1. Introduction

COVID-19 is the name given to the disease caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARSCoV-2) (Gorbalenya et al., 2020). The worldwide outbreak of this novel coronavirus (COVID-19), which started in China, has led to a public health emergency of international concern. In absence of vaccinations and antivirals to fight it, and taking as a reference the measures taken in previous outbreaks of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) (Hsieh et al., 2007), quarantine and isolation are considered the most effective measures for its containment (Zhai et al., 2020).

This new coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) has rapidly propagated across countries, causing severe disease and sustained person-to-person transmission, leading to explosive outbreaks, even in confined settings (G. Li et al., 2020; Mizumoto et al., 2020). Thus, quarantine alone is not enough to prevent the virus from spreading, and it is a reason for strong global concern (Sohrabi et al., 2020). Due to the impossibility of controlling the disease and the severity of the risk, it is not surprising for the population to feel anxious about possible contagion (Zandifar & Badrfam, 2020). Worry is repetitive negative thinking about the uncertainty of future events developing under stress (Skodzik et al., 2016), in which one feels unable to cope with the threat (Soriano et al., 2019). This negative affect usually varies widely, beyond emotions like the nervousness, unease or fear typically associated with it, such as irritability and agitation (emotions quite similar to those in generalized anxiety disorder), despair, annoyance, sadness (which are expected to occur in disorders such as depression), impatience, jealousy, stress, and displeasure (Gould et al., 2018). High levels of perceived threat from COVID-19 particularly influence the appearance of a negative mood state and feelings of irritation, anxiety, despondency or sadness in the general population, which, in turn, promote a cognitive state of worry about the virus (Pérez-Fuentes et al., 2020). This state of overestimation of threat and intolerance to uncertainty, associated with symptoms of hypochondriasis and depression, may partly originate from dysfunctional beliefs about disease acquired early in life, and triggered by a critical incident (Arnáez et al., 2019).

In the evolution of worry, associated negative feelings tend to diminish with age (Arnáez et al., 2019; Pietrzak et al., 2012). However, older people are more nervous when they worry about their health (Wuthrich et al., 2015). Studies such as the one by Ro et al. (2017) have shown that worry about a pandemic affects women, those with higher daily stress, and those who think they have poor health, that is, those who perceive themselves to be more susceptible. Nevertheless, in the case of COVID-19, the epidemiological data show that the individuals at highest risk of mortality are men, more than women, and the elderly (Borges do Nascimiento et al., 2020; Shim et al., 2020).

Nevertheless, such feelings and negative emotions may even appear in those who are not at risk of becoming ill in public health events, such as the current coronavirus outbreak (Montemurro, 2020). Emotions and feelings related to worry about the disease combine with distress generated by the home confinement decreed by the state of emergency in Spain (Real Decreto 463, 2020, march 14). Zhou (2020) suggested that in countries such as China, coupled with the increase in confirmed cases and deaths, negative emotions spread through the population in quarantine, generating considerable feelings of fear, anxiety, sadness, guilt, and nervousness, and threatening the mental health of a large number of people. Quarantine, one of the oldest ways in history of containing infectious diseases, is defined as the restriction or segregation of individuals who may have come into real or potential contact with transmissible pathologies, until the time in which is certain they no longer constitute a health risk (Conti, 2017). The psychological impact of home confinement can generate posttraumatic stress symptoms, confusion, and rage. Individuals who spend most of their time in quarantine perceive an especially strong threat of infection, frustration and boredom, feel lack of supplies and adequate information, and suffer social stigmatization or financial loss (Brooks et al., 2020). Along this line, Li et al. 2020 found in a study of emotional indictors in a group, before and after the COVID-19 emergency was declared, that negative emotions (such as anxiety, depression, and hostility) and sensitivity to risk increased significantly, while positive emotions, such as happiness, decreased.

Age is another of the individual characteristics related to a stronger emotional impact of confinement. For example, in children and adolescents, uncertainty, changes in routine, and emotional changes undergone by the adults they live with can cause restlessness, distress, anxiety, sadness or worry, which are manifested through both direct externalization of these emotions and defiant behavior (Dalton et al., 2019; Ruiz-Hernández et al., 2020). Along the same line, Jiao et al. (2020) showed that isolation due to COVID-19 caused a strong emotional impact on children and adolescents, which turned into irritability, restlessness, and lack of attention, fear and nightmares. However, other authors have shown that older adults may experience more anxiety and depressive symptoms from this epidemic (Lima et al., 2020; Nguyen et al., 2020), because they are usually not as good at managing stressful events (Molero et al., 2018). These results are contrary to those found during previous outbreaks of coronavirus, where psychiatric morbidity was associated with being younger (Sim et al., 2010).

Along with age, sex is also a sociodemographic variable that has been related to the emotional impact of emergencies (Acosta & Herrera, 2018; Pulopulos et al., 2018). Among minors, girls show higher risk of developing posttraumatic stress syndrome (PTSS) after severe situations (Danese et al., 2020, Li et al. 2020. Liu et al. (2020) also showed that after evaluating posttraumatic stress symptoms in the Chinese population in quarantine because of COVID-19, women showed higher PTSS with re-experiencing negative alterations in cognition and mood, as well as hyperexcitation. Wang et al. (2020) found that the psychological impact of the COVID-19 outbreak in that country was significantly lower in men, who, however, scored higher in stress, anxiety, and depression.

Similarly, education has been related to emotional alteration during confinement because of the virus, where those with university degrees are the most affected (Liu et al., 2020; Nguyen et al., 2020). In this respect, studies done in other countries where the epidemic began before Spain showed a 25% prevalence of anxiety-related feelings among university students during confinement from COVID-19 (Cao et al., 2020). However, other studies have found that individuals with no education, compared to those who had some education, underwent the most emotional alteration, such as sadness and depression (Wang et al., 2020). This may be due to a stronger perception of risk from the virus among those with a lower education (Kim & Kim, 2018), especially considering that health education has been shown to exert a protective effect against depression, improving quality of life during confinement for the epidemic (Nguyen et al., 2020). In this line, a recent publication showed that anxiety levels in medical students during the pandemic remained stable, possibly due to knowledge of the transmission, prognosis, and prevention of the disease (Lasheras et al., 2020). Marital status is another of the sociodemographic factors which has shown a significant relationship with developing psychological alterations, such as anxiety and depression, during coronavirus outbreaks, as married couples showed fewer of these symptoms (Sim et al., 2010). Nevertheless, some studies have found that marital status and being a parent are not associated with the emotional state of people in quarantine (Nguyen et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020).

Studies on the psychological impact of previous outbreaks of SARS from coronavirus in the general population have found that around 25% develop psychiatric morbidity such as anxiety, somatic symptoms, social dysfunction, and depression, which in turn is related to later development of posttraumatic stress (Sim et al., 2010). And likewise, a recent meta-analysis showed that the proportion of depression in the general population is seven times higher since the start of the pandemic, and as high as 25% of the world population (Bueno-Notivol et al., 2020). Therefore, and as emphasized by the health consultants of some governments, any approach to the COVID-19 public health emergency must attempt to minimize the negative psychological as well as physical impacts of this virus (Horton, 2020); otherwise, if the immediate and long-term psychological effects of this global situation are ignored, the impact could be immeasurable (Dalton et al., 2019). Therefore, the objective of this study was to analyze the mood and affective balance of Spaniards in quarantine. It further attempted to determine the association of sociodemographic variables and mood with the negative affective balance. The first hypothesis posed was that sociodemographic characteristics such as age and education would be negatively associated with negative affective state and emotions of sadness, anxiety, and hostility (H1). The second hypothesis was that women and single people would have a more negative affective and emotional state than either man or couples, who would have more positive affect and emotions (H2). Finally, it was expected that with regard to the sociodemographic and emotional characteristics of the participants, women who had more negative emotions would have a higher probability of developing negative affect than older individuals with a higher education, who would be more cheerful and less likely to develop them (H3).

2. Method

2.1 Participants

The original size of the sample of the general Spanish population was N = 1043. Based on the answers to control questions (CQ) inserted in the questionnaires, cases in which random or incongruent answers were detected were discarded (-29), leaving a final sample of 1014. At the time of data collection, the participants were under home confinement due to the state of emergency decreed by the government of Spain in response to the current COVID-19 pandemic.

2.2 Instruments

An ad hoc questionnaire was used to collect sociodemographic data. Items included sex, age, marital status, care of minor children, and education.

The emotional situation at the time of evaluation was found using the Spanish Scale for Mood Assessment (Escala de Valoración del Estado de Ánimo (EVEA); Sanz, 2001). This instrument evaluates transitory moods and classifies them in four subscales (anxiety, sadnessdepression, anger-hostility, and happiness), with 16 items rating how much the participant identifies with the different moods enumerated on a scale of 0 (not at all) to 10 (very much). Reliability found was ω = 0.88, GLB=0.89 for anxiety, ω =0.88, GLB=0.90 for sadnessdepression, ω =0.96, GLB=0.97 for anger-hostility, and ω =0.85, GLB=0.88 for happiness.

Table 1

| Sadness-depression | Anxiety | Anger-Hostility | Happiness | Positive affect | Negative affect | ||

| Age | Pearson’s r | -.130*** | -.113 *** | -.044 | -.117*** | -.010 | -.213*** |

| Upper 95% CI | -.069 | -.052 | .017 | -.056 | .052 | -.153 | |

| Lower 95% CI | -.190 | -.173 | -.106 | -.178 | -.072 | -.271 | |

| Education | Pearson’s r | -.062* | -.024 | -.114*** | .022 | -.081** | -.075* |

| Upper 95% CI | -.001 | .037 | -.052 | .084 | -.019 | -.013 | |

| Lower 95% CI | -.123 | -.086 | -.174 | -.039 | -.142 | -.136 |

Emotional state manifested during the past week was evaluated using the Spanish adaptation of the Affective Balance Scale (Godoy-Izquierdo et al., 2008; Warr et al., 1983). This instrument consists of 18 items answered on a Likert-type scale with three answer choices on the frequency the participant experienced the moods described in the past week (1= “hardly ever or never”, 2= “sometimes”, 3= “Often or usually”). The scale measures directly positive and negative experiences. The reliability indices found were ω =0.82, GLB=0.83 and ω =0.79, GLB=0.82, respectively.

2.3 Procedure

Data for this cross-sectional study were collected using a CAWI survey (Computer Aided Web Interviewing), which included, in addition to the validated questionnaires, a series of questions for collecting sociodemographic data. The survey was spread through the social networks (snowball sampling), and remained available for one week (specifically, the first week of confinement of the Spanish population from March 18-23, 2020). Participation was voluntary, and on the first page before answering the questionnaire, participants were provided with information on the study and its purpose, where they also had to check a box indicating they are aware of the informed consent before starting to complete the survey. Participants were also asked to answer sincerely and guaranteed the anonymity of their answers. Control questions were included throughout the questionnaire for detection of random answers. This study was approved by the University of Almeria Bioethics Committee.

2.4 Data analyses

First, frequency and descriptive analyses of sociodemographic data were performed. The association of variables was explored with the Pearson bivariate coefficient. Any differences between the groups were examined using the Student’s t-test for independent samples or ANOVA, depending on the case. The Cohens d (1988) was used as a measure of the effect size following the criteria: d < 0.50 small effect size, d from 0.50 to 0.80 medium, and d 0.80 large.

Then a binary logistic regression model was estimated using the enter method. The dependent variable for this was the Affective Balance Index, previously dichotomized and recoded as a dummy variable (0=Positive affective balance, 1=Negative affective balance). The sociodemographic variables and moods were included as predictors.

The McDonalds omega coefficient (McDonald, 1999) was estimated following the guidelines of Ventura-León and Caycho (2017) to examine the reliability of the instruments used to collect the data. The Greatest Lower Bound (GLB) was also estimated. The SPSS v. 23.0 statistical package was used for data processing and analysis.

3. Results

3.1 Sociodemographic Characteristics of the participants

The mean sample age was 40.87 (SD = 12.42) in a range of 18-76. Of these, 67.2% (n = 681) were women and 32.8% (n = 333) were men, with a mean age of 39.88 (SD = 12.35) and 42.92 (SD = 12.33), respectively.

Marital status distribution in the sample was 60.1% (n = 609) married or stable partner, 30.9% (n = 313) single, 8.1% (n = 82) divorced or separated, and 1% (n = 10) widowed. Of these, 35.9% (n = 364) had minor children in their care. Finally, with respect to education, 78.7% (n = 798) had a higher education, followed by 16% (n = 162) high school, 5% (n = 51) primary, and 0.3% (n = 3) with no education.

3.2 Mood and affective balance under home confinement

Table 1 shows the correlation matrix of each of the moods by participant age and education. Age correlated negatively with Sadness-Depression (r = .13, p <.001), Anxiety (r = .11, p < .001), and Happiness (r .11, p < .001). Level of education was negatively correlated with Sadness-Depression (r = .06, p < .05) and Anger-Hostility (r = .11, p < .001). In addition, there is a negative correlation between age and negative affect (r = .21, p < .001). Level of education was negatively correlated with both positive (r = .08, p < .01) and negative (r = .07, p < .05) affect.

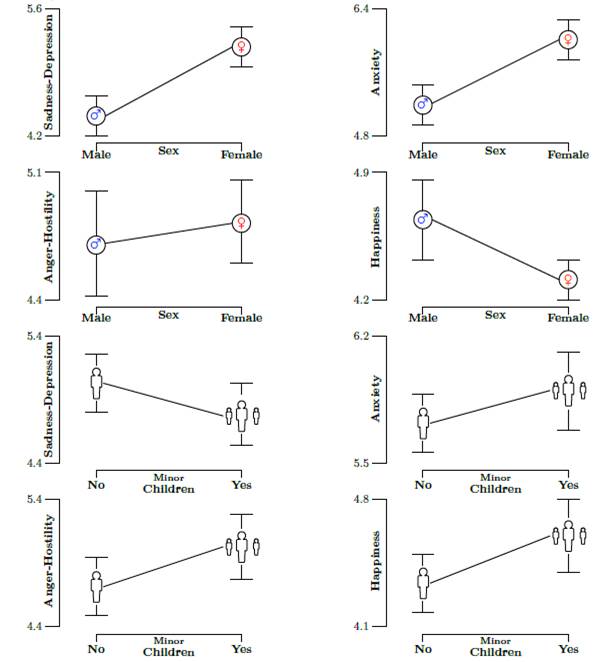

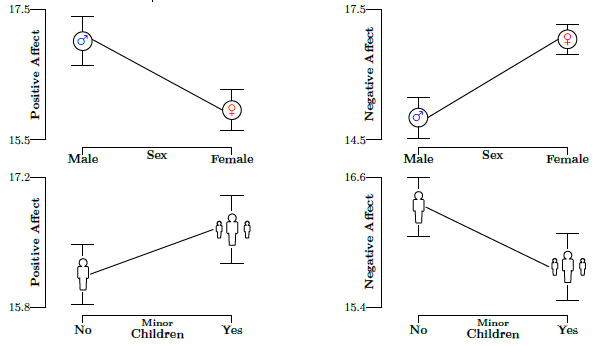

A comparison of means was done for each mood by sex and by whether there were minor children in their care. Table 2 and Figure 1 show the statistically significant differences between sex in Sadness-Depression (t = 5.47, p < .001, d = .36) and Anxiety (t = 6.42, p < .001, d = .43), in which women had the highest scores in both cases. However, men scored significantly higher in Happiness (t = 2.38, p < .05, d = .15) than women. In addition, Table 2 shows the significant differences in two opposite moods: Sadness-Depression (t = 2.13, p < .05, d = .14), with a higher score in the group without children, and Happiness (t = 2.42, p < .05, d = .15), with higher scores for those with children in their care. In all cases, the effect size revealed by the Cohens d was small.

Finally, no statistically significant differences by marital status were found in any of the moods analyzed: Sadness-Depression (F = .98, p = .40), Anxiety (F = .08, p = .97), Anger-Hostility (F = .26, p = .85) or Happiness (F = .96, p = .41).

As shown in Table 2 and Figure 2, men scored significantly higher in positive affect (t = 3.98, p < .001, d = .26) than women, and women scored higher in negative affect (t = 7.40, p < .001, d = .49) than men. By care of minor children or not, differences were observed in positive affect (t = 2.03, p < .05, d = .13), where those with minor children in their care had the highest mean scores.

Table 2 Mood and Affective balance. Descriptive and Students t, by sex and minor children

| Mood | Male | Female | t | Mean Dif | SE Dif | 95% IC | Cohen’s d | |||||

| N | M | SD | N | M | SD | Lower | Upper | |||||

| Sadness-Depression | 333 | 4.44 | 2.02 | 681 | 5.25 | 2.29 | -5.47*** | -.81 | .14 | -1.10 | -.51 | -.36 |

| Anxiety | 333 | 5.16 | 2.11 | 681 | 6.10 | 2.22 | -6.42*** | -.93 | .14 | -1.22 | -.65 | -.43 |

| Anger-Hostility | 333 | 4.71 | 2.54 | 681 | 4.85 | 2.66 | -.80 | -.14 | .17 | -.48 | .20 | -.05 |

| Happiness | 333 | 4.61 | 1.84 | 681 | 4.33 | 1.75 | 2.38* | .28 | .11 | .05 | .51 | .15 |

| Mood | No minor children | Minor children | t | Mean Dif | SE Dif | 95% IC | Cohen’s d | |||||

| N | M | SD | N | M | SD | Lower | Upper | |||||

| Sadness-Depression | 650 | 5.10 | 2.27 | 364 | 4.78 | 2.16 | 2.13* | .31 | .14 | .02 | .60 | .14 |

| Anxiety | 650 | 5.72 | 2.27 | 364 | 5.92 | 2.14 | -1.31 | -.19 | .14 | -.47 | .09 | -.08 |

| Anger-Hostility | 650 | 4.69 | 2.67 | 364 | 5.02 | 2.53 | -1.93 | -.33 | .17 | -.66 | .00 | -.12 |

| Happiness | 650 | 4.32 | 1.81 | 364 | 4.60 | 1.74 | -2.42* | -.28 | 0.11 | -.51 | -.05 | -.15 |

| Affective balance | Male | Female | t | Mean Dif | SE Dif | 95% IC | Cohen’s d | |||||

| N | M | SD | N | M | SD | Lower | Upper | |||||

| Positive Affect | 333 | 16.97 | 4.05 | 681 | 15.99 | 3.49 | 3.98*** | .98 | .24 | .05 | .51 | .26 |

| Negative Affect | 333 | 14.96 | 3.51 | 681 | 16.75 | 3.66 | -7.40*** | -1.78 | .24 | -2.26 | -1.31 | -.49 |

| Affective balance | No minor children | Minor children | t | Mean Dif | SE Dif | 95% IC | Cohen’s d | |||||

| N | M | SD | N | M | SD | Lower | Upper | |||||

| Positive Affect | 650 | 16.13 | 3.66 | 364 | 16.63 | 3.78 | -2.03* | -.49 | .24 | -.97 | -.01 | -.13 |

| Negative Affect | 650 | 16.31 | 3.69 | 364 | 15.90 | 3.73 | 1.66 | .40 | .24 | -.07 | .88 | .10 |

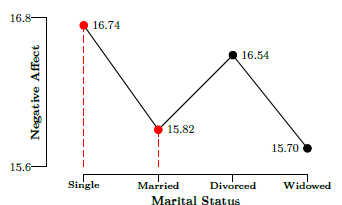

Finally, in the comparison of mean scores on positive and negative affect by marital status, no differences were found for positive affect (F = 1.63, p = .18). However, there were statistically significant differences for negative affect (F = 4.60, p < .01, η 2 = .01) between the single (M = 16.74, SD = 3.72) and married (M = 15.82, SD = .58) groups. The following figure (Figure 3) shows mean scores on negative affect for each marital status group.

3.3 Binary logistic regression model for predicting the negative affective balance

The sociodemographic variables and moods were taken as the predictors for estimating the logistic regression model. Polytomous variables were dichotomized by creating a dummy variable of 0 or 1. Thus, marital status was recoded as 0= partner and 1= no partner (this category includes single, divorced and widowed). The dependent variable was the affective balance index in a range of -18 to 18 points It was considered a negative affective balance if scores were below 0 and positive if they were above it, and this variable was then recoded as: 0= Positive affective balance and 1= Negative affective balance.

The results of the logistic regression analysis are presented in Table 3. The multivariate association measures found show that the likelihood of having a negative affective balance during the week of home confinement was 1.62 times higher for women than for men, 1.53 times higher with a Sadness-Depression mood, and 1.46 times higher with an Anxiety mood. On the contrary, older age and Happiness were protective variables against a negative affective balance.

The overall fit of the model (χ 2 = 540.80; df = 9; p < .001) was confirmed by the Hosmer-Lemeshow test (χ 2 = 5.94; df = 8; p = .654). The Nagelkerke R 2 indicated that 58% of the variability in the response variable could be explained by the logistic regression model. Based on case classification, probability of the logistic function being correct was also estimated at 80.8% with a false positive rate of .18 and false negative of .79.

4. Discussion

Confinement due to the COVID-19 pandemic may have repercussions on the psychological wellbeing of the general population, especially in those most vulnerable (Dalton et al., 2019; Shim et al., 2020). The objective of this study was therefore to find out the influence of certain sociodemographic variables on the emotional and affective balance. Based on the results, and according to our first hypothesis, we can state that age was associated with negative affect, sadness-depression, anxiety, and happiness. Specifically, older age was associated with a decrease in negative feelings of sadnessdepression, and anxiety, as well as negative affective state and increased happiness. This result is in agreement with those found during previous outbreaks of coronavirus, in which the younger population showed more negative emotions (Sim et al., 2010). It was also shown that a higher education is related with fewer negative feelings of sadness and anger-hostility, as in other studies done during the epidemic in other countries (Liu et al., 2020; Nguyen et al., 2020). Concerning the affective situation, a higher education was associated with both low positive and negative affective states. Thus, it seems that higher education enables adequate comprehension of information on COVID-19, and it would help reduce emotional alterations that arise when perceived risk is high, without this impeding understanding the real implications of the virus, and therefore, altering the positive affective state (Kim & Kim, 2018; Lasheras et al., 2020).

Turning attention to our second hypothesis, no significant differences in emotions were found by marital status; however, negative affect was higher among married couples than singles, while caring minor children was related to higher levels of happiness, and not having care of children with higher scores in sadness-depression. This differs from the results of studies done in a Chinese population, where no relationship was found between these family variables and the emotional state of those in quarantine (Nguyen et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020).

Furthermore, in the relationship of sex to emotional state, men were found to show more happiness and a positive affective state, while women showed a higher score in negative affective state and more feelings of sadnessdepression and anxiety, in line with other studies (Wang et al., 2020). Although this study evaluated emotional states at the time of assessment and affective balance in the past week of confinement, these results support the relationship shown in other studies between women and emotional alterations after quarantine, such as the appearance of posttraumatic stress symptoms (Liu et al., 2020).

Finally, to test the third hypothesis, the sociodemographic variables were analyzed to find out whether they were associated with a higher probability of developing a negative affective state during quarantine. In fact, being a woman and scoring high on negative feelings, in particular sadness-depression and anxiety, were associated with a greater possibility of showing a negative affective balance, while older age and happiness were variables related to lower risk. This model, which explained much of the variability in the negative affective balance in the sample, was in harmony with previous literature. A study by Liu et al. (2020) showed that being a woman was a risk variable for developing negative emotional states. Thus, women perceived more concern for the disease, which had a stronger impact on their affective level during the pandemic (Ro et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2020), while emotional symptoms, such as anxiety or depression, are related to later development of affective alteration (Sim et al., 2010). The result, showing age as a variable associated with lower risk, should be taken with precaution. The mean age of the sample was not very high, and very few individuals were within the age group where there is high risk of mortality from COVID-19 (Borges do Nascimiento et al., 2020; Shim et al., 2020); therefore, negative emotional states linked to higher perceived risk may not have been present (Gould et al., 2018; Zandifar & Badrfam, 2020). Thus, young age has been linked to higher psychiatric morbidity in outbreaks of epidemics (Sim et al., 2010).

Table 3 Results derived from the logistic regression for the probability of a negative affective balance

| Variables | β | p-value | OR | 95% CI |

| Age | -.016 | .045 | .984 | .969, 1.000 |

| Sex (a) | .484 | .013 | 1.622 | 1.109, 2.374 |

| Marital status (b) | .236 | .252 | 1.266 | .846, 1.895 |

| Minor children (c) | -.240 | .247 | .787 | .524, 1.181 |

| Education | .065 | .702 | 1.067 | .765, 1.489 |

| Sadness-Depression | .429 | .000 | 1.536 | 1.366, 1.727 |

| Anxiety | .381 | .000 | 1.464 | 1.294, 1.657 |

| Anger-Hostility | .006 | .899 | 1.006 | .922, 1.097 |

| Happiness | -.659 | .000 | .517 | .455, .588 |

| Constant | -1.460 | .068 | .232 |

4.1 Limitations of this study

Some limitations should be pointed out. In the first place, the presence of COVID-19 symptoms or diagnosis was not considered, in either the participant or in close friends and family, or perceived health condition, which could affect the emotional and affective impact during confinement of the general population, and this detracts from the possibility of comparing our results. Moreover, as it has already briefly been mentioned above, the mean age of the sample was around 40; therefore, we cannot be sure whether age was a constant protective variable or only linked to adulthood. Furthermore, the study design was cross-sectional, and data were collected during the first week of confinement; consequently, no conclusions related to the evolution of the variables analyzed are possible. A longitudinal study would enable progress in the analysis of the variables included in this study. Similarly, future studies should include other variables, such as participants place of residence or economic and employment status, which could have an essential role in the cognitive and emotional result of the pandemic. Perceived threat and economic situation have been demonstrated to influence emotions felt toward COVID-19 (Brooks et al., 2020), and the resident population in the areas of healthcare most affected by the virus or where the economic situation is under duress due to the pandemic could experience more negative emotions.

5. Conclusions

The coronavirus is generating a scenario of uncertainty in which primary importance is now given to impeding increase in the rate of infection and the death toll. However, as shown by studies done in populations where the outbreak began before it arrived in Spain, expansion of negative emotions during confinement is almost as rapid as the virus itself. The psychological impact of confinement may be severe; therefore, it is indispensable to give public attention to psychological problems derived from confinement, and measures should be prepared to prevent future emotional disorders, such as severe stress and posttraumatic stress syndrome. To date, there are few studies analyzing the role of sociodemographic variables in the emotional and affective impact on the general population during states of confinement, and those that have analyzed them for COVID-19 are even fewer. In the light of the findings of this study, it seems that special attention should focus on young women experiencing emotions such as sadness or anxiety during confinement, and single people, those without children or with a low level of education, as these characteristics were related to a higher probability of showing a negative affective state. On the contrary, maturity and feelings of happiness are linked to a lower pres ence of negative affect. Thus, knowing the groups with greater likelihood of developing emotional and affective alterations can facilitate the detection and prevention of later disorders, which could become an important public health problem after the COVID-19 pandemic.

7. Contributors Statement

M.d.C.P.F., M.d.M.M.J., M.d.M.S.M. and A.M.M. contributed to the conception and design of the review. J.J.G.L. applied the search strategy. All authors applied the selection criteria. All authors completed the assessment of bias risk. All authors analyzed and interpreted the data. M.d.M.M.J., M.d.C.P.F., and A.M.M. wrote this manuscript. M.d.C.P.F. and J.J.G.L. edited this manuscript. M.d.M.M.J. is responsible for the overall project.