Introduction

The ongoing financial and economic crisis has impacted Latin America like never before. The external channels of transmission differ from the past crisis, specially the trade channels. Collapse on trade has been very strong and has affected exporters through the reduction of world’s demand; also, primary commodity exporters have suffered the collapse of international prices.

This paper takes a first look at the impact of the free trade policies adopted by the region (Latin America Selected Countries) and if this path is a sustainable way to recover the economies from the world crisis, based on a literature and statistical review. It is divided into five sections. The first made a review of the trade and growth theories. The second takes a brief look at the impact of trade openness on growth. The third, analyses the trade as a channel of transmission of the crisis to Latin America. The fourth, considers the impact of growth on income and poverty (as a measure of sustainable growth). The fifth draws some conclusions and raises questions on the region’s export development strategy.

Evolution of trade and growth theories

The classic theory of trade as described by Smith, Ricardo, Mill and others, is based on a set of important assumptions or abstractions of reality. Cost of transportation was omitted and it was assumed that production factors were mobile within the country, but immobile internationally. Comparative cost was static, a gift of nature, and could not be transferred from one country to another. The theory was also based on the belief of the value of labour, i.e., the assumption that the quantity and efficiency of the labour input are the main determiner of the production cost.

Beginning with the pioneering ideas of Smith, Ricardo established the “theory of absolute comparative advantages” as the fundamental reason of free trade. This law demonstrated that the commercial flow between countries is determined by the relative (not absolute) cost of the goods produced. International division of work was based on comparative costs and countries would tend to specialize in those goods whose costs were comparatively lower. This simple notion of the universal benefits of specialization based on the comparative costs is still the key to the liberal theory of the international trade.

Under a perfect free trade system, each country naturally dedicates its capital and labor force to those employments more beneficial for each other. This quest for individual advantage is wonderfully linked to the joint development of the exchanging agents.

Recent theoretical developments have incorporated the theory of endogenous development, which has generated a series of models highlighting the importance of commerce in attaining significant sustainable economic growth rates. Such models have emphasized multiple variables, such as the degree of aperture, real exchange rates, customs duties, exchange terms and export performance, to illustrate that open economies show superior growth rates to closed economies (Balassa, 1978; Edwards, 1998).

Even if many of these models emphasize trade, consider it as only one variable to account for within the growth equation. However, the defenders of the Export-Led Growth (ELG) hypothesis have established that trade was the main factor for the growth of the economies of South East Asia. They maintain that the Asian Tigers (Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore and Korea) have been successful in attaining high sustainable growth rates due to their market economies being oriented abroad.

At the beginning of the 1980’s there was a wide consensus among researchers and policy makers about the ELG and the promotion of exports which grew into a kind of “popular wisdom” for economists in developing countries (Tyler, 1981; Balassa, 1985). It is still the mainstream of thought of many a policymaker and multilateral institutions such as the IMF and the World Bank.

Defenders of ELG and free trade emphasizes that the approach of Import Substitution Industrialization (ISI) led the countries, mainly Latin American, following it to low economic growth rates (Balassa, 1980). Moreover, some of them demonstrated an absence of growth and a deterioration in real income between 1960 and 1990 (Barro and Salai-Martin, 1995). These facts led to a change in the direction of literature during the 80’s. Authors such as Bruton (1989) argued that ISI strategy led the Latin American countries to depend on short-term capitals, which supported imports and consumption levels; this was the main cause of the severe impact that the 80’s crisis had on Latin American economies.

Following that crisis multilateral institutions forced the implementation of the open ELG model with the objective of implementing programs for adjustment and stabilization of the macroeconomic indicators. The strategy consisted of opening the market and giving incentives to exports as the most suitable and reliable mechanism for the attainment of good indicators, for the correction of imbalances in the external sector and for the recovery of economies. The stabilization programs provided the policymakers in Latin American developing countries with new tools for the formulation of external policies. Development of exports became a priority for the governments, and thus, they turned to various mechanisms such as subsidies, tax exemptions and other promotional instruments.

Consequently, contemporary literature also changed. ISI approaches gave way to external approaches. Economic opening and ELG became the central focus. Therefore, a new popular wisdom was reached. This model would allow the countries to recover their growth rates and would result in the improvement of their people’s standards of living. Each strategy concerning the growth model has been subjected to rather exhaustive theoretical and empirical revisions. The interesting point here is that while literature proposes a relationship between trade and economic growth (Adams, 1973; Crafts, 1973; Edwards, 1992), the empirical studies look for a relationship between exports and growth (Levine and Renelt, 1992: 953).

Even though the literature regarding ELG considers the role of exports and focuses especially on its links to economic growth, the studies conducted since the 60´s have led to a careful examination of the role of the export performance and its incidence on economic growth. In this respect, the results shown in the literature are clearly contradictory for developed and developing countries.

According to multilateral institutions and many orthodox economists, promoting exports benefits developed countries as well as developing countries. Such statements rest on the principles of: efficient usage of existing capacity, economies of scale, technological advancement, employment generation and labour productivity. They also rely on efficient productive resource relocation and correction of imbalances in the balance of payments through increased income and foreign investment, which eventually increases the total factor productivity and in consequence, improves the welfare of the countries (World Bank, 1993).

Since the theory seems to suggest that virtually nothing can hinder productivity growth after the trade aperture, the question about commercial trading and productivity has become a question of empirical character. Micro and meso evidence (at company and industry level) provides a relatively solid support to the positive effects of trade upon growth at this point.

Such evidence stems from studies conducted by Ferreira and Rossi (2003) for Brasil. Macro studies have also been conducted. Although Dollar (1992), Sachs and Warner (1995) and Edwards (1998), using different opening measurements, constructed, in many cases based on standard political measurements, proved the positive effects of commercial trade on growth, their work has been strongly criticized by Rodríguez and Rodrik (2001) due to problems related to commercial aperture measurements and to the econometric techniques employed, as well as to the difficult task of establishing opportunity management.

Furthermore, while Rodríguez and Rodrik (2001) have criticized the measurement of opening employed by Sachs and Warner (1995) for taking into account many aspects of the macroeconomic environment in addition to trade policy; Baldwin (2003) has recently championed this approach under the argument that other policy reforms adopted the measures, even if they do not constitute trade reforms, per se, they complement the majority of the reforms fostered by international institutions.

The impact of openness on growth

There is evidence that these openings are not entirely beneficial for the countries with low to medium income, and the scarce correlation between openness and growth is even more evident in empirical works. Commercial openings which were adopted in Latin American countries in the 90’s brought with them great liberalization of financial markets. So, the capital flows towards the economies of the continent generated contradictory impacts. The massive arrival of capital forced a revaluation in the exchange rate even more than the revaluation induced by reduction of inflation. This occurred in parallel with the stability of the nominal exchange rate. On the other hand, the revaluation of the real exchange rate in respect to the dollar slowed down the impact of exports and favored imports. After being strongly positive in the 80’s, thanks particularly to the export subsidies and the protection of imports, the trade balance became strongly negative due to the liberalization of markets and the revaluation of the real exchange rate.

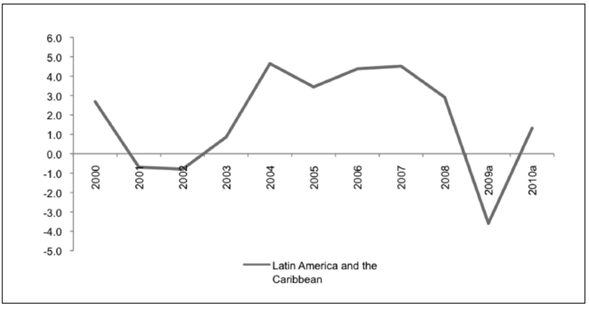

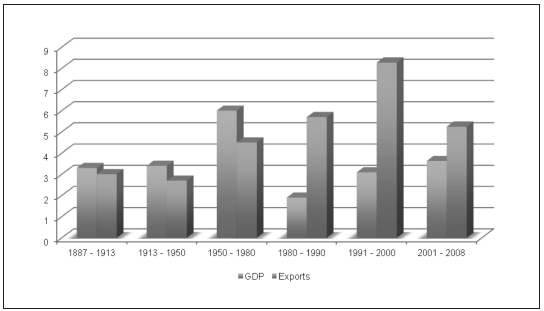

Thus, this condition contrasts with the situation experienced by Latin American countries in the first years of the sudden extensive liberalization of their economies. It is interesting, without necessarily inferring a causal correlation, to point out that the verifiable relationship between the growth of exports and the growth of GDP does not corroborate that which theoretical studies and international organisms attempt to establish: as a contrast between theory and observation. It is evident that high growth in exports corresponds to low growth of the GDP, while low growth of exports corresponds to high growth of the GDP (see Figure 1).

Source: Author based on World Bank, WDI, 2009.

Figure 1 Mean Growth of GDP versus Mean Growth of Exports, World Figures, (%).

In the 90s, the accelerated opening of economies led to a somewhat significant restructuring of production systems in Latin American economies. Some of these tended to become considerably primary whilst others specialized in the export of manufactured in-bond assembly products from “maquilas” with very low added value. Others opted for an intermediate path, characterized by a “deverticalization” in their production line, but without incorporating actual components of research and development to their productive apparatus. In any case, everyone experienced an important opening; between 1985 and 2000, exports grew five times in Mexico, three times in Argentina and twice in Brazil.

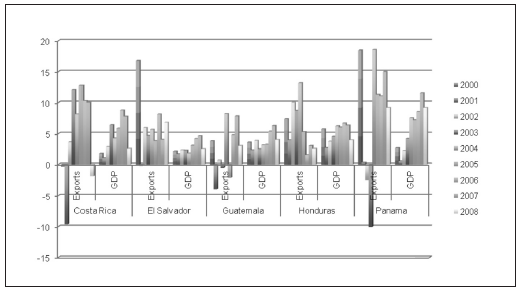

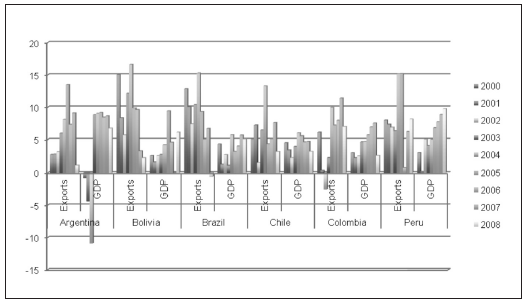

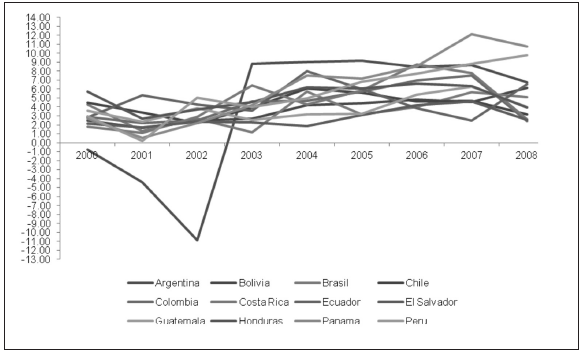

Those economies that did not reprimarize, either the rapid expansion of manufactured exports, or, in some cases, the transformation of their contents, were not sufficient to compensate for the increase of imports during the stages of rapid growth (deterioration of terms of exchange), however the gap tended to close (ECLAC, 2004). The transformation of a negative trade balance result into a positive one still depends considerably on the level reached by the growth rate. As a whole, Latin American economy showed positive indicators in exports during 2000 and 2007; however, the same trends from the former decades are evident. The impact on exports is not reflected in the same way in the growth of the GDP (see Figures 2 and 3).

Source: Author based on World Bank, WDI, 2009.

Figure 2 % Growth of the GDP versus % Growth of Exports, Central America (Selected Countries).

Source: Author based on World Bank, WDI, 2009.

Figure 3 % Growth of GDP versus % Growth of Exports South America (Selected Countries).

Trade as a channel of transmission

Trade has demonstrated to be pro-cyclical since 2000. This feature has been visible in the growth of the volume of international trade as well as in commodity prices. Since the Latin American economies have had a strong ELG orientation over the past two decades, the trade contraction explains why the region has been so severely affected.

Between 2003 and 2006, the volume of international trade increases at 9% per year, more than twice the rate of growth of world GDP that was about 4% (United Nations, 2009A 2009). By the second semester of 2007 started to reduce and it experienced a remarkable contraction during the last quarter of 2008. This reduction is several times the expected reduction of world’s GDP. The most affected economies were those most open to trade, which explains the fall of GDP in the most trade-dependent economies like the case of Latin American countries.

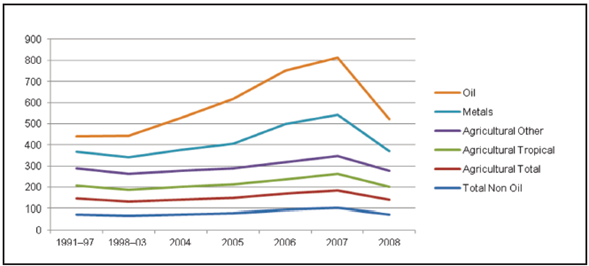

The contraction in world trade volumes was the main transmission channel of the crisis towards Latin American countries that specialize in light manufactures and services, particularly in Central America and some Caribbean countries; in South America the effect depended on the volatility of commodity prices. The boom of commodities (specially oil and mining) from 2004 to second quarter 2008, helped the world economy to show the best indicators in over a century (World Bank, 2009). However, as Figure 4 indicates, the boom was not that good for agricultural goods. And finally both started to fall at the end of 2008.

Source: Author based on ECLAC (2010). Statistical yearbook for Latin America and the Caribbean, 2009; World Bank, WDI 2009; UNCTAD Commodity Price Statistics on-line 2009.

Figure 4 Real commodity prices, (1980 = 100).

A major implication of this is that, in Latin America, the countries that get most advantage from the commodities boom were all oil and mining exporters (from Venezuela to Chile). On the other hand, agricultural exporters (mainly Argentina and Brazil) experienced only moderate and late improvements in their terms of trade.

The difference in performance between oil and mining and agricultural goods indicates that the determinants of both commodity groups have been very different. In the first case (oil and mining) goods, the boom was leaded for a low production capacity and a high demand generated by rapid world economic growth leaded for China (strong demand for metals). In the case of agriculture supply-demand imbalances were more moderate and were more rapidly corrected.

International trade is probably the most important channel for the transmission of the current crisis to Latin America. Its contraction was reflected in the fall down of export revenues (contraction of 30% on a yearly basis - World Bank 2009). The effects on GDP have been dramatic, given the significant openness of Latin American economies today, but the historical experience indicates that crises can provide benefits in terms of economic diversification; however, to fully benefit from them, the region may need to rethink its production development strategy in order to avoid negative effects of external shocks.

Growth and its impact on income and poverty

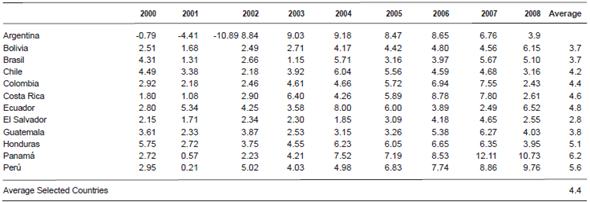

According to the work of Wodon (2000: 7, 56), the net elasticity of poverty with respect to growth is -0,94, which means that for a growth of 1,0%, poverty is reduced by 0,94% under ceteris paribus conditions. Given these verifications, what has happened to growth in Latin America? As shown in Table 1, economic growth is scarcely regular and not too sharp. Growth stayed low for more than ten years in Latin America (1998-2000), and started to rise at an average of 4,4% between 2000 and 2008 (the phase of boom and openness for the majority of economies in the region).

Table 1 Evolution of the growth rate of GDP in the main countries

Source: Author based on ECLAC (2010). Statistical yearbook for Latin America and the Caribbean, 2009.

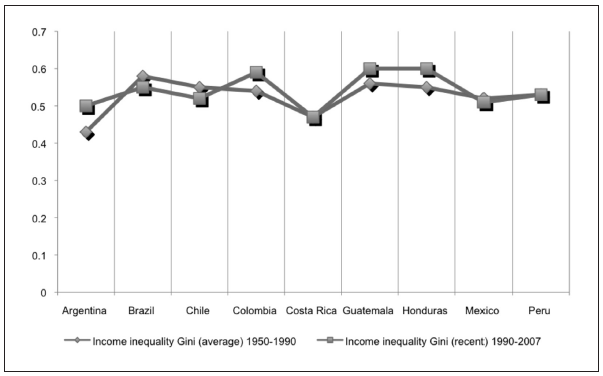

On the other hand, inequality between capital and labor tends to increase, as well as the inequality between qualified and unqualified labor. As shown in Figure 5, income distribution, limited to labor income, became more unequal in most of the countries in the period of great boom and openness (1990 2006).

Source: Author based on ECLAC (2010). Statistical yearbook for Latin America and the Caribbean, 2009.

Figure 5 GINI coefficient, Comparative 1950 - 1990 vs 1990 - 2006.

A low growth rate, associated with a more unequal income redistribution, prevents many of the poor crossing the poverty line. The levels reached by the growth rates and the evolution of the income distribution have not had almost any effect on poverty, except in the very first years of economic stabilization. Another factor involved in the magnitude of poverty is the pace of growth, which has not been regular in the region.

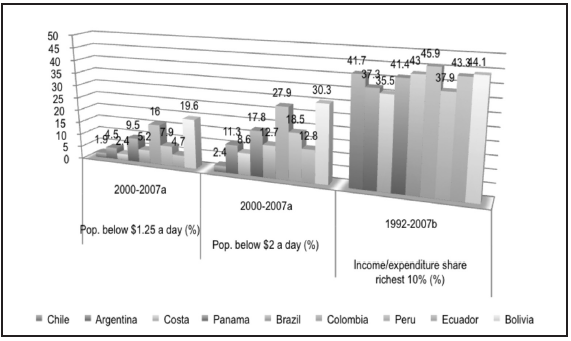

If these figures are broken down into population (poverty, extreme poverty and the income/expenditure of the richest deciles) the situation becomes even more dramatic, as shown in Figure 6.

Source: Author based on World Bank, PovcalNet, 2009; WDI, 2009, CepalStat, 2009.

Figure 6 Poverty, Extreme Poverty and the Richest Deciles (selected countries)

According to the studies of Hicks and Wodon (2001) it is shown that the elasticity of welfare spending with respect to GDP is greater than 1 (in the growth stages as well as in the recession stages). It is also concluded that, if governments adopt poverty reduction policies in periods of growth, this attitude is modified in the periods of recession so, social spending decreases when it should increase, i.e. at the time when the poor suffer a deeper recession than the other population groups. For each percentage point GDP, the poverty reduction programs lose 2%; this effect has two components, on one hand the reduction of the GDP and on the other hand the increase in the number of poor people.

In contrast, when economies recover, poverty does not tend to decrease, not even in the two years following the economic improvement. In the two following years’ poverty even tends to increase and needs longer periods of sustained growth to start reducing. It is this marked growth volatility factor, as shown in Figure 7, which explains the incapacity for significantly reducing the magnitude and the depth of poverty.

Source: ECLAC (2010). Statistical yearbook for Latin America and the Caribbean, 2009.

Figure 7 Behaviour of GDP in Latin America (selected countries)

Controlling growth is not an easy task, even less so is achieving regular growth. As a matter of fact, growth volatility is not a governmental issue. It is an issue of the international economic system. The need to be inserted into in the global economy and, to be more precise, the fact that a great part of the Latin American governments has adopted the paradigm of the neoliberal model as fostered by the Consensus of Washington, adding to the PEM2 predominating in the region (Buitrago, 2006 2007) and to the high dependence on foreign capital, explain to a great extent the volatility of the Latin American GDP.

The crisis add some interesting facts to the previous statements, as shown in Figure 8, forecasts point to a sharp 3.6% contraction in GDP per capita during 2009 followed by a modest rebound of 1.6% in 2010 (OECD, 2010).

Conclusions and implications for the export development strategy

The region’s development has been marked by low rates of technical progress, by low levels of value added to its natural resources and by the use of imported technologies, all of which reflects a reliance on imitation rather than original thought. The region’s recent history has exacerbated its chronic difficulty in sustaining a growth process whose benefits are shared more fairly. In fact, over the past 25 years the region’s pace of growth has been slow and volatile, and income distribution, in some countries, has worsened (see Figure 5). As a result, poverty levels in the region have increased both in absolute terms and as a percentage of the total population as shown in figure 6.

The empirical evidence also seems to show that the most successful economies in terms of growth are those that export high and intermediate technology manufactures. The studies conducted by Ocampo and Parra (2007)) and Rodrik (2006) both provide some evidence on this point. However, although an export basket concentrated in primary commodities (or products based on them) would appear to have a less dynamic effect on growth than exports of manufactures, particularly high-tech ones, the region’s experiences show that exports of manufactures do not necessarily entail a qualitative leap to more complex, technology-intensive goods.

As shown in this document the crisis (external and domestic) in Latin America affects growth, wages, poverty reduction and output. Latin America has been hardly impacted by the current world economic crisis; the external factors that facilitated the 2003-2007 boom are now operating in the opposite direction. The gravity of the impact that Latin America has experienced can only be explained by the severity of the trade shock.

Trade liberalization (Bilateral agreements or Free trade agreements) are certainly important for various reasons, one of the most important being the generation of new markets, but in no way do they guarantee a simple solution for the complexprocess of growth. Nor did the structural reforms of the 1990s, particularly economic liberalization - possibly one of the most overblown (and overacted) components of the package of recommendations to have emerged from the Washington consensus 3.

Trade conditions will remain unstable for a certain time, Latin American economies would be forced to look back to their domestic markets. This should not imply a return to the protectionism path, but it would mean look for alternative production sector development strategies, including activity technology policies (ECLAC, 2008A). Diversification of exports leads to less export volatility, which in turn results in lowered output volatility.

We should also bear in mind that exports may be the solution to the growth problem only in very small economies where integration into world markets is enough to ensure full employment resources. In larger economies, growth depends, to a great extent, on the performance of activities that produce goods and services for the domestic market. Thus, in these economies, development cannot be seen solely as a function of export activities.