Introduction

In the 20th century, the condition of women has greatly improved in several aspects. However, the gender gap is remarkable in the lack of access to power and leadership positions compared with men and women managers are still in a minority (Carli et al., 2001).

Generally, women are less frequently found in line positions than men and more frequently in staff positions and consequently they have less opportunity to demonstrate their competencies (Wiggins, 1996), and even in female-dominated occupations, men have more opportunity to be promoted to the top (Broadbridge, 2010). The 2011 Catalyst Census showed that in 2010 women held 14.4% of Executive Officer positions and 7.6% of Executive Officer top earner positions (Catalyst, 2011).

When considering the healthcare sector, the promotion of women to senior management positions in healthcare organizations has been shown to be slower in comparison with men even when most positions are held by women. The same happens to financial benefits which seem to decrease for women and expand for men as their respective careers advance. Moreover, researches in USA have demonstrated that, in the last years, little has been made to close the gender gap in healthcare leadership especially among the nation’s top hospitals (Branin, 2009).

The same evidences have been also found in Italy where, independently if public or private organizations, women have more limited possibilities to advance in their careers. The percentage of women on boards and senior-executive teams remains one of the lowest among European countries (7% compared with 33% of women in Scandinavian countries). Italy, in fact, ranks 74th out of 134 countries in the Gender Gap Index 2010, immediately followed by Colombia, Vietnam and Perú. 35% of the Italian women in the age of 25-44 is unemployed (21% is the average in the rest of Europe) and women who work, on average, earn 20% less than men (Eurostat, 2010). Within years, only few policies have been adopted at national level to support women with young children, networks to help women navigate their careers and formal sponsorship programs to ensure professional development (www. womenomics.it).

With regard to the Italian healthcare sector, results from a survey administered to a sample of 1821 physicians of Padova city (Italy) in 2010 showed that 37,84% of the respondents declared to be not satisfied of the advancement in their career, and of these, 22% are women while 16% men (http://www.fnomceo.it). Whereas, results from another survey to a sample of 1549 Italian physician women belonging to the medical association in 2011 showed that 27% of the respondents declared to be discriminated in their work in general and 37.5% in their possibilities of reaching high job positions. 39% of the women reported that their ideas and suggestions were not taken in consideration by superiors and 80% reported that they have not been involved in any training opportunities. Finally, 4% of the sample declared to have received a physical abuse and only 61% was satisfied with their job (Ordine Provinciale di Roma dei Medici Chirurghi e degli Odontoiatri, 2011).

Given these premises, the present study intends to contribute to the researches on gender inequality at work by analyzing results from an organizational climate survey administered in 2010 to professionals of twelve Local Health Authorities (LHAs) of Tuscany region (Italy).

The purpose of this study is to determine whether organizational climate characteristics such as training opportunities, communication and information processing, managerial tools, organization structure and management and leadership style and overall job satisfaction are differently perceived across men and women at managerial and staff level within LHAs.

In particular, the study aims to test the following hypotheses:

- H1. “Male and female employees of Tuscan healthcare organizations differ significantly in terms of perceived organizational climate and job satisfaction.”

- H2. “Male and female employees of Tuscan healthcare organizations differ significantly in terms of perceived satisfaction in the relationship with their superiors in terms of communication, motivation, and support.”

This information can be used by organizations and human resource professionals to better understand possible barriers and discriminations perceived by women within the organization which can negatively affect their attitudes, behavior, and organizational commitment.

Data and methods

Organizational climate is a distinct construct concerned with the way organizational members perceive the work environment within that organization and its impact on their individual psychological wellbeing (Jones & James, 1979). This concept can be traced back to several studies, which have showed the role of the organizational climate survey to measure organizational characteristics perceived by employees and better understand those factors which contribute to a work environment (or climate) that is pleasant, and motivates all employees, regardless of their position, status and gender, to be committed and effective performers (Lewin et al., 1939; Koffka, 1935; Phillips, 1996).

Especially for those organizations requiring highly skilled employees, such as physicians in hospitals, a working environment which enhance the knowledge, skills, ability and motivation of employees have been demonstrated to have a greater impact on the performance of organization.

With regard to the Tuscan healthcare system, organizational climate as perceived by healthcare professionals has been always considered an important dimension to be constantly monitored through the Performance Evaluation System of the Tuscan healthcare. This system, developed in 2004 by MeS on behalf of Tuscany region, intends to constantly measure and monitor the quality of services provided and the capacity to meet citizens’ needs by healthcare organization in order to achieve better health and quality of life standards, on one side, and to preserve financial equilibrium, on the other (Nuti, 2008; Nuti et al., 2009; Nuti et al., 2012).

Since 2004, Tuscan healthcare top management and professionals are called to participate to the organizational climate survey which is carried out about once every two years within all Tuscan health organizations. This survey is based on two questionnaires, formulated in 2004 by MeS researchers (Pizzini & Furlan, 2012) following the international and national review on organizational climate.

Questionnaire “A” is directed to all managers with “management/budget” responsibilities (i.e., ward managers), and questionnaire “B”, to health employees. Both questionnaires were similar in size and items investigated.

Regarding to the procedures for compiling and sending the survey, mes lab provided the questionnaires on-line using the Computer Assisted Web Interviewing (CAWI) system: each employee had a login and password that allowed him/her access to the web platform for collecting data. Secure connection guaranteed the anonymity of responses and the safety of data transmitted.

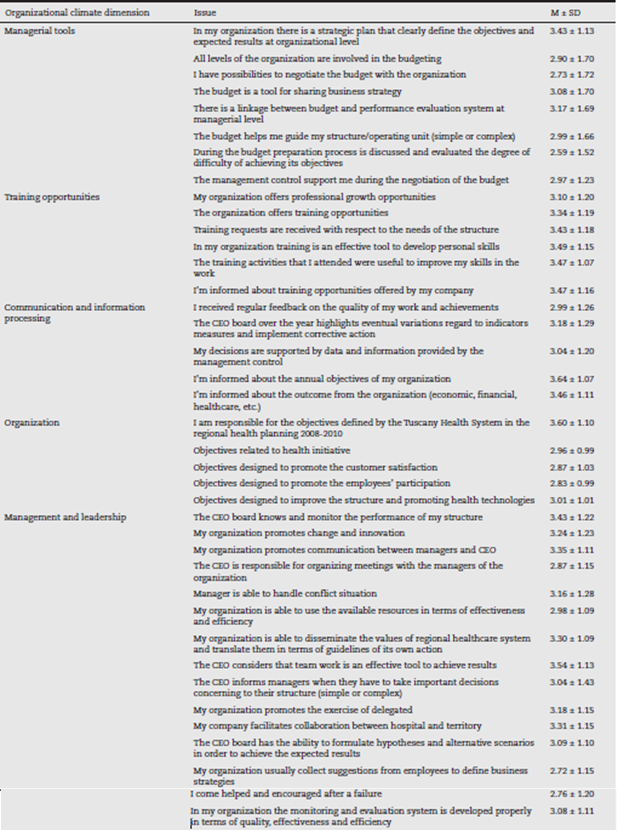

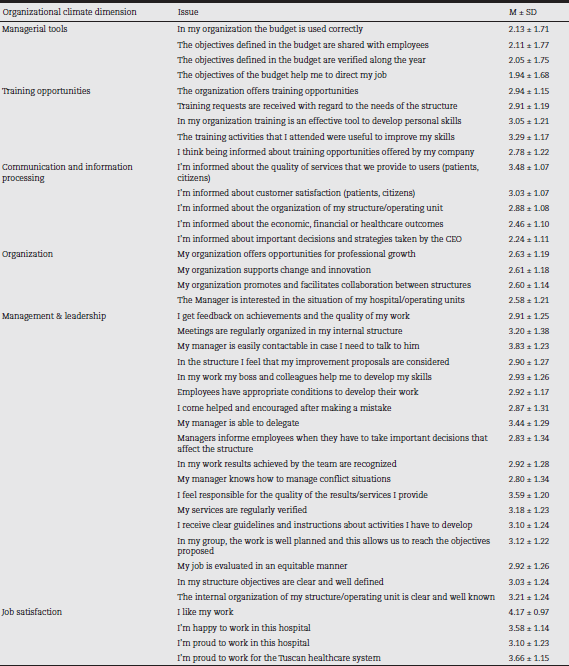

Independently from the questionnaire, all questions had a 5-point Likert scale format, ranging from 1 (extremely unsatisfied) to 5 (extremely satisfied). The analysis extracted information on the survey sample, job satisfaction and organizational climate dimensions, like communication and information processing, management and leadership style (ward managers and top management for employees and managers respectively), managerial tools (i.e., budget), company organization and training opportunities. Along years both questionnaires were tasted and validated and changes were made in order to assure the validity and reliability of the instrument.

With regard to 2010 survey data, we analyzed results from questionnaires A and B independently (851, 12,576 questionnaires). We calculated descriptive statistics and the means item scores were quiet low suggesting a general negative staff’s perception of the organizational climate.

Finally, we applied factor analysis to questionnaires A and B separately to obtain the perception of managers and employees in terms of the dimensions mentioned above. We performed descriptive statistics, factor analysis and two tailed test to examine gender differences in the LHAs. We used STATA software for statistical analyses (Version 12, Stata Corp.; College Station, TX).

Results

Respondents’ characteristics

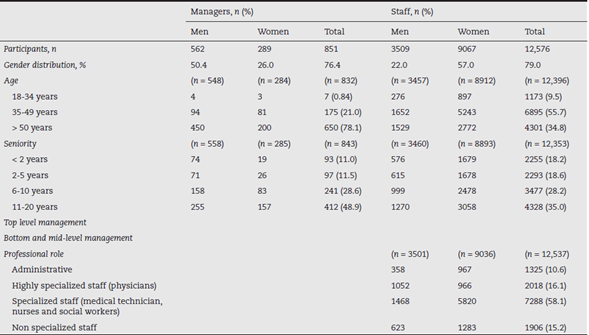

Table 3 shows descriptive statistics from gender point of view. The percentages of responders were 46% for managers and 33% for the staff. Most of the managers were male (66%), older than 50 years (54%) and had more than 20 years of working experience (30%). On the contrary, the majority of non-managerial staff was female (72%), in the age class of 35-49 (42%) and had 11-20 years of working experience (25%).

We analyzed 1113 of the 2407 managers (46%) and 15,942 of the 47,903 staff (33%); 851 managers (76%) and 12,576 staff (79%) completed the item about gender: from manager’s questionnaire, 562 (66%) were men and 289 (34%) were women; from staff, 3509 (28%) were men and 9067 (72%) were women.

Organizational climate dimensions

Factors were obtained using principal components factor analysis, with varimax rotation of the orthogonal axes, and in both cases the percentage of explained variance was about 65%. We calculated for each dimension Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient > .8, confirming the validity and internal consistency between items on the scale of each factor.

Applying factor analysis to the data, we obtained overall job satisfaction and five organizational climate dimensions:

Satisfaction with managerial tools was measured by eight items in the questionnaire A (α = .96) and four items in the questionnaire B (α = .96).

Satisfaction with training opportunities was measured by six items in the questionnaire A (α = .92) and five items in the questionnaire B (α = .90).

Satisfaction with communication and information processing was measured by five items in the questionnaires A and B (α = .90 and α = .86 respectively).

Satisfaction with the organization was measured by 15 items in the questionnaire A (α = .96) and four items in the questionnaire B (α = .90).

Satisfaction with management and leadership style was measured by five items in the questionnaire A (α = .88) and 18 items in the questionnaire B (α = .96).

Overall job satisfaction dimension was measure by four items in questionnaires A and B (α = .80 in both cases) and it is defined as a positive emotional response to the result of the work performed allowing the fulfillment of an individual’s value (Locke, 1984).

Gender differences in the perception of organizational climate factors

Phase two of the data analysis consists of studying differences between gender and professional roles groups. We used t-test to compare mean perceptions regarding the above mentioned dimensions across women and men in both managerial and staff position. We also analyzed separately key questions which are relevant to better explore gender inequalities at work. The probability level for all hypothesis tests was set at p ≤ .05.

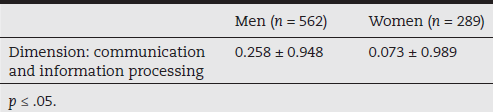

Gender differences at managerial level

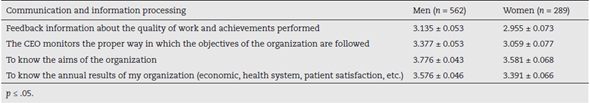

In the analysis of gender differences across high-level managerial positions, Table 4 shows that communication and information processing is the only significant dimension which has been differently perceived by men and women, with men being more likely to be satisfied then women. No statistically significant results were observed in the other climate dimensions.

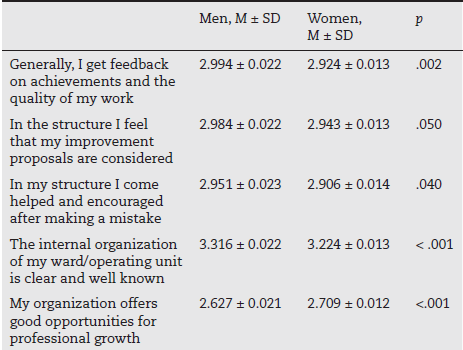

We further explored gender differences with respect to single questions regarding communication and information processing (Table 5).

Table 5: Distribution of male/female respondents by selected questions within dimension of communication and information processing at managerial level

Source: author

The statistically significant results suggest that there are differences in selected aspects concerning communication dimension between male and female managers. Results in Table 6 confirm that men are more satisfied with communication and information process. Men more than women tend to report higher scores to questions regarding the feedback and information received from the top management and the involvement and knowledge of both strategic long term objectives and the annual performance results (economic and financial performance, clinical outcomes, patient satisfaction, etc.).

Gender differences at staff level

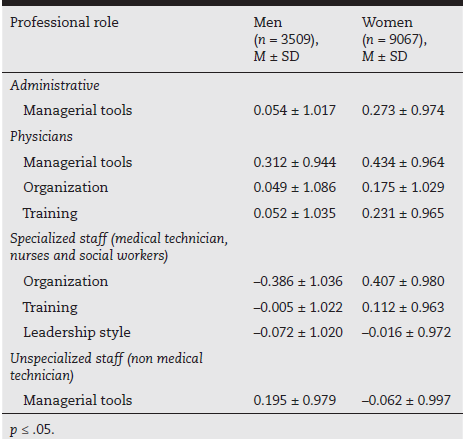

In this section we focus on the significant dimensions of organizational climate for healthcare staff according to the gender differences and professional role separate (Table 6). Results in table 6 shows that, in almost all the dimensions, highly specialized staff (physicians) is likely to be more satisfied than either specialized staff (medical technician, nurses and social workers) or unspecialized staff (non-medical technicians); this results are according with the literature (Carlucci, 2009; Wienand, 2007). Moreover, from gender point of view, women consistently report higher scores in the perceived organizational climate than men, and this is true across all dimensions and within all the professional roles, with exception of unspecialized roles where men declared to be more satisfied than women about managerial tools.

Gender differences at staff level within professional roles

-Administrative. Women in administrative position were more satisfied with managerial tools than their counterparts. No other statistically significant gender differences across dimensions were observed.

-Physicians. We found statistically significant gender differences in managerial tools, organization and training dimensions where women were significantly more likely to report satisfaction in these dimensions compared with men.

-Specialized staff (medical technicians, nurses and social workers). We found that women with respect to men were likely to be more satisfied with organization, training opportunities and leadership style dimensions.

-Unspecialized staff (non-medical technician). Managerial tools were the only significantly dimension perceived in the organizational climate by unspecialized staff. The aspects that pertain to the rewarding system had evaluated by women with the lowest scores compared with their counterparts.

Finally, Table 7 shows the significant dimensions of organizational climate analyzing gender differences at staff level within LHAs for specific questions reflecting possibilities of career advancement, motivation, support and feedbacks from the management.

When looking at single questions, women in general seem less satisfied than men, except for the opportunities for professional growth. Similarly to management positions, men, independently from the role, were significantly more likely to report satisfaction with the feedback on achievements, the quality of work, consideration and support received.

Conclusions

The first aim of the study was to investigate gender differences in the perception of organizational climate dimensions and job satisfaction across professional roles.

With regards to managerial positions, no gender differences were found in both job satisfaction and organizational climate dimensions, except for communication and information process, where men managers seemed more satisfied then women counterparts. On the contrary, when considering staff positions, women tend to report in general significantly higher scores than men.

This last result might be due to a real difference in the type of work performed among staff position. Clark (1997) argued that objectively, women’s jobs are worse than men’s, and those who expect less from working will be more satisfied with any given work. In this case, greater satisfaction in the perceived organizational climate may reflect women’s low expectations regarding to the work performed. Moreover, women, more than men, might also expect to have to accommodate to the needs of their family (Harriman, 1996; Spector, 1997).

Also, Eagly (1987) argued that gender differences in the work place are due to the bias of individuals to behave consistently with their social roles. For example, there are different expectations of behavior for social roles of doctor and nurse. There is a greater representation of men in the doctor’s role, and a greater representation of women in the nurse’s role. Therefore, the gender differences in the organizational climate between men and women in these roles can be a result of differences in the distribution of doctors and nurses.

With regard to the second hypothesis of the study, gender differences were found in the perception of selected aspects such as:

The level of communication of the organizational planning and strategic objectives between managers and CEOs.

The level of communication of the organizational unit objectives and work program between staff members and managers.

Communication and ongoing feedbacks between staff members and managers on the quality of the work.

The level of promotion and motivation staff members own professional development goals.

All of these aspects are strictly related on the way one’s supervisor handles his workers in terms of recognition one gets from doing the job, communication of organization/ wards objectives and strategies, recognition of individual contribute. Our analysis shows that with respect to these aspects, males are likely to be more satisfied than their counterparts. This is true across all the professional positions within the organization.

Even in a female dominated profession such as healthcare, the number of women in supervising positions is less in comparison with men (LaPierre, 2012; Wiggins, 1996; Walsh & Borkowski, 1995). This masculine environment in supervisory positions is likely to promote asymmetries that contribute to different gender perceptions and behaviors in the organization. Females in the Tuscan healthcare environment may face challenges in the supervision-human relations aspects which in part maybe due to gender stereotypes that exist between men and women in these supervisory relationships. Women are often considered by men as less career-orientated, more committed to the family than their jobs, less motivated by organizational rewards than their male counterparts, and they often they have to work harder to demonstrate their competence.

On the other hand, women would like to be more involved in the communication processes and for them is most important to know and to share with the management staff the organizational goals. Indeed, males have been demonstrated to be dominant, unemotional and more task-oriented while females tend to be more emotional, compassionate, emphatic and supportive, and more interpersonally oriented (Eagly, 2001).

Burke et al. (1998) showed that women who supervise may be more sensitive to the needs of women on their staffs, better able to develop closer relationships with them, and more willing to invest in this relationship than male supervisors. As a consequence, one might expect that men in managerial position would interact differently with those they supervise if men or women, supporting the fact findings that females tend to be less satisfied than male in some aspects related to communication, information, and interaction with supervisors who are for the majority males.

The results of the present study support the hypothesis that there are gender difference in how the organizational climate is perceived by managers and employees in Tuscan healthcare organizations. The analysis showed that the Tuscan organizational climate questionnaire is a reliable instrument used as a measurement tool for evaluating working conditions and determining the different factors which satisfies and motivates employees in the healthcare sector.

This study shows that there are gender differences in how individuals experience satisfaction within work environment, especially across all professional roles within healthcare staff. In terms of particular aspects of the job related, it was found that males rated higher than females the interaction with their supervisors.

Women want more from their leaders: they want to participate, to share responsibilities by adopting a team working approach. They tend to believe much more than men in positive effects of training activities and personnel involvement in the organizational performance. Men with management responsibilities in the health sector should dedicate more time to their staff, especially to women working in their team, in order to facilitate their involvement in the improvement process, and to guarantying space and development to their contribution.

The use of an organizational climate survey can help management to identify the critical points in the factor dimensions and communicate more effectively within the structures improving the effectiveness of total quality management programmers. In fact, a valid internal climate survey can be a useful tool in supporting the management to avoid perceptual discrepancy and tailor a motivational strategy that is specific to the employee’s individual needs and aspirations.

Moreover, in order to assure its effectiveness, it is important to share and discuss the results of the internal climate survey with all the professionals, being this the most important prerequisite to support the organizational changes and it is what the Tuscan health managers are used to do not only with regards to the internal climate results, but also to all the performance measures.

Two are the principal limitations of the study. The first is that the sample is not necessarily representative of healthcare professionals from other geographic context. The second is that due to privacy reasons some respondents failed to report their gender introducing possible selection biases in the results. Further, there are many other factors that can be considered to determine employees’ satisfaction which can be added to expand the study in future.