1. INTRODUCTION1

"Breathe: A Ghost Story" (2018) is a short story written by Kate Pullinger and published within the Ambient Literature Project, a collaboration between UWE Bristol, Bath Spa University, and the University of Birmingham, which started in 2016 and lasted for two years. A smartphone narrative, accessible through the web browser of any smartphone with internet connection, "Breathe" uses readers' data and metadata (location, time, weather, camera, accelerometer movements) and incorporates them into the narrative itself, making thus each reader's experience of the story different depending on their own specific situated interactions.

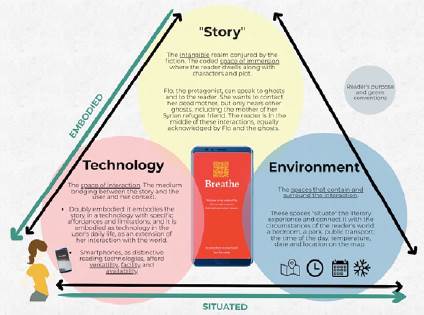

This paper makes use of the metaphor of triangulation-a geometrical concept applied in GPS cartography for locating a point or an object in space-to identify and analyze the space in which literary interaction with "Breathe" takes place. It aims to locate its reading experience in the correlations of three interdependent spaces: (1) story, (2) technology, and (3) environment. The central argument of this proposition is that the correlation of these three spaces "triangulates" the literary experience of "Breathe" which allows understanding how the text can be performed and experienced by real people in real-life circumstances.

This argument builds on the presupposition that literature does not happen nor is experienced in a vacuum between a text and a reader, but rather in everyday situations that involve concrete purposes, technologies, audiences, and environments. The two frames for this analysis are ambient literature (Dovey, Farman, Dovey et al.), a "genre" based on the links between the text and the context of its readers (the fusion of the reader's situational data with "data" of a literary piece through mobile technologies), and M-reading (Kuzmicová et al., Maloney), the increasing use of mobile phones to read fiction, which affords users new and specific ways of engaging with texts. In the end, the triangulation metaphor used in this paper not only implies a mere relation of spaces in connection to a literary event, but it is proposed as a methodology to locate and analyze literary experiences in connection to real-life situations, which can in turn help us approach the question of how embodied technologies and situated experiences determine our literary interactions.

The principal characteristic of "Breathe" as ambient literature is the use of conditional text: "text that alters in response to data that is pulled into the story via APIs [application programming interfaces]" (Pullinger, "Breathe and Conditional Text" 1). In other words, "Breathe" uses data about the weather, time, and location of the reader, in combination with the camera, accelerometer, and touch screen ofher mobile phone to create a story that changes according to her specific circumstances each time. As Pullinger explains: "Each API has several variations. For example, while location can provide street or city names, it can also include places, i.e., 'nearest café' or 'nearest train station.' The time API can pull in the time in numbers or words, i.e., 'night,' or season, i.e., 'winter,' while the weather API alters the text in relation to the temperature wherever the reader might be" ("Breathe and Conditional Text" 3). This means that the story actually consists of many stories, each one of them co-created by a certain combination of variables that are, in principle, virtually infinite and "only the most dedicated reader, who returns to the story in multiple locations around the world, whatever the weather, over the course of an entire year, will experience all the story's potential permutations" (2).

This is as well the principle defining all ambient literature: a literary co-creation between what happens in a story and what happens in a reader's particular set of spatio-temporal circumstances. This "fusion of data" between the story and the world is mediated by a particular technology, with a set of affordances, that is "embodied" (and performed) by a particular user at a particular time. Ambient literature, then, is not a combination of defined places in literature, technology, and locations, but a flux of movement that is always changing, as Jonathan Dovey, one of the scholars involved in the Ambient Literature Project, explains:

All the systems that produce the encounter are dynamic: the city scene, the technological assemblage, the human subject-all these are always in flux. ... The experience is fleeting, contingent on the changing mise-en-scène. Whereas representational art forms have offered us an experience of stasis, events captured in time forever (and therefore out of time), the experiences at hand here put the reader/listener into time, we become as parts of the flow and change of the dynamic systems. (151).

While this can be applied in principle to any kind of literary interaction, it becomes especially relevant in the case of ambient literature as an explicit case of technology and situation pur-posedly co-creating a dynamic literary piece (and a literary experience).

Understanding all the components of this dynamic system as spatial and interde-pendent-the story, the technology in interaction/the body using it, and the situational context-can therefore provide a unified frame to analyze the use of literature in real-life conditions: interactions between the three triangulated spaces produce what can be understood as a comprehensive real-life literary space, which aligns with the spatial considerations that Michel de Certeau proposed in his foundational book The Practice of Everyday Life:

A space exists when one takes into consideration vectors of direction, velocities, and time variables. Thus space is composed of intersections of mobile elements. It is in a sense actuated by the ensemble of movements deployed within it. Space occurs as the effect produced by the operations that orient it, situate it, temporalize it, and make it function in a polyvalent unity of conflictual programs or contractual proximities. (117).

According to this reading, a real-life literary space would necessarily need to consider the different, mobile, and interrelated elements of its interaction/enaction. Literary space-and space in general-is thus understood in this paper not as a fixed container to be filled with elements, but following Doreen Massey's conceptualization, as the product of interrelations (presupposed by the existence of interacting pluralities) in permanent construction, configuration, and reconfiguration (9). In essence, space is the result of the movement of plural elements interacting with each other, in constant, perpetual change.

In the context of this paper's proposition, this begs the question of why to take interest in locating an interaction through a triangulation metaphor. If space is the result of movement and change, would locating a specific interaction space not constitute a contradiction in itself, an act of fixing the essentially movable? The key to answering this question lies in not trying to equate triangulation/location with the act of fixing an interaction in space and time. Rather, triangulating a literary interaction means here identifying the moving parts of the literary space and understanding how they might connect to one another at a given moment, to subsequently change and reconfigure them. Triangulating means making sense of the movement of plural literary interactions as they happen in real life, instead of fixing them in generalized, artificial scenarios. It means trying to find-codified in the "where" (in the relations of interrelated plural elements)-the "why's" and "how's" of real-life movable literary interactions: why a person would choose to read a certain content, on a specific medium, at a particular time, and not another; how such person would enact said interaction, and then choose to do differently when one or several of those variables change.

Mobile technologies have an immense role to play in this movable literary scenario today, especially when taking into account, on the one hand, how their pervasiveness has the strength to move literature out of certain traditional spaces of use, to make it always available at hand and on the move; and, on the other, how mobile technologies have become the predominant medium of interaction with text in recent years and most likely will continue to be so in a hybrid system of intertwined physical and digital interactions. As it turns out, "the world of bits did not do away with the need for physical mobility; instead, smartphones show that the spaces we move through and the digital information we interact with have merged" (Frith 132).

In an article published in the Wall Street Journal in 2015, Jennifer Maloney called this phenomenon of text consumption in mobile devices "the rise of phone reading." Using comprehensive data by global information firm Nielsen, Apple, and other sources, Maloney concluded that phone reading is already becoming a dominant technological practice in literature use: " What has captured publishers' attention is the increase in the number of people reading on their phones. In a Nielsen survey of 2,000 people this past December [2014], about 54% of e-book buyers said they used smartphones to read their books at least some of the time. That's up from 24% in 2012, according to a separate study commissioned by Nielsen" (6-7). And similarly: "Some 45% of iBooks purchases are now downloaded onto iPhones. ... Before that, only 28% were downloaded onto phones, with most of the remainder downloaded onto iPads and a small percentage onto computers" (Maloney 14). In the end, these literary spatial considerations, and the triangulations resulting from them, address the question of what the place of literature in everyday life is, for what purposes it is used, by whom, and how it affects the worlds that people inhabit while using it. As Rouncefield and Tolmie conclude in a study about reading in the twenty-first century home:

We need to appreciate the different processes and kinds of reading (reading for pleasure, reading as work, reading as a distraction or time-filler, etc.), the different circumstances in which reading is accomplished as well as the 'technologies' of reading and the interactions between them. With regard to the different technologies of reading, computer screen, e-book, magazine or book, we need to bear in mind some of the very different 'affordances' of these technologies and how they therefore fit into everyday living. (133).

The following sections correspond to each space of the triangulation metaphor, every one of them correlating with the other two and, in a way, containing (and being contained in) the others.

2. STORY: THE VIRTUAL SPACE OF IMMERSION

Let us come back now to this paper's study case and to the literary world to the creation of which readers and their circumstances contribute with the mediation of a smart-phone. "Breathe" is the story of Flo, a woman who can speak to ghosts. In her room, Flo is looking to contact her deceased mother, but only gets the interference of other ghosts who contact her and eventually contact the reader. In the meantime, Flo tells you, the reader, her story, and the story of her Syrian refugee colleague who lost his mother back in Syria. As the story unfolds, Flo's narration creates links with the reader's particular environment, like a childhood memory based on a particular weather, that is, the weather at the reader's location at the moment of reading. At the same time, the ghosts haunting Flo start to haunt the reader as well, locating her in the particular space where she is, observing her from a nearby coffee or train station (variable according to the reader's location). There is one ghost in particular who tries to reach Flo, a ghost who lost her child. In the end, the story concludes with the realization-both Flo's and the reader's-that the ghost looking for her child is not Flo's mother, but the mother of her Syrian friend; and Flo, her story, and the reader are the mediums for her to find him.

This is the story, the intangible realm conjured by fiction that readers enter while leaving their own world behind. While the story lasts, readers inhabit that world along with the characters and their circumstances; and when the story ends, they are sent back to their own life in their space separated from fiction. This is how literary immersion would normally be understood. However, in the specific case of "Breathe," entering the virtual story does not presuppose leaving the reader's own world. Quite contrarily, to be able to dwell in Flo's world, the world of the reader must enter the story, at the same time that the virtual story must come out to the real world of the reader. The story only works as long as this game of correspondences can take place. As Jason Farman explains in "Stories, Spaces, and Bodies": "The virtual is thus not a simulation but is something that exists in an important dialogic relationship with the material world" (107). Therefore, the intratextual space is no longer only virtual, and it is not limited to the borders of the text. Immersion into the virtual space is an immersion into the literary, as well as an awareness and immersion into the reader's own surroundings.

There is a vital component of genre in this dialogic interrelation between virtual and real spaces. Genres themselves are common spaces within a more or less conventional set of practices. To some extent they share certain types of literary characters, with certain types of actions, and are read by a community of people sharing a type of purpose to be fulfilled in the act of reading within those genre parameters. In the case of "Breathe," the genre of this "ghost story" can be located to a certain extent between fantasy and horror, and its reader would expect to have an experience that more or less corresponds to the parameters of those genres. In "Does it matter where you read?" Aneèka Kuzmicová states:

Narrative genres tapping more directly into basic affects, e.g., thrillers or horror stories, may thus depend on mental imagery to a higher degree. For instance, imagine reading The Shining by Stephen King, the famous horror novel set in a hotel in the Rockies, and being just a stone's throw away from a mountain resort. Most likely you do not need to be able to see the resort, or give it an articulate thought as you read, for its proximity to inform your level of horror via environmentally propped mental imagery. (15).

These "basic affects" create a connection between the world of the story and the world of the reader. In "Breathe," an uncanny atmosphere inside the narrative is mirrored and translated into an uncanny experience of the world we inhabit while reading. The purpose is to feel the haunting experience as one feeling inside both worlds at the same time. One can safely say that humans experience fictional horror in situated ways. For example, audiences tend to react differently to a horror film if they are in a dark, empty movie theater than in a well-lit room with friends or family. It is an entirely different feeling to read a horror novel in a park at night than to do it in daylight. Along with what Kuzmicová states, it can be argued that certain genres are more prone to environmental propping than others, and that there are certain settings in which this enactment of feeling horror through fiction is more ideal for that purpose than others.

In "Breathe" Flo is alone in her room being haunted by ghosts. If it is presumable that one of the environmental conventions of horror fiction can be reading in one's bed at night, then an environmental connection can be established. The story creates and enhances such possible connections between the room in Flo's world and the room in the reader's world. For example, at the beginning of the story: "/It's early/. Around me, the city /wakes/ [variable: time of the reader]. The space I'm in couldn't be more familiar: four walls, window, door, bed. The silvery grey duvet I've had since I was small. The purple velvet pillow my father gave to me" (Pullinger, "Breathe" 2). And then, after revealing the existence of ghosts that are watching Flo and the reader: "It's /morning/ where you are [variable: time of the reader]. Around you, /Bogotá/ rises [variable: reader's location]. I'm glad I've found you. I'll tell you my stories" (5). And then one of the ghosts: "Stupid stories. Stupid girl. I'm close by. I'm on [variable: street close to reader's location] already. You need me-not her" (6).

In Why Horror Seduces, Mathias Clasen points to the environments that can be perceived as horror atmospheres in an evolutionary and culturally formed manner. The evolutionary response to horror is fear, something humans, among other animals, have formed as an advantage in an evolutionary process, and at the same time, horror is in some ways culturally determined (1):

Horror fiction typically is designed to draw us in and keep us engaged. It does so by drawing up a recognizable fictional universe (the setting tends to be fairly naturalistic even in stories that feature supernatural monsters); giving us an "anchor" in the fictional world (one or more characters from whose perspective we experience story events and/or with whom we can empathize); and exposing that anchor to nasty events. This structure allows for audience transportation, that is, it allows audiences to project themselves into the fictional world and feel with and for the protagonists. (30).

In this way, readers can relate to fictional horror through recognition, and they can feel what the characters are feeling by empathetically putting themselves in their place:

We need to learn what to be afraid of, but such learning takes place within a biologically constrained possibility space. While different environments feature different threats, some threats have been evolutionarily persistent enough, and serious enough, to have left an imprint on our genome as prepared fears, as potentialities that may be activated during an individual's life in response to personal or vicarious experience, or culturally transmitted information. (Clasen 39).

Thus, the virtual space in "Breathe" is not an ethereal realm of imagination readers dwell in because they left their own world; they can inhabit that realm only by bringing their own world with them. In horror fiction, this is a somehow conventional awareness. As Carolyn R. Miller explains, genres can be classified according to semantics, syntactics, and pragmatics (152). That is, they can be determined by content, form, and use (what uses people give to them in the world). In the horror genre, readers get aesthetic pleasure from feeling fear in their own circumstances through fiction (Clasen 29). That is the purpose pursued by the horror fiction itself and by readers who interact with the genre. In "Breathe," both purposes are met and satisfied when the world of fiction and the world of who is using it fuse together to become one.

Thus, the literary experience in "Breathe" acts like a mirror, one of the paradigmatic heterotopic spaces of both "here" and "there" that Michel Foucault described in "Of Other Spaces." In the mirror, the "here" becomes another world inside the reflection, and the world reflected back is both our world and "another" world:

In the mirror, I see myself there where I am not, in an unreal, virtual space that opens up behind the surface; I am over there, there where I am not, a sort of shadow that gives my own visibility to myself, that enables me to see myself there where I am absent. ... Starting from this gaze that is, as it were, directed toward me, from the ground of this virtual space that is on the other side of the glass, I come back toward myself; I begin again to direct my eyes toward myself and to reconstitute myself there where I am. The mirror functions as a heterotopia in this respect: it makes this place that I occupy at the moment when I look at myself in the glass at once absolutely real, connected with all the space that surrounds it, and absolutely unreal, since in order to be perceived it has to pass through this virtual point which is over there. (4).

In "Breathe," the first "page" of the story is a mirrored image of the reader and her surroundings, allowed by the front camera of the phone. Superposed on that image of ourselves, on the face of the reader, is the text: "Welcome to the world of Flo. She can talk to ghosts. And she knows where you are" (0).

It is in this way, for the triangulation metaphor, that the real is contained in the virtual as much as the virtual is contained in the real. The reader of "Breathe" and her surroundings are an active part of the story in the same way that the story takes place within her world (the reader's) and her surroundings. The content depends on the situational space, and the link between those two is the technological space, for, since the story does not happen in a vacuum, a medium is needed to incarnate it and to converge the two worlds into one.

3. TECHNOLOGY: THE EMBODIED SPACE OF INTERACTION

The virtual world of "Breathe" is physically manifested on a mobile phone's screen, coded into text that is displayed in an interface where users can read, write, touch, and interact, a machine with lights, cameras, accelerometers, sound, GPS, etc. At the same time, the story, manifested in this technological tool, exists in a human hand, attached to a human body like an extension of its capabilities: a body that takes the machine along everywhere, every time, and uses it as a medium to interact with the world. In "Breathe," in the opening mirrored image of the reader on the first page of the story, there are yet two more lines of text at the bottom of the screen: "Is your phone in your hand?" And then a clickable answer: "Yes. I'm ready" (0).

Jason Farman talks about changes in computing in the last two decades, from static desktop stations to computing power always available at hand, and the changes that this interaction produced in the ways we perceive and deal with the world. It has been: "A paradigm shift in how computing gets practised. ... In this shift from personal to pervasive computing, practices of access to digital information are no longer tethered to a desktop but instead are with us wherever we go. This allows us access to the internet and to engage in other computing practices that once required going to a location specific for computing (e.g., the desk at the office or home)" (102). This pervasive "embodiment" of computing technology implies a change in how the mind interacts with the world, and how knowledge comes to be and gets to be practiced through bodies and technologies. Embodiment is itself a flexible concept, displayed with different approaches in a spectrum of diverse disciplines, from philosophy to psychology and from cognitive sciences to neurosciences and human-computer interaction. From Heidegger to Husserl, and to Artificial Intelligence today, embodiment ideas defy a cartesian separation of body and mind and embrace instead an interrelatedness between mind, body, and experience. In their review of embodiment across disciplines, in a frame of digital technologies, Farr et al. explain that "the separation of the body from mental abstraction is a problem, and many theorists argue that the two (body and mental abstraction) are not separate but part of a unified experience. This reunification of body, action, and mind is a key consideration in contemporary debates around embodiment" (3).

Within this general starting point, one could think of the technological space of interaction (the smartphone) as an embodied space of interrelation between the virtual literary realm and the real world. In this regard, the virtual space of "Breathe" would act as doubly embodied: on the one hand, as the story embodied in the machine, and, on the other, as the machine (with the story inside) embodied in the human user (the reader) and her particular ways of using a tool to interact with the world (or worlds, if we take into account that the literary and the physical are contained in each other).

"Breathe" is embodied in the mobile phone to an extent that the phone itself- and the possibilities it affords-is an active part of the essence of the story. Without the touchscreen, cameras, accelerometer, and locative actions facilitated by the GPS inside the phone, "Breathe" could simply not be the variable, interactive story that it is: a form of ambient literature. Beyond location, weather, and time, it is the programming of an interactive interface what affords the story to enact its ghostly features. The accelerometer, for example, allows for a layered textual organization in which changing the angle of the phone reveals a certain ghost's message. The touchscreen allows for the finger to unearth different messages underneath the text of the page. The animated screen allows for a sort of radio static effect that gives the illusion of interference, and for the ghosts to undo the text to reveal their messages, to "hack" the story and create their own. The camera projects the space of the reader onto the space of the text. In this regard, it can be said that "Breathe" is as much the written story as it is the written code for the programming to be displayed on the phone. Extensively, "Breathe" is as much the story as it is its technology.

Matt Hayler points to a similar direction when analyzing "the importance of embodiment in understanding the nature of technology and its effects (an embodiment not just of the user, but also of the artefact deployed)" (19). In his book Challenging the Phenomena of Technology, he proposes the existence of an object independent from human perception, and a set of real affordances of the object itself, which are afterwards put into use by human agents: "Affordances, therefore, aren't the same as the perceptual aspect of a thing (which may or may not be accurate), but are instead, rather, real properties of the object that exist only in relation to their being actionable in use. A codex, for example, affords reading whether or not someone is there to read it, but readability isn't a physical property of an object independent of a reader" (145). This is the point where the story embodied in a technology connects with the technology embodied in human use and interaction. After all, it is in use when technology can deploy its affordances, and that use is performed by a human agent with a body, with a set of agencies and with specific purposes in time and space. The embodied technology of the mobile phone offers a pervasive extension of human capabilities like memory, vision, listening, and temporal and spatial perception. For example, users can traverse the world through Google Maps before or during their physical movements through actual space; people can go to other places and "know" spaces in which they are not physically present. The mobile phone becomes in this way a part of the human body, like glasses would to a person with limited vision or an artificial prothesis for someone with a missing limb. It is in this Heideggerian fashion that Farr et al. present the "transparency" of a technology like the mobile phone:

For example, we can become so entrenched in activity with a particular tool (e.g., a pen when writing) that we often forget its existence. In this way it is seen to become 'embodied', to become part of you as a 'master' of that the tool. This has particular relevance today for thinking about embodiment in the context of ubiquitous digital technologies .... The properties of these technologies are considered to enable interaction with them to occur through everyday action and activity with the world, thus offering a 'seamless' connection between the digital and the physical. (4).

It is indeed in everyday action that people interact with phones as technologies and forget about their existence, so much that they only realize them when no longer have them at hand or when their batteries are dead. In those cases, the lack of a mobile phone can become a sort of missing limb. These are the tools where literary reading is happening, and where "Breathe" presents itself to the reader to be used in relation to their world. Phones are companions, and there is an important affective factor in how people rely on them to interpret the world around them. This means

[t]he possibility that a digital device, whether it is a desktop computer or a mobile phone, can have a generally positive affective value that plays into one's user experience regardless of the specific type of activity performed on the device, reading included. For example, research in the media and communication field shows that mobile phones in particular tend to be invested with strong affections whose overall value is positive .... In several studies, users have reported stable and highly individuated positive feelings for their mobile phone in its capacity as a personalized, indispensable and irreplaceable companion. (Kuzmicová et al. 337).

The embodied existence of "Breathe," in the phone and in users, can exist as a companion, as does reading literature on a phone: a machine that is dear to the point to which people can feel vulnerable if they do not have it around. The affordances of the technology become affordances of use to the extent that users do use technologies, and use them continuously, every day in their everyday life. In "m-reading: Fiction Reading from Mobile Phones," Kuzmicová et al. propose three embodied affordances in use: "Versatility: the phone provides access to a potentially unlimited wealth of reading materials. Facility: the phone can be operated with the fingers of one hand. Availability: the phone is worn on the body and thus constantly available ... for reading, pending battery life" (338, my emphasis). In a similar line, Hupfeld et al. link technological affordances more with activities than strictly with tools:

In making choices about what platform to read on, people make use of the affordances of current e-reading technology designs, like instantaneity and portability, while giving up some of the values associated with print books, such as visibility and shareability. What we see in people's practices and orientations surrounding e-books is a shift in emphasis from the book as artifact to a set of activities associated with reading. (15).

Then, the mobile e-book is not only a tool, but a practice in itself, one embedded in the practice of everyday life. In conclusion, mobile reading and its technological affordances connect organically with the interactive, movable nature of ambient literature, with "Breathe" as a ghost story that is constructed with the experience of the reader holding the phone, and with the world outside, which actively shapes the story. Jason Farman puts it this way:

As mobile culture continues to take computing out into the physical spaces of everyday life, projects that highlight this experience of multiplicity are the ones that connect with what it means to be embodied in this era of digital culture. Mobile media are less about producing digital simulations that replace the material world and are instead more interested in producing ways that the virtual and the material interact in meaningful, embodied ways. (107).

In the triangulation metaphor, technology as space contains both the story inside and the world outside. While the story is expressed on it, the world around is also experienced, mirrored, transformed, and represented through its affordances at hand, by a human body choosing to use it, in relation to its contents, in some specific situations and not others. In his History of Reading, Alberto Manguel says that "there are books I read in armchairs, and there are books I read at desks; there are books I read in subways, on streetcars and on buses ... Books read in a public library never have the same flavour as books read in the attic or the kitchen" (151-152). While books can be understood here as a specific type of content in relation to specific situations, there is also the particular technological medium embedded in these decisions. "Books" is also the material format content incarnates. And readers, depending on their purposes, choose certain contents in specific technological formats for specific situations.

4. ENVIRONMENT: THE SITUATED SPACE OF LITERATURE IN EVERYDAY LIFE

Environmental space is everything that lies outside the story and the embodied interaction with technology. Or even better, it is the space and time containing the story in the embodied interaction: a room at night, a room at night with the lights off, the daily commute to work, rocking the baby in a crib, standing in a line at the supermarket, having a lunch break in school or work, at the library, in the park, by the seaside.

By now it is hopefully evident how none of the triangulated spaces of the literary experience can work isolated from the other two. This means that if one variable is altered, the whole system will change and the literary experience will become different. The content section explored how "Breathe" fused the real world of the reader with the virtual world of the story. It analyzed how certain genres might pair better with certain environments according to the specific intentions of users. The technological section analyzed how such virtual and real worlds are connected by, and contained in, a medium (the mobile phone) through a set of affordances available at hand, on mobile bodies that enact a literary experience on the move, depending on contents and contexts. Now one can wonder about how the conditions of everyday life, of situated interactions, determine the reading experience, the content, and how technology is used to experience such content in situated manners.

Although this paper proposes that each space contains and is contained in the other two spaces of the literary triangulation, a linear inductive organization of spaces can still be made, from the inner virtual one to the outer contextual. If technology is an embodiment of the story, situational environment can be described as a sort of embodiment of the embodiment, an outer layer of expansion and interaction with the world. This is exactly what Kuzmicová et al. call a "situation constraint," a set of contextual variables that affect and determine the literary experience: "the reader's experiencing body is always embedded in an environmental (e.g., a private bedroom vs. an airport lounge) and broader situational context (e.g., bedtime relaxation vs. time killing in public)" (335).

The environment in which people read is rooted in contextual purposes and motivations that move them towards the act of reading: "As with any body of practice, there are manifest, situated logics that attach to how people reason about their reading practices and these are accountable to the moment, to the social organization in play" (Rouncefield and Tolmie 137). People might read in the subway, or when rocking the baby crib, or during lunch break because they have no other moments to read throughout the day. They might read in the library because they want to concentrate in silence, and they might read in a park because the natural landscape makes them relate better to certain contents of the book, or simply because parks give them a peaceful state of mind for reading. At the same time, purposes of situated reading can depend on the particular affordances of technology:

m-Readers capitalize on this attribute to trade in the mind wandering or boredom potentially awaiting them during the daily commute, in checkout lines or waiting rooms, for mood management via fiction reading. Availability entails that this requires no planning on their part. The attribute of facility, in turn, enables them to begin reading within the few seconds it takes to retrieve the device from a pocket, swipe the screen with their thumb and press a button. More importantly, it enables them to read without any additional physical support also while holding onto a railing, carrying a sleeping infant, or undergoing intravenous therapy. ... Especially in nontraditional reading situations, the device can then serve as an extension proper of the reader's body. (Kuzmicová et al. 338).

Users can choose to read "Breathe" at a particular location in the world, at some moment in time, because of the characteristics of the story (environments more prone to horror), because of the particular affordances of the technology (a free hand to hold the phone while standing in the subway), or because they have time to kill in the waiting room while awaiting their dentist appointment. In real practice, in what this triangulation metaphor tries to understand, circumstances of reading are determined by a series of variables working together. "Breathe" is a short story to be read in less than twenty minutes, on the mobile phone always at hand. If chosen to be read during the daily commute to work, the experience will of course be different, perhaps less uncanny, than if read at sunset while walking through a cemetery. A particular environment determines the impact of the story as much as the story creates an environment for readers and makes them aware of it. It is a cycle that goes in both directions.

When discussing the relevance of understanding environment as an important feature of literature, and ambient reading as an academic subject, Dovey et al. express that:

Cultural work that starts with this proposition offers readers, users and audiences some important potentials for contemporary culture. It offers us encounters with the technological, historical and ecological systems that shape us in the here and now. It puts memory and identity into play with mobility and place. It has the potential not to distract us but to connect us with place and with one another. (20).

Once again, this makes a case for real-life literary interactions not only as immersion, as evading oneself from the world, but also as a way of being in the world and its circumstances, and it offers a clue to understand why this act of looking up and around to the world, in relation to looking down to the page, is aesthetically, culturally, socially, and politically relevant. The common prejudice that reading fiction successfully means eliminating the real environment around readers is in this regard conceptually incomplete, and also technically misguided: "while the relatively high attention demands of reading are well beyond dispute, sensory stimuli from the environment can still inform a reader's consciousness without necessarily disrupting the reading experience" (Kuzmicová 11). In "Breathe," environmental stimuli not only do not disturb the reading experience, but even enrich it in consonance with the reader's surrounding world. In this case, paying attention to the world around means becoming better readers of the inner worlds of fiction we hold in our hands, which are in turn forms of dealing with our own circumstances. For example, the narrative device of "Breathe" of revealing the identity of the ghost as the mother of the protagonist's refugee friend is made evermore meaningful in a terrorizing real environment of human migrants dying when crossing borders. This could perhaps be ultimately interpreted as the real horror behind "Breathe": the ghosts in fiction that are equally present and real in everyday life.

5. CONCLUSIONS

This paper has followed a triangulated logic to situate a specific literary piece, embodied in a specific technology, in real-world environments. In the end, the triangulation metaphor attempts to tell a more complete narrative between what happens in a literary story and the social environments where it is experienced. Its goal is to try to understand why and how literature is enacted in real-life situations, by real-life humans who are not a generalized abstraction, but diverse and unique in many ways.

In any case, this paper has not really measured the extent to which "Breathe" successfully delivers or not a horror experience through location, time, and weather, technological affordances, and conditional text. Rather, it has analyzed how the story incorporates these three spaces consciously and explicitly to create an evident link between fiction and the world: the conscious creation of ambient literature through mobile phone technologies. All three spaces can be considered as one encompassing "literary space" that is studied in line with how literature is actually used in everyday life: a fluid and movable space in the movable circumstances of fluid experiences.

Ambient literature and "Breathe" are excellent examples to showcase these spaces and the spatial system they comprise. Under this light, it is possible to affirm that a spatial triangulation methodology between virtual, technological, and contextual spaces is usable and necessary to understand the experience of literature in real life circumstances, regardless of the technological affordances of the literary medium (either digital or physical). To a certain extent, all literature is ambient literature, and a triangulated spatial approach can help users, researchers, institutions, and policy makers to understand it as such.

Space, as Doreen Massey once again proposes, "does not exist prior to identities/ entities and their relations. More generally I would argue that identities/entities, the relations 'between' them, and the spatiality which is part of them, are all co-constitutive" (10). When studying the production of literary space through the interrelation of its components, it is possible to understand why and how literature is used in real-life circumstances of the real world.

There is a gap in the state of the art of the disciplines studying literature use, its materialities, formats, technologies, and history. This gap is a lack of attention to literary situatedness and has been pointed out by several scholars, amongst them Kuzmicová (3-4), Rouncefield and Tolmie (135), and Hupfeld et al. (3). Especially when studying digital literatures in mobile technologies, much of the research is "surprisingly unsituated, assuming that all reading is the same" (Rouncefield and Tolmie 135). This has to change if there is a disposition to study literature as it is used by real audiences in their everyday life.

Mobile phone reading's reported increasing use suggests that "mobile phones are to some degree being adopted for fiction reading across the entire world" (Kuzmicová et al. 334). There is an immense research opportunity to study situated mobile literature as an expanding phenomenon, and there is likewise an immense opportunity for publishers and cultural institutions to address this reality and produce contents and policies to create literary use out of mobile phones. This applies especially to audiences that have predominantly been left out of literary interactions due to lack of access. But most people now more than ever have and will have access to smartphones.

In the end, "Breathe" is a story about a refugee and his deceased mother, of how a memory of her is present in absentia and tries to reach her son through a medium, from the past to the present, from beyond to "here." Mobile phones also tell the stories of mobile people, and mobile people today (many of them migrants and refugees) do tell and have access to stories in their mobile devices, often when everything else has been left behind at the beginning of their journey, by choice or by force. One example of this can be found in Ai Weiwei's documentary Human Flow (2017), a powerful account of how humans move today with a particular emphasis on people who are forced to migrate against their will. Their stories of mobility are physical and symbolic, cultural and social, inasmuch as they are technological. A constant image in the documentary, a telling picture of today's social and technological reality, is that of migrants and refugees holding and charging, filming, telling, and archiving stories with their mobile phones (Andrews 3), the one thing they could carry along, often when everything else, including other devices of telling and remembering their stories, had to be forcefully left behind.