1. MIGRATION, GLOBAL EMERGENCY, AND THE (RE)INVENTION OF THE ENEMY

According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 5.4 million Venezuelans have fled their country since 2014, mainly due to severe shortages of medicine, medical supplies, and food; a ruthless government crackdown, which has led to thousands of arbitrary arrests, hundreds of prosecutions of civilians by military court, and torture against detainees; extremely high rates of violent crime; and hyperinflation ("Venezuela's Humanitarian Crisis..." 5). The countries that have received the largest numbers of Venezuelans are Colombia, Peru, Ecuador, Chile, Argentina, and the United States. Only Colombia is sheltering an estimated 1.8 million Venezuelans. The actual number is likely to be much higher because there are more than 270 unofficial crossings along the border. According to a Colombian government report ("Gobierno expide..."), there are 911,714 Venezuelans living in Colombia without legal permission, enduring the precarious conditions of the unemployed or informally employed, which is a considerable segment of the population in the country, where official figures indicate that unemployment has reached a historic 16.8%, and where almost half of the working population in 23 of the nation's major cities have informal jobs. That is equivalent to over 5 million Colombians. Amidst this social crisis, Venezuelans living in Colombia have to endure the stigma of being perceived as a burden to the already dire national economy.

The current coronavirus health crisis has only aggravated this state of affairs. As a result of the toll that the pandemic has taken on the already decimated job market in Colombia, thousands of Venezuelans decided to return to their home country, which proved to be an even more trying ordeal than leaving it, as the Venezuelan government limited their entry and, upon arrival, treated them as "bioterrorists," as president Nicolás Maduro has explicitly referred to the returnees. According to a New York Times report, the government's public health strategy included urging citizens to report people who had returned, holding the returnees in poorly equipped containment centers, and detaining and intimidating physicians and experts who questioned Maduro's policies (Kurmanaev et al.). Despite the unwillingness of their government to deal with this migration crisis amidst a colossal global health emergency, thousands of Venezuelans endured the difficulties of returning to their home country only to realize that the conditions were even more dreadful there than in Colombia.

The simultaneous occurrence of a migration crisis and a global health emergency on the Venezuela-Colombia border highlights in an especially compelling way the need to recognize the body as an essential component of contemporary migration. As thousands of Venezuelan immigrants cross the border from one country to the other-and back-, public officials in both countries take measures to prevent the spread of COViD-19 within their territories. The body of the immigrant is therefore overtly perceived and publicly represented as a dangerous source of contagion, which brings to mind the idea-explored by Antonio Negri and Michael Hardt-that contagion is a "constant and present danger, the dark underside of the civilizing mission" (135). Although this idea is explored by Negri and Hardt as part of their analysis and critique of imperial power, the way in which the Venezuelan exodus is perceived in Colombia attests to the dominance of the anxiety of contagion in the collective imaginary. In fact, the approach proposed by Negri and Hardt already envisioned this anxiety as an essential component of the post-colonial and globalized human experience, as the following passage demonstrates:

The contemporary processes of globalization have torn down many of the boundaries of the colonial world. Along with the common celebrations of the unbounded flows in our new global village, one can still sense also an anxiety about increased contact and a certain nostalgia for colonialist hygiene. The dark side of the consciousness of globalization is the fear of contagion. (136).

Although the COViD-19 pandemic has bluntly revealed the validity of this statement, human flows between Venezuela and Colombia throughout the last decade have increasingly become-even before the pandemic-a source of anxiety for the Colombian population, whose perception of security has deteriorated in tandem with the aggravation of the Venezuelan crisis. This state of affairs brings to mind the following question posed by Homi Bhabha: "How do strategies of representation or empowerment come to be formulated in the competing claims of communities where, despite shared histories of deprivation and discrimination, the exchange of values, meanings, and priorities may not always be collaborative and dialogical, but may be profoundly antagonistic, conflictual and even incommensurable?" (2). The relationship between Colombians and Venezuelans is especially conflictual in the sense explored by Bhabha because it is imbued with deep-rooted political prejudices. Being the only country in the region where the left has never held power (which explains in part the prolonged guerilla warfare that has defined its recent history), Colombia is represented by its political elite as a stable haven where socialism cannot prosper1. The way in which the Venezuelan migration crisis is rooted in the collective imaginary calls for alternative representations that transcend ideological binaries to focus instead on human experiences of displacement and uprooting. These alternative representations would necessarily oppose the mass-mediatic approach that has informed the general view about this ongoing crisis. Resistance to the regimes of representation that dominate the current debate about the Venezuelan exodus can be attested in artworks like Beatriz González's Zulia, Zulia, Zulia (see Fig. 1), a 50x195 cm oil on canvas that depicts the plight of hundreds of thousands of anonymous immigrants who cross into the northeastern region of Zulia on the Venezuela-Colombia border. Through this pictorial approach to a migration crisis that has taken center stage in the last decade, González explores the relationship between politics and aesthetics in times of emergency while unveiling the aporias of nationality and belonging in contemporary Latin America.

González's pictorial exploration of the crisis on the Venezuela-Colombia border is paradigmatic of the artistic ethos that has defined her status as one of the most prominent Latin American contemporary artists. Born in Bucaramanga in 1938, González studied Art at the Universidad de los Andes, where she was influenced by renowned figures like Marta Traba and Juan Antonio Roda. She positioned herself as one of the leading artists of her generation with Los suicidas del Sisga (1965), an oil on canvas based on a press image of two lovers who committed suicide in the Sisga dam. At that early stage of her career, the artist was particularly interested in the formal aspect of the press image itself. In her own words: "No fue la historia, ni el tema, ni las anécdotas lo que me entusiasmó, sino la gráfica del periódico. Aparecen las imágenes planas, casi sin sombra. ... Estas imágenes se adaptaban y corroboraban la idea que yo venía desarrollando en pintura: aquella de que el espacio puede lograrse con figuras planas y recortadas" (Ponce de León 16). González's pictorial reinterpretation of press images that were paradigmatic of sensationalist journalism was consistent with a trend in Colombian art that led to multiple aesthetic reappropriations of both high-brow and popular culture references. As Halim Badawi points out: "Gran parte de los artistas colombianos más avezados, modernos o contemporáneos . se apropiaron de las tradiciones cultas y populares, como ocurrió, ya en la década de los setenta, con Antonio Caro (1950), Beatriz González (1938) o Álvaro Barrios (1945)" (105).

Although González's artistic interests have undergone several transformations throughout her career that spans over five decades of uninterrupted production, the artist is still interested in exploring the process of rearticulating through painting what has been previously documented by the mass media. Being aware of the fact that-as Walter Benjamin argues in "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction"-art cannot remain unaltered after the advent of photography, González does not abandon painting, but rather explores the possibility offered by this artistic form to comment on press images that are already part of the collective imaginary. This can be fully attested in Zulia, Zulia, Zulia, which is based on press photographs of undocumented Colombians crossing the border with their belongings because they were afraid of losing them after being deported by Venezuelan authorities. Significantly enough, González's point of departure to explore the humanitarian crisis along the border and beyond is not the experience of the Venezuelans themselves-as Teresa Margolles choses to do in Estorbo-, but that of Colombians living in Venezuela and being forced to abandon their country of residence.

This fully reveals the aporias of nationality and belonging amidst an unprecedented regional emergency. The images of undocumented Colombians carrying refrigerators, TV sets, and beds through the Táchira river-which connects the city of San Antonio de Táchira in Venezuela with the small town of La Parada in Colombia-reveal the fragility and ultimate unreliability of national identity when it comes to the human ordeal entailed by displacement, insofar as the bodies that experience this ordeal are not defined by their national origin, but rather by their common human frailty.

Although this may lead to the temptation to pity immigrants-a temptation against which Slavoj Zizek has recently rebelled in his book Refugees, Terror and Other Troubles with the Neighbors-, González's painting problematizes this approach by highlighting the unparalleled human resilience that is condensed in the painting's symbolical vindication of strength-both physical and psychological-that is at the core of the experience of migration. González's pictorial approach to the silhouettes of migrant bodies leads to the creation of a pathos image, which Pérez Oramas has defined as a pictorial representation whose meaning is not solely based on its documentary value, but also-and mainly-on the message of human pathos that it conveys (120).

González's exploration of this pathos through a pictorial reinterpretation of press images depicting the migration crisis on the Venezuela-Colombia border underscores a commitment to delve into connections between politics and aesthetics, which has been an essential element in the artist's career since the 1980s. This is fully attested in pieces like Decoración de interiores (1981), a silkscreen printed on a 140-meter curtain in which González articulates a sardonic critique of former president Julio César Turbay Ayala (1978-1982) based on a press image-published by El Tiempo-that features the president partying with his friends and ministers amidst a national crisis of unprecedented state violence and human rights violations. For González, this image was the epitome of the degradation of the political elite in Colombia: "Turbay es, para nosotros los colombianos, un personaje de una reconocida inmoralidad, un político de la peor clase. En ese momento no pensé en el aspecto moral, sino en lo bueno que sería ser un pintor de la Corte, como Goya o Velásquez" (Ponce de León 15).

After the Palace of Justice siege in 1985, González's sardonic approach to the political gave way to a more sober pictorial exploration of current events. In her own words: "El humor se perdió hace rato. El humor crítico se perdió con el Palacio de Justicia" (¿Por qué llora si ya reí? 1:54). For the first time in her career, the artist began to overtly conceive her work as political in a more traditional sense: "Decidí ser una artista política porque pensé que los artistas no podíamos permanecer callados frente a una situación semejante. Fue una toma de posición deliberada" (Laverde Toscano 119). Despite this transformation, the artist continued to explore critical possibilities derived from the reinterpretation of graphic references that have not received the attention they deserve from spectators who have been numbed by the continual bombardment of news and information.

As María Margarita Malagón-Kurka has pointed out, the mediatic coverage of current events has been detrimental to the spectator's empathy and sensibility towards reality, which has led Colombian artists like González to resist this deterioration of public sensibility through their work. This resistance became especially relevant in the 1980s and 1990s in Colombia, when overexposure to violence was pervasive. In Malagón-Kurka's words: "La sobreabundancia de imágenes erosionaba la eficiencia comunicativa de los medios y en especial su habilidad para conmover a los espectadores emocionalmente" (39). González explicitly referred to this in a 1977 interview with Marta Traba, in which she stated that the social role of the artist should be "ver a su alrededor y no incorporarse, con una mansedumbre que espanta, a lo que llega por todos los medios de comunicación" (Traba, Los muebles de Beatriz González 64).

This commitment takes central stage in Zulia, Zulia, Zulia, insofar as the painting offers an alternative approach to a crisis that seems to be worn out from excessive media exposure. Amidst the tense political climate derived from this crisis, it comes as no surprise that Colombian mainstream media, which is a paradigmatic example of what Louis Althusser (in On the Reproduction of Capitalism) would categorize as an ideological state apparatus, reproduces and magnifies the notion that even if life in Colombia is not perfect, at least it is not as bad as in Venezuela. This self-congratulating approach to the Venezuelan exodus aims to exploit a foreign crisis as a means to conceal political emergencies that are unbecoming for the current administration-like the systematic assassination of social leaders, which has intensified since Duque's election-and to create consensus around the undesirability of an alternative political agenda in Colombia.

This nationalistic approach to a local migration crisis and to the global pandemic in which it is framed brings to the forefront the idea-first explored by Carl Schmitt in The Concept of the Political and later revisited and contested by Chantal Mouffe in On the Political-that "the specific political distinction is that between friend and enemy" (Schmitt 26). According to Mouffe, "the friend/enemy distinction can be considered as merely one of the possible forms of expression of the antagonistic dimension which is constitutive of the political" (16), which allows for the articulation of what she considers to be a challenge for democratic politics, namely, to try to establish the we/they relation in a different way. The rhetoric of both the Colombian and Venezuelan governments is consistent with this conception of the political, which highlights the need to establish an external enemy as the sine qua non condition for internal national cohesion.

Zulia, Zulia, Zulia contests and challenges this approach to the political by problem-atizing the very existence of what Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe have categorized as "a radical outside, without a common measure with the inside" (18), which is the cornerstone of identity constitution from the point of view of the friend/enemy dichotomy. The color palette used by González leads to a pictorial representation of the border as a wholly imaginary barrier, blurring thus the we/they dichotomy. This aspect of the painting evokes Pamela Ballinger's approach to migration as a phenomenon that is liminal by definition, insofar as it is marked by the experience of being "betwixt and between home and host country" (16). González brings to the forefront the liminality of this experience in an especially compelling way by focusing on the impossibility of visually segregating the two territories that constitute home and host country. As the title of the painting suggests, these territories are depicted as a landscape marked by indistinguishability and repetition, as if Zulia constituted a constellation of human experiences that transcend geographical barriers. To understand this, we need to delve into the symbolic undertones that resonate with the name "Zulia."

Once the heart of Venezuela's energy industry, which was worldly known for its opulent oil wealth, the region of Zulia has suffered in a particularly harsh way the consequences of the failed economic policies of the last decades. In the past, Zulians regarded themselves as inhabitants of the "Venezuelan Texas." Oil workers used to fly by private jet to the Dutch Caribbean territory of Curacao to gamble their earnings in casinos. Maracaibo, the capital of the region and Venezuela's second largest city, was the first town in the country to be lit by electricity. Fueled by wealthy donors, Maracaibo hosted three symphony orchestras and the largest museum of contemporary art in South America. Today, it is the epicenter of the economic and social collapse that ensued after the fall of oil prices in 2013, which was worsened by mismanagement and corruption. As a result of this crisis, 700,000 people-which is a third of the metropolitan population-have abandoned the city in only 3 years. Eveling Trejo de Rosales, Maracaibo's former mayor, has recently referred to the city as a zombie state, where those who are left are "dead men walking" (Faiola).

Zulia is therefore a paradigmatic instance of the Venezuelan crisis. As such, it also stands as a symbol of the experience of migration and displacement that is at the core of González's pictorial approach to this crisis. The centrality of repetition in this approach-as evinced in the painting's title, its visual patterns, and its elongated format-highlights the possibility offered by painting to provide an iconographic synthesis to key contemporary events that are covered by newspapers but are then easily forgotten. In that sense, seriality and repetition have become for González a pictorial strategy to fight collective amnesia derived from constant, virtually uninterrupted access to information in contemporary societies-as explored by Andreas Huyssen in Twilight Memories-and to promote reflection around images that circulate widely. In an interview with César Rojas Ángel, the artist states that "al reiterar una imagen de la prensa, al partir de la reportería gráfica, y hacer no solamente un cuadrito al óleo, sino volverla papel de colgadura, volverla lápidas, volverla una cantidad de cosas, eso obliga a una reflexión" ("Beatriz González: repetir..."). This idea is the keystone of González's ethical approach to aesthetics, which is based on the notion that art plays a fundamental role in the prevention of oblivion, as will be explored in the next section.

2. THE MEMORY OF THE IMAGE

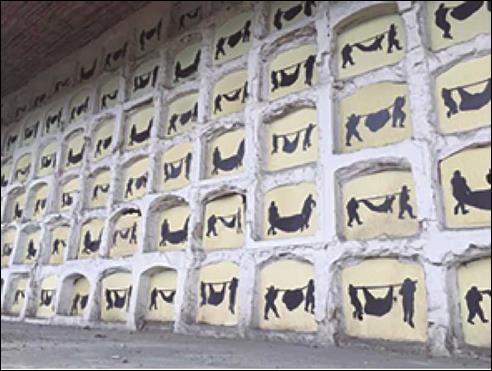

González's depiction of the human ordeal caused by the Venezuelan crisis is reminiscent of her aesthetic approach to victims of violence in Colombia, as can be attested in works like Auras anónimas (see Fig. 2), an installation for collective grieving inaugurated by the artist in 2009 at the Central Cemetery of Bogotá. For that work, González occupied nearly 9,000 niches of the cemetery's mausoleums with panels of human figures carrying corpses. The paintings are based on press photographs that show members of the military using bags and hammocks to carry corpses found in a mass grave in Northeastern Medellín. As Ana María Reyes has poignantly observed, "among all of González post-1985 paintings of loss and bereavement, no other work compares to this installation in terms of solemnity" (226).

This solemnity is key to understand the work from its very conception. The figures in Auras anónimas are based on González's Vistahermosa series, a set of drawings inspired by press photographs showing members of the Colombian Armed Forces carrying corpses after military attacks or after uncovering mass graves. The reiteration of those images in national newspapers led the artist to a glimpse that was central to the conception of the work, namely, that-as she herself expresses it in a piece for El Espectador-"a diferencia del siglo xix, en el que los cargueros llevaban a los viajeros por nuestros territorios, en el siglo xxi se llevan muertos en distintos soportes: plástico, telas de lona y hamacas" (González).2

Both Auras anónimas and Zulia, Zulia, Zulia stem from González's exploration of the possibility offered by painting to transform press images into iconic images. This exploration entails an approach to the relationship between image, history, and memory that echoes Susan Sontag's idea that "what is called collective memory is not a remembering but a stipulating: that this is important, that this is the story about how it happened, with the pictures that lock the story in our minds" (86). It is worth noting that Sontag considers images as the only material vehicle that can mobilize this stipulation. Inspired by an analogous intuition, González explores, on the one hand, the formal simplification of the image-to the point that the figures become no more than black silhouettes traversing the space-and, on the other hand, the serial repetition of the resulting iconic images. This pictorial method of iconographic stipulation triggers an affective response that facilitates the fixation of these images in the viewer's memory.

In the case of Zulia, Zulia, Zulia, the painting's seriality also suggests that the experience of migration captured in the press images that inspired the work is only one instance of an ongoing humanitarian crisis that has manifested itself in multiple ways throughout the last decades. González's pictorial strategy consists in transforming this particular visual instance into an image whose symbolic universality transcends the specificity of individual experience and hints instead at the collective resonances of that experience. For the artist, the ultimate symbol of this collective ordeal is condensed in the image of human silhouettes carrying their belongings, which are an essential part of who they are. The artist explores this symbol extensively in her pictorial approach to displacement in Colombia, as can be attested in works like Inundados (Flooded) and La carguera (The Carrier), which are based on press images of Colombian families who have been forced to abandon their homes due to floods. The pervasiveness of this symbol in González's pictorial approach to migration suggests that all individual stories of displacement are collectively interwoven around the fundamental experience of carrying belongings from one place to another. Although at first sight this may seem a truism, González's exploration of that insight powerfully humanizes migration by emphasizing its most elementary feature.

This artistic approach to the topos of the wandering body entails an ethics of witnessing that asserts the power of the pictorial image to symbolically safeguard in the blink of an eye (Benjamin, "Theses" 262) a constellation of human experiences linked to migration and displacement in contemporary Latin America. Through the pictorial reinvention of existing images, or-as the artist herself has referred to her method- through the commitment to articulate a representation of a representation (Traba, Diez preguntas 4), González suggests that her work is not that of an ethnographer, but that of a secondary witness who approaches migration from a distance that is both physical and critical. It also suggests that this position of secondary witness grants the artist an interpretative freedom that leads to the articulation of a form of collective memory that would conceive the pictorial image as a privileged cultural device to capture history from a non-historiographical stance.

This approach leads to an implicit critique of the dangers of ideological patronage that Hal Foster has identified as the inevitable risk that the artist-ethnographer must face (173). Furthermore, the distance that González takes from ethnographic approaches to migration leads to an implicit criticism of the claim of some artists and intellectuals to become spokesmen for the experience of victims of social and political injustice. Doris Salcedo, for instance, has made this claim explicit through a rather abstract statement that conveys, nevertheless, her messianic conception not only of art, but also-and perhaps mainly-of the artist. According to Salcedo, contemporary art is "un juego esquizofrénico en el que el centro del otro se coloca en mi centro y yo miro al otro desde mi centro y mi centro se coloca en el centro del otro y me miro desde afuera" (146).

In contrast to this schizophrenic notion of artistic production, González privileges the pictorial exploration of her own perspective as an artist, without ever losing sight of the fact that as a secondary witness her center cannot be put into the center of the other. In recognizing subjectivity-her own-as a fundamental trait of her pictorial approach to migration, González questions the capacity of the artist to intervene in a direct, unmedi-ated way in the reality captured by the artwork. This skeptical approach to the relationship between art and activism is explicitly articulated by the artist in an interview with Arcadia, in which she states that art cannot overthrow political regimes ("Yo no creo...").

However, this does not lead to a conception of art as an impotent cultural device. For González, art has the power to capture history in a unique, potentially transgressive way. In the case of the human ordeal ignited by the Venezuelan crisis, the artist implicitly rejects the ideological regimes of representation that serve the interests of one party or the other in the political and symbolic struggle embodied by the Colombian government and its counterpart in Caracas. By privileging the human features of migration and displacement over the ideological component that has taken center stage in today's mass-mediatic coverage of the Venezuelan exodus, González vindicates the power of art to foster a collective reflection about the present, which transcends journalistic and political prejudices. As the artist herself has pointed out in connection with her latest retrospective at the Reina Sofía Museum in Madrid, she is interested in exploring "imprecise images." This sheds light on the importance of ambiguity in her artistic project, which is grounded in the idea that the work of art has an unparalleled capacity to update constellations of meaning that promote dissensus (Rancière) by activating in the viewer affective associations that are essentially unpredictable. As the next and final section seeks to show, this approach entails an ethical stance that sheds light on the artistic challenges posed by the depiction of contemporary events amidst unprecedented local and global crises.

3. THE POLITICS OF PAINTING IN TIMES OF EMERGENCY

The political power intrinsic to the symbolic act of incorporating press images of the Venezuelan exodus into a pictorial tradition that will survive those images opens important questions about the responsibility of the artist towards contemporary history. González's approach to this responsibility is based on the idea that, amidst the urgency of current events, the ethical demand that art ought to respond to would not consist in the reduction of the artwork to an instrument of social and political engineering. Rather, González's ethical stance towards the relationship between politics and aesthetics is based on the exploration of the power of the pictorial image to safeguard and symbolically recognize a constellation of human experiences that deserve a place in our collective memory.

This approach reiterates the centrality of memory in contemporary artistic and cultural manifestations worldwide. As Andreas Huyssen has pointed out, the proliferation of memory museums and other commemorative monuments is an unmistakable symptom of the contemporary Zeitgeist, marked, especially since the 1980s, by an accelerated proliferation of discourses on memory, particularly around the Holocaust. This has resulted in what Huyssen calls a "culture of memory" (Present Pasts 12), whose global tentacles are supported by a robust culture industry, which sustains a very lucrative memory market. Thus, González's interest in depicting the Venezuelan migration crisis as a sociopolitical emergency that deserves to be reiterated and remembered is part of a global trend in which memory functions as a symbolic magnet that brings together a diverse array of cultural manifestations linked by a commitment towards remembrance as a powerful political weapon.

Nevertheless, González participates in this commitment in a way that challenges the tendency to romanticize memory, insofar as she incorporates to her artwork images that have been previously reproduced by the mass media, which suggests that memory in contemporary industrial societies cannot be perceived as a pure, unpolluted realm, segregated from the influence of the mass-mediatic image. In other words, what is exceptional about Zulia, Zulia, Zulia is the relationship that the work explores between migration as a key component of human experience in contemporary Latin America and the representation of this phenomenon within a culture that sees and interprets its own contemporary history through the lenses of mass media. If, as Pierre Nora has argued, the kind of memory that depended on the intimacy of a collective inheritance has been replaced by mass-mediatic and ephemeral images of current events (8), González does not try to retrieve an archaic form of memory but opts instead for a deliberate act of reinventing images that have been massively reproduced and consumed.

Nevertheless, as can be attested in Zulia, Zulia, Zulia, the artist's approach to the testimonial function of press images is ambiguous: on the one hand, she is aware that this function has been overshadowed by the intrinsic dynamics that govern the transmission of information in contemporary societies, which reduce all images to a status of pure immediacy and transience, thence foreclosing all possibilities of an afterlife of the image. On the other hand, however, she recognizes the importance of press images for articulating an archeology of the present. This dialectic approach sheds light on her exploration of the troublesome relationship between artistic production and the sense not only of immediateness, but also of emergency that the mass-mediatic reproduction of current events entails.

González has recently made this relationship explicit in her installation Cinta amarilla (Yellow Tape), which is currently being displayed at the Casas Riegner gallery in Bogotá. The work consists of a set of yellow tape rolls (like those used in construction and road-repair projects) in which the artist imprinted the human silhouettes of Auras anónimas. As González has recently expressed it in an interview with Cristina Esguerra, "cuando empezamos a hacer la obra, nunca sospechamos lo que iba a pasar en el país. Colombia siempre está en peligro, pero ahora está participando en uno mundial" (Esguerra Miranda). This statement serves as a reminder of González's overt awareness of the fact that she is an artist painting in times of emergency. As such, she is conscious of her role as witness to a troubled present.

This awareness, however, has not derailed the artist from her interest in the purely formal component of her work. As she puts it in the aforementioned interview: "Hay una cosa que me parece significativa: cómo en mi proceso todo se fue convirtiendo en siluetas. Por un proceso mental, las figuras se fueron simplificando de una manera extraordinaria. Me encanté con las siluetas... Se han vuelto importantes en mi trabajo" (Esguerra Miranda). This statement brings to the forefront the problem of the relationship between form and content in the work of art, rethought by Hal Foster in terms of an opposition between aesthetic quality and political relevance (172). An analysis solely attentive to the latter leads, as Hilton Kramer has observed, to a functional blindness towards the properly formal problem of aesthetic quality and, therefore, to the reduction of the work of art to an epiphenomenon of the historical process (88). According to Kramer, avoiding this reduction should be one of the essential tasks of a critique that is sensitive to the specificity of artistic language, that is, to the irreducibility of the artwork to a political message.

González herself is aware of this irreducibility, as can be attested in the following statement: "No soy una artista política ni una pintora comprometida a la manera en que lo son los muralistas mexicanos. El artista se compromete con la realidad en el momento en que tiene la voluntad de sentir que su obra puede servir como una reflexión histórica. ... El arte cuenta lo que la historia no puede contar" (Espejo). González's interest in exploring the iconic power of silhouettes in works like Auras anónimas, Zulia, Zulia, Zulia, and Cinta amarilla suggests that, when it comes to depicting contemporary history, the task of painting in times of emergency entails the realization that art has the power not only to say what history cannot say, but also to warn about present and future dangers. The artist's approach to the relationship between art, history, and the ethics of witnessing is therefore grounded in the principle that the pictorial image must be a matter of concern not only for the past, but also for the present and the future, which is evocative of Benjamin's idea that "every image of the past that is not recognized by the present as one of its own concerns threatens to disappear irretrievably" ("Theses" 247). González's commitment to symbolically safeguard iconic images of current events consolidates an artistic ethos based on the conviction that, although art cannot overthrow political regimes, it certainly can reiterate what should not be forgotten