Introduction

Advances in the study of emotional disorders (including symptoms of anxiety and depression) have suggested taking a perspective based on the comorbidity of common symptoms and processes underlying psychopathologies (Bullis, Boettcher, Sauer-Zavala, & Barlow, 2019). In particular, high co-morbidities have been reported among anxious symptoms with different disorders such as depressive disorders (66.3% present additional diagnosis of major depression, up to four co-morbid disorders: OR = 2.36 IC95% = 0.66 - 5.66) (Rosellini et al., 2018), leading to questions about the validity of intervention protocols based solely on symptoms (Brown & Barlow, 2009).

As a response to the above, the dimensional models, based on indicators of concomitant biological and psychological vulnerability, emerge as part of a new perspective that may favor the development of more precise nosologies (Brown & Barlow, 2009; Brown, Chorpita, & Barlow, 1998), and new transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioral intervention protocols for different mental pathologies, based on the underlying mechanisms, shared in different pathologies (Rector, Man, & Lerman, 2014), even for previous comorbid psychopathologies (Norton et al., 2013).

Following a dimensional perspective of the processes and factors underlying the different disorders, the transdiagnostic model (TM) “comprises understanding mental disorders based on a range of etiopathogenic cognitive and behavioral processes that cause and/or maintain most mental disorders or groups comprising mental disorders” (Sandín, Chorot, & Valiente, 2012, p. 187). One of the key features of TM is to consider the processes involved in the different emotional disorders (Belloch, 2012), from which several scientific studies were developed surrounding the role of these processes or common factors called transdiagnostic, such as positive (PA) and negative (NA) affect, intolerance of uncertainty and anxiety sensitivity, among others (e.g. Talkovsky & Norton, 2018; Zvolensky et al., 2018).

Affect (positive and negative) has been considered a key transdiagnostic variable in the development of explanatory, evaluative, and therapeutic models of anxiety and depression disorders, including others such as eating disorders (Clark, & Watson, 1991; Clark, Watson, & Reynolds, 1995; Culbert et al., 2016). It is also key for the understanding of the mediator mechanisms of comorbidities in emotional and affective disorders, given its relationship with other variables of interest such as anxiety sensitivity and intolerance of uncertainty (Paulus, Talkovsky, Heggeness, & Norton, 2015).

Watson and Clark (1984) propose a continuation of affect in a positive and negative pole. Negative affect (NA) has been significantly associated with self-reported measures of health deterioration (Watson, 1988), worry and anxiety (Watson, Clark & Carey, 1988). Watson y Clark (1984) define it as temperamental sensitivity to negative stimuli such as fear, anxiety, sadness, guilt, hostility, dissatisfaction, hopelessness, somatic complaints, and a negative view of oneself; while positive affect (PA), correlates with social engagement and is characterized by responses such as enthusiasm, activity, alertness, energy, and rewarding participation. This bipolarity has generated controversy about the independence of these two aspects of affect, although studies of emotion from basic and clinical psychology show that these are two independent factors (positive and negative emotions), the contributions from psychometry support a one-dimensional model of affect in two extreme poles (Padrós-Blázquez, Soriano-Mas, & Navarro-Contreras, 2012) that adjust with greater precision to the understanding of affect at a transdiagnostic level since its beginnings (Feldman-Barrett & Russell, 1998).

The transdiagnostic variable Anxiety Sensitivity (AS), has become a risk factor for panic disorder (Barlow, 2002), which is also useful in the study of other psychopathologies such as anxiety disorders and depression (Sandín, Chorot, & Valiente, 2012). AS is defined as the fear of feelings related to anxiety (Taylor et al., 2007) and comprises three dimensions: somatic, social and cognitive, which are all correlated with measures of the situation and trait of fear, anxiety and behavioral avoidance (Kemper, Lutz, Bähr, Rüddel, & Hock, 2012).

In turn, Intolerance to Uncertainty (IU), defined as a cognitive bias by which a person negatively perceives situations in which he or she is uncertain, has been recognized as a vulnerability variable because of the excessive and uncontrollable concern resulting from a set of negative beliefs about uncertainty and its implications (Koerner & Dugas, 2008). There is evidence that people with high IU often perceive future events as very threatening and unacceptable and need to reduce their likelihood of occurrence through behaviors such as excessive check-ups, seeking assurances, and hypervigilance (Mahoney & McEvoy, 2012). IU has been associated with variations in the heart rate in patients with anxious psychopathologies (e.g. Chalmers, Heathers, Abbott, Kemp, & Quintana, 2016); and it has also been observed that, by therapeutically modifying the IU, the sign of concern in generalized anxiety disorders can be reduced by up to 59%, making it a key variable in the treatment of different emotional disorders (e.g. Bomyea et al., 2015).

Several studies have shown that a person with high NA may also have high IU and AS, a key aspect in the understanding of the clinical history of anxiety and depression disorders (e.g. Mahoney & McEvoy, 2012; Talkovsky & Norton, 2016). According to Carleton, Fetzner, Hackl and McEvoy (2013), the close relationships between AS and IU in avoidance behaviors, as complementary transdiagnostic variables, would facilitate the understanding of panic disorders; however, they point to the need of further research. In turn, in a study of patients diagnosed with panic disorder with and without agoraphobia, Shihata et al. (2016) found that the AS variable presented greater variance explained in panic symptoms, and the AS probably measured the IU; however, the authors recommended analyzing the role of the IU in panic symptoms independently of the AS in a much broader model.

Reports presenting empirical evidence of those variables with greater predictive capacity (e.g. Brown & Barlow, 2009) should support an TM for emotional problems. In this regard, close associations have been found between variables such as NA and PA in addition to a high predictive capacity, the subsequent development of cognitive and emotional responses present in the IU and AS, all of which predict anxious and depressive symptoms. A hypothetical transdiagnostic model that includes these associations between transdiagnostic variables and emotional problems would allow integrating recent findings on the interaction between these variables (IU, AS, NA, and PA), given that currently there is no unifying correlational proposal to advance the explanations of the comorbidities of emotional disorders. The objective of the study, therefore, was to develop a structural model that includes the IU, AS, NA, and PA variables in emotional problems such as anxiety and depression.

Method

Type of research

A quantitative investigation was carried out with an explanatory transversal design, following the proposal of Ato, López and Benavente (2013); it is a design with manifest variables (DVM), in which a structural network of relations between variables represented in a regression equation system was defined, using a covariance matrix and a path analysis, resulting in a model whose adjustment was evaluated through structural equation indicators.

Participants

An intentional non-probability sample of 486 participants was formed who met the following inclusion criteria: a) be of legal age (18 years), b) have no psychotic or bipolar psychopathology, c) have no auto- or heteroagressive behaviors, and d) not be receiving psychopharmacological treatment. Participants had an average age of 27.16 years (DE = 5.38, minimum = 20, maximum = 40), 50.2% women (n = 244) and 49.8% men (n = 242). The scores obtained on the scales of the study showed no statistically significant differences between male and female sexes (p > .05) for all transdiagnostic variables (p = .200 and p = .900).

Instruments

Positive and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS). The self-applied scale developed by Clark and Watson (1991) to test the dimensions of the tripartite model of anxiety and depression (low positive affect, high negative affect, and arousal anxiety). The instrument translated into Spanish used for this study contains 20 items (10 for negative affect and 10 for positive) (Robles & Páez, 2003). Reagents describe different emotions and feelings that a person may experience, they are scored on a Likert scale of five points (1 very little or nothing, up to 5 extremely). PANAS psychometric indicators report a high internal consistency for both positive affect: Cronbach’s alpha between α = .85 and .90, as for the negative affect: α = .81 and .85, showing favorable correlations with Beck’s Anxiety (BAI) and Depression (BDI-II) Inventories (r = .32 and .55). The Cronbach alpha coefficient obtained in this study was .89 for positive affect, and .84 for negative affect.

Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3 (ASI-3). Elaborated by Taylor et al. (2007) to test fear and anxiety reactions to the experience of physical symptoms, cognitive lack of control and socially observable symptoms, grouped into three scales: physical, cognitive and social. This study used the 18-item version proposed by Sandín, Valiente, Chorot, and Santed (2007), with a five-point Likert response format ranging from Nothing or Almost Nothing (0) to Very Much (4). It has a high internal consistency (α = .91 in the total, and ranges between .83 and .87 for subscales), with a model confirmed by Sandín et al. (2007) of three factors plus one hierarchically superior. Also, ASI-3 presented a significant correlation with the negative affect scale of PANAS (r = .43). In this study, the Cronbach alpha coefficient obtained for ASI-3 was .90.

Intolerance Uncertainty Scale (IUS). Developed by Freeston et al. (1994) to assess the reasons people care and do not tolerate uncertainty. For this study, the IUS adapted for Spain by González, Cubas, Rovella and Darías (2006) was used. It has 27 items that are scored on a Likert scale of five points ranging from 1 (nothing characteristic of me) to 5 (extremely characteristic of me). The Scale comprises two main factors: uncertainty leading to inhibition (α = .93) and uncertainty leading to uncertainty and inhibition (α = .89). Cronbach’s alpha for full scale is .91, and test-retest reliability is r = .78. In this study, the Cronbach alpha coefficient obtained for the UIS was .95.

Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI). Designed by Beck, Epstein, Brown and Steer (1988) to test the presence and intensity of physiological and cognitive anxiety symptoms, with a total of 21 items that should be evaluated from 0 to 3 according to the symptoms experienced by the person during the last week. The Spanish version prepared by Sanz, García-Vera and Fortun (2012) presented a Cronbach alpha of .90 for Spanish samples, an average score of 25.7 (SD = 11.4) for patients with anxiety and an average of 15.8 (SD = 11.8) for patients without anxiety. In this study, the Cronbach alpha coefficient obtained for the BAI was .92.

Beck Depression Inventory, second edition, Spanish version (BDI-II). Developed by Beck, Steer and Brown (1996) to measure the severity of depressive symptoms according to the DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, APA, 1994). For this study, we used the BDI-II adapted to the Spanish language by Brenlla and Rodriguez (2006), consisting of 21 items that are scored according to the severity of the symptom during the last week. This instrument has shown a high internal consistency (α = .94 and α = .88 in a previous diagnosis of major depression) and favorable predictive validity. In this study, the Cronbach alpha coefficient obtained for the BDI-II was .90.

Procedure

We invited participants to the study through an open and voluntary call, and we subjected those who expressed an interest to a compliance verification of the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Subsequently, the general objective of the research was explained to them, they were informed that all concerns related to the results could be requested via email to the main author of the research and they were asked to sign the corresponding informed consent containing the ethical considerations of the study which had been previously approved by the central research committee of the University that sponsored the study (Project 4110016). The participants then completed the set consisting of the five instruments in approximately 20 minutes.

Data Analytic Plan

We carried out the analysis using the SPSS 25 software. First, we examined measures of central tendency as mean and standard deviation, and of dispersion as range, asymmetry and kurtosis in all transdiagnostic and symptomatic variables. The normal distribution, absence of multicollinearity, and homoscedasticity among the variables were verified. Subsequently, Pearson’s product-moment correlations were performed to identify the relationships to be used in a path analysis using the AMOS 23 software, in which structural equations were used to verify the fit of the proposed model composed of indicator variables represented in a rectangle (NA, PA, IU, AS, anxious symptoms, and depressive symptoms), and the latent variables in ovals (affective and emotional symptoms). The trail diagram examined whether the hypothetical relationship patterns were consistent with the observed covariance matrix. The adjustment indexes used were those recommended by Hu and Bentler (1988) for varied samples with different distributions, were Chi-Square (χ2, cut-off point p > .05), Good Fit Index (GFI > 0.90), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI > 0.95), Comparative Fit Index (CFI > 0.95) and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA < 0.06). Revisions of modification indexes and significant regression coefficients were conducted to determine the best adjusted empirical model.

Results

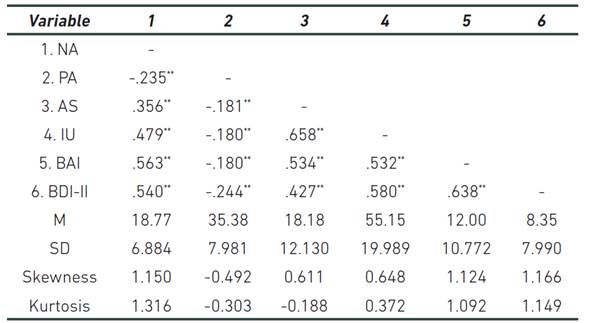

Table 1 shows Pearson’s mean scores, standard deviations, and dispersion measures, as well as correlation coefficients r. Scalar values were distributed normalized according to skewness (expected between -3 and 3) and kurtosis (expected less than 6) (Kim, 2013). Outliers were detected using the Mahalanobis distance test with a p criterion less than .001 (Brereton, 2015), and it was found that we should remove a participant from the total sample. It also resulted that the variables did not show multicollinearity (r p > .90), both transdiagnostic and symptomatic, which allowed to carry out the subsequent analysis of trails.

Significant positive correlations (p < .05) were found between negative affect with anxiety sensitivity (r = .356), and intolerance to uncertainty (r = .479), and negative correlations between positive affect and the transdiagnostic variables AS and IU, although smaller respectively (r = -.181 and -.181), in the same way, between negative affect and the symptomatic variables of anxiety (r = .563) and depression (r = .540). It also highlights significant negative correlations of positive affect with symptomatic variables of anxiety and depression, especially with depression (r = -.244) as opposed to anxiety (r = -.180). Table 1 shows the correlations obtained with all the other variables of the study.

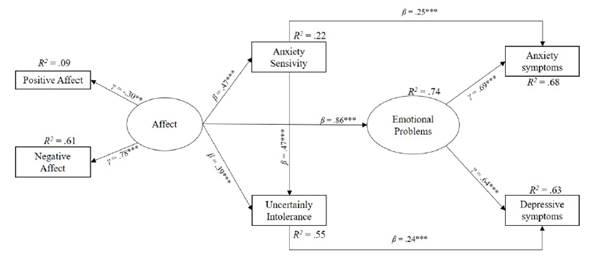

Based on these results, a structural model was proposed in which the predictors derived from the correlational analysis between the transdiagnostic variables and the symptomatic variables were diagrammed. Figure 1 shows the model obtained accor-ding to structural adjustment indicators. The path diagram was proposed taking into account the theoretical implications on the predictive capacity of each variable in emotional problems as a latent variable, and the independence between indicators, whether predictors or criteria. The result was a final transdiagnostic model with favorable indexes for predicting emotional problems (χ² = 7.449, gl = 5, p. = .189, GFI = .995, CFI = .998, TLI = .993, and RMSEA = .032).

Table 1 Descriptive and Pearson’s moment product correlations between transdiagnostic and symptomatic variables (n = 486)

Note: NA (Negative Affect), PA (Positive Affect), AS (Anxiety Sensitivity), IU (Intolerance of Uncertainty), BAI (Anxiety), BDI-II (Depression), M (Mean), SD (Standard Deviation). ** p > .01 (bilateral)

The resulting model shown in Figure 1 explains 74% of the variance for emotional problems (R2 = .74), and particularly for anxiety symptoms (R2 = .68) and depression symptoms (R2 = .63). It is highlighted that negative affect (NA) is the variable that provides the greatest variance explained to the measure of affect (R2 = .61, γ = .78, p < .001) as opposed to positive affect (PA) (R2 = .09, γ = -.30, p < .01), a measure that predicts emotional problems (β = .86, p < .01), and to a lesser extent the variables AS (β = .47, p < .01) and IU (β = .39, p < .01), also statistically significant with less predictive capacity.

Discussion

The objective of this research was to develop a structural model that includes positive and negative affect, anxiety sensitivity and intolerance to uncertainty variables in emotional problems such as anxiety and depression. The high variance explained, as well as the significant correlations between predictors and symptoms in an adjusted structural model, are findings that constitute new evidence on the possible causal relationship between the transdiagnostic variables (Affect, AS, IU), and the symptoms of anxiety and depression as emotional problems. The model obtained is empirically adjusted and validates the correlational transdiagnostic hypotheses that led to its approach.

These findings offer a series of relevant clinical implications, since they allow strengthening the procedures at a psychotherapeutic level in terms of sequentiality of techniques and structuring of the sessions. For example, in the therapy of cases of disorders with elevated emotional symptoms, the model obtained suggests intervening the characteristic responses of negative affect (NA), increasing those of positive affect (PA), and modulating their functional emotional cognitive response (IU and AS), through strategies of emotional regulation and reduction of avoiding patterns. Such strategies may increase the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions by simultaneously significantly reducing the intensity of emotional and affective symptoms (Brown & Barlow, 2009).

It has been reported that these alternatives and intervention strategies mentioned are promising for the reduction of depression symptoms, although not to the same extent for anxiety symptoms (Wirtz, Radkovsky, Ebert, & Berking, 2014), an aspect that differs from the results of this study, given the minimal differences in the predictive capacity of the model with a greater variance for anxiety than for depression.

In this study, significant associations of affect with the IU and minor with the AS were obtained, which suggests that affect would be associated with the development of depressive symptoms, particularly when the PA is low, although it has not been clearly documented if it has moderating effects, nor if it clearly predicts anxiety symptoms (Riskind, Kleiman, & Schafer, 2013); while, on the contrary, the NA does predict the increase of anxiety symptoms. In this way, Thibodeau, Carleton, Collimore and Asmundson (2013) reported an explained variance of 42% of PA and NA in anxiety symptoms; however, the causal role of affect in its two dimensions is not yet clear in anxiety and depression symptoms (Cohen et al, 2017); and Harding (2016) pointed out that the affect variable from its high NA and low PA dimensions is associated with catastrophic and ruminative cognitions, which together would have a modulating role in the depressive response.

The affective dimension proposed in this study in a latent variable composed by NA and PA, corresponds to two factors of the tripartite model of anxiety and depression, used to explain the shared variance between anxiety disorders and mood in a single symptomatic dimension of pleasure-displeasure (Brown, Chorpita, & Barlow, 1998), related to the concepts of neuroticism and extraversion (Sandín et al., 2012). Therefore, emotional problems are presented in a single negative and positive affective dimension; for example, a person may present symptoms of social anxiety (high negative affect) and moderate comorbid depressive symptoms (low simultaneous positive affect) (Dunkley et al., 2017); it is then a measure of general affect that reflects the intensity of the emotional and affective response (Rubin, Hoyle, & Leary, 2012). In this study, the NA showed the greater explanatory capacity of the latent variable (affect), as opposed to PA; findings consistent with other reports (e.g. Bullis et al., 2019; Hofmann, Sawyer, Fang, & Asnaani, 2012; Watson & Clark, 1992).

According to the results obtained, the AS variable becomes a key variable to be taken into account in a transdiagnostic model of emotional problems. AS has been considered as a higher-order variable that would explain not only the physical sensations associated with anxiety, but also other responses such as experiential avoidance (Allan et al., 2014); in this same line, a structure composed of a higher-order general factor has been reported (Ebesutani, Mcleish, Luberto, Young, & Maack, 2014), although other similar studies have disputed this structure (e.g. Chavarria et al., 2014; 2015; Rifkin, Beard, Hsu, Garner, & Björgvinsson, 2015), in contrast to the model of three factors that make up the construct of the AS from its inception: social, physical and cognitive sensitivity (Kemper et al., 2012).

In this study, AS predicts the onset of anxiety and depression symptoms, although it better predicts anxiety symptoms. Both IU and AS are key transdiagnostic dimensions in anxiety and depression problems, which highlights the cognitive vulnerability shared between the different disorders and in turn, underpins the current explanatory and therapeutic models of cognitive-behavioral cutting (Brown, Meiser-Stedman, Woods, & Lester, 2016). As already stated by McEvoy and Mahoney (2012) regarding the understanding of pathologies such as generalized anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, partially for social phobia, panic disorder, agoraphobia, and major depression. It seems that the IU represents a component of vulnerability for the development of highly significant emotional disorders, given the excessive and uncontrollable concern and the subsequent appearance of anxious and depressive symptoms, often with high comorbidity (Carleton, 2012; Carleton et al., 2013). It has become necessary to know more precisely the associations between NA, PA and the moderating role that the IU and AS variables may have in the prediction of emotional and affective symptoms.

This study has some limitations. First, it is recognized that the use of a cross-sectional design limits the possibilities of estimating the causality between the transdiagnostic variables and the symptoms evaluated, which could be more appropriately evaluated in a longitudinal study. In this sense, it is suggested to develop further prospective studies in which variables such as the IU, AS, PA and NA are evaluated in asymptomatic populations. Second, the use of a non-discriminatory sample by previously diagnosed symptomatic groups limits the explanatory considerations of the model resulting from the study. The use of clinical samples in future studies would help corroborate the findings obtained in the research.

In conclusion, a preliminary transdiagnostic model was obtained based on the NA variable with a significant predictive value, a PA with less explanatory capacity, which constitutes an affective variable with a high association with the AS variables predictor of anxious symptoms, and the IU predictor of depressive symptoms, both being transdiagnostic variables capable of explaining in a 74% the variance of emotional and affective problems.

Despite the above limitations, it is deemed essential to have an explanatory and therapeutic model that includes the NA, PA, IU and AS variables in protocols that particularly highlight NA as a factor of high interest for the development of subsequent transdiagnostic interventions (Rector et al., 2014) and the need to continue investigating causal mechanisms and co-variations between transdiagnostic and symptomatic variables in order to understand the diagnostics comorbidities is recognized. These findings guide future lines of research on the maintenance variables of problems related to depression and anxiety, which would allow progress in the development of cognitive-behavioral intervention protocols (Gros, Allan, & Szafranski, 2016), much more precise and adjusted to different disorders and population samples.