In recent years, e-commerce has established itself as a suitable medium for its stakeholders to conduct their activities more efficiently, and its growth has contributed to the building of a well-functioning digital economy. Consumer spending greatly affects the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of a country, and migration to the digital trade environments has influenced these figures in the past years the most. The European Commission reported that consumer spending accounts for 56% of GDP (Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council on the functioning of the European ODR platform established under Regulation No 524/2013 (ODR for Consumer Disputes in 2019, hereinafter: the Commission Report). Therefore, its policy and actions aimed at creating policy incentives to smooth trade, such as the establishment of optimal DRSs, and reducing barriers for cross-border commerce, a preventive dispute method. The European Commission estimated that a properly structured DRS could save approximately 22.5 billion euros a year, which in the beginning of the past decade was 0.19% of the EU’s GDP (European Commission, 2012). Although the EU regulators have committed to enhance the internal and Single Digital Market (SDM) building DRSs, the model has left a trail of offenders, victims, and unintended consequences that have questioned the efficacy of their initiatives.

The paper revisits the problem of the uneven adoption and deployment of the use of ADR and ODR across the EU, and the lack of coupling ADR principles in ODR technologies due to overreliance on the technology itself, to the extent that ODR platforms have been said to be leapfrogging technologies in this field. ADR refers to any ‘out-ofcourt dispute resolution mechanism’ (refer to the Consultation Paper on the use of Alternative Dispute Resolution as a means to resolve disputes related to commercial transactions and practices in the European Union, 2011, available in the https://www.eumonitor.eu/, and see also: Hodges et al., 2012) while ODR is described as an “out-of-court solution to disputes arising from online transactions” (ODR Regulation EU No 524/2013).

The term coupling in use refers to the Luhmann’s social system theory meaning that defines it as developing an effective relationship between social systems and their environment that is the relationship between organization and interaction and between organization and society (Seidl and Mormann, 2015, p.4). It is stated that the ODR platform is a leapfrogging technology because it bypasses “some of the processes of accumulation of human capabilities and fixed investment in order to narrow the gaps in productivity and output (…)’’(Steinmueller, 2001). It can be argued that leapfrogging technology is not detrimental where fast development is needed and carefully planned, but regarding regional dispute resolution, fast tracking may turn into more of a deficit than an asset to the society. Likewise, ODR implementation and evolution have neglected the incorporation of dispute resolution advancements and the required coupling into a system that already considered essential to include certain ADR models.

This is a topical field of research because resolving consumer disputes outside of an adjudicatory setting through proper ODR mechanisms could effectively increase access to justice for consumers. In addition, enhancing customer service and productivity will enable economic development for the EU as a whole and the Member States individually. Furthermore, the effectiveness of DRSs must be continuously monitored and addressed; the European Commission reported on the functioning of the supranational ODR platform serious shortcomings (Commission Report, 2019): in 2019, 80% of the disputes submitted to the platform by consumers were closed after 30 days because the trader failed to issue a response. Also, in a negligible rate of 2% of the cases, the parties agreed on an ADR entity, allowing the platform to initiate the next step and transmit the dispute to the designated forum.

Estonia and the pre-Brexit United Kingdom are good examples to demonstrate the disparity that affects the harmonization of the ADR culture across the EU Member States, where the United Kingdom kept at the lead on ADR implementation. This paper speaks of ADR culture referring to communities that are aware, willing and competent on extrajudicial processes to solve and settle disputes and respect them along with the traditional adjudicative institutions. Estonia, among others, has been said to possess a much weaker ADR culture (Solarte-Vasquez, 2014). Some studies have addressed the efficacy of the DRSs proposals within the EU and denounced the uneven adoption and dissimilar development of the use of ADR and ODR capabilities in the region (Rule, 2002; Solarte-Vasquez, 2014; Cortes 2011; and, Page and Bonnyman, 2016), but in the absence of conclusive solutions, discussing the effectiveness of the ADR regulation in the EU and at the Member States levels is still justified.

The paper is divided as follows: the first section will present the theoretical background that helps explain the need to change the mode of governance within the landscape of ADR and ODR through effective coupling and outline the regulatory landscape. The second will examine the deployment and adoption of ADR and ODR in the EU to discuss the problem of insufficient redress and the possible solutions. The third and last will restate the need to build integrative models into AI-powered ODR and add some concluding remarks.

Theoretical Framework

The literature characterizes the contemporary ADR methods and procedures as more efficient and constructive to manage conflicts and to resolve disputes than the traditional schemes (Fiadjoe, 2004; Solarte-Vasquez, 2014; Cortes, 2017). ADR helps preserve relationships by helping the parties collaborate by reducing animosity and diminishing competitive incentives during its processes (Coltri, 2004). In part, what allows for a more satisfactory process in ADR is the conflict management expertise of professional negotiators and state of the art in the field of collaborative lawyering. In this context, if the conflict can be adequately managed, it should lead to constructive change, better relationships, and innovation, whereas, when conflicts are mismanaged, the results could have regrettable consequences, threatening relationships, systems, and institutions. It seems crucial for societies to develop an ADR culture that is based on integrative and collaborative processes and institutions that do not only settle disputes but aim at the peaceful and amicable resolution of conflicts. Integrative negotiation endorses “a more principled approach, even though the ultimate aim may also be to achieve the best outcome for each party’’ whereas the distributive kind is where the parties involved view the process as häving “limited resources for distribution, and the more one party receives, the less there will be for another.’’ The latter method resembles a settlement that is purely based on legal standards - one wins, the other looses. (In Brown,1999).

Negotiation, mediation, and arbitration are the best known of the ADR processes, and principled-integrative negotiation is one of the most popular approaches that can be used in their practice. The principled and integrative style of ADR is also claimed to foster procedural justice and fairness (Solarte-Vasquez and Hietanen-Kunwald, 2020) as the parties remain in control of the processes, play a more active role and decide on their own after reaching a sufficient understanding to create win-win solutions. It has been found that people are more satisfied with the outcome of a DRP when they think of it as legitimate (Vermunt and Törnblom, 1996). The theory on procedural justice refers to the fairness of processes by which a decision is reached, inspiring the practice of ADR, and mediation, especially (Rawls, 1999; Hollander-Blumoff and Tyler, 2011).

Mediation is one of the oldest and most popular forms of ADR, defined as assisted negotiation or a voluntary process that allows the parties to a dispute to resolve the disagreement directly, with the support of a neutral third party (Wall and Dunne, 2012; Lavi, 2016). Arbitration is a private, consensual, confidential dispute settlement method of private justice, where the third intervening party uses authoritative standards and has decision power. The alternatives to litigation have provided an avenue for resolving disputes amongst claimants efficiently and cost-effectively (Ponte and Cavenagh, 2005), and could release the courts of some of the burdens affecting the traditional system.

The theory of proportionality is also relevant to support the continuing development of ADR policies. According to Craig and De Burca. (2015), “an action shall not go beyond what is necessary to achieve the desired end; whether it was necessary to achieve the desired end; and whether the measure imposed a burden on the individual that was excessive concerning the objective sought to be achieved.” The traditional court system is unable to administer justice ‘of scale.´ Instead, ADR and ODR are suitable, provide the architecture and tools to handle disputes that arise online, and can be in charge of functions that judicial authorities can no longer manage, more proportionally.

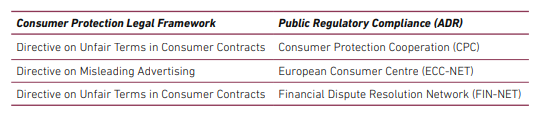

The EU has recognized and consciously aimed to incorporate forms of dispute resolution over the past 40 years throughout, as the objective is to “contribute to the proper functioning of the internal market and to ensure access to ‘simple, efficient, fast and low-cost’ ways of resolving disputes.” (European Law Institute Secretariat and the European Network of Councils for the Judiciary, 2018). Various recommendations, green papers, and secondary legislation were issued on the advanced use of ADR (i.e. Recommendation 98/257/CE; Communication 2001/161; Green Paper, 2002/0196 and Directive 2008/52/EC). Table 1 shows some examples of Regulation linking ADR and consumer protection.

Anticipating the growth of e-commerce, the EU made an effort to guarantee that the public can count on institutionalized means of settling disputes online. The preamble of the e-Commerce Directive shows that in sections 17, 51, and 54 (2000/31/EC), the necessity for national legislation not to hinder the progress of ADR but amend legislation where applicable to capitalize on ADR benefits, considering that the conflicts, which may arise from e-commerce interactions, are characterized by their rapidity and scope. However, years away from the adoption of the Mediation Directive (2008/52/EC), which is concerned with civil and commercial disputes, the EU has not expanded on this or any other specific method. The law should have led to an increase of ADR awareness and adoption, but the advancement and use of ADR processes have met difficulties at the community level. The Directive 2013/11, and the Regulation 524/2013 are the other two main instruments that relate to dispute resolution for the proper functioning of the internal and SDM. The Regulation on the ODR platform, allows consumers and traders to select an appropriate ADR body to resolve e-commerce conflict (Page and Bonnyman, 2016). It has to be said that the implementation of ODR was not intended at first to be an augmentation of ADR but to fulfil the gaps for consumer disputes generated by the increase in cross border exchange following the expansion of the digital markets (represented by e-commerce indicators such as client retention rate, profit margin, and related interactions, for instance).

The Regulation of ODR has failed to include the principles of ADR, although it could have been an augmentation of ADR. However, according to Katsh and Rabinovich-Einy (2017), ODR did not emerge with the intent to affect ADR processes. In the EU, the policymakers promoted a medium for increased efficiency and access/availability to resolve disputes online. While the process and concept of ODR can undeniably offer significant progress but the vision was too modest, and the gap that leapfrogging technologies leaves in the transition from ADR to ODR has interrupted progress in the DRSs field. The extrajudicial systems online should also offer proper redress and resolution and take into account procedural fairness in the administration of disputes. Banerjee and Annuar (1999) pointed out that ODR was a radical advancement and claimed that it disregarded people’s cultural and social needs (Banerjee and Annuar, 1999). As Poblet noted in the book Mobile Technologies for Conflict Management, “[t] echnlogy does not transform conflict per se: humans do, and the question is which, when, and how technologies may facilitate their quest” (Poblet, 2011). It is pertinent for policymakers, national laws, private sectors to prompt changes of the DRSs to incorporate social developments and human centredness to promote the fair redress of disputes, using any medium. As Solarte-Vasquez (2020) has indicated, nothing justifies abandoning the pre-digital advancements of ADR and its approach to strategies, styles, and services, as well as the standards drafted for offline dispute resolution (Kaufmann-Kohler, and Schultz, 2004). In sum, ADR should have a symbiotic relationship with ODR to become an effective DRS.

ODR can fall into two main categories: the sui generis form of dispute resolution, and the Online Alternative Dispute Resolution (OADR) kind (Kaufmann-Kohler and Schultz, 2004). The first uses the tools offered by the internet and machines, such as automation; this form neglects the origins of ADR may implement it to stand alone with limited human interaction (Leigh and Fowlie, 2014). In contrast, OADR connects to the capacities that have been developed in ADR, hence, it is easy to argue for OADR, because, like Solarte-Vasquez (2014) has claimed, online mechanisms would be the most friendly and effective when designed to meet the standards of advanced offline DRSs. The rest of the paper is based on this understanding of OADR, and considers chief not merely the respect for objective procedural justice standards, but also for subjective procedural justice, by following guidelines which will help remove mistrust on the technologies and processes, and facilitate proper dispute resolution and redress.

From ADR to ODR and back

The development of an ADR culture within the EU has witnessed some advancement towards led by supranational organizations, but a regression in the implementation at the Member States level when given the responsibility to develop the extrajudicial system substantially and organically. The following outline of these processes shows that the timing has clearly overlapped between establishing special ADR rules for consumer matters and general ADR and ODR rules for cross-border disputes. The Commission’s initial reveal of the strategic use of ADR was exemplified in the form of Recommendations in 1998 and 2001 that laid down the core principles of transparency, impartiality, and effectiveness. During the timeframe, the problem was about lack of access to redress inside and across the EU borders.

Moreover, the Commission introduced various instruments to encourage the use of ADR schemes as a more convenient and flexible to resolve disputes. In 2002, the system advanced through the launch of the Commission’s Green Paper on ADR; in 2004, the Voluntary European Code of Conduct for Mediators and 2007 Regulation on European Small Claims Procedure. Subsequently, the Directive 2008/52/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 May 2008 on certain aspects of mediation in civil and commercial matters (the Mediation Directive) was launched (Storskrubb, 2016).

During the transposition of the Mediation Directive, another wave of legislation was brewing, which caused a shift from the development of the core concepts of ADR competences within the EU Member States towards the development of consumer redress across the EU borders due to the increase of transactions via e-commerce. According to the European Commission, „more than half of complaints (56.3%) received by the ECC-Net were linked to e-commerce transactions, out of which less than 9% could be referred to an ADR scheme in another Member State” (European Commission Executive Summary of the Impact Assessment, 2011). Thus, the ADR Directive 2013/11 and ODR Regulation, issued a couple of years after, seems more far-reaching as it requires the Member States to guarantee consumers have access to ADR schemes (Storskrubb, 2016). Consumer protection is a priority but not the only field of application of ADR, and also a shared competence between the EU and its Member States, according if to give to the articles 169 (1) and 169 (2) (a) of the TFEU and extensive interpretation. However, it appears the essential features of an ADR scheme are left exclusively up to the Member States, which resulted in the proliferation of ADR bodies and lack of unity. The detriment of advancing the scheme too rapidly is evident in (1) The adoption challenges of the use of ADR, which kept those methods underdeveloped and (2) The ODR platform being unready due to the ADR situation in the EU.

A Directive does not resolve its adoption challenges, and it is unreasonable to believe that expanding from national borders to regional jurisdictions will guarantee a substantial automatic change in the sector of out of court dispute resolution. ADR culture varies significantly in the EU, with some countries lingering behind the adoption, awareness, and commitment to self-regulation and ADR competences (Solarte-Vasquez, 2014). Countries such as Estonia, Romania, Lithuania, Latvia, Slovenia, and Slovakia, if to consider what has been reported, did not gain as much as expected by just passing the legislation on mediation, conciliation and formally developing the legal framework for ADR and ODR schemes.

Estonia, geographically an Eastern European country, falls under the groups of countries with faster compliance but lowest ADR adoption rates. The slow progress of adopting an ADR culture before, during, and after the implementation of supranational legislation and the low interest to go beyond the minimum requirements to advance the sector has been prevalent. “Although there are many alternatives to traditional litigation and court proceedings now available, civil disputes in Estonia are still mainly settled by the courts” (Madden, 2012). The literature further emphasizes that negotiation and arbitration are rarely utilized in Estonia, and one of the primary factors is due to the extended period when there was no knowledge about these techniques or law regulating mediation. Another instance of lack of acquaintance is the implementation of The Estonian Conciliation Act that followed the Mediation Directive that captioned mediation as “conciliation,” which, technically speaking, is a different ADR methodology. This may have possibly posed additional adoption challenges when deciding on the acceptable use of mediation and other DRSs (Joamets and Solarte-Vasquez, 2019).

In contrast, the United Kingdom went far beyond the scope of the Directive. The Government introduced a paper for solving disputes in the courts that endorses automatic referrals towards mediation in small claims matters. It should be noted that this is as a common law jurisdiction, with a well-developed and influential ADR culture where traders’ membership is compulsory in several economic sectors characterized by a more effective use of ADR to resolve consumer disputes, namely in: energy, financial services, and higher education (Cortes, 2017).

Unlike Estonia, the UK reports significant awareness and adoption indicators. Already in 2009, the Financial Ombudsman service administered 160,000 cases; this reflects preparedness of the DRS to adapt, and the pre-existence of a local ADR culture, at least to the degree that responded to the government regulatory efforts. These actions show that the state is truly committed to the institutionalization of a broad spectrum of dispute resolution methods (Solarte-Vasquez, 2014). England and Wales, in particular, have witnessed cases where the traditional court system has encouraged ADR procedures as a more proportionate measure to resolve certain disputes. An illustration of this endorsement by the law transpired in the observations expressed by the judge presiding over the case Egan vs. Motor Services (Bath) Ltd Egan v Motor Services (Bath) Ltd [2007] EWCA Civ 1002, where the claimants needlessly spent a disproportionate amount of money in legal fees throughout the proceedings. The building of a European ADR culture is still in its beginnings. Ponte and Cavenagh (2005) have stated that the ADR and ODR framework are still “underused and have yet to reach its full potential”. After three and half years of the launch of the ODR platform, ADR is not a mandatory feature in the design of the platform nor the administrators have been given instructions on the procedural aspects of how the implementation be better executed. The intention is for ADR schemes to resolve disputes online, but the provisions on how to carry out these functions are exempted from the legislation.

The major underlying concern is that the institutionalization of online DRS has been a hurried process. In spite of the significant increase in computational power, the development of the technology has not advanced on procedural justice, human centeredness, and legitimacy; new mechanisms are in place, but there is no data on the access to effective redress or justice. Again, ODR can do little to solve the challenges of trade an exchange on its own. Nevertheless, the EU has continued to take initiatives, based on the former Agenda 2020, to put technology to the service of the public and to promote a fair, open, and secure digital environment. The Commission built the SDM Strategy on three pillars: providing better access for consumers and businesses to digital goods and services, creating the right conditions for digital networks and services to flourish, and maximizing the growth potential of the digital economy. The new digital agenda 2025 extends from the previous one and promises to focus on an even stronger digital Europe. In this context, the DRS that will support the economy must align technology and social development involving the core concepts of ADR not to continue hindering their full potential. As Luhmann indicated, “no system can fulfil another system’s function, but every system relies on the problem-solving capacity of all the other systems fulfilling their functions” (in Görke & Scholl, 2006 p. 647). Hence, continued work on ADR competences is required. The incorporation of constructive, integrative, and responsive ADR methodologies may continue to be slower than the implementation of technical solutions because the sui generis type of dispute resolution dilutes the relational components that are essential in conflict management during human exchange interactions.

Katsh and Rabinovich-Einy (2017) also allude to the optimism of ODR through digitalization, where a large number of disputes can be processed with the use of algorithms. ODR acting as the “fourth party” exploits the intelligence of machines, can remove the need for synchronous communication and a dispute expert in the process of consumer redress (Katsh and Rabinovich-Einy, 2017). The ODR platform showed the dynamics of this technology where the first year of implementation, 1.9 million people visited the platform, and around 24,000 complaints were submitted (Commission Report 2019). During the second year of implementation, there was an increase of visitors on the platform, with five million people visiting the platform. Moreover, there was an indication of 50% in complaints in 2017 (European Commission, the functioning of the European ODR Platform Statistics 2nd year 2018). Concerning geographic distribution in the first year of ODR operation, consumers generated the majority of complaints in Germany and the United Kingdom., once again demonstrating where the ADR culture is more influential, which in general may correlate to consumers’ empowerment to seek redress. One-third of the complaints concerned a cross border dispute. Within the second year, records showed similarly, that the highest complaints by consumers were from the same countries with an influential ADR culture. The reply rate by traders has been poor and is a reflection of the perception towards the use of ADR. (Commission Report, 2019) The first year of implementation of the ODR platform showed an exorbitant amount of 85% of complaints closed automatically before being solved by an ADR body (Commission Report, 2017). A survey conducted with consumers whose cases were closed automatically reported that 40% were settled directly with the traders. Furthermore, only 1% of disputes reached an ADR body (Commission Report 2019). A “dispute resolution process that fails 60 percent of the time is far worse than a tool of communication that is beneficial to the parties in only 40 percent of the cases” (Kaufmann-Kohler and Schultz, 2004, p. 20). It is essential to note that settlement does not refer to an ADR process, as no records can show there was adherence to the due process or prove the consumer was dispensed justice.

Synchronous communication requires instantaneous responses during a dispute resolution process, which is usually achieved face to face; however, the same effect can be produced online through digitalization with the use of instant messaging through chat boxes, forums, and video conferencing that smooth communication. Features of synchronous communication such as instant messaging, video conferencing should be incorporated to the complaint and dispute handling processes, reviewed by dispute resolution experts. Mediators that resort to online communication (chats) had higher successful win-win results as opposed to the ones who had other types of interactions. Online negotiations that integrated ‘small talk’ were four times more likely to lead to a settlement (Poblet, 2007). The current procedure of the EU ODR platform is reliant on the nature of asynchronous communication. This timeframe, on the other hand, may help disputants temper emotions before the ADR process starts. The mediator should engage with the consumer and trader once the conflict is made public via individual and or cooperate caucusing. This process will facilitate the fulfilment of procedural justice, and fairness standards because the claimants will have a voice, and the legitimacy of the process, trustworthiness, and respect will give them access to justice (Solarte Vasquez and Hietanen-Kunwald, 2020). It has to be considered that ODR may sometimes be the suitable and only method available to resolve a dispute that is low in value and would be disproportionate to adjudicate.

Highly bureaucratic DRSs would further propel shortcomings for individuals to receive access to justice, particularly in countries of low exposure to the integrative and principles ADR culture. However, ODR should go beyond providing a contact point for disputants that seek proper redress. ODR schemes fall into either a first-generation or second-generation kind where the former incorporates the tools of technology, and the latter merges AI into the landscape; unfortunately, it is apparent that the EU has not maximized the ADR capacity of even the first generation ODR. In conclusion, the coupling of ADR methodologies into the ODR platform innovatively and proactively is key to enhance dispute resolution processes and to implement procedural justice principles, increment the rates of redress, and the participation of the community in better practices, for the system to become more symbiotic and have an impact on the wellbeing of the society in general.

ODR and other technologies for dispute resolution in the EU

It has become evident that to be more careful in the planning and implementation of AI-based ODR is imperative, notwithstanding the importance of technology for dispute resolution. The way it may facilitate redress opportunities and access to justice are well established.

AI operations simulate, do not fully imitate human intelligence (Lodder and Zeleznikow, 2012). Even though advanced systems could already function on their own, the deployed technologies in the legal field require human intervention. If a DRS combines the expert capabilities of humans with computational power, the chances that it would result in a system that could be able to handle dispute resolution efficiently and effectively are higher. As emphasized, ADR takes into consideration procedural justice and fairness and it is upon these same merits that the European Commission issued the principles for the development of AI in the EU (European Commission, 2020). AI is developing fast, and it should continue to promote human centredness and wellbeing, this goes hand in hand with transparency and responsibility for building trust and improving the secure use of AI, and is fully in line with the existing regulatory framework. The approach is already present in the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in its article 14th (Regulation (EU) 2016/679). AI systems must be excellent and trustworthy (European Commission, 2020 p.3) and people’s trust is affected by the understanding of the computational processes for decision making that involve the use of their personal data.

To close the gap between computational power and human interactions and overcome the problem of inadequate redress (for a dispute resolution ecosystem of trust), the integrative models of ADR need to be built into the ODR platforms. Incorporating these ‘social’ technologies into the pan European ODR platform would strengthen the centralized model; algorithmic development would be assisted by dispute resolution experts and could aim at eliminating the disparities where the ADR culture was not mature, or where adoption challenges have been said to occur. The effectiveness of the process calls for a developed substantive design by default methodology to foster effective digital and mediated communication. The parties should be encouraged to exchange information, improve their perception of the dispute resolution, and recognize their options and alternatives to the negotiated agreements, while the system could nudge the parties (Guihot et al., 2017) or provide a systematic guide on how to agree on what may be an acceptable outcome. The core of the dispute resolution process relies on the mediatized technique that is utilized to allow disputants to arrive at a settlement agreement. Therefore, one of the most suitable techniques proposed is the rule-based system; this is the simplest form of building AI systems that allows the possibility to include human expertise from a particular field (Carneiro et al., 2012). The procedure is based upon IF-THEN logical structures, where each rule derives stored knowledge by experts within the given area to enhance the technology, in this case, the ODR process (Carneiro et al., 2012 p.13). In addition to this method, are other strategies in which subfields of AI technology are closely connected to conflict management where emphasis is placed on combining the principles of ADR captioning skillsets used in negotiation, such as managing emotions within the scope of an intelligent environment through Ambient Intelligence (Carneiro et al., 2012). The main gain would result from developing ADR such as mediation and negotiation algorithms that can identify changes in the parties in real-time and readapt strategies that will reflect in the interaction process and produce mutually beneficial outcomes (Carneiro et al., 2012).

The United Nations has envisioned the need to promote and develop redress in cross border trade precisely in the e-commerce environment (Cortes, 2017). Similarly, to the EU legislation, the rules it has proposed seem to refer more to the resolution of low value but high volume disputes in e-commerce but inclusive of both Consumer-to-Business disputes and Business-to-Business disputes.

Concluding remarks

The paper assessed the institutional evolution of ADR and ODR in the EU, focusing on its regulatory framework and some of its pressing shortcomings. It restated and developed arguments that are discussed in the literature but not in policy making about DRSs in the region. The problems of the uneven ADR capacities and capabilities in Member States and the low adoption rates, understood as successful utilization of ADR/ODR methodologies were revisited, highlighting the deficient integration of the pre-digital and the digital technologies for conflict management and dispute resolution. It was suggested that they are exacerbated by the low attention to the preparedness of the public regarding ADR and the unarticulated and unsystematic leapfrogging of ODR and other technologies for dispute resolution that is taking place as a result.

The paper presented Estonia and the United Kingdom as salient examples of the ADR landscape in Europe. It was showed that there is a prevalent culture by the Government and private bodies that encourages mediation as a better form of dispute resolution in the latter, in contrast to the situation in Estonia. It helped explained that the legislation does not create a culture and poses no particular challenges. With this understood, it should be easier to communicate that to proceed to the implementation of ADR in the platform of ODR must take into account non-legal strategies.

The paper coincided with the arguments categorizing ODR as a leapfrogging technology, because it innovates radically, while dismissing fundamental components of the processes that are affected. Online-based dispute resolution tools that do not follow the core principles of ADR may be efficient and scalable, but have little significance for effective conflict management. The short timeframe between the Regulation and the launch of the European ODR platform is a limitation observed in the DRS evolution of the region. The deployment itself may not seem rushed, but it was done without analysing its structure from the point of view of its capacity to handle disputes on their substance. The technology has helped a considerable number of consumers to convey disputes online, but the potential of the digital environment to enhance the European DRSs is unexploited. The EU platform operates solely as a site to generate complaints, while the intention was to be a medium and support their resolution when arising from or during the use of some technology. It has become apparent that the more advanced ADR features it incorporates, the more effective it will be, but adjustments should not be made before completing the groundwork effort of improving the European ADR culture. The challenges of ODR to increase access to justice, legitimacy and trust are especially difficult to address and operationalized, because procedural justice and fairness are not clearly demarcated concepts.

Moreover, AI, as a developing area of technology, is being inaugurated into ODR as the next step in the ‘advancement’ of DRSs that could champion the management of disputes. The Member States and supranational entities are embracing digital AI in making processes more efficient, accessible, reliable, secure, and effective, but the interest in collaboration, procedural justice, and fairness should not be forgotten. The EU has recently set the incorporation of principles of transparency and legitimacy into the design of AI as a priority for building trust and excellence, and it is in this manner that it continues to be a pioneer in the field of consumer redress. In order to enable an authentic paradigm shift in the way disputes are handled beyond the traditional court systems, ODR should be conceived as an augmentation of ADR, and the two should be strategically and more systematically coupled.