Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Revista Finanzas y Política Económica

versão impressa ISSN 2248-6046

Finanz. polit. econ. vol.5 no.2 Bogotá jul./dez. 2013

ARTÍCULO DE INVESTIGACIÓN

DIRECT AND INDIRECT IMPACT OF FEDERAL TRANSFER TO INDIVIDUALS AND TO THE GOVERNMENT OF PUERTO RICO1

IMPACTO DIRECTO E INDIRECTO DE LAS TRANSFERENCIAS FEDERALES A LOS INDIVIDUOS Y AL GOBIERNO DE PUERTO RICO

IMPACTO DIRETO E INDIRETO DAS TRANSFERÊNCIAS FEDERAIS AOS INDIVÍDUOS E AO GOVERNO DE PORTO RICO

ÁNGEL LUIS RUIZ MERCADOa

INTERAMERICAN UNIVERSITY OF PUERTO RICO, SAN JOSÉ DE PUERTO RICO

a Ph.D., and M.A. in Economics, Professor of Economics in the Doctoral Program, Faculty of Business Administration, Interamerican University of Puerto Rico. San José de Puerto Rico Correo electrónico: angelruiz@onelinkpr.net

Recibido: 18 de mayo de 2013 Concepto de evaluación: 10 de junio de 2013 Aprobado: 5 de septiembre de 2013

ABSTRACT

The Puerto Rico Planning Board classifies individual transfer payments into two categories: "earned transfers" and "granted" transfers. The purpose of this work is to estimate the direct and indirect economic effects of federal and other transfer payments to Puerto Rico using two input-output models and two vectors of employment and income coefficients base on tables for years 1992 and 2002. The economic impacts were estimated for three economic indicators namely, gross output, direct and indirect employment and direct and indirect wage income. The results presented in this work shows that the argument that Puerto Ricans enjoy relatively generous income supplements and retirement benefits without imposing heavy tax burdens on highly compensated workers failed to distinguish that most of the transfer payments to individuals were in the category of earned transfers. It is doubtful that this type of transfer "impose heavy tax burdens" to American taxpayers. Since we are an open economy most of the income generated by transfer to individuals is spent of goods and services a substantial amount of which comes from United States. It is also doubtful that earned transfer to individuals (especially transfers in the form of pensions and payments to veterans) have any significant impact on the labor force participation rate or the incentives to work.

Keywords: Puerto Rico, earned transfers, granted transfers, flow of funds, input-output analysis, direct and indirect impacts, incentives to work, low labor force participation rate.

JEL: H77, O11, O19, O20, R11

RESUMEN

La Junta de Planificación de Puerto Rico clasifica las transferencias individuales en dos categorías: "transferencias devengadas" y "transferencias concedidas". El propósito de este trabajo es estimar los efectos económicos directos e indirectos de las transferencias federales y de otros tipos a Puerto Rico por medio de dos modelos de insumo-producto y dos vectores con base en los coeficientes empleo e ingreso de las tablas para los años 1992 y 2002. Los efectos económicos se estimaron para tres indicadores económicos a saber, la producción bruta, el empleo directo e indirecto y los salarios directos e indirectos. Los resultados presentados en este trabajo muestran que el argumento de que los puertorriqueños disfrutan de complementos de renta relativamente generosos y jubilaciones, sin imponer pesadas cargas impositivas sobre los trabajadores altamente remunerados, no era diferente a la mayoría de los pagos de transferencias a las personas que se encontraban en la categoría de transferencias devengadas. Es dudoso que este tipo de transferencias "pesadas cargas impositivas" sean impuestas a los contribuyentes estadounidenses. Ya que somos una economía abierta, la mayor parte de los ingresos generados por las transferencias que las personas gastan en bienes y servicios, gran cantidad proviene de Estados Unidos. También es dudoso que las transferencias devengadas de las personas (especialmente las transferencias por concepto de pensiones y los pagos a los veteranos) tuvieron un impacto significativo en la tasa de participación de la fuerza de trabajo o en los incentivos al trabajo.

Palabras clave: Puerto Rico, transferencias devengadas, transferencias concedidas, flujo de fondos, el análisis de insumo-producto, los impactos directos e indirectos, los incentivos al trabajo, la baja tasa de participación en la fuerza laboral.

RESUMO

O Conselho de Planejamento de Porto Rico classifica as transferências individuais em duas categorias: "transferências adquiridas" e "transferências concedidas". O propósito deste trabalho é estimar os efeitos econômicos diretos e indiretos das transferências federais e de outros tipos a Porto Rico por meio de modelos de insumo- produto e dos vetores com base nos coeficientes emprego e ingresso das tabelas para os anos 1992 e 2002. Os efeitos econômicos se estimaram para três indicadores econômicos: a produção bruta, o emprego direto e indireto, e os salários diretos e indiretos. Os resultados apresentados neste trabalho mostram que o argumento de que os porto-riquenhos gozam de complementos de renda relativamente generosos e aposentadorias, sem impor pesadas cargas impositivas sobre os trabalhadores altamente remunerados não era diferente à maioria dos pagamentos de transferências às pessoas que se encontravam na categoria de transferências adquiridas. É duvidoso que esse tipo de transferências "pesadas cargas impositivas" sejam impostas aos contribuintes estado-unidenses. Por sermos uma economia aberta, a maior parte dos ingressos gerados pelas transferências que as pessoas gastam em bens e serviços, grande quantidade provém dos Estados Unidos. Também é duvidoso que as transferências adquiridas das pessoas (especialmente as transferências por conceito de aposentadoria e pagamentos aos aposentados) tiveram um impacto significativo na taxa de participação da força de trabalho ou nos incentivos ao trabalho.

Palavras-chave: Porto Rico, transferências adquiridas, transferências concedidas, fluxo de fundos, análise input-output, impactos diretos e indiretos, incentivos ao trabalho, baixa taxa de participação na força laboral.

INTRODUCCIÓN

In a relatively recent article Gary Burtless and Orlando Sotomayor (2006) argue that "because Puerto Rico is the recipient of substantial net transfers from the mainland government, taxpayers on the island do not have to pay for all the government benefits received by the island residents. Low income Puerto Ricans enjoy relatively generous (emphasis of mine) income supplements and retirement benefits without imposing heavy tax burdens on highly compensated workers". They go ahead to analyze the impact of transfer payments on labor force participation rates and the incentive to work. In the analysis they failed to distinguish between granted and earned transfers. When analyzing both types of transfers the federal government program of transfers to Puerto Rico does not seem so "generous". The starting point when analyzing transfer payments is to separate both types of transfers.

During 2011, Puerto Rico received a total of $16,854.4 million in gross transfer payments from the federal and state governments and other non-residents (Table 1). Federal transfer payments were divided as follows: transfers to individuals, $15,580.0 million; subsidies to industries, $213.8 million; transfers received from state governments, $21.1 million; and transfer from other non-residents, $1,039.5 million. Payments to the federal government and to non-residents of $3,613.0 million have to be deducted from the gross amount, however, leaving a net balance of transfer of $13,241.4 million. In addition to federal transfers to individuals, the Government of Puerto Rico received a total of $5,088.6 million for joint projects and operational expenses for a total net transfer into the Puerto Rican economy in 2011 of $18,330.0 millions. This amount was equal to 18,6 % of 2011 GDP compared with 13,2 % of GDP in 1992.

The Puerto Rico Planning Board classifies individual transfer payments into two categories: "earned transfers" and "granted" transfers (table 2). The first category is defined as those transfers received by persons and government for previously rendered services or for previous payments to the federal government, like for instance, veterans and social security payments, respectively. The second category of transfers are those given unilaterally to Puerto Ricans. They cannot be related, at least directly, to previously rendered services or payments. During fiscal year 2011 gross earned transfers amounted to $10,910.4 millions compared to $4,669.5 millions in gross granted (or unilateral transfers) to individuals and $5,088.6 to government. The major component of earned transfers is social security payments which amounted to $7,081.6 during fiscal year 2011 (64,1 % of all earned transfers to individuals). Nutritional assistance is the major component of granted transfers, amounting to $1,766.8 millions, or 37,8 % of granted transfers to individuals during fiscal year 2011. Adding payments to government and deducting payments made by Puerto Ricans to the federal government, net transfers received in 2011 amounted to $17,528.1 millions. It is important to emphasize that any analysis of transfer payments to the island should start by using net amounts, otherwise the analysis will be biased. Since we are dealing with two economies, the flows from both should be taken into account. Table 1 below offers a detailed account of earned and granted transfer payments to individuals for fiscal years 1992 and 2011.

As mentioned before, besides transfers to individuals, residents and government of Puerto Rico receive other transfers and grants (in the case of government). During fiscal year 2011 these two categories of transfers amounted to $5,302.3 million (after deductions a net amount of $4,989.7). Table 2 shows other transfer payment for years 1992 and 2011 and table 3 shows a summary of federal grants to the government of Puerto Rico (Commonwealth government, Public enterprises and Municipal governments).

In the next section the input output model together with vectors of employment and income coefficients is used to estimate the impact of transfer payments in the economy of Puerto Rico.

The economic impacts will be shown for three economic indicators namely gross output, direct and indirect employment and direct and indirect wage income.

METHODOLOGY AND MODEL

Methodology: transfers to individuals

The Leontief's open input output model data requirements consist of an industry-by-industry transaction matrix (in our case 93 by 93 for years1992 and 2002), a rectangular matrix of value added and a rectangular matrix of final demand. To estimate vectors of direct and indirect employment and income, we also need employment and income coefficients. The exogenous vectors of the model are the different components of final demand matrix2. Therefore, our first task was to transform data of transfer payments into final demand vectors. Earned and granted transfers to individuals were distributed according to the percentage (weights) of each component of consumption vector in total consumption. The hypothesis behind this procedure was that individuals spend transfers received on consumption of goods and services. However, some of the transfers were allocated to specific industries (not distributed proportionally). For instance, scholarships were assigned to the educational service industry. We used the consumption vectors of 1992 and 2002 as weights. Grants to government were allocated to government expenditures vector of the final demand matrix (the components of final demand matrix are the column vectors of consumption, Investment, Government consumption expenditures and the external sector) . Other miscellaneous transfers were allocated using proportions derived from consumption vector and government consumption vector (in the case of transfer to industries which figures consist mostly of the Job Training Partnership Act JTPA).

The figures for transfers were net of payments to the federal government and others (receipts minus payments). Final demand estimates and results for year 1992 were expressed in current prices since the input matrix available was for that year. Figures for 2011 were deflated and expressed in 2002 prices using the Gross domestic Product the implicit price deflator by industry (By SIC). The dimension of the matrices used were of 93 by 93 sector3. The benchmark table for year 2002 was updated to 1911 using RAS method.4

Data Sources model

Data Sources

The Input-Output Tables for years 1992 and 2002 were supplied bay the Puerto Rico Planning Board. The table for 2011 was estimated by the author using the RAS method. Employment by industrial sector (to estimate employment coefficients) were supplied by the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico Department of Labor and Human Resources.

Model

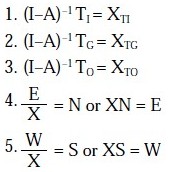

The following equations in matrix and vector notation were used to estimate direct and indirect effects of transfer payments on gross interindustry output, employment and income. The model was run for both 1992 and 2006 for the three categories of transfer payments.

Where,

(I-A)-1 is a 93 by 93 direct and indirect coefficient input output matrix for year 1992 (better known as Leontief's inverse.

TI = transfer payments to individuals (final demand vector)

XTI = vector of output generated by transfers to individuals

TG = transfer payments to government (grants to Puerto Rican Government).

XTG= output generated by transfers to government.

TO = Other miscellaneous transfers.

XTO= output generated by other transfers = vector of employment coefficients (persons employed per million dollars of output for both 1992 and 2006)

vector of employment coefficients (persons employed per million dollars of output for both 1992 and 2006)

vector of employment coefficients (persons employed per million dollars of output for both 1992 and 2006)

XN= direct and indirect employment generated by output solutions to the model (in our case the output for the three categories of transfers for both 1992 and 2006)

vector of wages and salaries coefficient (wages divided by output both for years 1992 and 2011)>

vector of wages and salaries coefficient (wages divided by output both for years 1992 and 2011)>

XS = W = income generated by the output solutions to the model for the three categories of transfers for years 1992 and 2006

Results

The results will be presented in the following order: results of the model for transfers to individuals, results for transfer to government and results for other transfers. The years analyzed are 1992 (our base year) and estimates for year 2011 using the I-O table of 2002. First we analyze the impact on output, employment and income generated by transfers to individuals (earned and granted). Second impacts of government and other transfer will be analyzed.Transfer to individuals

The results are obtained by solving the open input- output model. Employment and income are obtained by multiplying the results by the employment and income coefficients vectors. Table 4 shows the allocation of transfer payments to individuals to the final demand vectors of the input- output model. The table is a summary of the 93 by 1 column vector of final demand. The data for year 2011 is used with the latest I-O table for year 2002.

An analysis of table 4 data shows that from 1992 to 2011 earned transfers increased from $1,612.2 million to $5,796.3 million, an annual rate of growth of 6,8 %. Granted transfer (at 1992 prices) increased from $1,527.1 to $3,589.8 million, a rate of growth of 4,60 % per year. In other words, in 1992 granted transfers constituted 48,6 % of total transfers to individuals while during 2011 granted transfer decreased to 38,2 % of total transfers to individuals. For year 2011 net granted transfer at 1992 prices constituted 5,2 % of GDP at 2002 prices ($69,168.8). These figures are very significant and contradict the common view that transfers to individuals are "generous" and constitute one of the pillars of our economic development, making the economy of the island highly dependent on US taxpayers.

Output by Industrial Sector Generated by Transfers

Applying equation (1) we get as solution the output necessary to satisfy the final demand (in our case final demand equals the consumption generated by transfer payments to individual). The results are summarized in table 5. A glance at table 5 shows an increase in output5 generated by granted transfers and earned transfers from 1992 to 2011. Output generated by earned transfers increased significantly, from $2,431.8 to 9,760.7 million. The industries more favorably impacted by earned transfer were manufacturing, trade, and finance, insurance and real estate and transportation, communications and public utilities. Industries more favorably impacted by granted transfers are trade, professional services, finance insurance and real estate, manufacturing, public utilities and medical and health services.

A comparative analysis of table 5 and table 4 shows that for each million dollars increase (or decrease) in transfer to individual output of the system will increase (or decrease) by $683,953 (a output multiplier of 1.683953).

Impact of Transfer to Individuals in Employment

Using the data of output together with employment coefficients we get the direct and indirect employment generated by transfers payments (see equation 4 above). table 6 shows the employment generated by transfers to individuals (earned and granted).

Some of the results derived from table 6 are as follows:

• Direct and indirect employment generated by earned transfer payments to individuals increased at annual rate of 3.53 % from 1992 to 2011, increasing from 49,446 to 95,648 during this period. Employment generated by granted transfers increase only 1.09 %.

• Percentage wise during 2011 employment generated by earned transfers to individuals amounted to 61.7 % of total employment generated by transfer payments to individuals and granted transfer amounted to 38.2 % of total transfers, while in year 1992 the percentage was 50.6 %. and 49.3 % respectively. These figures show a reduction of granted transfer and an increase of earned transfers as percentage of total transfer to individuals during this period.

• Total (direct and indirect) employment generated by transfer payments to individuals amounted to 14.4 % of total employment in Puerto Rico for year 2011.

• During 2011 24 % of employment generated by transfers to individuals was in wholesale and retail industry while in 1992 was 18.8 %. During 2011 employment generated by transfers in medical services amounted to 22.5 % of total employment generated by transfers to individual. Another industry where employment generated by earned transfers was significant was other services (mostly professional service and educational services).

For each 100 million dollars of increase (or decrease) in transfer to individuals the economy gains (losses) 1,270 jobs6.

Impact on Value Added in Wages and Salaries

One important result of the Input-Output model is the direct and indirect income (wages and salaries) generated by transfer payments. As explained before transfer payments are allocated to the exogenous vectors of final demand. The model is solved giving as solution the direct and indirect output by industrial sector. To produce the output workers constitute one of the main inputs of the production process. Workers are paid wages and salaries. Table 7 shows direct and indirect income in form of wages generated by transfer payments to individuals.

• Data on table 7 shows that, during 2011, of the total wage income generated by transfers to individuals earned transfers generated 61.7 %.

• Trade, transportation, communications and public utilities other services and finances were the most favorable impacted by transfer payments to individuals. Of total income generated by transfers to individuals, 10.8 % was generated in manufacturing industries, 24.4.% in trade, public utilities 13.51 and 13.52 % in professional services.

• Once again earned transfers are responsible for most of the direct and indirect impact on the wages and salaries of workers.

• Income generated by earned transfers to individuals increased at annual rate of 6.62 % while granted transfers rate of growth was 3.61 % from 1992 to 2011.

• The results of the model shows that for each million dollars increase (or decrease) in transfer to individuals wages in the economy will increase (or decrease) by $274,663. For instance a reduction of 100 million dollars in transfer to individuals will reduce wages by $27,466,283.

Transfers to government and others

Puerto Rican Government receives grants from the Federal Government. During fiscal year 2006 the government received a total amount of $2,378.2 million. Table 8 shows gross transfers of Federal Government to Commonwealth Government for fiscal year 2011 in current prices.

Figures shown in table 8 were adjusted by payments made by local government to Federal Government and deflated to 2002 prices.

The procedure was necessary to run the Input-Output model whose base year is fiscal year 2002.

As with transfers to individuals, the results are shown for the variables output, employment and income. The transfer to governments was allocated to final demand vector of government expenditures (Municipal and Commonwealth) except for the School Lunch Program that was allocated to the educational service industry. Table 12 shows a summarized version of the results of the input-output model for selected years. The selected fiscal years were chosen according to the availability of input-output tables, except for 2006 when we assumed the structure of 1992.

Table 9 shows results for years 1967 to 2011 at current prices, since we used input-output data bank for each of these years. However, for year 2011 we used constant price figures to run the model since we were assuming 2002 structure. The analysis of data of table 9 shows that:

• Federal Grants to Commonwealth Government, public enterprises and municipalities increases at annual rate of 9,6 % from 1967 to fiscal year 1987, compared to 4,4 % from 1992 to 2011.

• During fiscal year 2011 grants to Puerto Rican government generated 112,016 direct and indirect jobs. Adding the jobs created by other transfers the amount increases to 125,508. Impact on jobs creation of Federal Grants increase from 85,472 in 1992 to 112,016 in fiscal year 2011 (an increase of 26,544).

When jobs created by transfers to individuals are added to above figures total increases to 280,393.

The reader should consider that implicit price deflator of government expenditure increased by 43,3 % from 1992 to 2006. Therefore the annual rate of growth of federal grants to the local government was only 0,56 % during this period.

• The same pattern can be observed in income generated by federal grants to Commonwealth Government and other transfers. A significant growth in the direct and indirect income generated by other transfers (17,5 % at current prices and 9,6 % at constant 1992 prices). On the other hand, we observe a relatively slow growth for the same variable of government grants (8,61 % in current prices and only 3,4 % in constant prices). However the impact on income is much higher than in employment which means that salaries are increasing at a higher rate than jobs at least using the data bank of 1992 input-output with 2006 income and employment coefficients.

SUMMARY OF THE RESULTS

When jobs created by transfers to individuals are added to above figures total increases to 280,393.

The following findings can be derived by the analysis of table 10:

• For year 2011 earned transfers to individuals is the major component of total transfers to the island, accounting to 42,8 % of total transfer payments. This category of transfers also generates 34 % of direct and indirect employment. From 1992 to 2011 earned transfer experienced an annual rate of growth of 6,85 %.

• Granted transfers to individuals account for 26,5 % of total transfer and create 21,1 % of employment. Granted transfers experienced an annual rate of growth of 4,7 % from 1992 to 2011.

• Net grants from federal government to Commonwealth government amounted to 27,3 % of total transfer payments and was responsible for the creation 112,016 jobs or 39,9 % of total direct and indirect employment created by total transfer payments (280,393). Annual rate of growth for this category of transfers was 4,7 % from 1992 to 2011.

Total direct and indirect jobs created by total transfers during fiscal 2011 amounted to 280,393 which constitutes 26,8 % of total employment (1,047,000)

• Other transfers increased from $204.0 million to $445.8 million from 1992 to 2011 (this kind of transfer payments are mainly from nonresidents), an annual rate of growth of 3,8 % for the same period.

• Total net transfers from Federal Government, and other sources, to Puerto Rico amounted to $13,530.2 million during fiscal year 2011. From 1992 to 2011 total transfer experienced a 5,5 % rate of growth. Total (direct and indirect jobs created by total transfer amounted to 280,393 which constitute 26,0 % of total employment of the island for that year.

• Using the model we can also estimate the contribution of transfer payments to gross domestic product and other macroeconomic variables. Gross domestic product (GDP) of the island was $98,757.0 million for fiscal year 2011 ($69,168.8 million at 2002 prices). GDP for fiscal year 2002 was approximately 50,5 % of gross output (intermediate plus final demand). For year 2011 gross output generated by transfer payments amounted to $21,490.6 (at 2002 prices), therefore the contribution for transfer payments to GDP of the island was approximately 15,4 %.

For each $100 million of increase (or decrease) in total transfer, direct and indirect employment will increase (or decrease) by 2,072, output generated in the economy will increase (or decrease) by $158.8 million, and wages will increase (or decrease) by $38.6 million (estimates based on 2002 input-output model together with updated employment and income coefficients for year 2011).

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

A relatively recent article by Gary Burtless and Orlando Sotomayor argue that "because Puerto Rico is the recipient of substantial net transfers from the mainland government, taxpayers on the island do not have to pay for all the government benefits received by the island residents. Low income Puerto Ricans enjoy relatively generous (emphasis of mine) income supplements and retirement benefits without imposing heavy tax burdens on highly compensated workers".

In the analysis they failed to make a clear distinction between granted and earned transfers. The Puerto Rico Planning Board classifies individual transfer payments into two categories: "earned transfers" and "granted" transfers (Table 2). The first category is defined as those transfers received by persons and government for previously rendered services or for previous payments to the federal government, like for instance, veterans and social security payments, respectively. The second category of transfers are those given unilaterally to Puerto Ricans. They cannot be related, at least directly, to previously rendered services or payments. When analyzing both types of transfers the federal government program of transfers to Puerto Rico does not seem so "generous". The starting point when analyzing transfer payments is to separate both types of transfers.

It is important also to emphasize that any analysis of transfer payments to the island should start by using net amounts; otherwise the analysis will be biased. Since we are dealing with two economies, the flows from both should be taken into account.

The purpose of this work was to estimate the direct and indirect economic effects of federal and other transfer payments to Puerto Rico. The economic impacts was estimated for three economic indicators namely, gross output, direct and indirect employment and direct and indirect wage income. An input output model, together with employment and income coefficients, were used to obtain the results.

An analysis of the data shows that from 1992 to 2011 earned transfers increased from $1,645.1 million to $5,793.3 million, an annual rate of growth of 6,85 % while granted transfer to individual increased from $1,493.8 to $3,589.8 million an annual rate of growth of 4,7 % per year. In term of percentage share, in 1992 granted transfers constituted 30,6 % of total transfers while during 2011 granted transfers decreased to 26,5 % of total transfers while earned transfer increased from 33,7 % of total transfer to 42,8 % during the same period. There is a clear tendency for granted transfer to decrease and earned transfer to increase.

Transfer payments generate interindustry output, employment and income. A glance at data on output shows a greater impact of earned transfer than granted transfers from 1992 to 2011. The industries more favorably impacted by earned transfer were trade, finance, insurance and real estate and manufacturing. But most of the impact was on the service sector. Industries more favorably impacted by granted transfers were trade, professional services, finance insurance and real estate, manufacturing, public utilities and medical and health services.

During 2011 employment generated by earned transfers to individuals amounted to 34 % of total employment generated by transfer payments. The corresponding figure for granted transfers was 21,1 % of total transfers. Total (direct and indirect) employment generated by transfer payments to individuals amounted to 14,4 % of total employment in Puerto Rico for year 2011.

During 2011, earned transfers generated 73,5 % of the total income generated by transfers to individuals. Manufacturing, trade, and professional services were the industries the most favorable impacted by transfer payments to individuals. Of total income generated by transfers to individuals, 19 % was generated in manufacturing industries, 17,4 % in trade and 16 % in professional services. Once again earned transfers were responsible for most of the direct and indirect impact on the wages and salaries of workers.

Puerto Rican Government receives grants from the Federal Government. During fiscal year 2011 the government (Commonwealth, Municipal and Public enterprises) received a total net amount of $3,701.3 million (at constant 2002 prices). Federal Grants to Commonwealth Government increases at annual rate of 4.74% from 1992 to fiscal year 2011, while other transfers increased at of 4,2 %. During fiscal year 2011 grants to Puerto Rican government generated 112,016 direct and indirect jobs. Adding the jobs created by other transfers the amount increased to 125,508. The impact of government grants on jobs creation increase at a rate of only 1.4% from 1992 to 2011 compared to 3,7 % annual rate from 1967 to 1992 (this in spite of the increase in current price federal grants to the Commonwealth Government).

Total net transfers from Federal Government, and other sources, to Puerto Rico amounted to $13,530.2 million during fiscal year 2011 (at constant 2002 prices). From 1992 to 2011 total transfer experienced a 5,5 % rate of growth. During fiscal year 2011 total (direct and indirect jobs created by total transfers amounted to 280,393 which constitute 26,0 % of total employment of the island for that year.

Using the model we can also estimate the contribution of transfer payments to gross domestic product and other macroeconomic variables. Gross domestic product (GDP) of the island was $98,757.0 million for fiscal year 2011 ($69,168.8 million at 1992 prices). GDP for fiscal year 2011 was approximately 50,5 % of gross output (intermediate plus final demand). For year 2011 gross output generated by transfer payments amounted to $21,490.6 (at 1992 prices), therefore the contribution for transfer payments to GDP of the island was approximately 15,4 %.

The results presented in this work shows that the argument that Puerto Ricans enjoy relatively generous (emphasis of mine) income supplements and retirement benefits without imposing heavy tax burdens on highly compensated workers failed to distinguish that most of the transfer payments to individuals were in the category of earned transfers. It is doubtful that this type of transfer "impose heavy tax burdens" to American tax payers.

Since we are an open economy most of the income generated by transfer to individuals is spent of good and services a substantial amount of which comes from United States. (Angel L. Ruiz and Fernando Zalacaín 1994).

It is also doubtful that earned transfer to individuals (especially transfers in the form of pensions and payments to veterans) have any significant impact on the labor rate of participation or the incentive to work. Low labor rate of participation is determined by other factors other than the small amount of granted transfer payments (among which are scholarships).

NOTAS

1 This article is an updated version of an article published in RU International Journal, vol. 3(1) 2009 in Bangkok, Thailand. The current version includes recent data used with a new input-output model based on the latest input output matrix published by the Puerto Rico Planning Board. Volver

2 Personal Consumption, investment, government consumption, and exports vectors. Volver

3 The matrices are available to the reader on request to the author. Volver

4 See Richard stone, John Bates y Michael Bacharach, A Programme for Growth (No.3): Input Relationship 1954-1966, Cambridge Department of Applied Economics, England (Publicado en Inglaterra por Chapman and Hall, Ldt., y en Estados Unidos, por M.I.T. Press) Volver

5 Interindustry output is equal to intermediate plus final output while Gross domestic product is equal to gross output minus intermediate output. Gross national product is equal to Gross Domestic product minus rest of the World (income of external firms established in the island, for intance profits). Volver

6 Estimates based in the results of Input-Output models of 2002. Volver

Referencias

1. Burtless, G. y Sotomayor, O. (2006). Labor supply and Public Transfers. In S. M. Collins, B. P. Bosworth y M.Soto Class (eds), The Economy of Puerto Rico, Restoring Growth (pp. 82-142). Washington: Brooking Institution, Center for the New Economy. [ Links ]

2. Collins, S. Bosworth, B. y Soto-Class M. (2006). The Economy of Puerto Rico: Restoring Growth. Washington: Brookings Institution Press. [ Links ]

3. Junta de Planificación de Puerto Rico. (2002). Informe Económico al Gobernador 2002, capítulo V. Insumo-Producto de Puerto Rico. [ Links ]

4. Junta de Planificación de Puerto Rico. (2001-2002). Multiplicadores Interindustriales 2001- 2002. [ Links ]

5. Junta de Planificación de Puerto Rico. (2001-2002). Insumo-Producto, 2001-2002. Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, Oficina del Gobernador. [ Links ]

6. MacEwan, A. y Ruiz, A. (2007). Washington Dollars and the Puerto Rican Economy: Amounts, Impacts, Alternatives (monografía 135). Unidad de Investigaciones Económicas Departamento de Economía (UPR). [ Links ]

7. Puerto Rico Planning Board, Input-Output Tables, 1992 and 2002. Recuperado de http://www.jp.gobierno.pr/ [ Links ]

8. Puerto Rico Department Of Labor, Series of Employment by Industry. Recuperado de http://www.trabajo.pr.gov/estadisticas.asp [ Links ]

9. Ruiz, A. L. (1994). The Impact of Puerto Rico's Economy in the United States. New York: Hunter College, City University of New York (CUNY). [ Links ]

10. Ruiz, A. L. (2009). United States Transfers to Puerto Rico. RU. International Journal, 3(1), 1-24. [ Links ]

11. Ruiz, A. L. y Choudhury, P. (1978). The Impact of Food Stamp Program on the Puerto Rican Economy: An Input-Output Approach. Puerto Rico: Universidad de Puerto Rico. [ Links ]

12. Ruiz, A. L. y Meléndez, E. (eds.). (1998). Economic Effects of Puerto Rico Status Alternatives. San Germán: Interamerican University Press. [ Links ]

13. Ruiz, A. L. y Zalacain, F. (1980). Impacto del Déficit en la Balanza Comercial y los pagos de transferencia federales sobre el Crecimiento en el Sector de los Servicios. Puerto Rico: Universidad de Puerto Rico. [ Links ]

14. Ruiz, A. L. y Zalacain, F. (1994, april). The Impact of Transfer Payments (Federal and Others) to Individuals and to Government on the Puerto Rican Economy. Ceteris Paribus, 4(1), 19-24. Recuperado de http://www.iis.ru.ac.th/download/journal_iis_Vol3(1).html [ Links ]

15. Ruiz, A. L. y Zalacain, F. (1994, october). The Economic Relation of The United States and Puerto Rican Economies: An Interregional Input-Output Approach. Ceteris Paribus, 4(2), 1-7. Recuperado de http://www.iis.ru.ac.th/download/journal_iis_Vol4(2).html [ Links ]