Introduction

The new information and communication technologies (ICT) have allowed new forms of communication between people (Cooper et al., 2016; Döring, 2014; Gámez-Guadix et al., 2016). For example, 92% of adolescents between the ages of 13 and 17 reports using a cell phone and 24% indicates that they use it constantly (Lenhart, 2015). ICT have positive aspects, such as being more communicated, but they also generate negative behaviors (Holfeld & Grabe, 2012).

One negative online behavior by adolescents that has recently attracted the attention of researchers and the community is sexting (Quesada et al., 2018). Sexting is creation and exchange of text messages, videos, images, or photos with personal sexual content through the Internet, social networks, or cell phones. This phenomenon is called sexting (Agustina & Gómez-Durán, 2012; Barrense-Dias et al., 2018; Mitchell et al., 2012; Morelli et al., 2016). Sexting is a risk factor for the psychosocial adjustment of individuals, mainly in minors, such as children or adolescents. Among these risky behaviors, it can be mentioned the sensitive sexual type (Benotsch et al., 2012), which leads to a higher probability of suffering from cyberbullying (Crimmins & Seigfried-Spellar, 2014; Quesada et al, 2018; Reyns et al., 2013; Ricketts et al., 2014), increased consumption of toxic substances (Temple et al., 2014), depressive symptoms (Jasso Medrano et al., 2017) or suffering from sexual abuse (Kopecky, 2012), among others.

Sexting behavior is frequent in adolescents (Fleschler et al., 2013; Gámez-Guadix & Santiesteban, 2018; Gámez-Guadix et al., 2017; Mitchell et al., 2012; Strassberg et al., 2013). For example, recent systematic reviews in adolescents on the prevalence of sexting found a fluctuation between 7% and 27.6% (Barrense-Dias et al., 2018; Cooper et al., 2016). Regarding gender differences, some studies did not detect differences between men and women (Benotsch et al., 2012; Weisskirch & Delevi, 2011), while others found that more men than women carried out sexting (Baumgartner et al., 2014; Gámez-Guadix et al., 2015; Gámez-Guadix et al., 2017; Ybarra & Mitchell, 2014), with some studies detecting this also in Argentina (Resett, 2019). Finally, other studies found that these behaviors were higher in women (for example, Reyns et al., 2013). Age was also a widely examined variable, suggesting that sexting increases progressively with age throughout the adolescent period (Dake et al., 2012; Rice et al., 2012).

On the other hand, another of the great psychosocial risks for adolescents is that many of those who suffer sexting may also suffer other problems related to ICT, such as online grooming or cyberbullying (Wachs et al., 2012), although the interrelationships between these behaviors have practically not been investigated in the world (Machimbarrena et al., 2018). One of the few investigations in this regard found that those who suffered online grooming were also more likely to suffer from sexting (Machimbarrena et al., 2018). Online grooming is defined as a process through which an adult with ICT tries to gain the trust of a minor to create or maintain sexual contact online or - later - in person (Kloess et al., 2014; Smith et al., 2014; Wurtele & Kenny, 2016). The process of online grooming for minors by adults is made up of two aspects: solicitation by adults, on one hand, and online sexual interaction with them, on the other (Gámez-Guadix, De Santisteban, & Alcazar, 2017; Mitchell et al., 2007).

The difference in power between minors and adults can make adolescents more vulnerable to sexual contact with adults and to handle such contacts in an inappropriate way, due to the lack of cognitive and emotional maturation of minors (McRae et al., 2012; Wolak et al., 2010). For instance, it was found that adolescent depressive symptoms were associated with a higher risk of experiencing sexual solicitations by adults (Ybarra et al., 2004). Although online grooming can be perpetrated from one adolescent to another (Ybarra & Mitchell, 2008), it is psychosocially more negative when perpetrated by an adult (Wolak et al., 2010). Regarding the percentages of online grooming, the prevalence of sexual solicitation in the last year was 5-15% in adolescents aged 10 to 17 years in the United States and Europe (Bergen et al., 2015). Another study in the United States found similar figures with 9% of adolescents of the same age (Jones et al., 2012). Also, a study in the Netherlands with adolescents found that 6% of males suffered from it, while in females the figures rose to 19% (Baumgartner et al., 2010).

In addition to the association of sexting with demographic variables and grooming online, a factor also examined was personality (Delevi & Weisskirch, 2013). (Van Ouytsel et al. 2014) found that the sensation-seeking dimension increased the probability of engaging in sexting. (Temple et al. 2014) detected that greater impulsivity was related to a greater probability of sending images with sexual content. Although these two studies constitute a valuable starting point on the relationship between personality and sexting in adolescents, both are limited by the measures used, since in these works sexting was evaluated solely as the sending of images and with a single item. Further, both studies evaluated isolated dimensions of personality, for example, impulsivity or sensation-seeking.

The Dark Triad of Personality (Paulhus & Williams, 2002) is a recent approach to personality. Machiavellianism, psychopathy, and narcissism have been postulated as personality traits of this model (Furnham et al., 2013; Paulhus & Williams, 2002). These traits are aversive or negative but still within the normal range of functioning (Paulhus & Williams, 2002). For this reason, they do not have to suppose pathology for the individual. Thus, the exact terms for the constructs mentioned are Machiavellianism, subclinical narcissism (this trait should not be confused with clinical narcissism in Narcissistic Personality Disorder), and subclinical psychopathy (this trait should not be confused with clinical psychopathy), as (Buckels et al. 2013) pointed out. This approach as a whole can respond to a short-term social strategy, which seeks the exploitation of others (Jonason et al., 2009; Jonason et al., 2011), as indicated by the relationships between the dark personality with high levels of pleasantness (Jakobwitz & Egan, 2006; Jonason et al., 2009; Paulhus & Williams, 2002). Following this line, subclinical narcissism is divided into two: grandiose and vulnerable. Grandiose narcissism is characterized by exhibitionism, lack of humility and modesty, and interpersonal dominance; in contrast, in vulnerable narcissism, negative affect, mistrust, and the need for attention and recognition are paramount (Dickinson & Pincus, 2003; Miller et al., 2012). In addition, Machiavellianism is defined by a pattern of strategic thinking, manipulative skills, and insensitive pragmatism, where the desire for success shows control over impulsiveness (Miller et al., 2017). Finally, subclinical psychopathy is characterized by insensitivity, lack of empathy, impulsiveness, disinhibition, and meanness, being the most aversive construct within the dark triad due to its high correlation with antisocial behavior (Paulhus & Williams, 2002).

Although no investigations have been detected between the dark personality and sexting, if the latter behavior involves a new form of exchange with others, it is possible to hypothesize that it will be associated with the dark personality, mainly Machiavellianism. Many studies indicate the positive associations between this dimension with the motivations to court, as detected by (Jakobwitz and Egan, 2006) and (Jonason et al. 2009). The only study that explored the predictive value of dark personality to predict sexting in adolescents did so with linear regressions (Resett, 2019).

Emotional problems and dark personality vary by gender as women tend to score higher in depression and anxiety than men, mainly in adolescence, while men score higher in dark personality traits (Chiorri et al., 2019). Regarding sexting behavior and its association with emotional problems, many studies found that, at higher levels of sexting, higher scores in depression (Barrense-Dias et al., 2018; Jasso Medrano et al., 2017; Temple et al, 2014; Van Ouytsel et al., 2014). In a recent study with university students, it was detected that those who carried out sexting behaviors showed a higher level of depression and anxiety than those who did not (Gasso et al., 2020).

Regarding the different predictors of sexting according to gender, (Sevcíkova, 2016) found that the predictors of this behavior (alcohol consumption, emotional problems, self-efficacy and having had intercourse) in early adolescents varied according to gender. Alcohol consumption and emotional problems were predictors for both genders, while the other two were only predictors for males.

This study

Although sexting is beginning to be highly researched in Anglo-Saxon countries and even in Spanish-speaking nations -such as Spain-, studies in Latin American countries are almost non-existent to our knowledge. In this way, the advantages of the present work are: studying the sending of text, photos and images -many studies used only photos-, on one hand, and the variables and their relationships will be evaluated with a model of structural equations, on the other, which, unlike multiple or logistic linear regressions, has the advantages of being able to use latent variables, both exogenous and endogenous, as it more complexly evaluates the relationships between the variables (Kline, 2015). Also, another advantage is that examining whether there are different predictors according to gender will be evaluated with this model.

Thus, the objectives of the present study were:

explore sexting and if it varies according to gender and age;

investigating whether dark personality and emotional problems were predictors of sexting in a sample of Argentinean adolescents separately for males and females;

to examine from a structural model if emotional problems (depression and anxiety) and dark personality are predictors of sexting and online grooming, as well as if sexting is a predictor of online grooming.

determine if said model is invariant according to gender.

Hypothesis

More men engage in sexting than women. Older age, more sexting behaviors in adolescents.

Dark personality and emotional problems scores are significant predictors of sexting. Gender is a moderating factor in this regard.

Regarding the structural model, emotional problems and dark personality scores are significant predictors of sexting and grooming. Sexting is a significant predictor of grooming.

This structural model is not invariant according to gender.

Method

Participants

An intentional sample of 728 adolescents between 11 and 18 years old was constituted (38% were males; M age = 14.27 years, SD = 1.79). The adolescents were studying from the first year to the fifth year of three private secondary schools in the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires and Paraná, Argentina. The first city is the capital of the country, which is why it represents a large population conglomerate, while the second is a medium-sized city located 450 kilometers from the national capital. Most adolescents reported that their parents were married or living together (64%). This was inquired in order to determine if this residential status could introduce differences in sexting or grooming to be examined in future studies.

Instruments

Socio-demographic questionnaire . Gender, age, grade, parents residing together or not.

Sexting questionnaire (Gámez-Guadix et al., 2015). This instrument evaluates the frequency that adolescents send sexual content online. This questionnaire asks participants to indicate how many times they have voluntarily done the following: 1) “Send written information or text messages with sexual content about you”; 2) “Send photos with sexual content (for example, nude) about you”; and 3) "Send images (for example, via webcam) or videos with sexual content about you". The response options are: 0 = never; 1 = 1 to 3 times; 2 = 4 to 10 times; and 3 = more than 10 times. Prevalence is calculated considering, at least, those participants who mark the option 1 to 3 times or more. Furthermore, to obtain more accurate information on the times that sexting is carried out; the average chronicity can be calculated. Chronicity implies the average number of times that it occurs among those who presented the behavior in question on at least one occasion (e. g., Straus & Ramirez, 2007). In this case, the chronicity is calculated for those participants who mark the option 1 to 3 times or more. It is also possible to derive a sexting index by adding or averaging the questions. This scale has shown adequate construct validity in Spanish samples (Gámez-Guadix et al., 2015) and adequate internal consistency (Cronbach's α) with an index of 0.71 (Gámez-Guadix et al., 2017). In the present sample, Cronbach's α was 0.86.

Questionnaire for Online Sexual Solicitation and Interaction of Minors with Adults (QOSSIA, Gámez-Guadix, Santisteban, & Alcazar, 2017). This 10-item questionnaire asks adolescents to indicate how often they experienced a sexual request or interaction with a subject 18 years of age or older in the past year, using a four-point Likert scale: 0 (never), 1 (one once or twice), 2 (3-5 times) and 3 (6 or more times). Inquiries about last year to avoid time bias due to longer periods and because that period has been used in previous questionnaires on similar topics (e. g., Jones et al., 2012). Concerning its psychometric properties, studies in samples of Spanish adolescents indicated an adequate factorial structure with two factors; one called sexual solicitations and the other, sexual interactions. The first consisted of the first five questions that refer to sexual requests by an adult towards the minor (for example, “An adult asked me for pictures or videos of myself with sexual content”) and the other consisted of the rest, which inquiries about intentions on the part of the adult to commit sexual abuse of the minor (for example, “I’ve met in person an adult I previously met on the Internet”). It presents an adequate factorial structure and internal consistency in Argentina (Resett, 2021). In the present sample, Cronbach's α was 0.90 for request and 0.88 for interactions.

Rosenberg Scale of Psychosomatic Symptoms (RPS, Rosenberg, 1965). The 10 items of the RPS measure anxiety based on the activation of the autonomic nervous system (Rosenberg, 1965). Responses are scored on a scale from 0 (Never) to 3 (Many times). Questions are totaled and higher scores indicate greater anxiety. In Argentina, Cronbach's αs fluctuated from 0.74 to 0.78 (Facio et al., 2006). In the present study, α was 0.84.

The Kovacs Depression Inventory for Children (CDI, Kovacs, 1992). CDI is one of the most used inventories to measure depression and is made up of 27 items. Each one consists of three statements with a grading of severity of depressive symptoms from 0 to 2. CDI has good properties (Kovacs, 1992). Responses are totaled and higher scores indicate greater depression. In Argentina, Cronbach's αs fluctuated from 0.86 to 0.89 (Facio et al., 2006). In the present sample, α was 0.83.

The Dirty Dozen (DD, Jonason & Webster, 2010). The DD is a 12-item instrument divided into three subscales to each measure a feature of the dark triad: Machiavellianism, Psychopathy, and Narcissism. It is divided into four items by subscale and uses a seven-option Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). Machiavellianism consists of the manipulation and exploitation of other people. Narcissism consists of excessive grandeur or admiration for oneself. Psychopathy is characterized by low empathy, impulsiveness, and antisocial behavior. Examples of questions are: "I tend to manipulate others to get my way" (Machiavellianism), "I tend to lack remorse" (psychopathy), and "I tend to want others to admire me" (narcissism). This instrument presents good factor structure, reliability, and convergent and discriminant validity in the first world (Jonason & Webster, 2010), as in Spanish-speaking samples (Nohales Nieto, 2015; Copez Lonzoy et al., 2019). The Spanish version of (Nohales Nieto, 2015) was used in this research. In the present sample, Cronbach's αs were 0.77, 0.72 and 0.84, respectively.

Procedure

The purpose of this research was explained to school principals and parents. After obtaining the consent of the school, and the parents, participants were informed of the purpose and voluntary participation, anonymity and confidentiality were guaranteed. An informed consent was signed by parents, schools, and participants. The students filled out the questionnaires in the hours that the school set aside for this purpose. Questionnaires were applied by the authors of this manuscript.

Data analysis

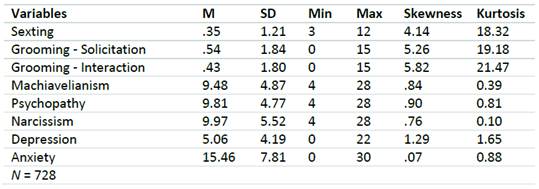

Data were analyzed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 24 to process descriptive (percentages, means, etc.) and inferential statistics (χ², tests of means, linear regressions in blocks, etc.). For the objective of determining whether gender and age introduced differences for sexting, the variances were homogeneous for both genders p <.756 concerning the sexting scores and there were differences in the variances according to age (these were grouped in early adolescents 11-13 years, middle adolescents 14-15 and late adolescents 16-17), although marginally p <.06. Therefore, it was decided to use parametric statistics. χ² to determine if gender introduced differences in each of the questions (prevalence) and ANOVA (univariate analysis of variance) for the total score, placing gender as a factor between subjects and age (group). Multiple linear regressions using enter method were carried out placing gender (dummy variable 0 = male and 1 = female) and ages (ages 11 to 17), depression, anxiety, solicitude, interaction, psychopathy, Machiavellianism, and narcissism scores separately for men and women to find out if there were different predictors for this behavior. A significance level of p .05 was taken, which is the one commonly used in social sciences. The MPLUS 7 program was used for the structural models with an MLM procedure because of the data deviated from normality, mostly for the sexting and grooming scores. A kurtosis value greater than 2 is considered far from normal (for example, Boomsma & Hoogland, 2001; Byrne, 2012), while asymmetry values greater than 3 and kurtosis of 8 to 20 or more are considered extreme (Kline, 2015).

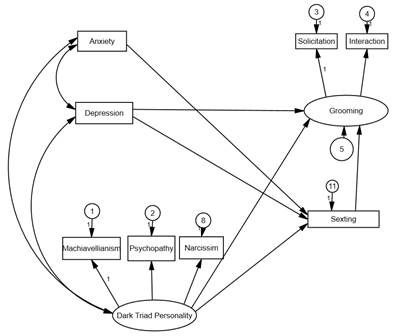

To consider the fit of the model adequate the CFI, TLI, RMSEA and SRMR were taken into account (Byrne, 2010, 2012). CFI and TLI values above 0.90 and RMSEA and SRMR below 0.10 are adequate (Bentler, 1992; Byrne, 2010). Although there are more demanding criteria of CFI and TLI greater than 0.95 and RMSEA and SRMR less than 0.05 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Currently, CFI criteria greater than 0.97 and RSMEA and SRMR less than 0.07 are postulated (Hair et al., 2010). That the χ² is not significant is a very demanding criterion and sensitive to the size of the sample (Byrne, 2010), so it was not taken into account to evaluate the fit. However, some authors suggest that χ² can be divided by the degrees of freedom with values obtained less than 2 or 3 as being acceptable (Cupani, 2012). To determine whether the model was invariant according to gender, it was considered whether ∆χ² was significant as well as whether the ∆CFI was above p > 0.01 (Byrne, 2012). For this analysis, the guidelines of (Byrne, 2012) were followed, which establishes first to determine a configurational model and then to constrain it and verify if there is structural invariance or not. Paths and covariances were constrained. The errors of the observable indicators were not constricted since it is rarely carried out (Byrne, 2012). The model to be tested is shown in Figure 1.

Results

Table 1 shows the descriptions for the variables. As shown in Table 1, grooming - solicitation presented higher levels than grooming - interaction. Regarding the dark triad of personality, narcissism presented the highest scores, while for emotional problems, anxiety showed the highest levels.

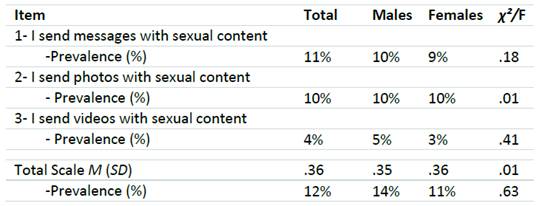

Table 2 shows the prevalence of each type of sexting and for the total score for this behavior. The total prevalence was 12%. No differences emerged neither in each of the questions nor in the total score as perceived in Table 2.

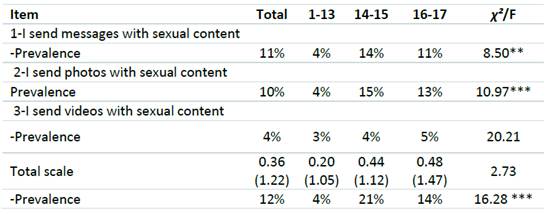

With regard to prevalence by age, Table 3 shows the percentage of adolescents who were involved in some type of sexting according to age and for the total score. As shown in the table, there were age differences in the question of sending messages of sexual content and in sending photos. As can be seen, the two oldest age groups practiced sexting to a greater extent than the 11-13 years old.

Table 3 Prevalence and chronicity of sexting according to age in adolescents.

*** p <0 .001 ** p <0.01

To determine which of the variables were the most significant predictors of sexting, regressions were performed to predict scores on sexting separately for males and females. IFV values were adequate, as they were below 4 and barely exceeded a value of 1 (from 1.32 to 1.99). This suggested that there were no indications of multicollinearity (Field, 2009).

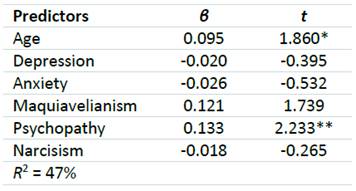

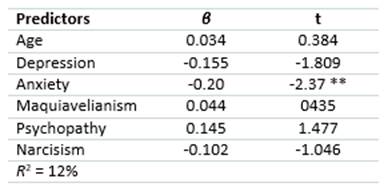

The results are shown in Table 4 for females and Table 5 for males. As shown in Table 4, the equation explained a variance of R2 = 47% in females with the prediction equation being significant p < 0.001. In the case of males, a variance of R2 = 12% was explained, as shown in Table 5, with the prediction equation being significant p < 0.001. In the case of females, older age and scores psychopathy were the significant predictors. In the case of males, less anxiety was the significant predictors.

Table 4 Multiple lineal regressions for sexting prediction with age, emotional problems and dark personality in females.

** p < 0.03 * p < 0.05

Table 5 Multiple lineal regressions for sexting prediction with age, emotional problems and dark personality in males.

** p < 0.02

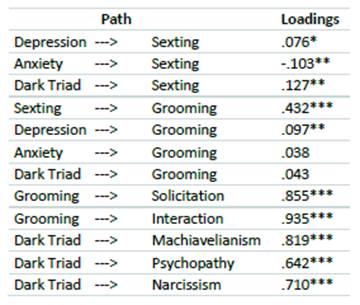

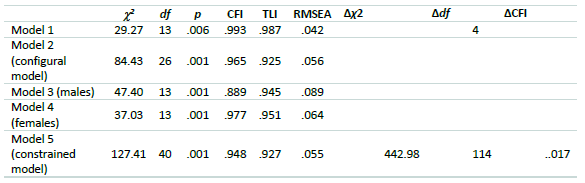

Finally, the postulated model to predict sexting and grooming with dark personality, depression and anxiety as exogenous variables was tested. As shown in the Table 6, a satisfactory fit was found for said model. Although the χ² was significant, when divided by the degrees of freedom this was 2.25.

Table 6 Goodness of fit statistics of the different models.

Note. df = degrees of freedom. CFI = Comparative Fix Index. TLI = Tucker-Lewis Index. RMSEA = root mean square of residuals. SRMR = standardized root mean square of residuals. ∆χ2 = difference in χ2 between models. ∆df = difference in degrees of freedom between models. ∆CFI = difference of CFI between

As shown in the Table 7, depression scores were significant predictors of grooming and so were sexting. Regarding sexting, both depression, anxiety and dark personality scores were significant. Neither anxiety nor dark personality were predictors of grooming. The model explained a variance of 6% for sexting and 21% for grooming. Finally, a structural invariance analysis of said model was carried out for men and women. As shown in Table 6, the adjustment for men and women was satisfactory, although it was more so for the latter group. With respect to the configurational model, the fit was satisfactory too. When testing the constrained model -in which the paths of the structural model were used, the measurement ones and the covariances were set-, as shown in the Table 6, the difference in ∆χ2 was significant at the p < .001 level and the ∆ CFI was > .01 which suggested that the model was not invariant according to gender. Next, the different segments of the model began to be constrained to determine where the non-invariance was. It was found that this lay in the path of sexting to online grooming according to ∆χ = 28.50 df = 1, and the value ∆CFI = 0.02. Similarly, the path of machiavellianism and anxiety toward sexting were not invariant. Due to this interesting result, a linear regression was carried out to predict solicitation and interactions from sexting for men and women. With respect to males, the prediction of the solicitation was not significant R2 = 0.01% p < .204, for the interactions it was significant R2 = 6% β = 0.26 t = 3.04 p < .003. For women, a significant proportion of variance were explained both for solicitation and interactions R2 = 40% β = 0.64 t = 12.02 p < .001 and R2 = 39% β = 0.63 t = 11.95 p < .003, respectively.

Discussion

The findings of the present study indicated that sexting represents a habitual way of relating sexually through ICT among adolescents. The 12% of adolescents between 11 and 17 years old admitted having carried out a sexting behavior on at least one occasion. The most frequent ways were to send written messages of a sexual nature (11%) and photos (10%), and then videos followed, in order of frequency (4%). These data were similar to those from meta-analytic investigations with adolescents who have reported prevalence between 2.5% and 27% (e.g., Cooper et al., 2016; Döring, 2014). A study in Spain (Gámez-Guadix et al., 2017) that used the same instrument employed here detected percentages of written information of 11%, a shipment of sexual photos of 7%, a shipment of videos of 2%, and a total of 14%. Therefore, the results found in the present sample of Argentine adolescents were quite similar. Another study in Argentina with adolescents detected slightly higher percentages with a total of 21%. The most frequent forms were 17% of sending written messages of a sexual nature, 18% of photos and 6% for videos (Resett, 2019). Although the instrument was the same, the age ranges were different since in this research they were 13-18 years old.

Interestingly, in the present study no differences were detected according to gender with respect to this behavior. The results found here are consistent with some studies (Benotsch et al., 2012; Weisskirch & Delevi, 2011). However, evidence in this respect is inconsistent, while others found that more men than women carried out sexting (Gámez-Guadix et al., 2017; Resett, 2019; Ybarra & Mitchell, 2014). Similarly, other studies found that these behaviors were higher in women (Reyns et al., 2013). These results would not support the hypothesis that men perform more sexting behaviors. More research is needed to determine the complex difference in this regard.

Regarding sexting according to age, it was detected that total grooming increased from 4% at 11-13 years old, to 21% at 14-15 years old to 16-17 years old. There were also differences in this respect for written messages and photos, but not for videos. In the total score, the differences were marginally significant. Thus, these results were similar to studies with North American samples (Dake et al., 2012), Spanish samples (Gámez-Guadix et al., 2017), and Argentinean samples (Resett, 2019). These results would confirm the hypothesis that, at older ages, higher scores for this behavior.

The last purpose of the present work was to determine if dark personality and emotional problems were significant predictors for sexting for men and women. A prediction of 39% was obtained for females and 12% for males. Hence, a much larger variance was predicted for women than for men. On the other hand, the predictors were also different for both groups. In the case of women, the significant predictors were age -older age, more levels of sexting- and psychopathy. In the case of their male peers, a lower level of anxiety was the factor that explained the variance. Some studies found predictors that were also different according to gender (Gasso et al., 2020; Sevcíkova, 2016). That psychopathy has been one of the main predictors for women adolescent may be because women with high levels of such content send it as a way to manipulate, exploit or seduce other peers for various purposes. It is known that women are more likely to use social networks for communication or interpersonal purposes. Therefore, perhaps those adolescents with a tendency to manipulate others use sexting for this purpose. Some research showed that high scores on dark personality were associated with greater internet addiction (Kircaburun & Griffiths, 2018; Sinderman et al., 2018). Psychopathy -the most harmful dimension of the dark personality- refers to being insensitive or cynical concerning the needs of others (Paulhus & Williams, 2002), which is why its association with sexting is not striking. These results are not impressive, since it is proven that in virtual relationships -with the superficiality of contact- people with traits with low pleasantness and with a tendency to exploit others feel comfortable.

Unlike other studies that found an association between this variable and higher levels of emotional problems (Barrense-Dias et al., 2018; Jasso Medrano et al., 2017; Temple et al, 2014; Van Ouytsel et al., 2014), neither for men nor women were detected that higher levels of depression and anxiety were predictors of sexting. Many authors point out that sexting could constitute a form of interpersonal relationship (Döring, 2014). Along these lines, in the case of men, low levels of emotional problems -less anxiety- were the predictors in this regard. Some studies found that high levels of perceived self-efficacy predicted this behavior. Possibly for them, a confident image, confidence, and low levels of emotional problems are associated with sharing this type of content. (Sevcíkova, 2016) found that in men, but not in women, high levels of perceived self-confidence and having had sex were predictors of sexting. Perhaps, men who have already had sexual experiences - achieving greater self-confidence and a more positive image of themselves - carry out more sexting. It should be examined why age is a predictor in women but not in men. Perhaps in men, a factor to send these contents is not age, but the level of sexual experimentation acquired.

Regarding the structural model to predict sexting and grooming based on dark personality and emotional problems, a model with a satisfactory fit was found. High levels of dark personality, lower levels of anxiety, and high depression scores -albeit marginally- were the significant predictors. For grooming, only higher sexting and depression scores explained the variance. These results support the hypothesis that dark personality scores and problems are significant predictors of sexting and grooming, as well as that sexting is a predictor of grooming.

It was found that the structural model was not invariant according to gender. Interestingly, one of the pathways that were not invariant was from sexting to grooming. Subsequently, when carrying out a linear regression analysis to predict the interactions and requests for men and women, it was observed that sexting was a large predictor for the scores of these two variables while, in the case of men, it was not for requests and was small for interactions. This would imply that adolescent girls who carry out sexting behaviors are much more exposed to abuse by adults, compared to boys. As many of the pedophiles are adult males, they may feel more attracted to the opposite sex and more if they are minors who due to their immaturity are more easily manipulated or extorted (Murray, 1998). (Sevcíkova, 2016) also found that the costs of sexting were lower for young male adolescents. This does not imply minimizing the costs of sexting for men. Evidence was also found for the hypothesis that gender was a moderating factor in the relationship between dark personality and sexting and that the structural model was not gender-invariant. This study has several limitations. First, the results cannot be generalized to the entire adolescent population because they worked with an intentional sample. Second, the research design was descriptive-correlational and cross-sectional. Finally, another limitation is that the self-report was used as the data collection technique.

Future studies should be with a sample of adolescents of a larger size, randomly collected and with a longitudinal design, which would allow us to determine what the directionality of the variables is like since it is possible that, for example, emotional problems or traits of dark personalities are precedent for this behavior, as well as increased sexting behaviors slowly leading to an increase in dark personality or a decrease in emotional problems.