Introduction

The negative side of organizational politics embedded in many organizations may impede employees' performance because it requires strenuous and exhausting workloads, especially when unfair practices in the work environment are present and may consume their physical and psychological well-being. As a result, employees may express pessimistic attitudes, affecting their work behaviors and producing other adverse consequences to their psychological well-being (Bedi & Schat, 2013). (Wangui and Muathe. 2014) argue that there are several work scenarios in many types of organizations. For example, there are different kinds of alliances and group dynamics, and one group may incite dirty work politics such as aggression towards other co-workers, or they may disobey the rules of the organization's protocol, or they may use gossip to slander a co-worker's reputation and even sabotage the line of production. All these behaviors can have unfavorable consequences on the organization's work culture and especially the organization's core values and objectives. Furthermore, when an organization has limited resources and resources are not fairly allocated, employees compete over those resources, mainly over a job position with authority and power. Consequently, arguments, conflicts, and other unethical behaviors may occur because employees compete over promotions, a salary raise, and even an office space.

Subsequently, these types of behavior may impact the workflow and productivity of the organization's goals and objectives. According to (Buchanan and Badham. 2008), since the 1990s, a great interest grew to study politics in organizations. Many employees expressed negative perceptions of organizational politics and the aftermath it has on many organizations. Also, (Al-Abbrow. 2018) states that organizational politics has gained an interest in research examining the influential factors and behaviors in which organizations operate over the past few years.

As a result of previous research on politics in the workplace, the authors Kacmar, Ferris, and Carlson in the late 1990's came up with an instrument to measure perceptions of organizational politics, the 15-item Perceptions of Organizational Politics Scale (POPS; Kacmar & Carlson; 1997) is a well-known and widely used instrument applied in numerous studies throughout the years (Valle et al.; 2019; Atinc et al., 2010). (Kacmar and Carlson. 1997) argue that the 15-item POPS Scale English version is proven to measure organizational politics' perceptions in the workplace in various organizations where employees perceive dirty office politics. For example, they believe there are unfair policies, a sense of injustice, and unethical work behaviors such as nepotism.

On the other hand, this study aims to evaluate the adapted and translated version as well as to access the psychometric properties of the 15-item Puerto Rican Perception of Organizational Politics Scale (POPS) Spanish version with a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) and Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to test the construct validity and reliability. First, the researcher must make sure the instrument measures what it is supposed to measure. Also, further, test the new instrument with robust statistical analyses to improve reliability and validity and provide consistent results. Applying a Confirmatory Factor Analysis with Structural Equation Modeling is a robust statistic that may improve the Puerto Rican POPS scale's reliability and validity after any adjustments and test the construct validity.

Further, another aim in this study is to examine other psychometric properties using Cronbach's alpha formula and the McDonald's Omega and the Composite reliability (C.R.) for reliability and the average variance extracted (AVE) and along with the composite reliability (C.R.) for the convergent and discriminant validity analysis with the square root or MSV. Besides, analyze the factorial structure of the 15-item Puerto Rican POPS Scale Spanish version. Moreover, this study pretends to answer the following questions: Will the Puerto Rican Spanish adapted version of the POPS Scale reproduce the exact structure of the original English version scale with optimal reliability and validity values? Furthermore, how are the perceptions of the organizational politics obtained in this study with the participants?

In sum, this study may allow the Puerto Rican POPS Scale Spanish version to have better psychometric properties and contribute to new studies on organizational politics and focus on Puerto Rico's organizational behavior. There are no valid instruments in Puerto Rico that measure the perception of organizational politics in the workplace. Having a reliable instrument that measures perceptions of organizational politics in Puerto Rican organizations is fundamental in advancing research and developing new theoretical grounds in Puerto Rico. Also, testing the Puerto Rican POPS scale Spanish version can be applied in future research, primarily focusing on organizational politics.

Definition of Organizational Politics

According to the literature review, there are various definitions of organizational politics, but these are the well-known classical definitions; according to (Valle and Perrewe. 2000) state that it is "The exercise of tactical influence which is a strategic goal-directed, rational, conscious and intended to promote self-interest, either at the expense of or in support of others' interests" (p. 361). Also, (Vigoda-Gadot. 2003) argues that it is the "Intra-organizational influence tactics used by organization members to promote self-interests or organizational goals in different ways" (p. 31). (Ferris et al. 2005) point out that it is the "Ability to understand effectively others at work, and to use such knowledge to influence others to act in ways that enhance one's personal and or organizational objectives" (p. 127). However, for (Allen et al. 1979), it is "The acts of influence to enhance or protect the self-interest of individuals or groups" (p. 77). The definition of organizational politics in the 15-item POPS Scale English version by the original authors (Kacmar and Ferris. 1991) argue that organizational politics is an elusive type of power relations in the workplace. It represents a unique domain of interpersonal relations characterized by people's direct or indirect (active or passive) engagement in influence tactics and power struggles. These activities are at securing or maximizing personal interests or avoiding adverse outcomes in the organization.

Theoretical grounds on Organizational Politics

One of the earliest theoretical models proposed by Ferris and Kacmar that may explain the effects of perceptions of organizational politics is centralization. Centralization is where power and control come from upper management. Thus, there is a perception that power control involves political behavior involved during the organization's decision-making process. Also, formalization is when employees must follow a set of rules, standards, and written policies. When there are high levels of formalization, supervisors and managers usually have a status of power and control, and they may increase higher levels of negative perceptions of organizational politics in the workplace (Ferris & Kacmar, 1992).

Moreover, the hierarchical level affects politics' perception, it usually comes from upper management, and the hierarchical levels are distributed among managers and supervisors. Therefore, they believe that the hierarchical level should exist inside the organizations. However, it usually leads to destructive office politics in the place of work when the upper management engages in political work behavior. Lastly, there is a close relationship between the span of control with perceptions of organizational politics. For example, many employees must report to a supervisor, but the supervisor may not have the time and dedication to resolve many employees' concerns. Therefore, it usually leads employees to experience uncertainty and ambiguity in fulfilling their tasks and duties (Atinc et al., 2010; Ferris & Kacmar, 1992).

(Buchanan and Badham. 2008) argue that John (Rawls' theory of justice. 1971) may explain the perception of organizational politics. It is when the organization's resources will not fairly allocate its recourses. Employees may feel that there is a lack of control in the distribution of the resources, and there is a dark triad of work politics involved with inadequate procedures and decision-making policies with other poor business ethics and practices. On the one hand, the structure power embedded in organizations is the mobilization of bias when it favors some members in the organization and not others. On the other hand, the organization's norms and procedures are designed systemically and usually benefit only a few influential members, and a large group of people is usually at a disadvantage.

Another theory that may explain office politics in the workplace is that certain individuals have specific personality traits of Machiavellianism proposed by Cristie and Geis in 1970. According to (Atinc et al. 2010), (Buchanan and Badha. 2008) argue a relationship between increased detrimental dirty office politics and Machiavellianism in which the individual plays and practices political behavior in the workplace. The individual is cynical, self-centered, and willing to do anything to achieve a personal benefit at others' expense. These individuals increase the negative perception of politics in the workplace, and there is a close relationship between Machiavellianism behavior and perceived perceptions of negative politics with political behavior.

A review of POPS

The original (POPS; Kacmar & Ferris; 1991) underwent a two-phase study of 31 items, and at the final stage of the study, the scale ended with 13 items. Afterward, the 13-item POPS Scale underwent a third study by (Kacmar and Carlson. 1997) to further validate the scale. They examined the modified POPS Scale's dimensionality and applied a structural equation modeling to the POPS data variance /covariance matrix with new items. According to the three-factor and the one-factor model, the fifteen items loaded on one factor using LISREL 8 software. The results show that the three-factor model was a better fit. The following results were as follows: The 15-item POPS Scale indices were RMSEA = .07, GFI = .91, AGFI = .87, NFI = .86, NNFI = .87, PNFI = .72, CFI =.91, IFI =.91, and RFI = (.84).

The modification indices of Lambda χ examined the discriminant validity of the factors. It shows that only eight of the 30 values (27%) exceeded the recommended cutoff. The t- values ranged from 3.02 to 17.89, all significant at the p < 0.01 level. It indicates that all the items were significantly related to their construct. The Squared Multiple Correlations (SMCs) ranged from .03 to .75 (mean = .41; median = .34; 6 > = .45). The final version ended with 15 items and has composite reliability of (.87). The Chi-square value was statistically significant (χ2 (87) = 237.29, p = .00), indicating that the model does not fit the data since it is sensitive to large samples. In the final sample, the χ2/df ratio was 2.73, indicating a good model-to-data fit (Kacmar & Carlson, 1997).

The 15-item POPS Scale English version showed consistencies throughout the years, and the scale has a good indicator measuring perceptions of organizational politics in the workplace and possesses a valid construct validity. The scale contains three dimensions. The first is General Political Behavior when the employee gains personal interest and benefits at others' expense. Usually, there are unclear rules concerning how their general work behavior should be inside the organization. The second is the Go along to get ahead, in which a person who wants to maintain themselves away from conflicts usually is neutral. The third dimension is the Pay and Promotion Policies, which refers to the organization's policies, rules, and promotions. However, this may promote political behavior when employees believe in unfair promotions and evaluations, and someone they believe did not deserve the promotion (Kacmar & Carlson, 1997).

Research on POPS

(Rana et al. 2021) studied 780 faculty members of higher education institutions in Pakistan. The authors state that POPS significantly impacts employee outcomes, including employee turnover intention, job satisfaction, employee engagement, and counterproductive work behaviors. Another research by (Khushk et al. 2021) examines the role of job pressure and a relationship between organizational politics and turnover intention among faculty members in the universities in Pakistan. The authors concluded that there is a positive relationship between organizational politics with turnover intention. Also, they argue that management can predict employees' turnover intention with organizational politics, and the mediating variable is stress. Furthermore, they indicate that organizational politics correlates with stress, which the faculty members may want to leave the university, and there are politics involved in the workplace.

In the United States, (Wiltshire et al. 2014) completed an online study at Syracuse University. One of the scales used was the 15-item English version (POPS; Kacmar & Carlson; 1997) to examine Honesty-Humility personality traits on work outcomes. The sample was 66.2 % of the United States of America, 5.6 % from Canada, 4.4% from India, and 3.7% from the United Kingdom. The authors concluded that there are unpleasant workplace outcomes associated with organizational politics in the place of work. Further, that POPS shows a significant work outcome in which workers are likely to act in counterproductive work behavior and use office politics.

In Iraq, (Al-Abbrow. 2018) analyzed organizational politics' effects on organization silence through the mediating role of organizational cynicism in a sample of 346 workers in three public hospitals. Al-Abbrow concluded that there was a relationship between organizational politics and organizational silence. Also, there was a significant relationship between organizational cynicism's mediating role and the relationship between organizational politics and organizational silence.

Lastly, according to research, (Cacciattolo. 2015) points out that detrimental organizational politics may harm job performance, evaluation, and organizational commitment, and it mainly affects employees who cannot express their concerns and have someone to represent them on their behalf. Therefore, it may produce a great deal of stress and work conflict in the workplace. Also, there is a close relationship between unfair office politics and job anxiety in employees having no power status, leading to higher stress levels.

Methodology

This study applied a quantitative approach with psychometric instrumental and cross-sectional research design and non-probabilistic and snowball sampling (Creswell, 2014; Goodman, 1961; Montero & Leon, 2007). In the instrumental research design, measuring the instruments' psychometric properties analyzes and describes a population's behaviors, beliefs, and attitudes. This study also applied a pilot study to test and identify the 15-item Puerto Rican POPS Scale Spanish version in Puerto Rico.

Participants

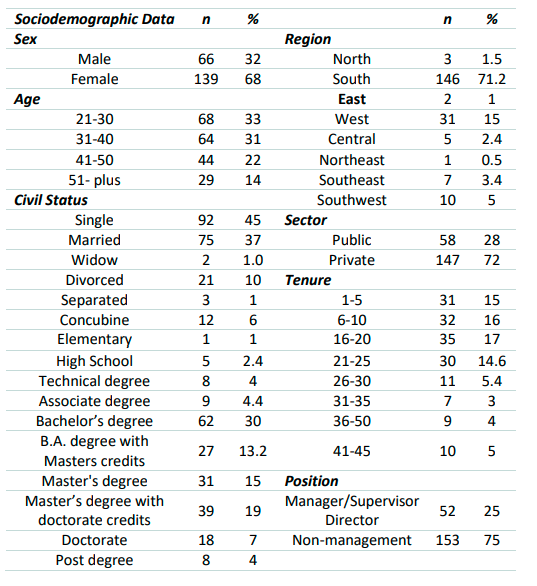

The sample was 205 working adults, 21 years old and older (M= 2.17; SD= 1.04). Also, apply a snowball sampling; many organizations declined to participate in this study. One of the alternatives was to collect the data using this technique. (Goodman. 1961) says that snowball sampling is a random sample of individuals drawn from a given finite population to infer statistical inferences about various aspects of the population's relationships. It serves to identify potential participants based on referrals or word of mouth. The following Table 1 shows the sociodemographic data.

Instruments

The participants received the first instrument was the Sociodemographic Questionnaire. It collected the following datum: geographic work location, civil status, sex, age, sector (private and public), education level, job position, and tenure. Then the participants received the second instrument, the 15-item Puerto Rican Perceptions of Organizational Politics Scale Spanish version, and it is a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. See Appendix A and its translation.

Procedure

First, the Pontifical Catholic University of Puerto Rico and the Institutional Review Board (IRB) granted authorization. The IRB granted the protocol (CEG-18-2016). Next, the researcher contacted the author of the 15-item POPS Scale English version and granted permission. Afterward, two bilingual subject matter experts that reside in Puerto Rico and have a master's degree in languages from the University of Puerto Rico translated the original document from the source language, which in this case, is in English to Spanish. Next, the translation process begins in which the second translator has not seen the original document English version translated by the first translator to Spanish. The second translator's job is to translate the Spanish version scale back to English. Afterward, the translators must repeat steps one and two until the target language is Spanish, acceptable, and equivalent to the English scale's original content. Lastly, the translators must modify the Puerto Rican POPS instrument Spanish version accordingly to (Brislin's recommendations. 1970,1986).

Subsequently, a panel of two subject matter experts from Puerto Rico with a doctoral degree in Clinical Psychology and Industrial-Organizational Psychology who understands English reviewed the 15-item Puerto Rican POPS Scale Spanish version to verify the translation accord with the 15-item POPS English version to determine the semantic and if it fits the Puerto Rican cultural-linguistic. The four subject matter experts were informed about the aim of the study and requested from the two subject matter experts with a doctoral degree in psychology if they had experience in psychometric evaluating instruments. The two subject matter experts with doctoral degrees would also recommend the other two certified expert bilingual translators and vice versa the Puerto Rican POPS Scale Spanish version in the comprehension and response difficulties usually associated with adaptations and translations in instruments and modification. The information was recorded in paper and later on destroyed to protect the subject matter experts' confidentiality. Next, a pilot study of 30 working adults in Puerto Rico over 21 years old using word of mouth and recruited to answer the scale. The participants' instructions are to write comments concerning the questions if they had difficulty understanding each item. Then four subject matter experts made any necessary modifications to the 15-item POPS Scale Spanish version.

Consequently, the study began, and the 205 participants received consent forms, approved by the Pontifical Catholic University of Puerto Rico and its Institutional Review Board (IRB) committee accordingly to APA standards, and the 15-item Puerto Rican POPS Scale Spanish version in paper forms. The participants were informed about the purpose and rights to volunteer and withdraw at any time from the study. Also, when confidentiality and when the results are available. The participants voluntarily participated and used word of mouth in this study.

Statistical Analysis

Then three computer software, the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 24 JASP and the Mplus, was used to analyze and compute the data's statistical analysis in this study. The computer software used to carry out the descriptive statistics, the scale's reliability applying the Cronbach's Alpha coefficient formula, the McDonald's Omega formula, and examine any outliers. (Deng and Chan. 2017) argue that the McDonald's Omega is a reliability coefficient similar to Cronbach's Alpha. However, (Peterson and Kim. 2013) argue that omega has the advantage of considering the strength of association between items on a scale, and it is a better option in Confirmatory Factor Analysis. According to (Deng and Chang, 2017; DeVellis. 2016), an internal consistency reliability of .70 or above is an acceptable threshold. However, .80 and above is considered a good internal consistency reliability.

The first step is to conduct descriptive analyses (means, standard deviations, asymmetry, kurtosis, Shapiro-Wilk) in the Spanish version of the 15-item Puerto Rican POPS Scale. Next, a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) tests the construct validity with structural equation modeling (SEM). Finally, a CFA with an SEM and a Diagonally Weight Least Squares (DWLS) estimation performs validation and data analysis. Choosing the DWLS estimation fits well since the Spanish version of the 15-item Puerto Rican POPS Scale is a Likert-type scale with an ordinal rating.

Next, to test the Chi-Square and determine the model fit. However, Chi-Square is sensitive to sample size and checks whether a model fits in the population. It assesses the overall fit and the discrepancy between the sample and fitted covariance matrices. There are many thresholds based on the literature review to establish the indices. The Comparative Fit Index (CFI) ≥.90 is acceptable, but a CFI ≥ .95 is considered a good value. The Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) ≥ .90 is a fair value, but a TLI ≥ .95 is good. The Incremental Index of Fit (IFI) ≥ .90, Goodness of Fit (GFI) ≥ .90, and the Normed Fit Index (NFI) ≥ .90 are acceptable, but the indices more than .95 are excellent, Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) value less than .08, and Root Mean Square Error Approximation (RMSEA) ≤ .08 is acceptable, but an RMSEA ≤ .05 is considered excellent. In addition, the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) and the Composite Reliability (C.R.) examine further validity concerns factor loadings on each scale's construct (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). The Composite Reliability tests the internal consistency in the scale items, sometimes called the construct reliability. It is equal to the actual score variance relative to the total scale score variance (Brunner & Süb, 2005). The composite reliability (C.R.) indicates the shared variance among the observed variables used to indicate a latent construct (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Next, a bivariate Pearson correlation tests the scale's internal concurrent validity with each Puerto Rican POPS subscales Spanish version.

Results

Item Analysis

According to the four subject matter experts, the first step is to examine the 15-item POPS Spanish Scale version are the semantic and translation. According to the results, all four subject matter experts agreed with all items and their translation. The results of the V-Aiken show a confidence interval of 90%, and all the items scored a value over .80 (Aiken & Groth-Marnart 2005).

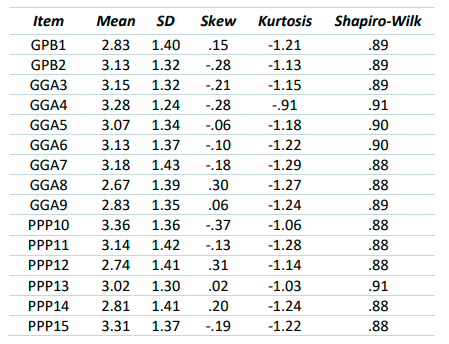

The second step examines any normality violations of the Spanish version's 15-item Puerto Rican POPS Scale. Later, decide if any adjustments in the scale may improve the reliability and validity and further analysis by removing the items that violate the thresholds-also, an analysis of the items using asymmetry and kurtosis indices. The asymmetry analysis showed that 15 items on the scale presented values below (1). Concerning kurtosis, 14 items presented values -1, and only one item presented values (0). The skew and kurtosis values did not exceed the thresholds of ± 2.0 (Hair et al., 2014). The Shapiro-Wilk tests may test in samples below 300 for test normality of distributing the scores for two groups (Field, 2017; Shapiro & Wilk, 1965). In this case, males and females. According to the Shapiro-Wilk test results and a visual inspection of their histograms, normal Q-Q plots and the box plots showed that the scores were approximately normally distributed for males and females. The males had a skewness of .195 (SE = .295) and kurtosis -.412 (SE = .582) and females a skewness of .172 (SE = .206) and kurtosis -.058 (SE = .408). The following Table 2 illustrates the skew, kurtosis, and Shapiro-Wilks.

Also, to test the multivariate normality using SPSS to calculate Mahalanobis distances, the distance of a particular case from the centroid of the remaining cases. It will detect any strange pattern of scores across all nine sociodemographic independent variables with the dependent variable, the Puerto Rican POPS Scale Spanish version. The results show 24.30, the maximum Mahalanobis distance. According to the literature, the critical value for nine variables is 27.88 (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013). In other words, in the sample of this study, there is no violation of multivariate normality.

Table 2 Descriptive Statistics and Items Distributions for the 15-item POPS Scale Spanish version (n = 205).

Note: GPB 1 to GPB 2 is the General Political Behavior dimension; GGA 4 to GGA 9 is the Go Along to Get Ahead dimension; PPP 10 to PPP 15 is the Pay and Promotion Policies dimension, S.D. = Standard Deviation

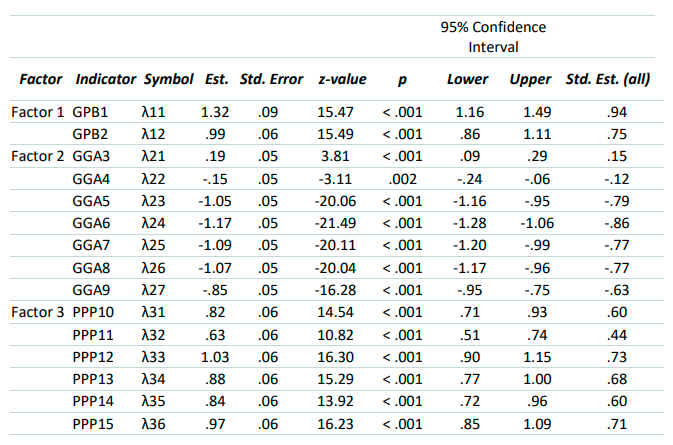

Evidence of validity based on the construct validity and internal structure and reliability

Next, the 15-item Puerto Rican POPS Spanish version underwent a CFA with SEM analysis to test the Model 1 (M1). The results indicate χ2 (87) = 97.922, p < .001 and the fit indices CFI = .99, TLI = .99, GFI= .98, IFI = 99, NFI = .96, SRMR = .07, RMSEA = .02 with RMSEA 90% CI lower bound (.00) and RMSEA 90% CI upper bound (.05) thresholds. See Table 3 the parameters estimate of the Model 1 (M1) and all factor loadings in the standard estimates.

Convergent, discriminant and concurrent validity and internal consistency

Next, each item's factor loadings were analyzed to examine the construct measures' internal convergent validity. The items had high factor loadings and were statistically significant. The Average Variance Extracted (AVE) was measured to test the convergent validity, and more than .50 indicates a construct validity. Afterward, the AVE's values were compared with the shared variance on each construct to determine the discriminant validity. The AVE's must indicate a higher value than the inter construct squared correlation, also called the MSV. The Composite Reliability (C.R.) measures the internal consistency of scale items, and more than .70 indicate statistically significant (Hair et al., 2014; Malhotra & Dash, 2011).

Next, performing convergent and discriminant validity in the 15-item Puerto Rican POPS Scale Spanish version, the analysis shows no violation and convergent and discriminant validity issues in factor one (General Political Behavior). However, factor two (Go Along to Get Ahead) and factor three (Pay and Promotion Policies) show that the AVE values were less than (.50). Nevertheless, the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) is not more than .50; Fornell and Larcker also said if AVE is less than .50, but more than .40 and if Composite Reliability (C.R.) is higher than .60, the convergent validity is still adequate (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Moreover, AVE less than .50 means that average item loading is less than.70, which explains that some factor loadings are good .60 (Hair et al., 2010). Therefore, the AVE was less than .50, but the C.R. was more than .60, so discriminant validity exists between the Puerto Rican POPS Scale Spanish version factors.

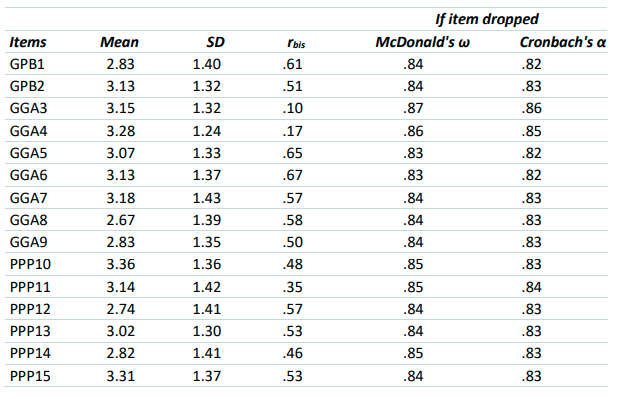

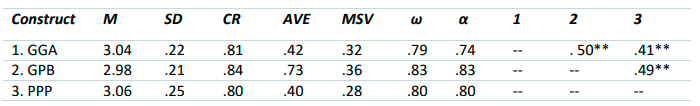

Moreover, the results show that the AVE's values fluctuate between .40 and .73, and the C.R. values fluctuate between .80 and .84. Next, a bivariate Pearson coefficient is used to test the internal concurrent validity of each construct in the 15-item Puerto Rican POPS Scale Spanish version. The final model is the 15-item Puerto Rican POPS Scale Spanish version using Cronbach's alpha formula and the McDonald's Omega to test the internal consistency. The entire 15-item Puerto Rican POPS Scale Spanish version has a Cronbach's alpha of .84 (mean = 3.04; standard deviation = .22) with a 95% Confidence Interval of lower bound of .81, and 95% Confidence Interval Upper bound of .87, and a McDonald's Omega of .85 with a 95% Confidence Interval lower bound of .82 and 95% Confidence Interval upper bound (.88). The dimensions of the 15-item Puerto Rican POPS Scale's Cronbach's alphas fluctuated between .74 to .83, and the McDonald's Omega fluctuated between .79 to .83. See Table 4 shows each dimension's Cronbach's alpha and McDonald's Omega, AVE and C.R., Mean and Standard Deviation, MSV, and the correlation by dimensions.

Table 4 Correlation matrix of CR and AVE with inter square correlation (n = 205).

Note: M = Mean; SD = Standard deviation; CR= Composite Reliability; AVE = Average Variance Extract; MSV = Maximum shared variance; α = Cronbach’s alpha; ω = McDonald's Omega; ** Correlation significant at a p < .001. The values on the diagonal represent the correlations between the latent factors (construct). GPB (General Political Behavior); GGA (Go Along to Get Ahead) and PPP (Pay and Promotion Policies).

Discrimination index and Internal consistency of scale items

Lastly, an analysis of the 15-item Puerto Rican POPS Scale Spanish version in Model 1 (M1), the discrimination indexes were analyzed greater than .30 using the corrected item-total correlation technique (Kline, 2005). All items comply with the recommended thresholds .30 except for item 3 and item 4. As for the internal consistency for each factor, the Cronbach's alpha coefficient and the McDonald's Omega show that all the items had adequate coefficients. Table 5 shows the corrected item-total correlation in the final 15-item Puerto Rican POPS Scale adapted Spanish version.

Discussion

This study examines the 15-item Puerto Rican POPS Scale Spanish version psychometric properties, a translated and adapted version from the 15-item POPS Scale English version and administrated in Puerto Rico that measures the phenomenon perceptions of organizational politics.

This study's implications show that the 15-item Puerto Rican POPS Scale Spanish version may be a valuable diagnostic tool for future research in the academic scientific community in Puerto Rico. Furthermore, the instrument may serve consultants, Industrial-Organizational Psychologists, and the business management discipline to conduct needs assessments. Finally, it may inspire interest and research in the darker side of workplace politics and unfair work policies in many Puerto Rican workforce sociocultural contexts.

Also, the 15-item Puerto Rican POPS Scale possesses adequate internal psychometric properties, confirming that the instrument can be applied in further research and tested in Puerto Rican organizations. Likewise, the 15-item POPS Scale English version is a widely used instrument applied in countless studies over the past years and proved to have significant results. Therefore, the 15-item Puerto Rican POPS Scale adapted Spanish version may also apply in future studies in Puerto Rico and Latin-speaking countries.

Another implication of this study, especially in managerial practice, may help the organizations and supervisors and managers gain a deeper understanding and concept of the workplace's cynical politics. Furthermore, they may learn to identify other vulnerable groups and prioritize possible intervention plans and new training. Likewise, this study may encourage self-awareness in the Human Resources Department and other managing departments to tackle unfair practices.

According to (Valle et al. 2019), the implications of organizational politics in the past three decades and the political perspective of organizational behavior helped understand political organizations' perceptions. In addition, there is extensive evidence and a strong relationship between work, the workplace environment, and other personal factors that motivate employees and organizations to act irrationally.

For the theoretical implications, it was possible to update and examine the psychometric properties of the 15-item POPS Scale English version to a 15-item Puerto Rican POPS Scale Spanish adapted version with robust statistics. This study may also contribute to new literature in Puerto Rico and better understand the phenomenon of organizational politics at the organizations. The 15-item Puerto Rican POPS Scale Spanish version details how employees perceive dirty work politics at work, such as unfair policies and nepotism. According to the literature, all three dimensions in the 15-item Puerto Rican POPS Scale Spanish version concord with the 15-item POPS Scale English version that measures the same latent constructs (Kacmar & Carlson, 1997). Thus, this study shows that the instrument measures and takes into account organizational politics' workplace behavior.

Notably, the analysis of confirmatory factors with the structural equation model supports the three-dimensional model; that is, the Puerto Rican POPS Scale Spanish version scores underlie three constructs supporting its internal structure. The Fit indices support the model since they were among acceptable values (e.g., Hair et al., 2014; Kline, 2016). Also, to calculate the average score of the scale. First, sum all of the items in the set and divide them by the number of items.

Another theoretical implication is the multidimensionality and the observed variables used to measure each dimension in the 15-item Puerto Rican POPS Scale Spanish version. It is essential to examine the construct validity and reliability, therefore confirming multidimensionality. In a theoretical model, the construct validity or the convergence of observed variables are closely related to the same latent variable. The discriminant validity of the non-related observed variables from other observed variables is associated with other latent variables (Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Kline, 2005). In other words, the 15-item Puerto Rican POPS Scale Spanish adapted version possesses a three-dimensional as in the 15-item POPS English version. In sum, the Puerto Rican POPS Scale Spanish version complies with the internal psychometric properties and the three-factor structure.

Finally, according to the literature review and the theoretical perspective, most researchers argue that political perceptions have many consequences on work behavior. There is a darker side of organizational behavior and a close relationship between perceptions of organizational politics and personal and work-related outcomes. Many authors mention that organizational politics negatively affect job dissatisfaction, produce stress, and increase job turnover. However, Valle et al. (2019) argue a gap in the literature review those perceptions of organizational politics do not only cause these negative factors. Other facets, such as unethical work behavior and moral disengagement in employees, may harm their socio-cognitive resources and demands.

Limitations of this study

One of the limitations of this study was the small sample size. Another limitation was the snowball sampling and non-probabilistic convenience recruitment method. As a result, the sample is not representative of the Puerto Rican working population. Although a sample size between 300 to 500 or more is appropriate in a Confirmatory Factor Analysis with Structural Equation Modeling, the larger the sample, the better the model fit. However, Chi-square is sensitive to large sample sizes, and that it would be difficult to reject the null hypothesis model (Brown, 2015; Bryne, 2016; Kline, 2016). Another limitation was that during the research, non-existing studies in Puerto Rico on the phenomenon of organizational politics to compare it with the Puerto Rican POPS Scale adapted version with other latent constructs similar to organizational politics to perform external convergent and discriminant analyses.

Another limitation was that many organizations declined to participate in this study. Moreover, some participants answered the instruments in an environment outside their office space and may have experience distractions such as noise, poor concentration, and external environmental distractions out of the researcher's and participants' control. Finally, the 15-item Puerto Rican POPS Scale Spanish version is only based on statistical data analysis and no prior hypothesis tested.

Recommendations

One of the first recommendations is to administrate the adapted version of the 15-item Puerto Rican POPS Scale Spanish version in a larger sample size in Puerto Rico and other municipalities to further test its construct validity and reliability. Also, test the 15-item adapted POPS Scale Spanish version with additional statistical analysis that was not in this study, for example, test-retest reliability and test criterion. In addition, perform an external convergent and discriminant analysis with other valid instruments if the 15-item Puerto Rican POPS Scale Spanish adapted version for the Puerto Rican sample measures the construct validity and reliability.

On the one hand, another method is to test the 15-item Puerto Rican POPS Scale Spanish version in other Latin-speaking countries to determine a sociolinguistic language barrier. On the other hand, if Latin countries perceive organizational politics in the working sector and determine the 15-item Puerto Rican POPS Scale, the Spanish version is valid in other Spanish-speaking countries. Furthermore, conduct longitudinal studies and a phenomenological approach on the perception of organizational politics in Puerto Rico. Also, perform new empirical research with other variables such as organizational silence, work ethics, cynicism, and other political behavior factors that affect employees' cognitive demands in the Puerto Rican working sectors. Lastly, item 3 and item 4 scored lower than .30, which suggests these two items may be measuring somewhat differently from the rest of the items in the scale, but in future studies, item 3 and item 4 need further revision, although the 15-item Puerto Rican POPS Scale Spanish version possesses a good internal consistency above .70 and the model has good fit indices.

Conclusion

The 15-item Puerto Rican POPS Scale Spanish adapted version may contribute to the scientific community in Puerto Rico. Especially in Human Resources, Industrial-Organizational Psychology, and other Business Management disciplines to better understand office politics' impact in the workplace and its repercussions on the organizations. The instrument seems to have reliable internal construct validity and reliability psychometric properties. In addition, the 15-item Puerto Rican POPS Scale Spanish version will be a helpful instrument in future studies to analyze the workforce in Puerto Rico. Historically, politics has played a role in the citizens of Puerto Rico's quotidian life, even in work, which may contribute to new theoretical insight into the Puerto Rican work culture.