1. Introduction

Foreign languages play a fundamental role in exchanges pertaining to the spheres of cultural, social, and economic life; in an international context, where English stands out as the most influential international language worldwide (Chumaña-Suquillo et al., 2017; Temizkan & Temizkan, 2014; Vugman, Casinelli & Lizárraga, 2019), followed by Spanish and Chinese (Chumaña-Suquillo et al., 2017). Such is the case of tourism, an activity of which its use of English especially is essential to the provision of services (Amirbakzadeh & Alroaia, 2020; Chumaña-Suquillo, Llano-Zhinin & Cazar-Costales, 2017; Manyoma-Ledesma & Barrio-Vargas, 2011; Temizkan & Temizkan, 2014). As Amirbakzadeh & Alroaia (2020) point out, a foreign language has a crucial role to play in the management of these services in order to generate understandable communication with visitors that do not speak the native language, and thus creating better international relations.

Vugman-Casinelli & Lizárraga (2019), explain that, for English in tourism, communication skills in casual contexts are needed, both verbal and written. Since customer service predominates in touristic services, through personal exchanges, the language and tongue, the manner and the abilities of the service providers are of utmost importance (Temizkan & Temizkan, 2014).

However, in so-called developing countries, where tourism is an especially important industrial sector, human resources and qualified services are still insufficient (Manyoma-Ledesma & Barrio-Vargas, 2011; Temizkan & Temizkan, 2014). This situation also occurs in Colombia, like in Cartagena for example, Colombia’s most touristic city (Manyoma-Ledesma & Barrio-Vargas, 2011). Several authors (Amirbakzadeh & Alroaia, 2020; Manyoma-Ledesma & Barrios-Vargas,2011; Temizkan & Temizkan, 2014), state that some of the skills that professionals and students in tourism must strengthen are those required for the provision of services, such as communication skills and proficiency in a foreign language. The use of a foreign language, as the authors state, is a factor that determines the range a profession can boast. Manyoma-Ledesma & Barrios-Vargas (2011), explain how, for instance, in the case of taxi drivers in Cartagena, when lacking English communication skills, they use strategies such as communicating through drawings, or a guide given by the Cartagena Tourism Corporation, or simply gestures when communicating with non-Spanish speaking foreign tourists.

In this paper, we will cover some of the results of a needs assessment for languages (foreign and native) in the department of Antioquia, Colombia. In particular, we focus on the results related to such needs within the context of the tourism sector. Based on the premise that languages are of vital importance in cultural, social, academic, and economic activities within a region, we started a study in 2020 with the goal of identifying needs in terms of public education, professional training and development of language teachers, as well as translation, and interpretation.

In this study, we assume that the department of Antioquia is a multilingual territory, i.e., a place where different languages co-exist (Cervantes Virtual Center, 2008), but where Spanish-English bilingualism has been promoted for decades, and where multilingual citizens (those with skills in two or more languages) have some needs that have not been met.

If we note the contrasting status that different foreign and native languages enjoy in the Colombian context, we know that among foreign communication languages, English boasts the status of lingua franca, that is to say, a language that serves as a bridge between people that do not share the same native language nor a common national identity, and choose English as the foreign communication language (Firth, 1996, as cited in House, 2003).

As was previously mentioned, for the purposes of this paper, we will focus on the needs for language skills in tourism development, as it is a sector with great potential for development in the department, and seemingly, the country as well. The tourism-language relationship was a recurrent theme in the data analysis for all the department’s subregions; the municipal development plans showed that Antioquia is making a huge investment in tourism, especially after the peace accords. Undoubtedly, the number of foreign tourists is on the rise, at a rate unparalleled to the development of skills in the municipalities to meet demand, in our case specifically, in terms of foreign languages.

It’s worth emphasizing that the goal of this exploratory study focused on the needs of foreign languages within the development framework of the different sectors of Antioquenian society. As such, the findings presented here are analyzed from this point of view, in relation to the tourism sector. We highlight the findings related to this sector since the data reflected the importance of strategic planning in tourism to better use the territory’s own resources and the knowledge of its inhabitants, as well as the importance of languages for the strengthening of touristic activity.

Next, we will broadly describe the context of tourism in Antioquia as a framework for the findings of our language needs assessment related to this sector. We present the design of this study, and the conclusions we wish to highlight, as well as recommendations for international tourism planning.

2. Methodology

2.1 Context

The interest in bolstering tourism in Antioquia goes back a couple of decades. Brida et al. (2010), explain that towards the end of the 90s and the beginning of the 21st century, the tourism sector was gravely affected by the department’s social situation, on account of public order and armed conflict issues, which generated a great deal of mistrust between potential national and international tourists. Thus, between 2001 and 2004, a series of initiatives from the department government began being developed to promote tourism. For example, Medellín, the capital of Antioquia, has been positioning itself as the “high-class destination for fairs, congresses, conventions, and events in Latin America” (Brida et al., 2010, Section 2.2., par. 4). By virtue of this, a great portion of touristic activity is centered in the city.

With the COVID-19 pandemic, tourism was one of the most affected activities in Antioquia and the rest of the world. The table 1 shows, for instance, how the entry of foreign tourists was rising and the way it dropped dramatically in 2020:

Table 1 Number of non-residential visitors that entered the department of Antioquia between 2017 and 2021 (Center of Touristic Information, CITUR, 2022).

| Indicator | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | Growth%18/17 | Growth%19/18 | Growth%20/19 | Growth %21/20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-residential visitors | 333.572 | 379.102 | 438.530 | 138.351 | 183.433 | 14% | 16% | -68% | 33% |

The authors concur with Muñoz-Arroyave (2017), in his view that tourism goes beyond boosting economic growth, as we find it can effectively transform territories as well. Our findings show that the most recent tourism policies in the department are especially oriented towards counteracting the effects of the pandemic. As expressed in an El Tiempo newspaper article, they are “rescuing the territory’s potential and traditions, giving them touristic value” (Ramírez, 2022).

In fact, in March of 2021, the Secretariat of Tourism for Antioquia was created, “which will energize and strengthen this economic sector for all of Antioquia’s subregions” (Antioquia Informa, 2021). This secretariat, allied with another department government strategy called “Antioquia is Magic” (https://turismoantioquia.travel/antioquia-es-magica/), seeks to prepare youths in the region so that they stay in their territories, expanding tourism-related activities there. Other entities have joined this strategy, such as Corantioquia, Cornare and Corpurabá, the nine subregional touristic corporations, and the three family compensation funds operating in Antioquia.

This perspective of tourism in terms of the territory is an issue that we saw reflected in the results of our study, both in the interest of the communities and their governments. Despite the great potential of the municipalities, there is limited installed capacity to serve visitors, especially foreigners, but despite the pandemic, great interest in showing the world the richness of the territories persists. Due to the above, our purpose is to provide a critical reading of contexts, under the understanding that it is necessary to design and develop language programs and projects in line with the vocation of the territories. This will result in significant learning processes and relevant language services that contribute to the social, cultural and economic development of the territories.

Our analysis was structured according to Antioquia’s nine subregions, which contain its 125 municipalities: Urabá, Magdalena Medio, Occidente, Bajo Cauca, Norte, Nordeste, Oriente, Suroeste, and Valle de Aburrá; next, we will describe the characteristics of this context concerning tourism. Firstly, the Urabá region has the luxury of being bordered by the sea and its great expanse; its economic activities include agroindustry and tourism. In the case of the latter, the region boasts conditions for ecotourism and beach tourism, and faces challenges related to its vocation such as an exit and entry port for connections to domestic and international destinations. The Nordeste region stands out for being a major gold producer and having been heavily affected by the armed conflict, along with the absence of the State. Regarding tourism, it’s an underdeveloped and neglected sector; nonetheless, some municipalities plan to implement touristic development projects.

Bajo Cauca, acknowledged for its dedication to mining and raising livestock, has a tourism agenda with enormous potential for natural tourism, as well as for the design and execution of touristic products particular to the region, as seen reflected in the action plans of some of its municipalities. As for Magdalena Medio, tourism is mainly centered in Puerto Triunfo, which offers adventure tourism and ecotourism, given its proximity to the Magdalena River and the Claro River canyon. The Occidente region, with the perk of being close to the Cauca River, has focused its economic activities on historical, ecological, agricultural, recreative and/or business tourism, due to the colonial infrastructure of some of its municipalities, along with the different altitudinal zones.

The Oriente region is second in importance only to Valle del Aburrá. Regarding tourism, it’s an important destination for nature, medical and religious tourism. Furthermore, the interference of international markets, the settling of big companies that create jobs for its inhabitants, and the interest in international cooperation have created opportunities for international tourism. The Suroeste region, a territory known for its special coffees-based economy and exportation, has also created new ecotourism projects, owing thanks to its climate, rich biodiversity and natural resources. Lastly, Medellin and the Valle de Aburrá stand out above the other subregions on account of its great economic development, its population and quality of life. The manufacturing industry, the financial and business services are the main economic activities, and business tourism has increased steadily over the last few years, in partnership with public and private entities.

Thus, we can see why the department of Antioquia possesses a strong touristic vocation, which is tightly linked to its geographic traits, as well as the economic and cultural features of every one of its subregions.

2.2 Methods

In this qualitative needs assessment, data was gathered from the study’s participants, diverse in sources, regions, and sectors of society. The data collection process was developed in the following three phases:

First phase: document analysis. At the beginning of the research project, documents that could contribute to a preliminary profiling of needs related to plurilingualism were identified, at a departmental and municipal level. The investigation reports concerning the project topic were first analyzed. Then in a second phase, we identified, gathered, and analyzed the municipal development plans published up to date, which is to say, 113 municipal development plans, including Antioquia’s development plan. In both types of documents, we found indicators of needs regarding plurilingualism, as well as a need to strengthen tourism in those municipalities.

Second phase: Territory Actors Survey. A survey was conducted, designed, and sent via Google Forms (Google Surveys, 2020) to a database of territory actors in the education, government, and general community sectors, who could contribute key information regarding this research project’s focus, plurilingualism needs. This survey profiled the surveyee’s in terms of their region and sector, their uses of foreign languages and their contexts, the projects, or initiatives regarding the promotion of foreign languages, the teacher training opportunities in foreign languages, as well as the supply and demand of translation and interpretation services. Lastly, inquiries were made concerning projects or initiatives regarding native or Colombian creole languages.

Two-hundred and forty-four (244) answers were collected: 146 from the education sector, 46 from the government sector, 40 from the production sector (businesspeople, suppliers, agricultural cooperative leaders, etc.) and 12 members of civil society. This survey was conducted at the beginning of 2020; as such, some answers were received during the quarantine period for COVID-19. Evidently, the pandemic had a negative effect on the data collection, since the moment it was sent overlapped with a period of uncertainty and confusion that may have demotivated the participants. Unfortunately, we did not receive the expected number of answers; thus, we could not obtain a representative sample of the previously identified populace, nor a proportionate one with regard to the different sectors, despite having used different strategies to increase the number of answers. We clarify that despite the purpose of this survey not having been centered on tourism development, various sectors’ participants frequently indicated matters that linked languages to tourism.

Third phase: Interviews with Key Actors. Given the context of the pandemic, individual (13) and group (5) interviews were carried out virtually, via platforms like Google Meet and Zoom. The interviewees were selected using the purposeful sampling method (Patton, 2002), since they are cases of rich and enlightening information on plurilingualism or bilingualism-related needs in their region or sector. The interviewees possessed deep knowledge of their sector and their territory, or of the territories in which the organization or company they represent operate from (i.e., they could speak about all the subregions their organization is present in); some of them mentioned the development of tourism when talking about foreign language needs.

The purpose of these interviews was to delve into and complement the information garnered from the different audiences through the survey. Our expectations were to achieve a greater number of focus groups with representatives from different sectors, but, mostly due to the pandemic, we were not successful in the endeavor and had to resort to individual interviews.

The combination of the data obtained from the different information sources, along with a few validation and verification meetings with the communities, allowed for a general view of plurilingualism needs in Antioquia (see Echeverri-Sucerquia et al., 2022 for the full report), although this paper, as previously mentioned, focuses only on those related to tourism.

The data analysis process was conducted in simultaneously to the data collection, and was carried out both deductively and inductively: even though we used the research questions to generate preliminary analysis categories, these were weeded out during the span of the project, and were used as a foundation to organize the data using NVivo® software (March, 2020). The initial categories were: training, translation and interpretation, internationalization, and interaction with local non-Spanish speaking communities.

From the analysis of these preliminary categories, a few others emerged, of which we highlight, in this article, the two that relate to tourism. We found that tourism, as one of the sectors that presented the greatest need for foreign language use, has a dominating role in the development of different economic sectors, which is not only demonstrated by the municipalities’ development plans, but also by the different actors that participated in the study. At the same time, the use of foreign languages, especially English, has a crucial impact on the possibilities of communication between the touristic operators and the non-Spanish speaking visitors. Therefore, based on the findings, we propose the growing importance of tourism in the development plans and the need to develop and/or strengthen a tourism agenda and pre-existent tourism projects in the municipalities. Afterwards, we couple this topic with the relationship established by some participants between languages and tourism.

3. Results and discussion

Although our study did not particularly focus on the development of tourism, we did not wish to ignore the findings that pointed to tourism as a central axis for the economic growth and development of Antioquia’s different territories. Their development of tourism, and especially, that which attracts foreigners to each region, is of great interest to the improvement of the regional economy; because of this, different municipalities invest in the optimization of each region’s distinct products and services, in the generation of jobs, and new business ventures.

3.1 Strategic tourism planning in Antioquia’s regions, for building and boosting the territory as a tourist destination

Polo-Tovar (2019), proposes that planning tourism activity favors the increase of positive culture impact “in the economic and social development of the municipality, supporting local sustainable development through its economic impact” (p. 209). Both in municipalities with a well-known trajectory as well as those just starting out in the tourism sector, we find development plans that project strategic tourism planning. So what does the municipal tourism planning focus on? Figure 1 highlights several things, municipalities with programs and/or bilingualism indicators in their 2020-2023 development plans are outlined in black, while the stars indicate established programs and/or indicators for English being taught at public schools, whether for teachers or elementary, middle school or high school students, and the gray areas indicate a direct investment in the tourism sector by their development plans.

Figure 1 Map of Antioquia, with municipalities that stand out for including tourism projects and bilingualism in their development plans.

In regions like Norte, tourism development has been limited compared to other regions of Antioquia; a sizable number of its municipalities (Belmira, Campamento, Angostura, Donmatías, Gómez Plata, Guadalupe, Valdivia, Santa Rosa de Osos, and Ituango) projects the implementation of policies, plans, projects, and strategies for the promotion of tourism, and the creation of tourism plans based on the geographic diversity pertaining to each zone. These municipalities aim for the development of programs that help promote institutional management of tourism, tourism development planning processes, and communication strategies for the promotion of the territory as a destination for visitors.

On the other hand, in the Occidente region, municipalities like Sopetrán, San Jerónimo, and Santafé stand out for their high touristic development; regardless, their governments established projects and initiatives for the strengthening of this sector in their territories, and they propose organizing touristic activity by incorporating other activities such as birdwatching, extreme sports, and the formalization of tourism service providers. There is also the case of other municipalities (Abriaquí, Anzá, Yalí, Armenia, Buriticá, Caicedo, Campamento, Entrerríos, Heliconia, Cañasgordas, among others), where despite having great touristic potential, they have yet to identify local tourism sites that would allow them to plot routes or strategies so that tourism can contribute to the region’s social development.

In most of these municipalities, we see a lack of strategic planning in the tourism sector that would allow the heritage, historical, and cultural diversity of each village, since many of these have been dedicated to agricultural activity. However, there are all the same examples of some regions, such as Suroeste, where agricultural products, like coffee, have been used as part of the touristic charm, as we will see later. In conclusion, the municipal plans for all regions intend to plot an action plan based on tourism development as a new horizon that will contribute to improve the quality of life of their residents.

This finding is in accordance with the situation described by Manyoma-Ledesma & Barrios-Vargas (2011), and by Temizkan & Temizkan (2014), in which so-called developing countries, such as ours, the development of the tourism sector, though desirable, remains paltry. Fortunately, we find that municipal governments recognize the importance of tourism, thanks to the diversity of their own natural and cultural resources.

Development and revitalization of the regional economy with tourism

Tourism has been identified as an opportunity to bolster the local economy of various municipalities of Antioquia, and this much was clear in the development plans and the participants’ testimony. The generation of jobs through tourism opens new possibilities for the improvement of its residents’ quality of life, and this was visible in regions like Oriente, Suroeste, Occidente, and Urabá. For instance, in Oriente, the municipal plans for Alejandría, Concepción, San Rafael, Carmen del Viboral, San Luis, San Carlos, and San Vicente, positive contributions derived from tourism were identified, highlighting projection and action taking to organize the supply of tourism services, as an alternative for the generation of income, work for the populace, and therefore, revitalizing its economy. This lines up with Gambarota & Lorda (2017), who state that tourism is an option for local/regional endogenous development, where the abilities of local actors can be considered, and whose purpose is to improve individuals’ quality of life.

We find another example in the Suroeste region, where municipalities such as Montebello, Salgar, and Ciudad Bolívar, which are mainly characterized by their activity in the agricultural sector, have projects so that tourism becomes a source of jobs, coupled with agriculture. Likewise, in other municipalities in the Occidente region (Anzá, Heliconia, Abriaquí, Uramita, Dabeiba, and Olaya), which boast great landscape diversity, tourism has been little explored. Their governments mean to identify strategies that aid the sustainable exploitation of their touristic charm, with the goal of generating new sources of jobs and income. These strategies help nourish the tourism supply, and the companies offering complementary services, such as gastronomy, culture, hotel, and transportation services, partnering with the road development sector that seeks to increase the regional, national, and foreign tourists, creating a demand for goods and services. Yet another case is the Urabá region, with municipalities like Necoclí, Arboletes, Apartadó, Murindó, and Vigía del Fuerte; which have incredible geographical richness, diversity within the afro and indigenous population, with part of the region with access to the sea, which offers considerable opportunities to its residents for tourism development, and therefore, job and income generation. This is driving the upgrade of the current infrastructure of services, and the connection with other economic sectors.

Development of tourism based on the riches of the territory

Municipalities are clearly investing in developing a tourism agenda inspired by the territories’ natural and cultural diversity, linked to their productive dynamics. To that effect, in one of the interviews in the Orient region, a production sector participant said: “In the economic part of the region, we realize that we really need tourism to be able […] to expand, to be recognized as a region and such.” In the case of municipalities with substantial natural wealth- hydric, or biodiverse-, the aim is to develop ecotourism (Anorí, Caracolí, Belmira, Caicedo, Campamento, Liborina, Betania, Támesis, Murindó, La Estrella), or nature tourism (Puerto Triunfo, San Rafael, Sonsón, Alejandría), or adventure tourism (San Luis, Anorí, Frontino, Sonsón, Ciudad Bolívar, Támesis, San Pedro de Urabá), sports tourism (Sopetrán, El Peñol, Apartadó), agritourism (Caracolí, Anorí, Yolombó, Andes, Caicedo, El Retiro, San Pedro de Urabá), science tourism (Caracolí), ethnic tourism (Dabeiba, Mutatá, San Pedro de Urabá), or religious tourism (Girardota, San Pedro de los Milagros, Jericó, San Roque, Segovia, Frontino).

Medellín, as capital of the department, has had substantial growth on touristic level, especially in the last few years, with a considerable number of foreign visitors which have had a positive impact on the city’s economy. The development plan means to “boost the economic recovery of the tourism sector through tourism culture strategies, promotion of domestic tourism, brand generation, and acces to national and international markets (…) Contributing to Medellín’s recovery as a competitive tourism destination on a national and international scale, through strategies that promote the reinforcement of business, human resources qualification, adapting and improving tourism infrastructure, and intelligence processes that allow for decision-making in relation to connectivity, information, tourist experience and the positioning of the city as a tourist destination.

Even though some plans do not specify what kind of tourism is desired to be encouraged or strengthened, they do mention the hopes for the creation of routes or trails (coupled with the use of signs and other elements to help orientate tourists), taking advantage of the natural landscapes (Uramita, San Rafael. Tarazá), promotion of the region’s own agricultural products (Ciudad Bolívar and Betania, coffee-centered tourism), cultural attractions (Olaya, Alejandría, Carmen del Viboral, La Pintada, Envigado, Copacabana), or architectural heritage (Santafé de Antioquia, Jericó, La Estrella), or historical heritage (Buriticá, Envigado). On the other hand, some plans invest in sustainable tourism development, the preservation of territory resources, and the balance between different economic sectors. Consequently, the geographic, climatic, economic, social, historical, and cultural characteristics of most of the regions in Antioquia offer different possibilities for the stimulation of different kinds of alternative tourism than those traditionally advertised.

Tourism development promotion training

The levels of development in terms of tourism are different in each of Antioquia’s regions, due to, firstly, the clustering of initiatives in other economic sectors like agriculture, and secondly, to the installed infrastructure and capacity that the municipalities have for tourism activity. In this section we highlight the development of the residents’ capacity for provision of services, since it’s the fundamental aspect for bolstering the sector in all territories of Antioquia. In this sense, initiatives projected by the regions of Bajo Cauca, Oriente, Norte, Suroeste, Urabá, and Valle del Aburrá stand out. The project and indicators of these regions aim to strengthen the capacities of both tourism agents and community members that work as tourism operators.

Several development plans intend to implement training initiatives in order to promote tourism development: such is the case with Nechí, Santa Rosa de Osos, and Cocorná. The subject of training isn’t always specified, although the data are frequently associated with entrepreneurship program for the creation of touristic products (Briceño, San Andrés de Cuerquia, and Yarumal); education for the formalization of tourism service provisioning (San Luis), or training for customer service (San Juan de Urabá). Regarding this matter, a representative of the country’s most important job training institution emphasized that municipal governments approached them to contribute to tourism training topics, given the limelight of tourism in the development plans, and their importance to economic development. Nevertheless, this is a topic still not fully understood by the actors intervening in tourism (G.P. Personal communication, November 11th, 2020). One of the educational sector’s participants explained that there is a strong need to raise awareness and educate people about tourism topics and services, since the lack of preparation of those involved is evident.

In the same vein, another participant expressed, “we could also use help with training all our tourism line, merchants, restaurants, hotels, tourist guides; so let’s say […] we could prepare this whole population so it can welcome all the foreigners that come to our municipality, and for those foreigners, obviously, to feel welcomed, so they know they were served […] in a better way” (J.P., personal communication, November 4th, 2020). In general, the data showed that encouraging learning a second or foreign language is required for the provision of tourist ervices to non-Spanish speaking foreign visitors, a need already stated by the cited literature.

3.2 Potential for the development of foreign language skills, as a means of supporting tourism development

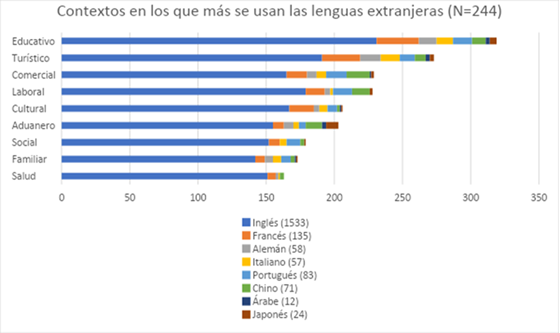

Since this study inspects the needs for the use of, and the contexts in which different foreign languages are used in the department of Antioquia, we find that a diverse set of languages cluster within Antioquia territory, besides the native creole languages pertaining to each of the indigenous communities that inhabit it. The survey’s data show that English is the most used language by people in the tourism sector in different territories within Antioquia; although the data show the existence of other languages such as French, German, Italian, Portuguese, Chinese, Arabic, and Japanese, English has a dominating presence in Antioquia’s context of tourism. (see Figure 2).

According to the survey’s data, the language with most uses throughout different contexts is English (1533), standing out in educational (231), tourism (191), and work-related (179) contexts. The second most used language is French (135), most distinctive in educational (31) and tourism (28) contexts.

The interest of municipal governments in community training in foreign languages is evident in their development plans. For example, several development plans (Cocorná, Marinilla, Angostura, Jardín, Ciudad Bolivar, Hispania, and Támesis) explicitly state the need for English education for boosting tourism. Among them, Cocorná’s municipal development plan indicates that “the municipality is very attractive to tourists, but we lack teachers or courses to promote English; this would be a bonus since it would attract even more tourists”. In Marinilla’s development plan, one of the defined actions is “Training in languages (English) of tourism service providers, as a possibility for internationalizing the municipality, and take advantage of the existing potential”; likewise, Angostura’s development plan, in the Norte region, expresses the need for tourist guides that know a second language.

Skills in a foreign language are related to the strengthening of tourism in regions of Antioquia, the territories thus acknowledge the importance of communicating with non-Spanish speaking visitors, which then results in good service for foreign visitors. Such is the case in the municipality of Jardín, which has an outstanding development in tourism; the sector’s enhancement is linked to its program Jardín Bilingüe, which aims to “establish alliances and/or agreements with institutions that offer English and customer service training for employees working at hotels, restaurants, bars, in the transportation sector (buses, taxis, motorcycle taxis), and other actors involved in the tourism sector”. Similarly, the municipality of Támesis acknowledges the importance of English in businesses, and in accessing international cooperation resources. Hence, the use of English as a language for transactions and interactions within the scope of tourism that may allow for bigger opportunities for economic development in the regions. With that in mind, a participant from the educational sector in Oriente (Sonsón) points out:

Being a touristic region and receiving a massive number of visitors from all over the world, it’s important to boost the educational and tourism sectors through these training services and programs. (E.C. personal communication, April 27th, 2020)

In addition, a government sector representative said that, given that their municipality is very touristic, foreign languages may be essential to “proffer information to other people that come from other countries, so for the municipality it’s a bonus, for the community as well” (P.A. personal communication, November 4th, 2020). Furthermore, a financial sector representative from Valle del Aburrá explained:

(…) They’re doing something so the experience in Medellín is absolutely different, from the tongue, the language, but also, since when the connection is already there, tons of things start happening, and that also applies to someone from around here speaking to people from other countries, (…) not just in English but in their own language (besides Spanish and English), so the connection is absolutely different. (D.O., personal communication, November 14th, 2020)

In the survey, several participants commented on the need for a second or foreign language to develop tourism: “training youth in rural tourism with a second language” (A.L. personal communication, April 27th, 2020); “training in ecotourism with a course in English” (E.G. personal communication, April 27th, 2020), etc. The survey and the focus groups with different actors of the production, educational, governmental, and civil society sectors alike confirmed the relevance of tourism for boosting the promotion of foreign languages, particularly English, and cultures for the regions, and its contribution to educational, cultural, social, and economic development within them.

Foreign languages, especially English, are associated with the opportunity to expand tourism, with “opening doors”, as participants from an educational sector focus group from Oriente mentioned. Education in a foreign language is brought up for youths, to help them get hired, as well as for adults that are tourism service providers, who, according to the participants, require at least basic education in the language. One of the participants from the Belmira explained that in their municipality, they sought to connect “the educational sector with the productive one”, using education in foreign languages, so as to offer visitors good service (J.P. personal communication, November 11th, 2020). They added that the development of foreign language skills is necessary: “...with that part, tourism would be much more practical, considering the people that are a part of it, most of them are older (…) So, then it would be a very, shall we say, practical project for them” (J.P. personal communication, November 11th, 2020).

The data collected during this research project revealed the undeniable connection between tourism and languages, especially in terms of education and training in a foreign or second language. In this assessment, we found that within different regions of Antioquia, there is a predominating need for learning a second language to strengthen the tourism sector of the populace, not just for tourist guides, as established by Law 2068 of 2020, the Tourism Law, but for the population in general as well, since there is an increasing number of individuals, families, and organizations that depend on, or see tourism as an economic opportunity.

As we mentioned in the beginning, our assessment focused on the identification of plurilingualism needs in the department of Antioquia. Although our purpose encompassed needs in relation to many different foreign and Colombian native and creole languages, general findings, and particularly tourism sector findings showed a distinct emphasis on the development of English communication skills.

This study’s findings show the increasing value of tourism due to its potential for the economic development of Antioquia’s regions, using its biodiversity, as well as its cultural, ethnic, agricultural, and architectural wealth of its municipalities. Consequently, municipal governments invest in developing or bolstering local capacities for tourism, adjusting for each territory's particular traits. Such an investment, to which a territorial approach can be attributed, seeks to shine a light on heritage, as well as the knowledge and history of the communities.

We found some correspondence between the findings of this study and the available literature on the topic: English commands communication, and, in general, tourism service provisioning (English no longer so much a foreign language as it is lingua franca, since it constitutes a form of communication with speakers that are not necessarily native).

Despite the data alluding to needs of other foreign languages in a diversity of contexts and sectors, it’s not commonly the case for the tourism sector, with French being the exception, which is mostly associated to the development of tourism in relation to cultural events. Additionally, despite the recognition of the cultural-ethnic heritage that some territories receive, possibilities of native languages being included as part of the process related to tourism services, like in signs, are not mentioned. Furthermore, consistent to what is reported in literature, the insufficient infrastructure and capacity installed in territories for the development of tourism, and lack of planning (either non-existent or out of date), resources, signs, community training, formalization of tourism services, and limited foreign language skills, which is the topic at hand. Hence the numerous development plans that propose bilingual Spanish-English projects for different population groups.

It’s surprising how translation and interpretation services were not identified as part of this reduced installed capacity, crucial as it is to boosting tourism. Most of the solutions center on education in other languages like English, ignoring the contributions of translation and interpretation to facilitating communication between speakers of different languages: in cultural and scientific events, translation of the content related to regional products, in financial transactions, and signs to aid visitors’ experience, and so forth.

4. Conclusions

From the results of this study, we find that making the territories’ richness the heart of tourism-strengthening strategy planning a valuable contribution. Therefore, making the most of local knowledge of the territory is essential to the implementation of tourism projects, so that it may equally empower all members of the community, who become ambassadors and even spokespeople for their territories. Doing so requires broadening the communities’ knowledge of their own territories.

Tourism constitutes in and of itself an opportunity to raise awareness of territories’ natural, cultural, and linguistic heritage. As such, language plays a vital role: the use of a widely used language, like English, facilitates interaction around a topic with visitors the world over. On the other hand, it serves as an opportunity to bring to attention to, and so preserving, the linguistic heritage that our indigenous languages are: for example, through signs and other components of a municipality’s linguistic landscape. Therefore, tourism-related initiatives must be accompanied by joint efforts of educational institutions, both at a secondary and tertiary levels of education, since skill development associated with tourism requires education in a diversity of topics; and in the case of languages, not just the development of communication skills, but other services like translation and interpretation as well. A defined and informed planning process based on the needs and potential of the resident population contributes actively to sustainable development, and to the improvement of a community’s quality of life. Additionally, the execution of integral language projects, in which content generated in other languages make it part of the linguistic landscape of municipalities, makes them indispensable for creating an environment that encourages an exploration of languages.

By virtue of this, we propose the development of not bilingualism projects, but of plurilingualism ones, so that the residents of territories are motivated to learn different languages, considering each territory’s vocation. Moreover, projects that motivate an exploration of native languages, especially the languages of communities living in the territory, as a political and social empowerment project around cultural and linguistic heritage.