization as common citizens and their relationship with the emotional processes and social interactions.

The review carried out has some strengths, as it was carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the PRISMA group to ensure that the information, the review process and the analyzes were sufficiently described. In addition, relatively open inclusion criteria were chosen to identify a wide range of studies in the field. This happened because the objective was to provide an overview of the approaches, designs and measurements of the study implemented, as well as the environments. For the development of future intervention studies in the field, it is suggested that search strategies be used with additional criteria, and delimited by different approaches from psychology, and thus recognizing more precisely which topics are mostly addressed by each theoretical orientation and which orientation has more experience on the subject.

Additionally, since the articles most commonly found were those of a quantitative nature, it is pertinent that future research can carry out a meta-analysis and recognize from this the levels of estimation of the effect in the various interventions and measurements that have been carried out. It is suggested that next works begin to investigate other types of actors, such as civil population, ex-combatants, families of the military. Therefore, the perspectives and discourses that have been built around political violence can be expanded.

Finally, some additional limitations must be pointed out, such as the publication bias, a limitation already documented in other systematic reviews, in which there is an alteration of results due to the editorial tendency to publish mostly significant results and the exclusion of unpublished studies that could lead to confusion in the results, as well as eliminating the studies that are published in non-indexed journals or studies carried out in educational institutions, such as master’s and doctoral degree theses, which are possibly a source of additional and updated information for the analysis of this topic.

To conclude, it is important to recognize that the databases contemplate differences in their nature and form of search and that a better investigation could include data from field research at a local level. The research allowed to delimit a psychiatric posture clearly worked in front of the emotional processes and the social interaction and to the few works from other postures of the psychology in which life trajectories, manifestations of suffering and vital social structures in actors different than the veterans of war and active soldiers are recognized, and under investigation models where the position of behavior analysis is developed. It is expected, then, that the combination of these findings opens possibilities of analysis and understanding from studies that accompany not only processes of reconstruction of work, family life, reconciliation and the strengthening of affective ties at the individual level, but, at the same time, an approach of the group context (social and political) in which these individual responses have taken place.

5. Statement of author’s contributions

SR is the first author of this study, responsible for designing and writing its protocol, searching the literature, reading the initial summaries and extracting data from possible eligible studies. He is also responsible for data analysis and document writing. MN is the second author, responsible for refining search strategies, guiding the article eligibility process, supervising data analysis and reviewing the writing process of the document.