1. Introduction

Dementia is an illness characterized by severe disturbances in functional, emotional, and cognitive capabilities. It is generally progressive and requires increasing assistance from caregivers (Johannessen et al., 2015). In Spain, the estimated prevalence for dementia is 18.5% of the population over 65, and 45.3% of the population over 85 suffer from dementia (Vega Alonso et al., 2016). Thus, 400000 to 600000 Spaniards may suffer from dementia (de Pedro-Cuesta, 2009). Informal caregivers are in charge, in addition to routine care, of many instrumental tasks like medical surveillance, administering medication, managing medical crisis and symptoms, making decisions, dealing with health services, and using medical equipment, but they also provide emotional support to the patient (de la Cuesta Benjumea, 2009). Providing care to a family member with dementia is associated with an emotional, physical, and financial burden due to its influence on lifestyle, career, and financial status. Thus, being a caregiver has proven to be a risk factor for depression, anxiety, and distress (Johannessen et al., 2015; Warchol et al., 2014). There is extensive literature describing the daily and cumulative stress, physical tension, and mental burden faced by caregivers. Moreover, it is proposed that objective stressors (helping with care) are related to subjective stressors (feelings of burden) and that these lead to intrapsychic stress and a significant and progressive re- duction in the caregivers’ well-being, satisfaction, and quality of life (Fauth et al., 2016). In fact, Dempsey et al. (2020) warned that, without adequate support for care providers and improved community social services, the continued burden that family members endure can make care unsustainable in the long run. Lacking social support and personal relationships is also related to social isolation and loneliness. Social isolation entails living without companionship, having little social contact, little support and feeling lonely, and is associated to poorer health, quality of life, life satisfaction, wellbeing, and community involvement (Hawthorne, 2006). Loneliness is experienced by a significant number of care- givers (Huertas-Domingo et al., 2021).

Nevertheless, research has proposed a shift in focus in recent years, offering a less pathologizing insight into caregivers more focused on analyzing the capabilities and strengths that can operate as protective factors against prolonged stress, that is, learning and positive adaptation within a conflicting or adverse environment (Crespo & Fernández-Lansac, 2015). Specifically, family caregivers require social support to improve their caring experience. This support consists of personal interaction, guidance, feedback, tangible help, social interaction, information, and training to help caregivers understand their role (Flórez et al., 2012). Subsequently, Bangerter et al. (2019) demonstrated the importance of relying on formal resources, which allow caregivers to distance themselves a little from their role and take time and space for themselves, as well as respite from care, thereby reducing exhaustion and burden, as well as increasing the levels of well-being and satisfaction. At the same time, professionals’ emotional support has been shown to generate positive effects on the family’s mood. Feeling understood, respected, and well-advised leads to positive levels of self-esteem and helps to contain negative emotions. In the same line, Wawrziczny et al. (2017) reported that caregivers of people with cognitive impairment or dementia express the need to be accompanied by specialized health care professionals and to have more space and leisure time, so they can reduce the burden generated by care. Furthermore, Ong et al. (2018) show that caregivers who benefit from social resources experience high satisfaction and positive care performance, although in most cases show poor physical and psychological health in care providers. This disparity can be explained through factors that may influence caregiver outcomes, such as recoverability, coping strategies, or social support. Social support buffers stress, and the availability of perceived social support leads to the lessening perceived stress and burden (Gellert, 2018; George et al., 2020; Kent et al., 2020). A meta-analysis of subjective burden in caregivers by del-Pino-Casado et al. (2018) shows that there is a negative association of perceived social support on subjective burden.

Delving into the importance of formal resources, Bangerter et al. (2019) stated that they allow caregivers to take time and space for themselves and distance themselves a little from the tasks involved in care, thereby reducing symptoms of burden and exhaustion and increasing well-being and satisfaction. This study showed that the use of a formal resource such as a day-care center was associated with lower general levels of captivity, whereby caregivers eventually understand the normality and benefits of delegating care and of making use of respite for oneself. Delegating care to external resources offers normality and freedom to care providers and, in turn, perceived social support and satisfaction. Additionally, a systematic review of the factors associated to burden in caregivers by Chiao et al. (2015) reports that cohabitation with the patient is associated to experiencing greater burden, which argues in favor of the benefits of formal resources. Similarly, Maseda et al. (2015) found that using day care centers helps caregivers reduce depressive symptoms and increases their subjective well-being.

Therefore, this study hypothesizes that the indicators of satisfaction, perception of support, and coping will be higher in caregivers who make use of formal resources. Specifically, three hypotheses were developed to be tested. Hypothesis 1: adjustment indicators (positive coping strategies, social support) will positively predict caregiver satisfaction. Hypothesis 2: adjustment indicators (positive coping strategies, social support) will negatively predict caregiver burden. Hypothesis 3: adjustment indicators and satisfaction will be higher, and burden and isolation will be lower in those caregivers who make use of formal resources compared to those who are only supported by an informal social media.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

The sample of the study is composed of 260 caregivers. Of these, 157 participants were caregivers who used social media, allowing them to be in contact with other caregivers or professionals, but who did not use the resources used by the other participants (day-care center or residential center); 40 participants were caregivers of people attending a day-care center; 63 participants were caregivers of people living in a residential center.

2.2. Measures

The data of interest were obtained through a data collection protocol consisting of the following scales: Demographic Questionnaire (Author elaboration). Relevant questions about sex and age of the respondents, such as their occupational and marital status, the length of time and frequency they had provided care for, and the severity of the condition of the person under their care.

Duke-UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire (Bellón et al., 1996). This measure of perceived emotional (“I have people who care what happens to me.”) and confidant social support (“I get useful advice about important things in life.”) is 11 items long and is rated on a Likert response scale ranging from 1 (much less than I want) to 5 (as much as I wish). Cronbach’s alpha for this scale in the current study was .96.

Friendship Scale (Hawtorne, 2006). This is a selfadministered instrument that provides reliable results of possible levels of social isolation with only six items. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (Never ) to 5 (Almost always). A sample item from this questionnaire was “I found it easy to get in touch with others when I needed to”. We obtained a low Cronbach’s alpha score for this scale (α = .44), possibly due to the small number of items and the heterogeneity of the sample (in this sense, for caregivers who benefited from residential centers, Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .63, dropping for the other two groups who had very varied backgrounds).

Satisfaction with Life subscale (Hahn et al., 2010). This 9-item scale is rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (Never ) to 5 (Always) and measures subjective well-being (i.e., “I am satisfied with my level of social activity”). It showed a high reliability (α = .94) in the current study.

Zarit Caregiver Burden Scale (Martín et al., 1996). This instrument is the adapted and validated Spanish version of the Zarit’s Caregiver Burden Interview (CBI; Zaritet al., 1980). It consists of 22 items (i.e., “Do you feel embarrassed about your relative’s behavior?”), about the caregiver’s feelings when caring for another person, each of which is scored on a frequency scale ranging from 1 (Never ) to 5 (Almost Always) and with a total score ranging from 22 to 110. Cronbach’s alpha obtained with our participants for this scale was .91.

Coping Strategies Scale (COPE; Carver, 1997). The original COPE is an inventory to evaluate different forms of stress responses. Despite its completeness, it is difficult for participants to fill in due to its length. In 1997, Carver presented an abbreviated version of the COPE, which is currently used in health-related research. The Brief COPE consists of 14 subscales, two items each, constituting a final instrument of 28 items. The scales appraise coping through the following means: self-distraction, active coping, denial, substance use, use of emotional support, use of instrumental support, behavioral disengagement, venting, positive reframing, planning, humor, acceptance, religion, and self-blame. Items (i.e., “I got emotional support from others” or “I learned to live with it”) are presented in terms of the action/response to a difficult situation, which people rate on a 4-point ordinal scale, ranging from 0 (I never do this) to 3 (I always do this). Its reliability in the present study was acceptable (α = .83).

2.3. Procedure

Participants were contacted at day-care and residential centers directly by the first author, who had access to these resources through professional practice. Participants who provided caregiving at home and only had access to online resources were contacted through a caregiving support website ran by the first author. Once contacted, participants were given a consent form indicating the study’s purpose, that it was anonymous and confidential, that they could withdraw from it at any time, and that it entailed completing a number of questionnaires. They were provided with an e-mail address in case they had any query about the study at a later time. After signing the consent form, they responded to the questionnaires of the study in either paper, pencil or online format. The study obtained the approval of the authors’ university ethical committee (code number CE302016).

2.4. Data Analysis

A descriptive analysis was carried out to account for the characteristics of the different groups of caregivers. Additionally, we tested for group differences in burden, isolation, satisfaction, social support, and coping using one-way ANOVAS. These analyses were performed with SPSS 27. Finally, a Structural Equation Model (SEM) using AMOS 27 was developed to test the differential effect for each group of help-seeking and social support on satisfaction and burden. r 2, RMSEA, CFI, and NFI were used as fit indexes. To check for differences in the SEM between groups, 𝑥-tests were calculated for the different parameters in the model.

3. Results

3.1 Descriptive Analysis

Caregivers with social media resources: 82.2% were women (129 women vs. 28 men), with a mean age of 60.71 years (SD = 18.89). Most caregivers (76.4%) lived with the affected relative, 33.1% were married, and 65% of them were caring for their mothers. Regarding occupational status, 33.1% were working, 27.4% were unemployed, 29.9% were retired, and 9.6% stated that their main occupation was housekeeping. As stated by participants, the individual with dementia condition under their care was moderate in 49% of the cases, light in 12.7% of the cases, and severe in 38.2% of the cases. Most were full-time caregivers (61.1%) or provided care for several hours a day (31.8%).

Caregivers using a day-care center resource: 70% were women (28 women and 12 men), with a mean age of 60.48 years (SD =13.22). Among them, 72.5% of participants lived with the affected relative, 65% were married, and 50% of them were caring for their mothers. As for their occupation, 42.5% were working, 10% were unemployed, 40% were retired, and 7.5% were housekeepers. The stage of dementia for the relative under their care was most often moderate (72.5%). This condition was light 15% of the times and severe the remaining 12.5%. Most (45%) spent several hours a day with the person they cared for and 40% did it full-time.

Caregivers using residential center resource: 68.3% were women (43 women and 20 men), with a mean age of 59.11 years (SD =13.72). Most of them were married (61.9%) and in 57.1% of the cases the affected person was the caregiver’s mother. As regards their occupation, 44.4% were working, 12.7% were unemployed, 33.3% were retired, and 9.5% were housekeepers. Dementia condition of the care recipient was either moderate (61.9%) or severe (38.1%). Since their relatives were at residential centers, we did not compute the frequency of care for this group. Table 1 shows how long participants in each group had been caregivers for:

3.2 Analysis of Variance

An ANOVA was performed to determine group differences between the participants caring for their relatives at home (social-media group) compared to those in a day-care center or a residential center. Table 2 shows the differences between groups in the study variables:

All variables in the ANOVA showed group differences. In the case of burden, post-hoc tests indicated significant differences between the social-media group and the residential-center group. There were no differences between these two groups and the group that used the day-care center. The group of participants whose relatives lived in residential settings experienced less burden, especially compared to participants who cared for their relatives at home (social-media group).

We also found significant differences in social isolation depending on the group of participants. Scheffé’s test showed significant differences between the group that only used the social media resource and the groups with day-care resources and residential resources. The day-care group scored highest in social isolation; the social-media group showed the lowest score, showing a greater degree of social isolation.

Concerning satisfaction, the post-hoc tests indicated significant differences between the social media group, the day-care group, and the residential group. Thus, people whose family member was in a residence had higher life satisfaction than the people who cared for their family member at home (social-media group).

As for received social support, post-hoc tests indicated significant differences between the social-media group of caregivers and the groups using external resources. The day-care group presented the highest levels of perceived social support, followed by the residential group, with a large difference compared with participants using social media, who had considerably lower levels of social support.

As regards active coping, post-hoc tests showed differences between the social-media group and the daycare group. People who used a day-care center had higher active coping compared to people who only received help online (social-media group).

Finally, significant differences were found for helpseeking between the social media support group and the groups using a day-care center and a residential center. A considerable difference was observed between the daycare group and the residential group, compared with the social-media group. The day-care group scored highest in help seeking.

Table 2. One-way ANOVA for Differences between Groups

| Group | ||||||||

| Social Media | Day Care | Residential | ||||||

| F(2,257) | η2 | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Burden | 7.80* | .06 | 2.78a | .80 | 2.70 | .76 | 2.33a | .66 |

| Social Isolation | 36.63* | .22 | 3.08ab | .81 | 4.01a | .82 | 3.91b | .76 |

| Satisfaction | 64.38* | .33 | 2.29ab | .84 | 3.23ac | .89 | 3.68bc | .92 |

| Social Support | 71.03* | .36 | 2.14ab | .99 | 3.69a | 1.05 | 3.65b | 1.02 |

| Active Coping | 8.37* | .07 | 1.75ab | .78 | 2.24a | .60 | 2.05b | .74 |

| Help Seeking | 17.81* | .12 | 1.31ab | .70 | 1.96a | .76 | 1.73b | .63 |

Note. *p<.001.abcSignificant differences (p<.001) between groups marked with the same letter using Scheffé’s test.

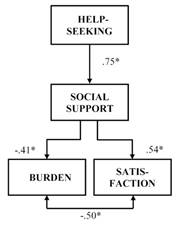

Figure 1 Structural equation model for the prediction of satisfaction through social support, help-seeking, and burden in the social-media caregivers. Note. Model: χ2(6, N = 157) = 10.88, p = .09; RMSEA = .056 (CI 90%: .001-.109), CFI = .986, NFI = .971. *p < .01.

Figure 2 Structural equation model for the prediction of satisfaction through social support, help-seeking, and burden in day-care caregivers. Note. Model:χ2(6,N= 40) = 10.88,p=.09; RMSEA= .056 (CI 90%: .001-.109), CFI = .986, NFI = .971.*p<.01.

3.3. Structural Equation Model

Below are the SEM models developed for each group of participants, which showed the results of each variable and how they were related in the prediction of satisfaction. A SEM was carried out to determine the role of help seeking coping and social support in the prediction of satisfaction and burden in the three types of participants, based on the type of care received by the dependent: at home, in a day center, and in a residential setting. The model achieved a very acceptable level of fit and showed that, for participants with relatives living in a residential setting or using a day-care center, help-seeking coping is significantly determined by the social support received, and this social support has an effect on burden and satisfaction. However, in the case of participants who care for the family member at home, social support had an impact on satisfaction, but not on burden. Help-seeking also showed a significant indirect effect on satisfaction for the residential center group (r = .54, p < .01), day-care group (r = .41, p < .01), and social media group (r = .43, p < .01). Regarding burden, help seeking showed a significant indirect effect for the residential center group (r = .37, p < .01), day-care group (r = .31, p < .01), but not for the social media group. Additionally, critical ratios for differences showed that the social-media group differed in the social support and burden relationship from the residential care (𝑥 = 3.27, p < .01) and day-care group (𝑥 = 2.18, p < .05). Social support impacted much less in burden for the social media group in comparison with the two other groups.

4. Discussion

Social support is one of the issues that has aroused great interest for decades, due to the positive impact it has on wellbeing, especially for individuals who are in the most vulnerable life circumstances when they must deal with internal and external stressors (Barrón, 1996). At the same time, being a caregiver for a person with dementia has proven to be a risk factor for depression, anxiety, distress, and social isolation. In fact, this situation has been shown to produce chronic stress and burden involving the whole family. The psychological implications of this situation have been widely evidenced in the literature, highlighting symptoms of anxiety and depression, low levels of well-being, and physical problems associated with stress.

Consequently, as Pérez and Yanguas (1998) suggested, it is essential to involve the caregiver in educational programs, which should include information and knowledge about the pathology they are dealing with, including its development and symptoms. It should also provide information on how to care for oneself, symptom prevention, and correct action guidelines, as well as the available social resources, as one more form of support and help, and how to have access to them. Therefore, this study has sought to approach an undeniable daily reality and show the benefits of social resources for a population that increases every day.

Our results support our first hypothesis, which proposed that the indicators of adaptation (positive coping strategies, social support) will positively predict caregivers’ satisfaction. The results concur with Ong et al. (2018), who state that recoverability, coping strategies, and help-seeking lead to satisfaction. Theyare also in line with Zhao et al. (2014) and Trepte et al. (2015), who reveal that people who have a high degree of social support will also have a more satisfactory life and will therefore score higher in levels of personal and social well-being.

We also found support for our second hypothesis, which stated that the adjustment indicators (positive coping strategies, social support) will negatively predict caregiver burden, and, as our SEM model shows, the correlations between the two variables are negative. These data, in turn, are consistent with the theory of Gellert (2018), which presents the buffering effect of social support on stress and burden. In this line, Andrén and Elmstahl (2005) and Carretero et al. (2006) note researchers’ growing interest in the rewards and satisfaction associated with care and the reduction of burden through them.

The third hypothesis, indicating that the adjustment and satisfaction indicators will be higher, and burden and isolation will be lower in caregivers who make use of formal resources compared to those supported only by an informal social media, is also supported by our data. Our ANOVA results show significant differences between caregivers who only use social media and caregivers who use the formal resources (either day-care center or residential center). The latter show less burden and social isolation and higher positive coping, social support, and satisfaction, congruent with previous research results (Argentzell et al., 2014; Chiao et al., 2015; Phillipson & Jones, 2012). Additionally, the SEM model indicates that while social support shows a strong negative relationship with burden for the day-care and residential care groups, this relationship is significantly smaller for the social media group, showing that social support does not attain the same level of relief for people who provide care exclusively at home. These results are coherent with García and Ceballos (2002), who, by highlighting the importance and benefits of formal resources, explain that the emotional support that professionals provide can have a beneficial effect on the family and caregiver situation. The mere release from care duties that formal resources provide, even for a few hours (day-care centers), has a positive impact on caregivers’ well-being (Maseda et al., 2015).

Some cautionary notes should be raised regarding these results since there are a number of limitations in the current study. Firstly, the sample size was not as big as desirable, especially in the residential care and day care group, which limits our conclusions. Also, this study was cross-sectional, and caregivers were at different experiential stages, so we cannot offer the long-term picture that a longitudinal study would provide. The variables included in the study attempted to provide a wide perspective on issues related to caregiving; nevertheless, emotional, cultural or religious variables were left out of the study. Additionally, we did not consider in our model the objective burden (time, effort, and resources spent in caregiving) but rather the subjective burden. Neither we considered the material resources available to provide care. A comprehensive model including these types of variables would provide better insight on the interplay between social support, coping, isolation, burden, and satisfaction.

In conclusion, this research reflects the importance of formal resources in the lives of caregivers and the benefits they generate throughout the course of the pathology, and, thus, the need to increase knowledge and access to such resources in today’s society. This work has sought to add a more in-depth view to a field that, while already delving into social support, is still very limited concerning the social resources and interventions that provide it. It is particularly interesting to note that the deficiency in the promotion of support resources continues to be a pending subject, both in public institutions and private entities working in this sector.

Finally, we emphasize that developing new resources to aid family members, relatives, and caregivers of people with cognitive impairment and dementia not only has a direct and positive impact on the health of these people, but is also useful to establish a safety net for these medical conditions that, due to the emergence of degenerative pathologies, have an impact on the affected person as well as on their support network. Therefore, supporting caregivers and bringing the social resources closer to them indirectly improves the informal response offered to people with dementia (promoting quality of care to maintain, if not improve, their quality of life). Similarly, supporting caregivers means investing long term in the reduction in social and health costs arising from perceived burden. Finally, supporting caregivers means recognizing the depth of the issues affecting the public health of contemporary societies as a first step to find solutions.