1. Introduction

Parent-child relationships have a significant impact on children’s socioemotional (Collins & Steinberg, 2006), moral, behavioral (Mounts & Allen, 2019), and mental development. Scientific research has identified associations of parents’ psychological control with problems in children’s emotional, cognitive, and behavioral development (Zarra-Nezhad et al., 2015).

Initially, Baumrind (1991) suggested the existence of three parenting styles: authoritarian, authoritative, and indulgent. Later, Maccoby and Martin (1983) expanded this proposal to a bidimensional-structure model (demandingness and responsiveness), resulting in four types of parents: authoritative, authoritarian, indulgent, and neglectful.

The exploration of the relationship between parenting styles and children’s socioemotional development revealed that authoritative parents show a rational attitude during rearing, have clear and demanding limits and rules, are emotionally warm, pay attention, favor reciprocal exchanges, offer good behavioral models, keep high expectations, and tend to monitor their children’s behavior without being restrictive or imposing (Farrell, 2015). This parenting style is associated with children with better socioemotional development, greater selfconfidence, self-esteem, and self-image, as well as better coping skills (Rodrigues et al., 2013).

For their part, authoritarian parents are strict and imposing, make disproportionate rules, exercise power without allowing questioning, tend to be emotionally cold, use force to correct behavior, are excessively demanding, are oriented to asserting power for the sake of power and not for the sake of arguments or logic, are intrusive and restrictive, and aim to subdue their children. From this perspective, Lerner and Grolnick (2019) found that this parenting style is associated with children with more aggressive and less supportive behaviors in their relationships with peers and contemporaries.

As regards indulgent parents, they are permissive, set few boundaries, do not lead their children to obey the rules, do not exert control or external monitoring, do not favor their children’s self-regulation, are lenient, have no problem with their children making their own decisions without consulting them, are usually loving, and like talking with their children, but do not guide their behavior (García-Peña et al., 2018).

Finally, neglectful parents lack commitment to their parenting responsibilities, do not show interest in drawing boundaries, lack emotional warmth, are careless and lenient concerning their rearing style, and, in some cases, show no liking for their role as parents and can even reject their children (Luján Aguirre, 2019). Children raised under this parenting style tend to be rebellious, are prone to show antisocial behaviors, assume few civic responsibilities, and find social interactions difficult (Ekechukwu, 2018).

Multiple studies have proven the benefits of the authoritative parenting style (demandingness paired with responsiveness) and have defined it as the most proper technique for children’s optimal development and their future as adults at the emotional, social, and cognitive levels (Stafford et al., 2016). Adolescents from authoritative families develop increased self-esteem and are less prone to consuming psychoactive drugs (Hoffmann & Bahr, 2014). In addition, authoritative styles are linked to better academic results (Spera, 2005) and greater self-efficacy and self-improvement skills (Pinquart & Kauser, 2018).

In short, studies reveal a repeated pattern of balance/imbalance of emotional, cognitive, socio-affective, and behavioral skills with regards to the parenting styles experiencedbychildren during childhood andadolescence. Given that most parenting styles scales found in the literature were designed and validated in European countries or in the United States (Rajan et al., 2020), and that only some of them were implemented in Latin America, there are few instruments validated to measure this construct in Peru. Particularly, there are reports on an exploratory and confirmatory analysis of the Family Parenting Styles (ECF-29) scale with a sample of 609 high school students from public educational institutions (Estrada-Alomía et al., 2017), as well as a study on the Measure of Parental Style (MOPS) scale with 2370 adolescents aged 13 to 19 (Matalinares et al., 2014).

Recently, a research work to validate the Maternal Behavior Q-Sort (MBQS) scale, containing three factors and 90 questions, was also reported in Peru (Bárrig-Jó et al., 2020). Finally, another paper addressed the validation of the Parental Behavior Scale (PBS), consisting of eight factors and 45 questions (Manrique-Millones et al., 2014), which was applied to a sample of 591 parents of children in sixth grade of primary education in this country.

As for the scale of interest to us, there is a Peruvian confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of the Lawrence Steinberg’s Parenting Styles Scales, applied to 224 adolescents between 11 and 19 years old (Merino-Soto & Arndt, 2004). The study found that both the overall scale and the three subscales have construct validity and internal reliability; however, the scale version used in Peru consisted of 22 questions.

We consider that the scale developed by Steinberg (Lamborn et al., 1991) is the most appropriate to be validated in Peruvian population, considering its crosscultural use and the fact that results are obtained through direct self-reporting by the adolescents, which favors a quick administration and the identification of five types of parents. Thus, the objective of this research was to assess the psychometric properties of the Steinberg’s parenting styles scale in Peruvian children and adolescents.

2. Methodology

2.1. Design

This was a quantitative, cross-sectional, psychometric research study based on Steinberg’s theoretical proposal (Lamborn et al., 1991), which used a CFA.

2.2. Sample

The study focused on students in sixth grade of primary school to third grade of secondary school of basic education, enrolled at and regularly attending public educational institutions located in marginal urban areas of Lima, Peru. The study excluded students who did not attend school on the day of data collection.

The minimum sample size calculated was 260, as we assumed the classical criterion of 10 subjects per each variable of the model (Kline, 2015). However, we included 563 students aged between 10 and 17 (mean = 12.96 and standard deviation = 1.31), chosen through nonprobability convenience sampling. As for sex, 54.0% (304) identified as young men and 46.0% (259) as young women. Regarding school grades, 28.2% (159) was in sixth grade of primary school; 29.3% (165), in first grade of secondary school; 24.3% (137), in second grade of secondary school; and 18.1% (102), in third grade of secondary school. The number of average siblings ranged between two to three in each family.

2.3. Instrument

We used the Steinberg’s Parenting Styles Scale (Lamborn et al., 1991) to examine the patterns of competence and adjustment in adolescents and their relationships with parenting styles. The original instrument comprises 26 items grouped in three clusters that define the main parenting aspects: involvement (9 items), psychological autonomy (9 items), and parental supervision (8 items). The first two clusters ask Likert-type questions with answers that range from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). The involvement subscale measures the degree in which the adolescent perceives behaviors of emotional approach, sensitivity, and interest from their parents. The psychological autonomy subscale examines the degree in which parents use democratic, noncoercive strategies and encourage individuality and autonomy. Lastly, the parental supervision subscale consists of two types of questions: two questions with seven answer options and the other six questions (of the type: “How much do your parents TRY to find out where you go at night?”) with three answer options that range from 1 (they do not try) to 3 (they try a lot); this subscale assesses the degree in which parents are perceived as controllers or supervisors of the adolescent’s behavior.

2.4. Procedure

We requested authorization from principals at various public educational institutions located in marginal urban areas of Lima, Peru, to apply the instrument under analysis to schoolchildren between 10 and 17 years old. The school authorities approved the questionnaire. Subsequently, we run a 30-student pilot to determine the understanding of the items and the answer alternatives. During the test, the students reported that they did not understand Item 4: “My parents say that I should stop arguing and give in, instead of making people upset”. Moreover, some students did not answer Item 21: “How much do my parents try to find out where I go at night?” and Item 24: “How much do my parents really know where I go at night?” because they -especially children aged 10 to 11reported that they did not leave their homes at night.

We collected data in 2019. One day before data collection, we requested the informed consent from the parents; likewise, before data collection, we requested the informed assent from the students.

The procedure was standardized for the purposes and objectives of the research. The scale was applied at the classroom, at hours agreed with principals and teachers, by two research team members previously prepared for said application. The team members explained the reason for the research to the participating students, provided some examples of how to answer the test, distributed the material, and were available to them to clear up any doubts.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

For the development of the descriptive and psychometric analyses, we used the RStudio program, version 4.0.3 (2020-10-10), as well as the Psych and Lavaan packages. For the descriptive analysis of the items, we calculated the distribution of frequencies in order to observe the response tendency, mean, deviation, skewness, kurtosis, and corrected discrimination and correlation coefficients between item score and total score obtained in each factor.

As validity evidence, we analyzed the internal structure using a CFA and specifying Steinberg’s theoretical model (Lamborn et al., 1991), which proposes three factors to measure parenting styles. We tested a correlation model and used the weighted least squares means and variance adjusted (WLSMV) estimation method, taking into account the type of scale and the non-normal distribution of data. Then, we determined the overall goodness of fit of the model through Satorra-Bentler’s adjusted χ 2 (p < .05) -a test sensitive to the sample sizeby calculating the ratio between its value and the degrees of freedom. We used other indexes such as the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) to estimate the overall error existing in the model, the comparative fit index (CFI), and the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI). The RMSEA index quantified the divergence between data.

3. Results

Table 1 shows that, in the involvement factor, answer means were around 3; deviations, below 1; and skewness values, negative. This indicates that answers tended to locate in high scales of measurement. The kurtosis, in most items, was below 1, except in Items 1 and 3. The item-test correlations show values above .3.

Concerning the psychological autonomy factor, answer means were around 2. The deviation value was 1 or higher, which indicates adequate variability in responses. In some items, skewness was negative, which means a tendency towards high scales of measurement, and, in other items, it was positive, which suggests a tendency towards low scales of measurement. The kurtosis was below 1 in most items, except for Items 4, 10, and 14. For the item-test correlation, the analysis identified low correlation of Items 2 and 4 with the factor.

Finally, the parental supervision factor showed that answer means were around 2, except for Item 20, whose mean was above 3. The deviation was low, except for Items 19 and 20, which had better response variation. The skewness was negative (i.e., tending to high values of the scale), except for Items 19 and 20, which indicated an inverse behavior. In most items, the kurtosis indicated values below 1, except for Item 23. The itemtest correlation was above .25.

3.1. Relationship Model

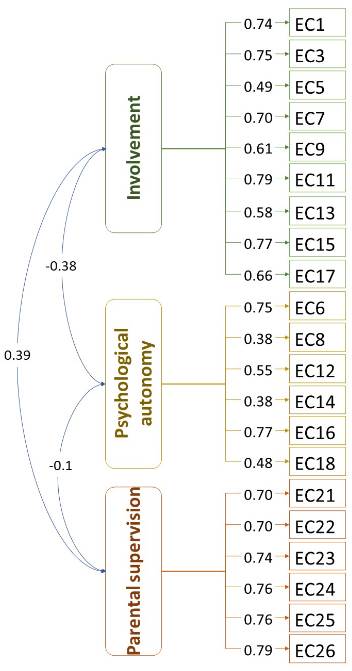

Regarding the CFA, a relationship model was proposed consisting of the three dimensions described byStein-berg et al. (1992): involvement, psychological autonomy, and parental supervision. The results of this models howed good fit:χ2= 469.051(p<.001);df= 184;χ2/df= 2.54; CFI = .95; TLI = .94; RMSEA = .053;SRMR = .063. It is important to note thatχ2/df values lower than 3 indicated adequate model fit(Kline,2015);RMSEA values < .06 suggested good fit; values up to.08, with 90% CI showed acceptable fit. For CFI and TLI, with values≥.90, the model fit was acceptable. The correlation matrix was polychoric, considering the categorical (ordinal) nature of the items. Likewise, the McDonald’s omega index showed over-all consistency of .944 and consistency by factor of ́ω=.889, ́ω=.73, and ́ω=.88, respectively, which demon-strated precision in the measurements for each factor and the overall test. It is worth mentioning that, from the psychological autonomy dimension, Items 2, 4, and 10 were removed for having low factor loadings; meanwhile, from the parental supervision dimension, Items 19 and 20 were deleted for showing high residual (see Figure1). Similarly, there was a covariation between the errors of Items14 and 18 and the errors of Items 15 and 17.

Regarding the covariances between factors, there was a correlation of .38 between involvement and psychological autonomy; a correlation of .39 between parental supervision and involvement; and a correlation of .1 between psychological autonomy and parental supervision (Figure 1).

4. Discussion

Most of the scales that assess parenting styles were designed and validated in European countries or in the United States (Rajan et al., 2020) and only a few were validated in Latin America. In this respect, the Maternal and Paternal Parenting Styles Scale (PSS-MP), consisting of six factors, was validated in Chilean population (Gálvez et al., 2021). Likewise, in Peru, a study reported the convergent validity of the Maternal Behavior Q-Sort (MBQS), which comprises three factors and 90 questions (Bárrig-Jó et al., 2020). Another of the scales validated in the Peruvian population is the Parental Behavior Scale (PBS), composed of eight factors and 45questions. These two last scales require to be applied through observation of maternal or paternal behavior. In this sense, the scale validated in the present study becomes relevant because the measurement can be performed by means of the adolescents’ report and does not require the researcher to visit their homes, which is restricted in times of COVID-19. In addition, the scale has 21 questions that can be quickly answered and allow the identification of five types of parents.

Table 1 Descriptive statistics and analysis of the items of the parenting styles scale

| Factor | Item | M | D | S | K | D |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Involvement | EC1. I can count on my parents’ help if I have any kindof problem | 3.53 | .81 | −1.78 | 2.44 | .54 |

| EC3. My parents encourage me to do my best in thethings I do | 3.54 | .78 | −1.87 | 3.03 | .60 | |

| EC5. My parents encourage me to think for myself | 3.18 | .96 | −.96 | −.13 | .36 | |

| EC7. My parents help me with my assignments if thereis something I do not understand | 2.93 | 1.09 | −.58 | −1.00 | .56 | |

| EC9. When my parents want me to do something, theyexplain why | 3.09 | .95 | −.86 | −.16 | .52 | |

| EC11. When I get a low grade in school, my parentsencourage me to try harder | 3.35 | .93 | −1.35 | .75 | .62 | |

| EC13. My parents know my friends | 3.26 | .92 | −1.09 | .23 | .43 | |

| EC15. My parents take time to talk with me | 3.12 | 1.00 | −.84 | −.46 | .64 | |

| EC17. In my family, we do things to have fun or have agood time together | 3.30 | .97 | −1.19 | .23 | .54 | |

| Psychological autonomy | EC2. My parents say or think that I should not arguewith adults | 2.89 | 1.06 | .56 | −.92 | .15 |

| EC4. My parents say that I should stop arguing and givein, instead of making people upset | 2.74 | 1.04 | −.35 | −1.05 | .19 | |

| EC6. When I get a low grade in school, my parents makemy life “difficult” | 1.94 | 1.00 | .70 | −.69 | .39 | |

| EC8. My parents say that their ideas are right and thatI should not contradict them | 2.19 | 1.03 | .46 | −.92 | .33 | |

| EC10. Whenever I argue with my parents, they say thingslike: “You will understand better when you are older” | 2.76 | 1.06 | −.36 | −1.09 | .32 | |

| EC12. My parents do not let me make my own plans anddecisions for things I want to do | 2.15 | 1.01 | .45 | −.90 | .40 | |

| EC14. My parents act in a cold and unfriendly way if Ido something they do not like | 2.35 | 1.01 | .10 | −1.11 | .42 | |

| EC16. When I get a low grade in school, my parentsmake me feel guilty | 1.81 | .95 | .94 | −.15 | .34 | |

| EC18. My parents do not let me do something or be withthem when I do something they do not like | 2.04 | .99 | .55 | −.80 | .40 | |

| Parental supervision | EC19. In a normal week, how late can I stay out of thehouse Monday through Thursday? | 2.59 | 1.66 | 1.09 | .26 | .26 |

| EC20. In a normal week, how late can I stay out of thehouse on a Friday or Saturday night? | 3.15 | 1.88 | .54 | −.91 | .30 | |

| EC21. How much do my parents try to find out where Igo at night? | 2.48 | .71 | −.99 | −.38 | .33 | |

| EC22. How much do my parents try to find out what Ido with my free time? | 2.18 | .68 | −.24 | −.87 | .30 | |

| EC23. How much do my parents try to find out where Iam, mostly in the evenings after school? | 2.34 | .77 | −.67 | −1.02 | .32 | |

| EC24. How much do my parents really know where I goat night? | 2.50 | .69 | −1.04 | −.19 | .29 | |

| EC25. How much do my parents really know what I dowith my free time? | 2.29 | .67 | −.40 | −.78 | .25 | |

| EC26. How much do my parents really know where I am,mostly in the evenings after school? | 2.41 | .74 | −.81 | −.73 | .33 |

Note. M = mean; D = deviation; S = skewness; K = kurtosis; D = discrimination.

In Peru, a previous study validated Steinberg’s Parenting Styles Scale (Lamborn et al., 1991). It explains that the internal structure of the questionnaire applied to Peruvian adolescents was similar to the original questionnaire and that the reliability coefficients were acceptable to moderately low, both for the overall scale and for the three subscales (Merino-Soto & Arndt, 2004). It should be noted that the study used the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, which has severe limitations given that it is not only susceptible to the number of items, but it is less robust than McDonald’s omega coefficient (used in the present study) to the violation of measurement assumptions of instruments such as congeneric scale, nonnormal distribution, correlation errors, and multidimensional scale (Dunn et al., 2014).

According to the results obtained in the present research, the internal structure of the questionnaire is similar to the original questionnaire and has adequate reliability and construct validity. In order to achieve the initial objectives, we decided to implement a model of correlated factors, which comprised the three dimensions proposed by Steinberg’s team (Lamborn et al., 1991): involvement, psychological autonomy, and parental supervision. The results of this model showed good fit, as well as good consistency in the McDonald’s omega index. As regards the covariances, the correlations between involvement and the other two dimensions (psychological autonomy and parental supervision) are noteworthy. From a conceptual point of view, parental involvement seems to be an essential factor of the parenting styles (more significant that the other two) and has great influence on the way parents fulfill the other parental functions (supervision and autonomy-granting) during their children’s growth and in the development of a healthy personality and an adequate behavioral adjustment.

Involvement, defined as the degree to which parents demonstrate interest in their children and provide them with emotional and affective support, is a foundational element of human personality. It is probably due to the impact that responsiveness has on early emotional interactions, such as those observed in the establishment of attachment relationships between emotionally significant figures and children. There is evidence in the scientific literature of the connection between the way in which parents fulfill their parenting practices and the type of early attachment relationship developed (Paolicchi et al., 2017). However, further research is necessary to better elucidate the influence of these affective interaction schemes on parenting styles and their effects on children’s psychosocial development and behavior. The question that remains to be discussed has to do with the items deleted to improve the fit of the model, considering the population under study.

To address this last discussion, it is important to explain that the sample consisted of schoolchildren from marginal urban areas. They had difficulties in understanding Item 2 and some of them asked the examiners about the meaning of the question. These comprehension problems may also have occurred in other items with low factor loadings.

In addition, several studies suggest that the consequences of the parenting styles vary according to the social and cultural contexts of families (Giles-Sims & Lockhart, 2005). For example, factors associated with the authoritative style have more influence on school success in White American adolescents than in the African American group (Steinberg et al., 1992). Similarly, Baumrind’s (1972) initial studies from several decades ago state that the authoritarian style is associated with shyness in European American boys; while, in African American girls, it is more related to assertiveness. This demonstrates that the culture of origin and the social context of children and adolescents modify the consequences of the parenting styles. Cross-cultural comparative results have not shown consistency across the different cultures, ethnic groups, and socioeconomic strata (Spera, 2005).

Darling and Steinberg (1993) have attempted to explain these cross-cultural differences by resorting to the distinction between parenting styles and parenting practices or methods. The former conceptually represent general attitudes and goals in relation to parenting, while the latter refer to the specific techniques used to achieve these goals. Thus, according to these authors, a great variability of specific strategies can be found across cultures.

Some researchers report that the characteristics of the parenting styles vary across cultures (Giles-Sims & Lockhart, 2005) and even across subcultures within the same culture (Molnar et al., 2003). This phenomenon may be due, in part, to prevailing beliefs about the effectiveness of certain educational strategies on behavior in each context or to existing expectations of the parents (Gaxiola-Romero et al., 2006).

Consequently, the conceptualization of the parenting styles in the Peruvian culture may differ marginally from those found in other cultures and countries; especially in North America, where most of the studies using the Steinberg’s scale have taken place (Lamborn et al., 1991).

4.1. Limitations

This study had some limitations. First, given that the sample consisted of schoolchildren from basic-education institutions located in urban marginal areas, the scale should be validated in other population segments. Second, the information was obtained through self-report scales and participants had difficulties in understanding some items; however, the data collection process was carried out by a trained team that ensured that the procedures were always followed in a standard manner in all educational institutions. Finally, parenting, as perceived and understood by children, is different from that perceived and understood by preadolescents and adolescents.

4.2. Future Considerations

The results of the study will be useful to understand the parenting styles and their effects on the emotional, cognitive, psychosocial, and behavioral development of children, adolescents, and adults, through the use of this scale validated for Peru. It will also be useful for comparative investigations in different contexts, especially in Latin American countries.

5. Conclusions

The results of the assessed model of correlated factors indicate adequate psychometric properties of the parenting styles scale proposed by Steinberg et al. (1992) and its three dimensions (involvement, psychological autonomy, and parental supervision) in a population of Peruvian children and adolescents. The overall scale shows an internal structure similar to the original questionnaire and has adequate construct validity and reliability, determined through the McDonald’s omega index (ω´ = .944). The model demonstrates good fit.

The proposed factor model (Steinberg’s three dimensions of parenting styles) has been validated by the findings of the present study, as well as the construct as a whole (parenting styles). The strengths of the instrument have also been highlighted, making it a potentially useful scale for studying parenting styles and their implications for mental health, cognitive and emotional development, and behavior of young people among the ages studied.

Notwithstanding the above, it is key to point out that, in order to improve the fit of the model, three items of the psychological autonomy dimension and two items of the parental supervision dimension had to be deleted because of their low factor loading (less than .2) and high residual (see Figure 1).

The results obtained in this study constitute a significant contribution for further empirical research, given that there are few instruments validated in Peru to measure parenting styles from children’s and adolescents’ perception. This will favor and encourage further studies on this topic, using an instrument with proven psychometric properties. Finally, it is crucial to report on the need to carry out additional studies with samples of greater age range and various subcultures from the highlands and jungle of the country, in order to verify the cross-cultural validity of this instrument and achieve its generalization.