Introduction

Shift work has become increasingly common due to recent changes in economics and political trends. It is estimated that in industrialized countries, approximately 20% of jobs use this type of work modality (Tripartite Meeting of Experts on Working Time Arrangements ILO & International Labour Office, 2011). European and North American surveys reported that between 15 to 30% of the adult worker population is exposed to shift work (Alterman, Luckhaupt, Dahlhamer, Ward, & Calvert, 2013; Eurofound, 2012). According to the First National Survey of Health and Working Conditions in 2007, 29% of people in Colombia work in rotating shifts (Ministerio de la Protección Social, 2007).

Although the mechanisms explaining the impact of shift work on health are not fully understood, its effects have been extensively studied.

It has been reported that shift work is associated with cancer, diabetes, gastrointestinal disorders, metabolic and cardiovascular disease (Knutsson, 2003; Kubo et al., 2006; Lie, Roessink, & Kjaerheim, 2006; Mosendane, Mosendane, & Raal, 2008; Nojkov, Rubenstein, Chey, & Hoogerwerf, 2010; Pan, Schernhammer, Sun, & Hu, 2011; Wang, Armstrong, Cairns, Key, & Travis, 2011), and the proposed underlying mechanisms encompass circadian rhythm disruption, light at night, sleep deprivation, immune depression, lifestyle changes and stress (Boivin & Boudreau, 2014; Brondel, Romer, Nougues, Touyarou, & Davenne, 2010; Bushnell, Colombi, Caruso, & Tak, 2010; Crispim et al., 2011; Fritschi et al., 2011; Hansen, 2001). Specifically, in relation to healthcare work, in which non-regular and night work hours are commonly seen, there is evidence, most of it from studies in nurses, about how this type of job organization can affect workers in a negative way, both physiologically and psychologically (Admi, Tzischinsky, Epstein, Herer, & Lavie, 2008).

Work-related stress, defined as those aspects of work design, organization and management and their social and organizational context, that have the potential to cause harm to employee health (Harma, Kompier, & Vahtera, 2006) has been shown to be different between day workers and shift workers (Boggild, Burr, Tuchsen, & Jeppesen, 2001; Parkes, 1999; Tenkanen, Sjoblom, Kalimo, Alikoski, & Harma, 1997). Moreover, shift work and irregular work hours can interfere the work-life balance (Jansen, Kant, Nijhuis, Swaen, & Kristensen, 2004).

Studies addressing the association between shift work and work-related stress have not reached consensus; some of them have pointed out to that occupational stress is higher for shift workers when compared to day workers (Boggild et al., 2001; Dar tiguepeyrou, 1999; Harada et al., 2005; Parkes, 1999), while others have not found a significant difference (Knutsson & Nilsson, 1997). These differences may be explained by the type of stress measured, sample size, and coping strategies to eliminate or reduce occupational pressures.

Shift work and work-related stress are important exposures to be studied in the health care sector, and it seems that both show similar psychophysiological stress reactions, pathways to affect health status (Harma et al., 2006) and interference with social and family life (Demerouti, Geurts, Bakker, & Euwema, 2004; Simon, Kummer ling, Hasselhorn, & Next-Study, 2004).

In the present study we investigated the association between shift work and work-related stress symptoms, in health care workers from a clinical setting in Medellin, Colombia. To our knowledge, there is no other study investigating associations between stress symptoms and shift work among Colombian health care workers.

Methods

Study participants

This cross-sectional study was carried out in Clínica CES, a tertiary health care setting in Medellin, Colombia by analyzing data from 200 randomly selected workers participating in a study of overweight and shift work, between January and July 2014.

Participants (clinical staff, administrative workers and technical and cleaning services) who had worked at the clinic for over one year were invited through an e-mail to be part in the shift and overweight study which included a stress symptoms instrument. Participants working less than one year in the health care setting were not contacted, with the purpose of trying to avoid the circadian adaptation period.

Twelve of the initial 200 randomly selected employees contacted refused to participate. Those who were excluded were replaced by additional randomly selected workers until all 200 workers were eligible for the study. Background characteristics between participants and those workers who refused to participate did not differ statistically. The final sample consisted primarily of nurses and nursing assistants (44.5%) and administrative staff (22%).

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki’s ethical standards; subjects gave their informed consent to participate in the study.

Approval for this study was obtained from CES University Ethics Committee.

Measurements

Demographic, occupational and life style characteristics were assessed through a self-administered questionnaire.

Participants were considered to work in shifts according to their affirmative response to the question: "Do you currently work in shifts?" Then they provided information on shift work duration. Shift work duration and daily working hours of each participant was validated through administrative records.

To provide continuous work for 24 hours, a 12-hour shift system is common in Colombian health care institutions; daytime (7:00 a.m. to 7:00 p.m.) and night time (7:00 p.m. to 7:00 a.m.) followed by either 36 or 60 hours off.

Work-related stress was assessed through a 31-item questionnaire designed and validated for Colombian workers by Ministerio de la Protección Social (Ministerio de la Protección Social, 2010) to detect symptoms indicating stress reactions, Cronbach α=0.889 (p=0.001). The domains are based on the following subjects: physiological symptoms (8 questions), social behavior symptoms (4 questions), intellectual and occupational symptoms (10 questions), psycho-emotional symptoms (3 questions), the response to questions include a four-level Likert scale (always, almost always, sometimes, never), higher levels reflect more/more frequent stress symptoms. To calculate the overall score, in the questionnaire, the average score of items from 1 to 8 is then multiplied by four (4), average score of items from 9 to 12 are multiplied by three (3), from 13 to 22 are multiplied by two (2) and for items from 23 to 31 the average is obtained. Scores below 12.6 reflect low stress symptoms, according to questionnaire designers.

Smoking status was categorized as never smoking, past smoker and current smoker; participants consuming at least one cigarette per day were categorized as current smokers.

Participants consuming liquor from 3-5 times in a month were considered regular drinkers, according to Ha et al. (Ha & Park, 2005).

Regular exercise was considered if participants performed vigorous or moderate physical activity at least once a week.

Authors decided to categorize shift work duration according to the median of the distribution - at ≤ 4 years and > 4 years.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics of participants are summarized according to the type of shift; continuous variables are presented according to the distribution as mean ± standard deviations or medians ± interquartile range, and categorical variables as percentages. Chi- squared test was used to calculate the Odds Ratio with 95% confidence intervals. To test the continuous data between groups, a t-test was used.

Values of p < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. All data were analyzed using SPSS Statistics 21 (SPSS Inc., IBM Corp., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

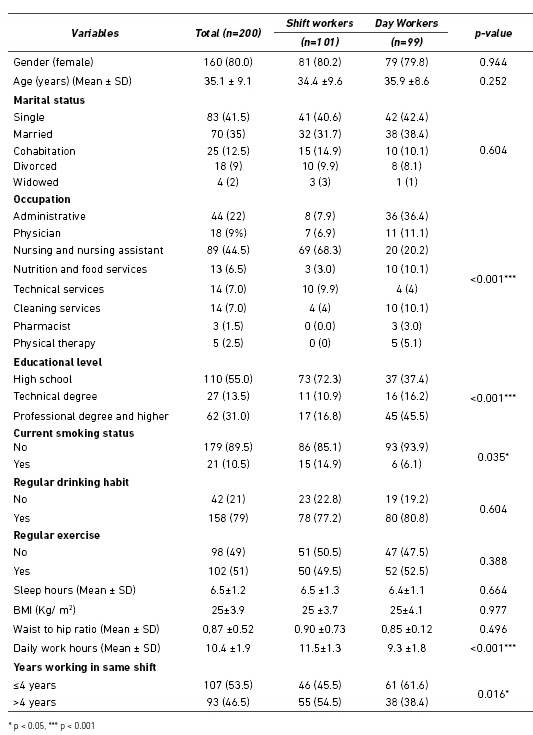

Background characteristics of rotating shift workers and day workers are presented in table 1.

The study sample consisted of 80% female and 20% male participants. A total of 50.5 % of participants performed their work activities in rotating shifts and 49.5% during the day. Most professionals were nurses and administrative staff, differences in occupation are statistically significant (p<0.001) between shift workers and day workers. The mean age of participants was 35.1 ± 9.1 years, most of them were single.

Prevalence of smoking was higher for workers in rotating shifts, 14.9% compared to 10.5% for day workers. This difference is statistically significant.

More than half of participants were regular drinkers, with no statistically significant differences between current shift workers and day workers.

Current shift did not differ from day workers regarding regular physical activity.

Self-reported sleep hours did not differ between current shift workers and day workers (p=0.664)

Educational level was significant higher in day workers, compared to shift workers. (p<0.001).

On average, current shift workers had higher daily working hours than non-shift workers (p<0.01), and higher shift work duration (p=0.01).

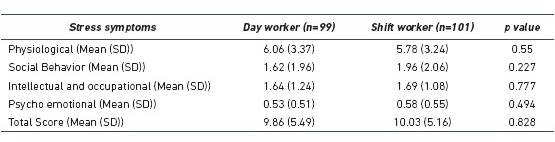

The results for the relation between work-related stress and job schedule type are shown in table 2.

No significant differences were seen in physiological, social behavior, intellectual and occupational and psycho emotional or total symptom scores in shift workers compared to day workers.

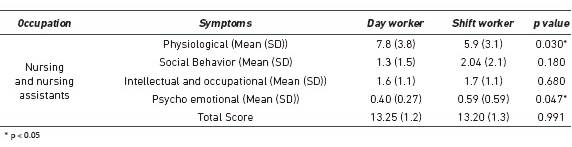

Among occupations, statistically significant differences were observed in physiological and psycho emotional symptoms means in the group conformed by nurses and nursing assistants. (p=0.030 and p=0.047 respectively). Table 3.

Nursing and nursing assistants according to shift did not differ in their background characteristics, except for the educational level (p=0.001) and daily work hours (p=0.001). Yet, shift workers within this group show lower physiological and higher psycho emotional stress symptoms.

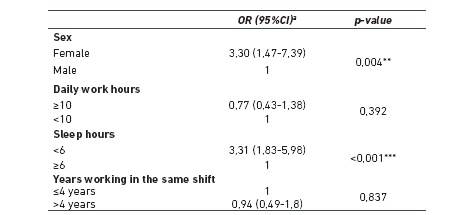

In the overall sample, table 4 summarizes the relationships between overall stress and sex, daily work hours, years working in the same shift and sleep hours after adjustment for age, an increased OR was observed for females and participants reporting less than 6 hours of sleep (p<0.004).

Table 4 Relationship between overall stress and job related factors adjusted by age

a Stress was dicotomized into low vs. high using a cut off point for overall stress of 12.6

** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

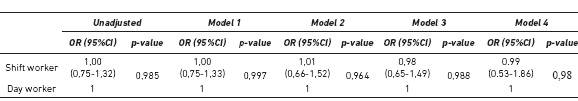

The results of multivariate logistic regression analysis for overall high vs. low stress according to the type of shift for the overall sample are presented in table 5. The unadjusted odds ratio (OR) for stress was 1.00 (0.75-1.32), with no significant association found. Sex-adjusted OR for stress was 1.00 (0.75-1.33), model 2 (adjusted by sex, age, sleep hours and daily working hours), model 3 (adjusted by sex, age, sleep hours, daily working hours and years working in the same shift) and model 4 (4 adjusted by sex, age, sleep hours, daily working hours, years working in the same shift, educational level and smoking) show the same trend, with no significant associations (p>0.05).

Table 5 Multivariate adjusted OR for shift workers/day workers

Model 1 adjusted by sex

Model 2 adjusted by sex, age, sleep hours and daily working hours

Model 3 adjusted by sex, age, sleep hours, daily working hours and years working in the same shift

Model 4 adjusted by sex, age, sleep hours, daily working hours, years working in the same shift, educational level and smoking

Discussion

The aim of this study was to assess the relation between shift work and work-related stress, detecting symptoms indicating stress reactions in a tertiary clinical setting, in Medellin, Colombia. Some of the previously published studies assessing work-related stress and shift work reported a positive relation between them, while some others have failed to detect such association.

Consistently with the results of a study (Knutsson & Nilsson, 1997), which evaluated job strain in shift and day time workers according to Karasek’s Demands/control model, shiftwork was not significantly associated with job strain in the regression model. Also Skipper, et al., evaluating the effects of shiftwork on physical health and mental depression in nurses, found that there was no significant correlation between them (Skipper, Jung, & Coffey, 1990).

Among occupations, it was found in a study that rotating nurses experienced greater job-related stress, when compared with day nurses (Coffey, Skipper, & Jung, 1988). In our study, although the relationship was not statistically significant in the overall sample, when the sample was limited to nurses and nursing assistants, shift nurses and nursing assistants reported significantly more psycho-emotional stress symptoms compared to day nurses and assistants, but significantly less physiological stress. Lin et al. also reported an increased occupational stress in nurses working in rotating shifts compared with those who worked day shift, as measure by having experienced effort/reward imbalance (Lin et al., 2015).

In contrast with our results, using self-reported and objective physiological symptoms, Yuan et al found that nurses who worked in shifts experienced more fatigue symptoms that nurses who work during the day, the acute fatigue symptoms included: "drowsiness and lack of energy", "difficulty concentrating" and "feel uncomfortable" (Yuan et al., 2011).

Analyzing the effect of shift work on job related stress and job performance, a study described that nurses working in rotating shifts seems to experience the most job-related stress, mostly in interpersonal conflicts and management of the unit subscales, similar to the results of our study, where psych emotional symptoms were statistically higher for rotating nurses. This is possibly due to that nurses working in shifts must interact with a different group of people on each shift (coworkers and patients), making it more difficult to create good relationships which might alleviate some of the psycho emotional effects of stress (Coffey et al., 1988).

Interestingly, Coffey et al. also reported that nurses working during the night have less stress in terms of physical working conditions, explained by the fact that demands on healthcare during the night are less stressful than those of the other shifts (Coffey et al., 1988). With this finding in mind, authors of the present study could hypothesize that the number of consecutive nights in each shift may exert an effect over physical symptoms of stress, and further research is warranted.

A number of studies have looked into the association between sleep quality and quantity and shift work, and some of them have found altered patterns in shift workers (Doi, 2005), while in this study there was no a significant difference in the self-reported hours of sleep between shift workers and day workers. When hours of sleep and other factors were controlled for in the multivariate model, the relationship between shift work and overall stress is not significant. However, in our study, overall stress was independently associated with sleep hours and this is an important topic to explore in future studies.

Also in agreement with our results, Tajvar et al reported that there were no significant differences in mental and social symptoms in nurses working in rotating shifts compared to nurses working on permanent day shifts in a medical intensive care unit (Tajvar et al., 2015).

Regarding current smoking status, a significant difference was observed between shift workers and day workers (p=0.035); the number of current smokers in shift workers was more than twice of that found for day workers, showing a similar pattern as in the study performed in a prospective cohort in Japanese male workers (Fujino et al., 2006) and in a study assessing cardiovascular risk among employees from a public university in Brazil (Pimenta, Kac, Souza, Ferreira, & Silqueira, 2012). Also shift workers showed a higher prevalence of current smoking than daytime workers (58.8% vs. 47.6%, respectively) in a study conducted by Kubo et al. (Kubo et al., 2011).

Self-reported shift work history was commonly used in previous studies trying to assess its effect on physical and psychological outcomes. One strength of the present study is that self-reported shift work history was validated through administrative work history data to avoid recall biases.

However, this study has some limitations that need to be considered. First, the sample size is relatively small and our data were collected from self-reported questionnaires and are susceptible to random misclassification by participants, therefore the stress symptoms could be under or overestimated.

Most of the previous studies on shift work have been made in factories, where tasks on each of the shifts are very similar. Similarity of tasks is difficult to assess in healthcare workers, due to fact that there are likely different job requirements for day workers and shift workers, and those requirements can exert a modulating effect on the relationship between shift work and work-related stress.

The cross-sectional nature of this study impedes to prove any chronobiological effect of shift work.

Heavy workload, measured as the number of days of overtime per week can be an independent covariate being associated with job related stress that was not explored in the present study.

Future studies should investigate job demands and control among health care workers, additionally shift work exposure must be explored in depth, including measures such as speed, direction and frequency of night shifts to be further examined. Coping strategies and their relationship with shift work experience is another topic to be further explored.

Conclusion

This cross-sectional study did not show a difference in job-related stress between day workers and shift workers. However, in nurses and nursing assistants specifically, those engaging in shift work reported higher psycho emotional and lower physiological stress symptoms. Negative effects of shift work appear to depend on the type of stress being measured and are not always observed, at least for occupations where the job demands vary shift to shift. More research should be done in order to investigate the influence of some important confounders, such as sleep quality, different job demands between shifts, worker´s control over their jobs and previous experience working in shifts.