Introduction

This paper analyzes, through a qualitative research, how the discourse of entrepreneurship is constructed from a gender perspective, highlighting the differences between men and women who identify scenarios, elements and conditions to develop enterprise business ideas or decide to bet to generate their own employment, risking and organizing his own way of working. The objective of the work is distinguishing what psychobiological, cultural and family aspects facilitate or impede, by gender, perceive opportunities to undertake and act accordingly. At the same time, it will consider the jurisdictional aspect, because on one hand, competition is associated with tangible, observable aspects and directly measurable: behaviors that have a beneficial result; on the other, it is established that there is competition there must be an environment where developing it, the workplace (Olaz & Brändle, 2013: 12).

The entrepreneur term derives from the word undertake, from the Latin in (on) prendere (take, take), and is related to the French word entrepreneur, emerging in the early 16th century to refer to the adventurous or pioneers. In the early 18th century in France the meaning of the term extends to builders of roads, bridges and architects. And it will be from the second half of the 18th century when it will be related to people who facing uncertainty initiates a new business or business project, to innovative entrepreneurs. CEDEFOP (1991: 10) points out that when speaking about selfemployment or entrepreneurship a reference is made to those “persons who organize, direct and assume risks of their own business or productive activity because they understand they have novelties to offer or because there is a production space where they can compete successfully.” Meanwhile, Alonso Ramos (2005: 165) defines self-employment as an alternative access to a professional or business activity, appropriate for those workers with a dynamic profile and willingness to take risks that enables them to create their own job prospects stability herein.

The implementation of a project of self-employment or entrepreneurship requires to articulate three kinds of skills, without which it will be difficult to achieve success: specific vocational skills, entrepreneurial skills and business skills. Among the entrepreneurial skills, we find the capacity of initiative, creative skills in innovation, achievement motivation, self-confidence and self-esteem, the ability of planning and organizing, positive vision of the future and realistic, communication and generation of supporting networks, constructive acceptance dealing with uncertainty, flexibility, self-discipline, capacity for hard work, commitment, determination, responsibility, autonomy and self-sufficiency (Sánchez Cañizares & Fuentes García, 2013).

Gender differences in the discourse of entrepreneurship

In the speech of entrepreneurship it is clearly distinguishable the perception in women of a minor entrepreneurial initiative, as well as gender differences in the attributes associated with higher odds of undertaking an entrepreneurial project.

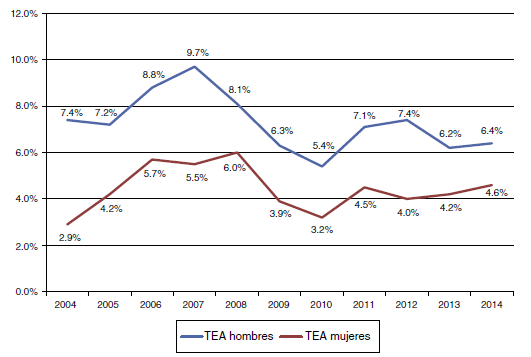

The initial assessment clearly corresponds to the reality of the empirical data. According Congregado et al. (2008: 30), the “group of entrepreneurs is mostly made up of men (. . .); in 2006 more than 70% are, compared with 29.6% of women” and, although the difference between men and women when undertaking is decreasing in Spain GEM 2014 report also notes that “approximately six out of ten entrepreneurs according to the TEA index in 2014 were men” (Fig. 1). However, the women tend to have a slightly higher education than male entrepreneurs, as was clear from the data of Spain GEM 2012 Report, which placed the percentage of entrepreneurs with university level in 38.4% vs. 32.3% of male entrepreneurs with this level of education.

Source: Based on data from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, GEM Report Spain, 2013 and 2014.

Fig. 1 Evolution TEA rate by gender in Spain for the period 2004-2014.

The perception that the differences are being minors over the years appears clearly in this speech. So one of the interviewees says:

“I think those differences are getting shorter over the years, that is, a few years ago if there were differences, women had more problems when undertaking than man” (E1-Women); and another says that: “it has come a long way already, but we still have a long way to go” (E5-Women).

However, a part of the discourse maintains that the differences between the younger people have disappeared and when asked if there are differences between men and women when undertaking, one of the interviewees replied: “I believe that in younger people for absolutely nothing. As far as I’m concerned absolutely nothing” (E4-Women).

On the other hand, as noted by another interviewee, “women, when undertaken, keep thinking in different business to those of the men” (E2-Women).

This statement coincides with that shown in different studies (Clark & Janes, 1992), regarding companies boosted by women have a lower average size than those promoted by men and an increased focus on services related to traditional activities, mainly trade, catering and personal services (Rodríguez Gutiérrez & Santos Cumplido, 2008: 120). In this sense, several respondents pronounced

“perhaps in more industrial sectors is more difficult to see women in most services sectors is seen more women” (E10-Man); “On the trade issue, shops . . . yes there are more women than in the industry” (E2-Women).

Another of respondents, meanwhile, said

“the major part of the women entrepreneurship is formed by family business” (E5-Women).

The different investigations conducted so far (Audretsch & Fritsch, 1994; Fernández & Junquera, 2001; Keeble & Walker, 1994) conclude that there are two groups of determinant factors of entrepreneurial activity: personal factors relating to the entrepreneur person and the factors related to the environment.

Psychobiological, cultural and familiar aspects as determinants of entrepreneurship

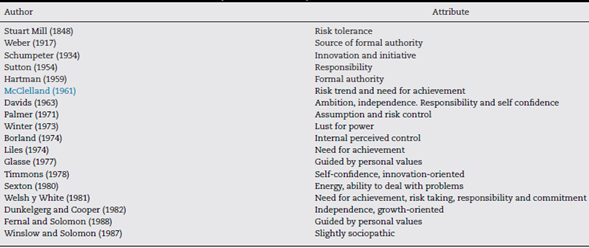

Christersen made in 1994, through a historical journey that ended in 1987, a selection of the main attributes of entrepreneurs in which, as can be seen (Table 1), different authors have been emphasizing over time in multiple attributes, but without analyzing the differences that may occur between men and women regarding those same attributes.

Table 1 Main attributes of the entrepreneur (Christersen, 1994).

Source: Alonso Nuez and Galve Górriz (2008: 13)

Throughout our investigation, to see if there are differences between men and women entrepreneurship, we have reviewed the psychobiological, cultural and family aspects and has raised them to the respondents if they believe that there are differences in undertaking because of gender and what those differences are. As for the psychobiological factors alluded to those aspects or elements of internal type, that is to say, innate (psychological and biological) that can cause differences between men and women entrepreneurship. Most are related to the skills and refer to intuition and insight, reflection, emotion, creativity and imagination, language skills and brain function. As for the cultural aspects, that is, related to the patriarchal culture and the traditional division of spaces, professions, roles, etc., that causes the differences between men and women in entrepreneurship. It also refers, on the one hand, to those features that the traditional division of roles assigned to women by their gender, and secondly, the type of social context (more conservative or more modern) in which the person is who wants to undertake. Here referred to three aspects: professional and masculinized environments, functions and social characteristics that the environment attributes to the woman for her condition and pressure of the environment/social context type (conservative vs. modern). Regarding family issues, here it referred to family-related aspects: presence of children in the household, marital status of the person, support/involvement of the sentimental pair or the family environment, difficulties regarding reconciliation, housework, etc., that can create differences between men and women entrepreneurship, damaging the latter. At this point attention is placed to the reconciliation variable and on the need for support from family.

Psychobiological aspects

In all cultures there are a number of attributes associated with gender stereotypes that reproduce through the process of socialization, and in every society there are a number of instrumental traits associated more to the male (autonomy, ambition, rationality guidance to success, self-reliance, aggressiveness, etc.) and other traits mainly associated with femininity (kindness, respect, empathy, prudence, expressiveness, weakness, tenderness, instability, concern for others, etc.) (López-Sáez, Morales, & Lisbona, 2008).

Several authors (Crecente Romero, 2011: 34; Marulanda Valencia, Montoya Restrepo, & Vélez Restrepo, 2014: 211) agree that the American psychologist David C. McClelland, in his study of graduates from Wesleyan University, was a precursor in the analysis of the personal motivations that predispose people to start a business McClelland (1961). For this author, the need for achievement is the main attribute that makes an individual to become an entrepreneur. Since then, this factor has been studied as one of the main characteristics of entrepreneurs and various studies have shown the importance of it (Barba Sánchez & Atienza Sahuquillo, 2011). But McClelland (1961) also pointed out other features to potential entrepreneurs, such as originality and innovation, a moderate risk aversion, accept its responsibilities, the perception of the results of their actions and long-term planning. But his main contributions was to point out that these factors were not innate in the individual, but are developed through educational systems and cultural and social values found in society. Other authors (Boydston, Hopper, & Wright, 2000; Davidsson, 1989) agreed to associate with the capacity to undertake with attributes such as self-confidence, optimism, creativity and autonomy. Finally, some researchers (Begley & Boyd, 1987; Cooper & Dunkelberg, 1986; Kaufmann, Welsh, & Bushmarin, 1995; Mueller & Thomas, 2001; Callado et al., 2006) have used the concept of “locus of control” developed by Julian Rotter from the publication in 1954 of his book Social learning and clinical psychology. Bonnett and Furnham (1991), in a study on young entrepreneurs, found that manifested themselves more “locul internal control”, understood as the perception that a person has that the events taking place around them can be influenced by their own actions, that is to say, the individual influences his environment, which leads to positively assess the ability, effort and personal responsibility.

Meanwhile, other authors, like Amit, Glosten, and Muller (1993) indicate that entrepreneurship does not seem to be related to particular characteristics of personality, but rather with a form of behavior that can be changed and learned. In the same way are pronounced Rodriguez and Santos (2008: 120) when they say that “there seems to be no such agreement regarding the possible existence or not of psychological character traits differentials between men and women entrepreneurs” that might explain the differences in the characteristics of their companies.

However, authors like Álvarez, Noguera, and Urbano (2012: 49), verified in their studies that “the perception of skills to undertake increases the probability of being an entrepreneur to 9.09 times for women, compared to 7.99 times for the men”.

Currently, the discourse of entrepreneurship seems to follow a fairly widespread and politically correct opinion, in the sense of begin denying the existence of significant differences of psychobiological character between women and men, and then go sliding, as a possibility, some:

“The woman is perhaps more accurate on an intuitive level than man (. . .) Men are more analytical, more oriented to the effectiveness, results, and that’s fine, i do not say no. but in an uncertain world that’s fine as a complement, but intuition is much more effective” (E3-Women).

“They may have much more tenacity the women (. . .), are much tougher, much more constant when carrying out an idea, a project or goal” (E7-MAN).

“When undertaking is not to be feminist but the women do have a way . . . we are more creative (. . .) in general women are more empathetic” (E4-Women)

“In women I see that may have a greater capacity to take diverse subjects at the same time” (E8-MAN).

“Women are more emotional tad (. . .) we are more secure, more cautious, more thoughtful, have the long-term vision, than man does not have, we are more constant than they, more efficient, more disciplined and sure of ourselves. all these aspects men do not usually have” (E5-Women).

“Women have generally more social sensitivity” (E10-MAN).

Thus, speech is clear that women would be more intuitive, tenacious, creative, cautious, emotional, reflective, self-confident, with greater empathy, more socially sensitive, more long-term vision and a mayor capacity to develop several themes as well as men. In short, it seems that in the discourse on entrepreneurship, though begins to glimpse some restraint when it comes to use gender stereotypes, are still using the attributes of the masculine and the feminine as a resource to justify differences, consciously or unconsciously, often they seem to be considered as natural.

Cultural aspects

The Spanish family tradition, patriarchal and Catholic base, has tended to provide a formation to male children to enter the labor market, while it has reserved a family and domestic role to women, basically linked to the figure of marriage (Escribá, 2006: 148). Certainly, this way of conceiving the children’s education it is not a widespread reality in our country for a while, but it is likely that certain features of that tradition are still present, albeit in an unconscious way. The family, as well as influencing the educational level at which an individual arrives, also involved in the processes of integration, that is, in the job search. Parents help to find work to their children through their circle of relationships (family, friends, colleagues of the companies where they work) and out of this circle can be difficult if you don’t have the sufficient motivation and adequate qualification which allows to break social networks of parents (Gil Rodríguez, 2005: 366-367; León Santana, 2000: 125). Thus, we find some statements that these difficulties are evident:

“I can assure you that everyone and my family told me i was crazy, that i had lost the screws” (e3-women). education has a very important role in overcoming these family influences that reproduce gender stereotypes: “formation is important (and to be well-connected” (e1-women); “then also, the education influences that still have the girls who we have educated” (e2-women). furthermore, the speech also overlook the difficulties that women have to be formed, often by having to harmonize professional duties with family: “it’s hard for women to go out, we find it difficult to form us, at meetings you only see men because the woman does not want to be there by whatever, we do not have time . . .” (E1-women).

The whole discourse seems to corroborate the remaining differences in the formation and the professional experience of men and women, which in different studies have confirmed to verify that men tend to reach high skills in a wide variety of business skills and experience in sectors such as manufacturing, finance or technical areas, while most women tend to have management experience, usually more related to services such as education, secretarial work, or retail areas (García Tabuenca, Crespo Espert, & Pablo Martí, 2009: 8-18).

Castilblanco Moreno (2013: 61) and Kargwell (2012) argue that differences in the type of business are attributable to cultural barriers: women tend to work in home-related activities because they are socially better accepted. While men are targeted to study math and science, the women make it toward the humanities, which usually do not have adequate training in science that would help them to undertake businesses that require technical skills.

When looking for professional careers, or choosing a profession, still remain socially stereotypes about what is considered proper or improper for women and men, for the fact of being. Thus, in the speech we find:

“There are professions that women do not have access because they are men prototype throughout life, which are things that . . . as the topics of engineering . . . women undertake fewer there. Are there any women who can put up a mechanical workshop? . . . No . . . And other sectors that are needed, I refer to undertake . . . A plumbing workshop . . . all that kind of stuff are masculinized” (E2-Women).

Even some interviewed describes the creation of a company as “entering a male world, where competition is basically male. If you don’t know how to move there . . .” (E3-Women).

Moriano (2005: 15-16) states that “there are certain aspects of the social environment, such as family history, previous experience or learning, system of values, and societal guidance, among others, that promote or inhibit the emergence of entrepreneurs . . . so there are rather something like ecological niches for entrepreneurs, or, if preferred, spatiotemporal frameworks where it is expected to arise entrepreneurs”. In the discourse on entrepreneurship it is found that on numerous occasions the social and family environment is associated with the fact of the creation of companies by women. Thus, it is noted that in certain spatial areas is easier to undertake

“in rural areas women take longer to undertake than in urban areas” (E2-Women) or “women in cities have fewer problems than in municipalities. In municipalities the woman still have a little more trouble that man because that environment is not very conducive” (E1-Women); or family experiences greatly condition entrepreneurial behavior: “I have lived the family business, and was very clear i had to follow because i have not experienced anything else and had no choice and i also enjoy it” (E5-Women).

In short, there are some social aspects that explain the willingness to undertake and that may be the motivation for entrepreneurial behavior so you have to keep in mind, as Ortiz and Millan (2011: 234) point out “the importance of social factors in the gestation of entrepreneurial activity”.

Family aspects

In early studies, conducted in USA and UK, it was noted that the motivations that led women to entrepreneurship was the search for independence, the need to control their future and a greater labor flexibility that would reconcile professional development and dedication to the family (Brush, 1990; Carter, Anderson, & Shaw, 2001). However, one respondent noted that to be enterprising “the main difficulty i see it is that the woman has to reconcile family and working life” (E2-Women).

Women, especially those belonging to the group of modern entrepreneurs, seem to value more than men family support in developing their business. Although women are getting ever more to occupy new spaces in the professional sphere is not occurring with the necessary speed an increase in the male involvement in domestic tasks. Very often women have to limit their job options to the needs of family care (García Tabuenca et al., 2009: 2-7). Thus, in the speech phrases like the following appears:

“the preparation right now that women have it is like boys or better in some cases, but nevertheless, when undertaking the woman thinks of her role as a woman, it does not have the same freedom as a man. always think in a company that can harmonize with his profession and her house” (E2-Women).

As claim by Alvarez et al. (2012: 46) the “Actual studies show the preference of women entrepreneurs to the use of collaborative networks, establishing the existence of differences in use between women and men in the process of creating a company and seeing greater ‘use’ of the family by women entrepreneurs”. Several authors (Baughn, Chua, & Neupert, 2006; Langowitz & Minniti, 2007) have analyzed in their works that in those societies where women’s role is very attached to family responsibilities, it appears less appreciated entrepreneurial activity of the women. Similarly, William (2004), in his article on the determinants of success in self-employment in terms of time spent on childcare, using data from the Household Panel of the European Union from 1994 to 1999, concludes that the concern and dedication to the children, significantly reduces the duration and success of businesses and entrepreneurship. In the speech frequently appear phrases like

“you have a marriage where both are working, because when asking for leave or permission to take the child to the doctor, dad never asks permission, is always the mother (. . .) If a child gets ill you call the mother because it’s the first phone that comes on the agenda. So what happens, the woman there will always have an obstacle and while that exists, the woman will always be undervalued at work” (E2-Women).

In fact, Alvarez et al. (2012: 50) have shown empirically that being female and have family responsibilities reduced by 33.1% the probability of being entrepreneurial, while in the case of men, this reduction is only 2.4%.

Castilblanco Moreno (2013: 61) refers to the study of Kargwell (2012), done on gender differences in entrepreneurs in the UAE, in which “part of studying the role of women as socially constructed and confined to home care, taking responsibility for their children and husbands. And with this element, is the first difference between the behaviors of female entrepreneurs and male entrepreneurs: The cultural barrier prevents the population conceive women as able to run their own businesses and inhibits them to start business projects. Also, this feature contributes to the social commitment of women and men to their business. 45.6% of men assumes that in family matters are not part of their responsibilities because they have culturally been given the role of “food providers.” Thus, this division of labor between genders generates that women have to divide their time between their homes and businesses spending between 1 and 4 h to their companies (69.8%) in counterpart with the men, who spend between 5 and 8 h a day to their business (85.9%).

“This situation means additional effort and many sacrifices on the part of women entrepreneurs, AS one respondent notes,” women entrepreneurs (. . .)

Certainly have to sacrifice some of their personal and family life to undertake because the entrepreneur does not have schedules, have to devote most of his time to the project that is being developed (. . .) AT the end should have A help, (. ..) A very strong support in the family environment” (E6-Man).

Conclusions

So far, numerous researches have been raised to answer the question of what it is that predisposes a person to be entrepreneurial, to promote the development of entrepreneurial business ideas. There is no single answer to this question and, also, there seems to be differential characteristics between male and female entrepreneur ship, suggesting the need to analyze the particularities of entrepreneurship from a gender perspective.

In the speech of entrepreneurship differences between men and women are recognized. On the one hand, women are perceived in less entrepreneurial initiative and, secondly, gender differences in associated attributes most likely to undertake an entrepreneurial project are observed.

Throughout our research we have reviewed the psychobiological, cultural and family aspects from which it comes to explaining the differences in entrepreneurship in terms of gender.

When we speak of psychobiological factors we refer to those aspects or elements of internal or innate kind, of psychological or biological character, that intervene in the differences in men and women in relation to entrepreneurship. Although there is controversy about the existence of such factors, from the analyzed speech an impression that begins as restrained by denying the existence of significant differences of psychobiological character between women and men, then gradually introduce, as a possibility, some: women, compared to men, would be more intuitive, tenacious, creative, cautious, emotional, reflective, self-confident, more empathy, more socially sensitive, with more long-term vision and greater ability to develop various topics. In short, the speech still use attributes of the masculine and the feminine as a resource to justify differences.

In relation to cultural aspects, that is to say, those related to the patriarchal culture and the traditional division of spaces, professions, roles, etc., that cause the differences between men and women in entrepreneurship, in the speech the persistence of current social stereotypes about what is considered proper or improper for women and men (education, choice of profession, etc.) is observed, there being some aspects of the social environment (family background, experience or previous learning, etc.) that would explain the willingness to undertake and that could motivate entrepreneurial behavior.

With regard to family aspects, it points to aspects related to family and essentially to the variable conciliation and the need for support from the family. In the analyzed speech is distinguished that, although women are getting ever more to occupy new spaces in the professional sphere, is not occurring at the same rate an increase in the involvement of men in domestic tasks, what it makes women regularly have to circumscribe their options to take care of the family needs, and it involves an extra effort for them and many privations.

Finally, note that this research shows that the incorporation of the analysis of entrepreneurship from a gender perspective, must serve to implementing policies and specificaction plans to encourage female entrepreneurship.