Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Zona Próxima

On-line version ISSN 2145-9444

Zona prox. no.20 Barranquilla Jan./June 2014

Godofredo Cinico Caspa: a positive discourse analysis

Godofredo Cinico Caspa: Un analisis positivo del discurso

Luzkarime Calle Dfaz

luzkarimec@uninorte.edu.co

Licenciada en Educacion Basica Especialista en la Ensehanza del Ingles Candidata a Maestria en la Ensehanza del Ingles Docente en el Instituto de Idiomas de la Universidad de Norte. Barranquilla-Colombia.

FECHA DE RECERCION: 30 DE NOVIEMBRE DE 2011

FECHA DE ACERTACION: 17 DE ABRIL DE 2014

Abstract

Language is undoubtedly the most powerful semiotic resource in every society. Identities, idiosyncrasies, ideologies, and feelings can be evidenced through, and at the same time constructed by, language. Discourse Analysis aims to discover the intentions and meanings in and behind language and how these can (re)construct social structure, relationships, and change. The purpose of this article is to present a Positive Discourse Analysis of the article Que Privaticen toda la Educacion by Antonio Morales Riveira. The analysis is based on Systemic Functional Linguistics categories within the appraisal (Martin & White, 2005) and transitivity systems (Martin & Rose, 2007; Goatly, 2000). Conclusions are drawn in terms of the representation of students in the public education system as well as implications for educational and research purposes.

Palabras clave: positive discourse analysis, appraisal, transitivity, power relations, stereotypes, social structure, public education.

Resumen

El lenguaje es sin duda el recurso semiotico mas poderoso en toda sociedad. Las identidades, idiosincrasias, ideologias y sentimientos pueden ser evidenciados y a la vez construidos por el lenguaje. El analisis del discurso busca descubrir las intenciones y significados en y detras del lenguaje, y como estas pueden determinar la estructura, las relaciones e incluso el cambio social. El objetivo de este articulo es presentar un Analisis Positivo del Discurso del articulo "Que Privaticen toda la Educacion" escrito por Antonio Morales Riveira. Utilizando la teoria de la valoracion (Martin & White, 2005) y la transitividad (Martin & Rose, 2007; Goatly, 2000), tomando como base la Linguistica Sistemica Funcional, se sacaran conclusiones acerca de la representacion de los estudiantes en el sistema educativo publico, asi como tambien las implicaciones del analisis para fines educativos e investigativos.

Key words: analisis positivo del discurso, evaluacion, transitividad, relaciones de poder, estereotipos, estructura social, educacion publica.

INTRODUCTION

Language is undoubtedly a key resource for the representation and construction of every society. Identities, idiosyncrasies, ideologies, and feelings can be (and are) all evidenced through, and at the same time constructed by, language.

Discourse Analysis has emerged as a way to analyze language and its meaning in a specific context, acknowledging the importance of this analysis to discover and construe culture and society in general, in language. Fairclough (1992) defines discourse analysis as the field that focuses on the social effects of discourse. In his viewpoint, "discourses do not just reflect or represent social entities and relations, they construct or 'constitute' them" (p. 3); that is, discourses have the power to put people in different positions in society according to the values that they defend, that are usually the values accepted by the society in which they stand (Fairclough, 1992).

For more than thirty years, Discourse Analysis (henceforth DA) has focused on the study of the relationship between language and power and how texts serve as a way to disempower certain members of society. This field of DA is widely known as Critical Discourse Analysis (hereafter CDA). Martin (2004) has called this type of analysis CDA realis. It refers to the kind of discourse analysis that deconstructs texts whose purpose is to exercise power through language in a way that discriminates or 'patronizes' certain sectors of society.

The other face of DA is what Martin (2004) calls CDA irrealis, which basically refers to the analysis that is done to texts that aim at emancipating the least powerful groups in society. Janks and Ivanic (1992) define it as a type of discourse that uses "language in a way which works towards greater freedom and respect for all people" (p. 305). This type of analysis has been called Positive Discourse Analysis (henceforth PDA) (Martin, 2004). Macgilchrist (2007) considers that the difference between CDA and PDA would be that PDA "analyses the discourse we like rather than the discourse we wish to criticize" (p. 74).

This article will present a Positive Discourse Analysis of the text iQue Privaticen toda la Educacion! by Antonio Morales Riveira through two metafunctions from Systemic Functional Linguistics, namely, Interpersonal and Ideational. However, not all the resources available in these metafunctions will be tackled.

First of all, from the interpersonal meaning, I will emphasize on the analysis of Attitude in the discourse of Antonio Morales Riveira, although I will also include a very brief account on the Graduation and Engagement resources in the text. The second type of analysis belongs to the ideational meaning proposed by SFL.

I will attempt to discover the role language plays in the Discourse of Antonio Morales Riveira using the framework of Transitivity presented in Goatly (2000) combined with some later contributions by Martin and Rose (2007). Finally, I will also present a brief analysis of other specific linguistic features of the text.

For the analysis presented in this article, I decided to focus on five linguistic features from the list proposed by Janks (2005). The first one is MOOD, "which covers those lexicogrammatical resources which signal different types of interaction between interlocutors in an exchange" (Lavid, Arus & Zamorano-Mansilla, 2010, p. 229). The function utterances serve in a communicative exchange can be classified into four main 'speech functions', namely: statement, question, offer, and command; which are realized through declarative, interrogative, imperative, and interrogative/declarative mood types respectively (Lavid, Arus & Zamorano-Mansilla, 2010). The second one is VOICE, which deals with the agency in the clause (active or passive). The third one is TURN-TAKING which analyses who gets the floor and how participants' turns are distributed in the text. The fourth one is MODALITY that allows interpreting possibility, probability, or obligation in the text. This specific feature is related to engagement from the Appraisal system in the sense that the author uses resources such as hedging or intensification to show his viewpoints in the text. Finally, I will analyze PRONOUNS which can evidence inclusive/exclusive, sexist/non-sexist use of pronouns.

Contextualization

Education in Colombia has experienced many changes in the last few years with the introduction of new policies, and administrative and academic regulations. In the last decades, new discourses have arisen where emphasis is put on the improvement of quality and coverage in education, and where the main focus is to prepare students for the global market. Reforms to primary and secondary education have been introduced with the implementation of curriculum guidelines, and basic competencies standards for specific subjects, as well as new policies in terms of students' evaluation. So far, little had been proposed to change the educational laws ruling higher education since the last law was issued in 1992 (Ley 30 de 1992). However, since 2010, the Colombian government has attempted to introduce major modifications to this law by proposing a reform to the higher education system in Colombia. The proposed reform had four main objectives: "First, generating conditions to have more higher education opportunities; second, generating conditions for more Colombians from poor sectors and vulnerable populations to have the opportunity to enter and graduate from higher education centers; third, adjusting the higher education system to the national reality and harmonizing it with regional and international tendencies; and finally, strengthening the principles of good governance and transparency in the higher education sector" (Translated from ABC de la Reforma a la Educacion Superior en Colombia, published in "Al tablero", electronic magazine from National Ministry of Education).

By reading these objectives, anyone would think that the new reform was beneficial for the academic community, for students and for improving the quality and coverage of higher education centers. However, the terms in which the reform was stated created controversy among students, teachers, and even principals in the different public universities. Four of the main arguments against the reform proposed by the government were: First, it would allow the private company to invest resources in public universities. The representatives from public universities believe that private companies would invest only if they could make a profit out of it, so they fear that their interest would collide with the mission and function of universities. Second, the government would increase the amount of money given to public higher education centers; however, public universities claim that this money is not enough for universities to support the number of students they have and would have in the future (the law also intended to increase the number of students entering the university). Third, the reform allowed the conformation of profit-making universities. This is extremely controversial because it might endanger the quality of education if the goal of universities is maximizing profit with little investment, as any profit-making company does. Finally, public universities representatives fear that, as the National Ministry of Education would have more power to closely supervise and control their quality processes, public universities would lose their autonomy (N.A, 2011).

We can see, then, that arguments for and against the reform were strongly built and the discussion about the issue was present in the academic scenarios of the country. Furthermore, the students of all public universities in Colombia (and some private institutions) gathered to protest against the reform, causing the whole country to turn their attention to what was happening. The classes were stopped until the reform was finally withdrawn from the Congress.

Objective

The purpose of this article is to show how the article "Que privaticen toda la Educacion!" by Antonio Morales Riveira constructs a representation of the students of public universities in order to create societal alignment with their goals, as well as a representation of the social stratification as valued in the Colombian society. It also attempts to evidence the author's intention to raise awareness on the common sense that elite classes have about social division and how an important part of society perceive the right to access higher education and labor market in Colombia.

General Description of the Text

The text "Que privaticen toda la Educacion! is an article written by Antonio Morales Riveira, Colombian anthropologist, journalist, researcher and critical writer. He has won several journalism and writing awards in Colombia. He created the character of GODOFREDO CfNlCO CASPA to depict and thus set a voice of protest against political, economic and social issues in Colombia through the genre of satire. As it is typical from this writer, the genre of the text is Satire. This genre is characterized for ridiculing vices, abuses, and faults, with the purpose of embarrassing individuals and society, aiming at improving social situations. Albeit meant to be funny, the ultimate goal of satire is constructive social criticism, using wit as the excuse. The presence of irony and sarcasm are common in satire, and allow the writer to present as acceptable or even desirable, what he or she actually wants to criticize (Wikipedia, 2011). In his articles, Morales Riveira signs with his pseudonym (Godofredo Cinico Caspa) to suggest that the opinions are expressed by this fictional character and not by him.

This text, published in the column of the magazine "Kien&Ke, el placer de saber mas", was chosen based on the fact that the writer has caused a lot of controversy in Colombia with his style of writing. By using the genre of Satire the author has been able to trigger people's reactions against certain Colombian social conventions or 'common sense'. This article specifically addresses the topic of education and educational system in Colombia. It evidences from the very first line the intention of the author to flout the statutes of the education system in Colombia.

It is necessary to clarify that the text is ironic and sarcastic in nature and that its purpose is to put on the spot a proposed reform to the educational system in the country. The author uses the scenario of this proposed reform to the educational laws (reforma a la Ley 30) to highlight the different status that certain sectors of Colombian society value and to bring into the scene some other political stances which he strongly criticizes.

First, the text talks about the way our society is conceived and the accepted beliefs about positions in society. Then, the author discusses the central topic of the text, namely, the reform and the eventual privatization of the universities in Colombia. Finally, he criticizes governmental decisions in terms of resources investment and how education is being neglected to give more importance to the war against guerilla and drug dealing groups.

ANALYSIS

Appraisal

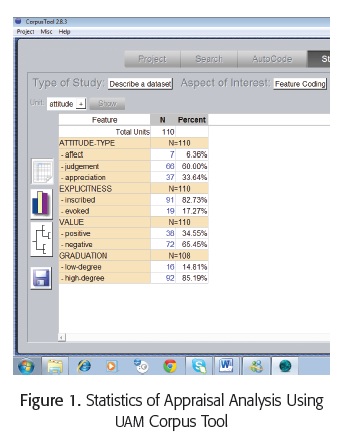

The appraisal analysis was done through "UAM Corpus Tool", software that proves very useful in this endeavor because it provides clear statistics about the resources found in the text analyzed. A summary of the results of the analysis is presented in figure 1.

We can see many interesting aspects in the author's intention for writing this article. In terms of Engagement, the article is mostly monoglossic.

We can generally hear only the voice of the writer (e.g. debo empezar con un andlisis general del tema de la educacion; Y pongo de presente mi posicion general frente al tema; Desde ya le exijo al ESMAD que actue de manera implacable). However, in some clauses we get the impression that the writer is speaking as a member, hence on behalf of certain groups of society (e.g. que nos permitird tener lindas universidades publicas-privadas de tercera y de quinta; Exijo el derecho que tienen mis amigos a tener universidades privadas). Also, he asks some questions as to allow the reader to take some voice, but he immediately interrupts him or her by answering the questions himself. Therefore, I would dare to say that the text is also heteroglossic in some extracts (e.g. <LQue no habrd plata para postgrados? iY que! IPensamiento crftico y arte? Vainas supera-das despues del gobierno de Uribe y de Dios.).

Regarding Graduation, the statistics from UAM Corpus Tool show that 85,19% of the appraisal resources in the text evidence high-degree (e.g. la peligrosa izquierda; ese estudiantado gamin ysubversivo;losguerrillerosde las ONG...). The author uses strong adjectives to exaggerate his "disregard" for lower classes.

Concerning Attitude (See figures 2 to 5), which is the aspect of Appraisal that I emphasized in the analysis, there are many conclusions that can be drawn. To start with, the article begins with an introduction of the "writer", which clearly shows a negative appreciation of himself, and therefore, of the people he represents (Soy Go-dofredo Cfnico Caspa, formador de juventudes, educador en Ralito, docente de catequesis en casa de Jorge 40, maestro de etica y profesor de derechos humanos en la Escuela Superior de Guerra y presidente de la ANUG, Asociacion National de Universidades de Garaje). This shows the reader from the very beginning the stance that the real author is taking and the sarcastic nature of the text. It also evidences the purpose of the reader to suggest the relationship between government and "upper class" agents with certain armed group in Colombia. Another example of this is found later in the text (donde tenemos las mayorfas gracias a los ya viejos buenos oficios de los pioneros Mancuso y Castano). Jorge 40, Mancuso, and Castano were former members of the armed group Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia (AUC), demobilized during the previous government term of office.

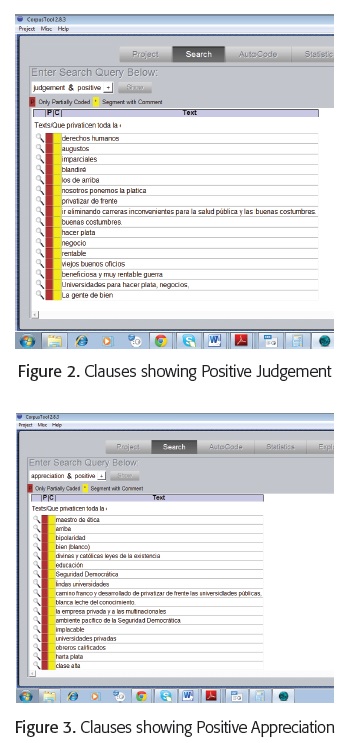

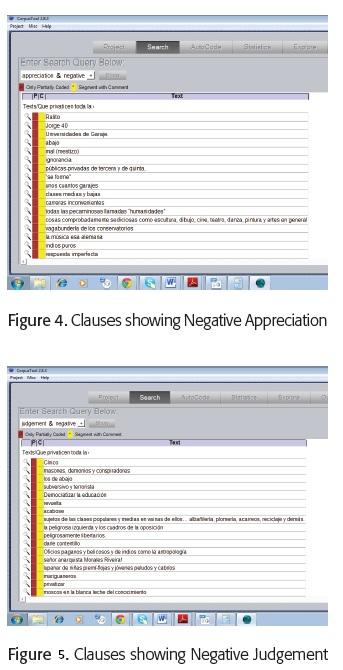

Judgement and Appreciation stand out in the text. Judgement is always positive when referring to the "upper class". Also, it is positive when showing the "benefits" that privatizing universities will bring to society (e.g. , la educacion es cosa de los de arriba; vainas que le sirven a la empresa pri-vada y a las multinacionales para hacer plata; Defensa para seguir eternamente la beneficiosa y muy rentable guerra contra la subversion y la cocafna. Universidades para hacer plata, negocios). On the other hand, Judgement is always negative when talking about the "lower class". The author uses high-degree negative attributes to identify the members of this class (e.g. guerri-lleros, mariguaneros, enemigo, indiada pelilarga y chirosa, enemigo, subversivo, terrorista, etc.). He also evidences negative Judgement when referring to public universities and the humanities, careers where you usually find people from lower economic strata (e.g. No mas universidades como la Nacional, la de Antioquia, la Distrital o la del Valle... para que "se forme"lapeligro-sa izquierda y los cuadros de la oposicion en general; ir eliminando carreras inconvenientes para la salud publica y las buenas costumbres. Oficios paganos y belicosos y de indios como la antropologfa ... sociologfa, filologfa, historia, geograffa, filosoffa, sicologfa... Mejordicho todas las pecaminosas llamadas "humanidades" que son tan solo un lupanar de ninas piernf-flojas y jovenes peludos y cabrfos).

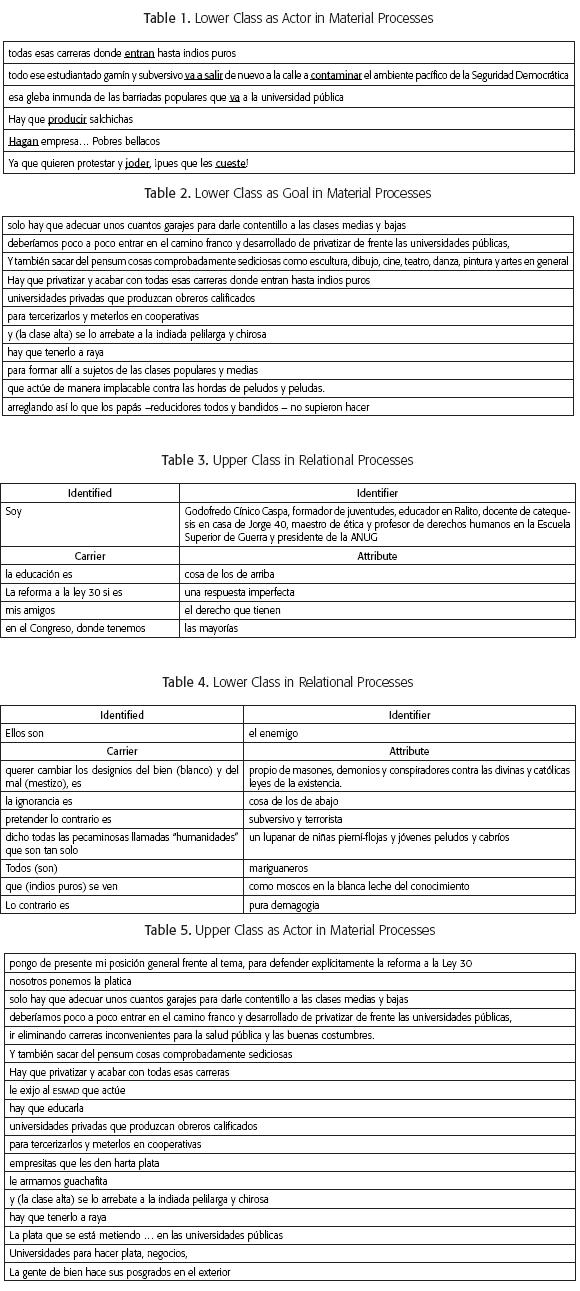

To continue, the author expresses positive Appreciation when talking about private universities, rich people, money, private companies, and education as a right of "upper classes" only (e.g. la edu-cacion es cosa de los de arriba y la ignorancia cosa de los de abajo; Exijo el derecho que tienen mis amigos a tener universidades privadas que produzcan obreros calificados para tercerizarlos y meterlos en cooperativas; La gente de bien hace sus posgrados en el exterior y sin plata del Estado. 'Aprendan carajo!). Again, Appreciation is negative when speaking about "lower class" members and public education in general.

Transitivity

The analysis of transitivity in the text provided many insights on the type of processes predominating in the Discourse and the role of participants. For the purpose of this paper I have decided to focus on the role of two participants in the text: the upper class and the lower class. The results of the analysis are presented in tables 1 to 5.

As we can see from this analysis, the "upper class" grouping is presented as the actor in most of the material processes. On the other hand, the "lower class" is shown as the main goal of the "upper class" doings (e.g. nosotros ponemos la platica; hay que adecuar unos cuantos garajes para darle contentillo a las clases...ir eliminando carreras inconvenientes para la salud publica y las buenas costumbres; hay que privatizar y acabar con todas esas carreras; para tercerizarlos y meterlos en cooperativas). When we look at the relational processes, the "upper class" is always presented with what we would say are positive attributes (e.g. el derecho que tienen mis amigos, la educacion es cosa de los de arriba). On the contrary, the "lower class" is allocated negative attributes such as subversive, terrorist, drug addicts, among others (subversivo, terrorista, mariguaneros, moscos, pierni-flojas, jovenes peludos).

Other features

For the analysis of other linguistic features in the text, I decided to choose the most salient paragraphs of the article, which give the reader the necessary tools to interpret the author's arguments and to understand the satirical humor presented by the text.

In terms of MOOD, the writer generally uses the statement speech function with Declarative mood. However, there are seven commands in imperative mood. This gives the impression that the writer thinks he has the power to tell other people what to do. He also includes three interrogative utterances with immediate answer. (IPensamiento crftico y arte? Vainas superadas despues de ocho anos de gobierno de Uribe y de Dios).

Regarding VOICE, all the clauses are in active voice except for Mejor dicho todas las pecaminosas llamadas "humanidades". In this clause, the writer implies that other people call the subjects "humanities", he does not specify who, but it is clear that it is not him or the people he represents.

As for TURN-TAKING, only the writer (upper class) controls the topic. When he gives the turn to the readers by asking a question, he immediately silences them with his "apparently correct" answer. When he gives the turn to the "lower class" is just to command them to do something in a very rude way (iaprendan, carajo! iHagan em-presa, pobres bellacos!) The "lower class" voice is never heard.

Regarding MODALITY, almost all clauses are categorical. The writer uses obligation (hay que) to give his opinion about what the people he represents have to do. This can be interpreted as if he has power over these people ("the upper class"). He uses possibility (de no ser possible) to give alternative ways to do something to the "lower class". He uses certainty (will) to express the "benefit" that their course of action will bring to society (nos permitird tener lindas universidades publicas-privadas de tercera y de quinta). However, he also uses certainty in a negative interrogative clause (Que no habrd plata para postgrados?) to disclaim possible counter-opinions from "lower class".

Finally, in terms of the use of PRONOUNS, In some clauses, the writer uses we to talk about him and the "upper class" (deberfamos poco a poco entrar en el camino franco y desarrollado de privatizar de frente las universidades publi-cas/ en las cuales nosotros ponemos la platica). However, in some others he is not part of this "upper class" and he uses they to refer to them (Que dejen ingenierfas y cosas asf, vainas que le sirven a la empresa privada y a las multina-cionales para hacer plata; la gente de bien hace sus postgrados en el exterior). In all cases he uses they and you to refer to the "lower class" (a sujetos de las clases populares y medias en vainas de ellos... albanilerfa, plomerfa, acarreos, reciclaje y demds; que se ven como moscos en la blanca leche del conocimiento; iHagan empresa. Pobres bellacos!), clarifying that he is not part of them.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, considering the satirical humor of the text, the intention of the author is to strongly criticize the social division of our society and the little attention paid to important decisions such as changes in the education system of the country. The text also shows clear stereotypes in our society about students, education, and social stratification.

The text mostly empowers the high social classes (whites, government, entrepreneurs) by showing them as powerful agents able to make decisions and control the lives and future of others. It di-sempowers the students of public universities, the employees, and the low social classes in general, by presenting them as voiceless or as subversive, rebellious, drug addicts and good for nothing more than "low class" jobs. They are also presented as agents of "bad" actions for society, such as artistic and literary endeavors, and research, which on the contrary are widely recognized as very important ways of creating social change and development.

Due to the satirical genre of the text, we can see that the opinion of the author is exactly the opposite and his intention is more to emancipate this low social class and encourage them to make a change and to act against this social disempowerment that society has put over them. By showing an exaggerated "common sense" of our society, he intends to criticize what we accept as natural and invite people to become aware of what is really happening with our values and what can happen in the future if we do not get involved as important members of society.

By carrying out these types of analysis, we as teachers and researchers can become more aware of the pivotal role that language plays in influencing other people in society. More importantly, by being directly involved in language teaching, we can start to put into practice these analyses in class with our students in order to make them more critical towards the information that they receive every day. This analysis also serves the purpose of creating a feeling of engagement in social change and the consciousness of the fact that there are many actions that we, as citizens, can take to make a change in society. This analysis has also awaken a strong interest in Discourse Analysis and has opened my understanding as to the values of Colombian society and the ethics and principles that are spread and "sold" as correct and that everybody seems to accept as natural.

In terms of education, I consider that all teachers and researchers should definitely get involved in the analysis of Discourse in one way or another, so that we can really start keeping the promises of the Education of the 21st century, of forming integral citizens of the world, able to think critically and make wise decisions that affect society in a wholesome way.

REFERENCES

Fairclough, N. (1992). Discourse and Social Change. Cambridge: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Goatly, A. (2000). Critical Reading and Writing: An Introductory Coursebook. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Janks, H. (2005). Deconstruction and Reconstruction: Diversity as a productive resource. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 26(1), 31-43. [ Links ]

Janks, H., & Ivanic, R. (1992). CLA and Emancipatory Discourse. In N. Fairclough (Ed.), Critical Language Awareness (pp. 305-331). London: Longman. [ Links ]

Lavid, J., Arils, J., & Zamorano-Mansilla, J.R. (2010). Systemic Functional Grammar of Spanish: A Contrastive Study with English. London: Continuum. [ Links ]

Ley 30 de Diciembre 28 de 1992 (1992). [ Links ]

Macgilchrist, F. (2007). Positive Discourse Analysis: Contesting Dominant Discourses by Refram-ing the Issues. Critical Approaches to Discourse Analysis across Disciplines, 7(1), 74-94. [ Links ]

Martin, J. R. (2004). Positive Discourse Analysis: solidarity and change. Revista Canaria de estudios Ingleses, 49, 179-200. [ Links ]

Martin, J.R., & Rose, D. (2007). Working with Discourse: Meaning behind the Clause. London: Continuum. [ Links ]

Martin, J.R., & White P.R.R. (2005). The language of Evaluation: Appraisal in English. New York: Pal-grave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Ministerio de Educacion Nacional (n.d.). ABC de la Reforma a la Educacion Superior en Colombia: al tablero. Retrieved from http://www.mineducacion.gov.co/1621/article-283356.html. [ Links ]

Morales, A. (2011, August 14). Que privaticen toda la educacion. Kien&Ke. El placer de saber mas. Retrieved from http://www.kienyke.com/2011/07/14/%C2%A1que-privaticentoda-la-educacion/. [ Links ]

N.A. (2011, April 1). Reforma a la ley 30: por que si, por que no. Semana.com. Retrieved from http://www.semana.com/nacion/reforma-ley-30-no/154361-3.aspx. [ Links ]

O'Donnell, M. (2007). UAM CorpusTool (version 2.7) [Software]. Available from http://www.semana.com/nacion/reforma-ley-30-no/154361-3.aspx. [ Links ]

Propuesta de reforma a la ley 30 de 1992 (2010). Wikipedia (2011). En linea: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Satire. [ Links ]