1. Introduction

Psychology has traditionally addressed and dealt with the diagnosis and treatment of different psychopathological conditions. However, in the last decades, the interest in studying well-being has been renewed, presenting two periods of noticeable rise. The first period, since 1960, came about due to the incorporation of subjective assessments into the life quality construct, which, until then, had only taken into consideration the objective conditions related to well-being. The second one started in the beginning of the 21st century, with the onset of Positive Psychology (Ryan & Deci, 2001). In turn, research on well-being has been divided into two main currents, whose origins can be traced back to Philosophy. On the one hand, to hedonic philosophical tradition, according to which well-being is reached through pleasure and enjoyment. On the other hand, to eudaemonic tradition, according to which well-being stems from virtue and fulfilment of personal potential. It should be noted that both currents have been operationalized through different constructs, known as subjective well-being and psychological well-being, respectively (Huta & Waterman, 2014).

For decades, both lines have developed independently. However, since that fragmentation has created limitations to the understanding of the concept, unilateral approach to the study of well-being is currently not advisable (Huppert, 2014). Likewise, complementarity of both approaches is suggested, indicating that they would represent complementary aspects of well-being (Disabato et al., 2016; Longo et al., 2016).

It was in this context that the study of flourishing began. Although there is no consensus as to its definition, it is said that it would involve both hedonic and eudaemonic elements and that it would be characterized by being a dynamic phenomenon, including continuous update of the human potential and giving place to an optimal state of mental health (Wolbert et al., 2015).

It is worth noting that, although it is possible to identify different approaches that attempt to explain human flourishing (Agenor et al., 2017; Huta & Waterman, 2014), the model proposed by Positive Psychology has captured the interest of several researchers (Butler & Kern, 2016). From this model, known by the acronym PERMA, it is proposed that well-being is a dynamic state of optimal psychosocial functioning that facilitates the flourishing of people (Butler & Kern, 2016). According to Seligman (2011), the combined development of the five components or pillars of well-being would bring forth flourishing. The first pillar corresponds to positive emotions, understood as those hedonic-like affections associated with enjoyment and happiness. The second aspect, named engagement, refers to the aware and committed involvement in different activities. For its part, the third component refers to positive relationships, associated with quality and availability of social bonds. The fourth pillar is meaning, understood as the connection to a higher purpose that transcends self interest. Lastly, the fifth aspect is achievement and it describes the ability to work with discipline and effectiveness for the accomplishment of personal goals, while keeping a high level of motivation and completing the different tasks assigned.

Seligman (2011) suggests that, although the model is promising, its measurement might be complex due to its multidimensional structure. However, Butler and Kern (2016) have designed a scale named PERMA Profiler, which allows the measuring of flourishing by operationalizing the five proposed pillars. It is worth mentioning that the scale has been translated and adapted in different countries, finding a greater number of adaptations for the adult population (Cobo-Rendón et al., 2020; de Carvalho, 2021; Demirci et al., 2017; Elfida et al., 2021; Giangrasso, 2021; Pezirkianidis et al., 2019) than for the adolescent one (Singh & Raina, 2020). Likewise, although there are studies where the five pillars of flourishing have not been identified (Ryan et al., 2019), the replication of the factorial structure of the original scale stands out in the available adaptations (CoboRendón et al., 2020; Elfida et al., 2021; Giangrasso, 2021; Pezirkianidis et al., 2019; Wammerl et al., 2019; Watanabe et al., 2018). It should be noted that in most cases, a clear and consistent structure is reported, although some authors report difficulties concerning the reliability of the engagement subscale (Bartholomaeus, et al., 2020; Pezirkianidis et al., 2019; Ryan et al., 2019).

Currently, although it is known that well-being presents evolutionary peculiarities (Vera-Villarroeletal., 2013), research on the topic regarding the first stages of life is scarce (Witten et al., 2019). Likewise, due to the fact that adolescence has been conceptualized as a problematic period in life, the study of optimal psychological functioning during this stage has been postponed. In this sense, developing models of mental health that foster the full development of people from early stages is of fundamental importance (Giménez et al., 2010; Kern et al., 2016).

Finally, considering that the factors involved in wellbeing could vary according to the socio-cultural context (Diener et al., 2017), it is necessary to contrast the model in various countries empirically, with the objective of knowing the extent of the theorical proposal (Khaw & Kern, 2014).

Based on the mentioned context, the aim of this study was to psychometrically adapt the PERMA Profiler Scale (Butler & Kern, 2016) for the adolescent population in Argentina.

2. Method

This research is instrumental, with a non-experimental, cross-sectional design (Montero & León, 2007).

2.1 Participants

Six expert judges, specialized in the field of positive psychology and psychological assessment, participated in the review of the items, along with a pilot sample of 21 adolescents from 12 to 18 years old (M = 14.8; SD = 1.9).

For its part, the sample of typification was non-probabilistic and consisted of 421 Argentinian adolescents (63.7% female), aged 12 through 19 (M = 14.9; SD = 1.75), who attended secondary public schools (59.8%) and private schools (40.2%) from urban regions of Argentina.

2.2 Instruments

PERMA Profiler Scale (Butler & Kern, 2016). The instrument under revision was the PERMA Profiler version translated in this study (Butler & Kern, 2016). It was originally designed for English-speaking adult population and it consists of 23 items that are answered in a Likert scale of 11 points. Each PERMA domain is assessed through three items. Likewise, eight additional items are included to assess aspects that are considered as linked to flourishing: negative emotions, physical health, loneliness, and happiness. The authors consider that these aspects interrupt the answering trends and prevent the inclusion of elements with inverse scoring. In addition, they suggest that said aspects provide relevant information, since the salutogenic approach does not deny the impact they have on mental health.

The internal structure of the PERMA Profiler scale has been studied through exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis, yielding satisfactory fit indices (χ 2(80) = 10.61; CFI = .97; T LI = .96 RMSEA = .06; SRMR =.03) for the five-factor model in adult population (Butler & Kern, 2016). Regarding internal consistency, Alpha coefficients between .72 and .90 are reported for the subscales and .94 for the full scale.

Ryff’s Psychological Well-Being Scale (Meier & Oros, 2019). It assesses psychological well-being through 20 items that are answered in a Likert scale of five points. In the adaptation made for Argentinian adolescents, four factors emerged: personal growth and purpose, autonomy, self-acceptance, and positive relationships. Said structure was verified through a confirmatory factor analysis. Cronbach’s Alpha presented coefficients between .64 and .77 in the different subscales.

Satisfaction With Life Scale (Castro Solano, 2000). It assesses the level of satisfaction with life in a unidimensional way, through five items that are answered in a Likert scale of six points. In the adaptation made for Argentinian adolescents, an Alpha of .75 was obtained for the full scale.

Meaning in Life Questionnaire (Góngora & Castro Solano, 2011). It assesses the meaning of life and it consists of 10 items that are answered through a Likert scale of seven points. In the adaptation made for Argentinian adolescents, the scale is composed of the dimensions search of meaning and presence of sense, with Alpha indexes of .82 y .79, respectively.

2.3 Procedure

The expert judges were invited to participate through an e-mail, in which they were asked to value the fit of the translation of the items, their syntactic and semantic adequacy, and the theorical coherence of the content of each statement with the corresponding dimension.

Following, the pilot sample of adolescents was selected by convenience, seeking that all the ages of the proposed range were represented. Parents and adolescents were asked for an informed consent. Each adolescent received a copy of the scale with the instruction of reading the items and expressing if they were understandable. In addition, they were asked to value the clarity of the instruction and the answer options.

In order to select the sample of typification, personal contact was established with schools, explaining the aim of the research and asking the authorities for permission. Participation was voluntary, anonymous, and confidential. As inclusion criteria, the following aspects were considered: (1) the adolescents must have been enrolled in school, (2) they must have been between the ages of 12 and 20, (3) they must have had their parents’ authorization, and (4) they must have given their consent for participation. The data collection was conducted through a virtual form.

2.4 Data Analysis

In the first place, a translator translated the items of the PERMA Profiler scale (Butler & Kern, 2016) from English to Spanish, trying to keep their content as accurate as possible. It should be noted that the meaning of the statements was translated functionally rather than literally, considering the expressions used by the population under study to ensure the comprehension of the text.

Following, the items were submitted to revision by the expert judges. Each specialist received the original scale in English, the translated version, and a conceptual definition of each pillar of flourishing, specifying through which items these were being operationalized. A few modifications were made to the wording as a result of their suggestions. The agreement among the specialists was assessed through the Aiken’s V coefficient. The version that was reviewed by the judges was administered to a pilot sample of adolescents. Finally, the version that was adjusted in accordance with the previous procedures was administered to the typification sample.

Descriptive analysis of the items in the answers given by the 421 adolescents were carried out, and the discriminatory capacity was assessed through the corrected homogeneity index. Regarding the study of internal structure, a confirmatory factor analysis was conducted using the Lavaan package (version 0.6-8) in R (version 4.1.0). The fit of the model was evaluated through the goodness of fit used for the original version of the scale (Butler & Kern, 2016): the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), the Tucker Lewis Index (T LI), and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI).

For its part, internal consistency was analyzed through Cronbach’s Alpha coefficients, calculated through the DescTools package (version 0.99.41) in R (version 4.1.0). Finally, to study the concurrent validity, Pearson’s r correlations were estimated between each factor of the scale and the scores obtained in the dimensions of Psychological Well-Being Scale (Meier & Oros, 2019), the Meaning in Life Questionnaire (Góngora & Castro Solano, 2011), and the Satisfaction With Life Scale (Castro Solano, 2000), using the Hmisc package (version 4.5-0) in R (version 4.1.0).

3. Results

3.1 Content Validity

From the evaluation of the items conducted by the experts, 14 items were kept untouched and 9 were slightly modified in their wording. For instance, the item In general, how happy do you feel? was modified to “In general, how often do you feel happy?”, and the item “How often are you capable of dealing with your responsibilities?” was changed to “How often are you capable of fulfilling your responsibilities?”. Regarding the level of agreement among the judges, all the items obtained an Aiken’s V ranging from .8 to 1, indicating a high level of agreement concerning the content validity (Aiken, 2003; Ato et al., 2006).

Then, the scale was applied to a pilot sample of adolescents. No difficulties in understanding the instructions, the statements or the answer options were identified. The version to be administered to the typification sample consisted of 23 items.

3.2 Descriptive Analysis of the Items

The values of skewness and kurtosis were not higher than the figures of 2 recommended to perform parametric analyses (Bandalos & Finney, 2010). On the other hand, no missing cases were identified (see Table 1).

3.3 Discriminatory Power of the Items

It was found that all the items have an adequate discrimination capacity, with corrected item-total correlations higher than .30 (Martínez Arias, 2005).

3.4 Construct Validity

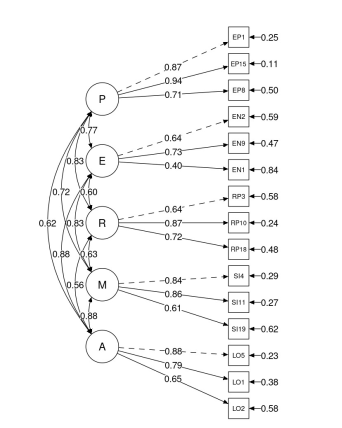

As proposed by Butler and Kern (2016), the results of the confirmatory factor analysis suggested an acceptable fit of the five-factor model proposed by the authors of the scale (see Table 2). It was observed that all the items presented a significant weight (p < .001) equal to or higher than .40 in the factor to which they belong, and that correlations among the dimensions range between .56 and .88 (see Figure 1).

3.5 Internal Consistency

Alpha coefficients of .87 were observed for positive emotions, .62 for engagement, .78 for positive relationships, .81 for meaning, and .82 for achievement. The full scale obtained an Alpha of .92.

3.6 Concurrent Construct Validity

As expected from the theoric point of view, positive and significant correlations were observed among all the dimensions of flourishing and psychological well-being, satisfaction with life, and presence of meaning in life. On the contrary, the null or inverse correlation presented between the pillars of flourishing and the dimension search for meaning is very weak.

Table 1 Descriptive statistics of the PERMA Profiler Scale

| Item | Mean | SD | Skewness | SD | Kurtosis | SD |

| 1. In general, how often do you feel happy? | 6.84 | 2.06 | −.588 | .119 | −.038 | .237 |

| 2. How often do you feel absorbed or focused in what you are doing? | 6.55 | 2.14 | −.554 | .119 | .024 | .237 |

| 3. To what extent do you receive help and support from other people when you need it? | 7.05 | 2.53 | −.723 | .119 | −.281 | .237 |

| 4. In general, to what extent do you feel that you lead a life with purpose and meaning? | 6.78 | 2.66 | −.744 | .119 | −.208 | .237 |

| 5. How often do you feel that you are advancing to accomplish your goals? | 6.68 | 2.56 | −.850 | .119 | .092 | .237 |

| 6. In general, how often do you feel anxious? | 6.78 | 2.64 | −.747 | .119 | −.264 | .237 |

| 7. In general, how would you define the state of your health? | 8.02 | 2.01 | −1.10 | .119 | .708 | .237 |

| 8. In general, how often do you feel optimistic? | 6.58 | 2.40 | −.658 | .119 | −.184 | .237 |

| 9. In general, how interested or excited do you usually get about things? | 7.51 | 2.03 | −1.09 | .119 | 1.22 | .237 |

| 10. To what extent do you feel loved? | 7.70 | 2.15 | −1.05 | .119 | .851 | .237 |

| 11. In general, to what extent do you feel that what you do in life is valuable and worth the effort? | 6.81 | 2.46 | −.859 | .119 | .287 | .237 |

| 12. How often do you reach the important goals you set for yourself? | 6.79 | 2.48 | −.927 | .119 | .328 | .237 |

| 13. In general, how often do you feel angry? | 5.39 | 2.55 | −.216 | .119 | −.868 | .237 |

| 14. How satisfied are you with your current physical health? | 6.71 | 2.81 | −.788 | .119 | −.257 | .237 |

| 15. In general, how happy do you feel? | 7.06 | 2.19 | −.767 | .119 | .191 | .237 |

| 16. How lonely do you feel in your daily life? | 4.43 | 3.04 | .113 | .119 | −1.20 | .237 |

| 17. How often do you lose track of time when you are doing something you enjoy? | 8.00 | 2.25 | −.1.28 | .119 | 1.15 | .237 |

| 18. How satisfied are you with your personal relationships? | 7.49 | 2.32 | −1.08 | .119 | .931 | .237 |

| 19. To what extent do you know what you want for your life? | 6.81 | 2.56 | −.134 | .119 | −.098 | .237 |

| 20. How often are you capable of fulfilling your responsibilities? | 7.36 | 2.22 | −.826 | .119 | .295 | .237 |

| 21. In general, how often do you feel sad? | 5.04 | 2.56 | .016 | .119 | −.967 | .237 |

| 22. Compared to other people your age and gender, how is your health? happy are you? | 7.58 | 2.27 | −1.12 | .119 | .736 | .237 |

| 23. Considering all the aspects of your life, how happy are you? | 7.69 | 1.98 | −1.09 | .119 | 1.11 | .237 |

Table 2 Fit indices of the model

| χ2 | χ2/d.f. | CFI | T LI | RMSEA[IC] | SRMR | |

| PERMA Model | 296.806 | 3.71 | .94 | .92 | .08 [.07,.09] | .04 |

Note. Method of extraction: Maximum reliability.

On the other hand, there are negative correlations between the items of negative emotions and loneliness included in the PERMA Profiler Scale and all the dimensions of psychological well-being, satisfaction with life and meaning in life, except for the dimension search for meaning. Regarding self-perceived physical health, a positive and significant correlation is detected with all the dimensions, except for the search for meaning. Lastly, the item of general happiness positively and significantly correlates with all the dimensions of well-being, satisfaction, and presence of meaning. A negative link with the search for meaning was detected (see Table 3).

Table 3 Correlations for evidence of concurrent validity

| Self-acceptance | Positive relationships | Autonomy | Growth and purpose | Satisfaction with life | Presence of meaning | Search for meaning | |

| Positive emotions | .63**a (1 − β = 1) | .36**m (1 − β = .99) | .33**m (1 − β = .99) | .31**m (1 − β = .99) | .69**a (1 − β = 1) | .45**m (1 − β = 1) | −.04 |

| Engagement | .45**m (1 − β = 1) | .09 | .13*b (1 − β = .76) | .45**m (1 − β = 1) | .54**a (1 − β = 1) | .47**m (1 − β = 1) | .07 |

| Positive relationships | .5**a (1 − β = 1) | .5**a (1 − β = 1) | .27**b (1 − β = .99) | .22**b (1 − β = .97) | .61**a (1 − β = 1) | .34**m (1 − β = .99) | -.13**b (1 − β = .53) |

| Meaning | .57**a (1 − β = 1) | .18**b (1 − β = .87) | .25**b (1 − β = .99) | .57**a (1 − β = 1) | .62**a (1 − β = 1) | .71**a (1 − β = 1) | .00 |

| Achievement | .53**a (1 − β = 1) | .15**b (1 − β = .69) | .25**b (1 − β = .99) | .56**a (1 − β = 1) | .59**a (1 − β = 1) | .5**a (1 − β = 1) | .04 |

| Negative emotions | -.34**m (1 − β = .99) | -.32**m (1 − β = .99) | -.40**m (1 − β = 1) | -.06 | -.27**b (1 − β = .99) | -.08 | .30**m (1 − β = .99) |

| Self-perceived physical health | .55**a (1 − β = 1) | .26**b (1 − β = .99) | .33**m (1 − β = .99) | .28**b (1 − β = .99) | .62**a (1 − β = 1) | .32**m (1 − β = .99) | -.08 |

| Loneliness | -.36**m (1 − β = .99) | -.44**m (1 − β = 1) | -.29**b (1 − β = .99) | -.10*b (1 − β = .53) | -.32**m (1 − β = .99) | -.15**b (1 − β = .70) | .20**b (1 − β = .94) |

| General happiness | .62**a (1 − β = 1) | .29**b (1 − β = .99) | .26**b (1 − β = .99) | .36**m (1 − β = .99) | .69**a (1 − β = 1) | .46**m (1 − β = 1) | -.06 |

Note. *Sig. < .05; **Sig. < .01; =small effect size (.10), b=medium effect size (.30), c=large effect size (.50).

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to adapt the PERMA Profiler Scale (Butler & Kern, 2016) psychometrically for the population of Argentinian adolescents.

Firstly, the content validity and the functioning of the items translated into Spanish were assessed, providing empirical evidence in each case. Agreement was observed between the expert judges who evaluated the adequacy of the items, and it was detected that all the statements discriminated in a satisfactory way, indicating that if subjects scored high or low in a specific item, this would also be the trend in the full scale. When verifying the internal structure of the scale, it was observed that all the items presented significant saturations in the factor to which they belonged and that correlations among the dimensions ranged in values similar to those reported in other validations of the scale (Cobo Rendón et al., 2020; Giangrasso, 2021; Pezirkianidis et al., 2019). Likewise, although the model’s goodness of fit indices and the error presented marginal values, as compared to the ones recommended nowadays (Greiff & Heene, 2017), literature holds that these would indicate an acceptable fit (Cupani, 2012; Kline, 2011). In the same manner, it is observed that the fit indices obtained in this study are comparable to those presented in other validations of the scale for adults (Pezirkianidis et al., 2019) and even higher than those observed in adaptations for adolescents (Singh & Raina, 2020).

Regarding reliability, it was observed that all the items contributed to internal consistency. Only the dimension engagement obtained a score lower than .70 (α = .62). It is worth mentioning that said dimension has also shown weak psychometric properties in other adaptations of the scale (Demirci et al., 2017; Giangrasso, 2021; Pezirkianidis et al., 2019). The previous could be owing to the differential understanding of the items based on the socio-cultural context or the nature of the construct. According to literature (Pezirkianidis et al., 2019), engagement may be manifested in various situations such as school activities, work-related activities or activities of another nature. However, the items included in the subscale do not refer to a specific context but to people’s general experience, providing a slightly specific perspective. Likewise, according to Pezirkianidis et al. (2019), it is not clear whether engagement in this subscale is understood as a construct different from flow, which is characterized by its multidimensionality and complexity (Schaufeli et al., 2002).

For their part, the results of this study regarding the concurrent validity showed that, according to what is theorically expected, the five pillars of flourishing correlate in a moderate, significant, and positive way with all the dimensions of psychological well-being and with satisfaction with life. Regarding the latter, some authors state that flourishing and subjective well-being, along with satisfaction with life as one of its main components, converge in a single factor of well-being (Goodman et al., 2018). In turn, other studies mention that there is a high correlation between psychological well-being and flourishing; the latter being considered as a conceptualization that is mainly eudaemonic (Giangrasso, 2021). In response to this, Seligman (2018) proposes that the PERMA model does not pretend to provide a new and completely different conceptualization of well-being, but to provide information concerning the individual composition of flourishing, allowing each person’s profile of well-being to be known. In this sense, the five proposed pillars would be associated both with hedonic and eudaemonic aspects, explaining the variability of flourishing in a more specific way.

It is worth mentioning that Butler and Kern (2016) agreedwiththecurrentdefinitionsofmentalhealth (World Health Organization, 2016), which suggest flourishing is much more than the absence of psychopathological symptomatology. Likewise, the authors point that the perspective of Positive Psychology does not ignore the importance of negative emotions, loneliness and self-perceived physical health in the vital experience. In this sense, the inclusion of the items assessing those aspects would provide relevant information for understanding well-being.

More specifically, although positive emotions would represent the hedonic aspects of well-being, from the tripartite model of subjective well-being comes the thought that both the positive affectivity as well as the negative one must be considered when assessing subjective well-being, since there would exist a link between people’s affective profile and their well-being (Diener & Emmons, 1984). Likewise, findings indicate that well-being is closely related to happiness, in accordance with the results of this study. In this sense, recent pieces of research state that positive emotions have a causal effect on well-being, both through biological as well as psychological ways (Le Nguyen & Fredrickson, 2017).

Regarding loneliness, several studies state, in line with what was reported in this study, that it would be associated with lower levels of well-being during adolescence (Houghton et al., 2016; Ronka et al., 2014), generating negative emotions that could trigger various psychopathological disorders (Houghton et al., 2016).

For its part, empirical evidence suggests that selfperceived physical health during adolescence is linked to the experience of well-being (Kern et al., 2016). Physical changes that take place during this stage could generate a distortion of the body image that would result in a negative and subjective evaluation of the body (Savi-Çakar & Savi-Karayol, 2015). In addition, findings in adult population indicate that body image has an impact on flourishing (Davis et al., 2020).

Regarding the relationship between the pillars of flourishing and the dimensions of the scale of meaning in life, it was observed that the presence of meaning is positively related to flourishing. Empirical evidence states that the presence of vital meaning consolidated during adolescence would have a strong relationship with wellbeing and satisfaction with life, and, at the same time, it would be a protective factor during this stage (Brassai, 2011). For its part, and in line with the findings of this study, it has been reported that the dimension search for meaning negatively and significantly correlates with satisfaction and with an index of general wellbeing in Argentinian adolescents (Góngora & Castro Solano, 2011). According to the authors, the presence of and the search for meaning are two subscales that measure different constructs and subscales that during adolescence have little relationship between them (Góngora & Castro Solano, 2011). In addition, Krok (2018) states that the search for a vital meaning would be linked to well-being only during early adulthood, once people find a meaning for their lives.

In conclusion, the adapted scale manages to adequately capture the five components of flourishing and it presents satisfactory psychometric properties, with a factor structure that is consistent with the original version of the instrument (Butler & Kern, 2016). The version for Argentinian adolescents was finally made of a total of 23 items, 15 of which operationalize the pillars of flourishing, and 8 of which provide complementary information.

4.1 Theorical and Practical Implications

This study presents theorical and practical implications. Firstly, it provides empirical evidence regarding the multidimensional model of flourishing proposed by Seligman (2011), promoting research on flourishing in the Latin American and Spanish-speaking context. Secondly, it provides a valid instrument, reliable and easy to administer, plausible of use in psychological practice so as to detect improvements in the different pillars of flourishing, to design interventions and to measure the effectiveness of different programs. It is necessary to highlight that, nowadays, considering children and adolescents’ perspectives when assessing their well-being (Ben-Arieh et al., 2014) is suggested and, in this sense, having a selfreport scale that captures different aspects of flourishing represents a valuable contribution.

4.2 Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

This study presents limitations. Regarding the sample, it has been selected out of convenience, which limits the possibility of generalizing the results. Regarding the analyses conducted, for future studies we recommend considering the possibility of assessing the scores’ stability and including new evidence of validity. Likewise, although the present study reports the correlation between the hedonic and eudaemonic aspects of well-being and flourishing, it would be useful to evaluate the impact these constructs have on the prosperity of adolescents.

Moreover, the operationalization of engagement should be revised, differentiating it from similar constructs and assessing its manifestation during adolescence.

It is recommended to continue with the study of the psychometric functioning of the scale in samples concerning different age groups, with the aim of evaluating the evolutionary particularities of flourishing throughout life. Lastly, the study of the psychometric functioning of the scale is suggested in samples of adolescents living in other countries, with the purpose of assessing the replicability of the model and the differential characteristics of flourishing based on the sociocultural context. Finally, it is suggested to test the predictive capacity of the scale and its link with opposite constructs and other health indicators, promoting the advancement of the science of well-being.