Introduction

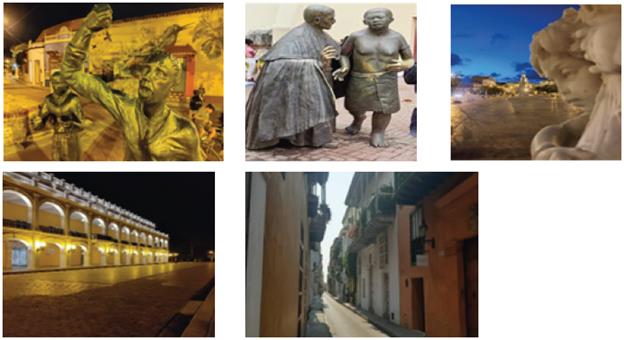

The study addressed the problem of lack of participation which arose due to current practices and contents that were text-book oriented and not very significant to the participants. The problem increased with the abrupt transition to remote learning due to the Covid-19 Pandemic. To make learning meaningful and engaging youngsters worked with authentic printed and audio-visual texts in English for discussing the historical-tourist sites of their city, Cartagena de Indias.

For those local teachers who follow pedagogical practices imported from English-speaking countries in a relatively unquestioning manner, lessons may have limited use to their students, who are asked t adapt themselves to procedures and practices which neither they nor their teachers feel any sense of ownership. By contrast, where teachers appropriate and reconfigure imported pedagogical practices, combining the global with the local, the results are far more optimal (Canagarajah, 1999).

The transition to remote learning forced the use of video conferences, communication in social networks, and email with the challenge of maintaining quality instruction. Paraphrasing Spearce (2021), in a tech-dominant decade, one ingredient remained consistent: excellent teaching and a positive classroom setting. The purpose of this study was to test how the introduction of local culture and history topics could connect with the learners' hearts and minds and develop awareness that they are citizens of the world. Task-Based Learning and computer literacy contributed to achieving the pedagogical goal.

The pedagogical innovation met the objective of making the best circumstances to form independent and engaged learners in an online environment. Twenty-two youngsters gave a historical account of six historical landmarks of Cartagena de Indias in a synchronous session on a video platform. Remote learning made use of authentic multimodal materials, friendly apps, video editors, and voice simulators, among others, that allowed the preparation and delivery of content.

A positive classroom setting, situated teaching, and task-scaffolding contributed to achieving the real-life goal of giving a guided city tour (Appendix C). The participants engaged with their area of interest within a Task-Based-Instruction (TBI) framework (Ellis, 2020) in which they took greater control and enjoyed a real-life learning experience.

The article presents the method, the population, and the pedagogical intervention. It discusses workshop number two (with details in Appendix C) and the findings (supported with data in Appendix A, B, and D), and suggests further research.

Method

The study took place at a school affiliated with a branch of the armed forces. The participants belonged to one of the teacher-researchers classes, making it a convenient sample for the study. It examined the promotion of speaking to discuss issues about Cartagena de Indias as a world heritage site.

This qualitative-exploratory study followed action research which according to Kemmis, & McTaggart (1988, p. 5):

is a form of collective self-reflective inquiry undertaken by participants in social situations to improve the rationality and justice of their own social or educational practices, as well as their understanding of those practices and the situations in which the practices are carried out.

The diagnosis stage was on-site, but due to the Covid-19 pandemic, the action and evaluation stages remained online.

In the pedagogical intervention of the action stage, the 10th graders concentrated on the understanding of authentic texts (Kim, 2002) and performance of real-life tasks such as TV-like reports, oral presentations, interviews, verbal narrative descriptions, and elaboration of videos. These activities combined individual, pair, and whole-class work.

On the other hand, big ideas enhanced the understanding of the landscape of the city. Critical pedagogy with Escarbajal-Frutos (2010) and Crookes (2012) encouraged the analysis and evaluation of the claims about the history, economy, and traditions of Cartagena (Appendix C). A global event like colonization was problematized and so were its ideologies. The locations of the city were scrutinized with fresh eyes. There was an understanding that the contacts between the global and the local were not casual, and that Cartagena is a world heritage city for it represents the permeating of the 'particular' and the 'universal' as stated by Robertson (1995)).

At the end of each workshop, participants spoke with their voices about the facts and events discussed. The paper includes excerpts from Workshop No. 2 to exemplify the content, methodology, contextualized materials, and assessment.

The inquiry with a class of 22 English language learners was approved by the faculty of Universidad de Caldas, the school and parents gave their consent for the students to participate (See Appendix E).

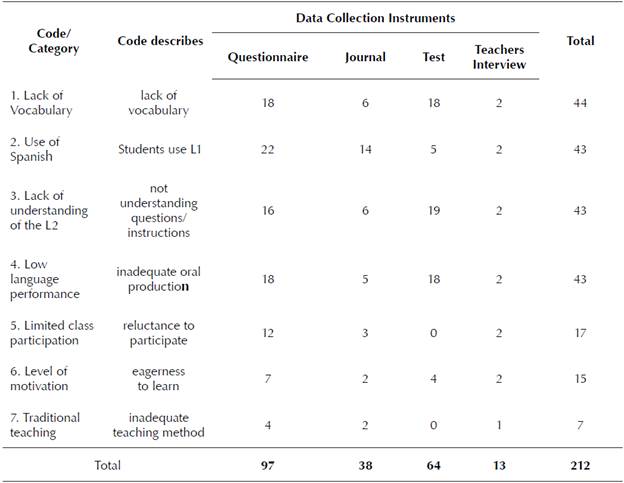

A summary of the data triangulation applied in the diagnostic stage appears in Appendix A, Table 3. Classroom observations and a journal contributed to identifying the research problem, which was a dissatisfaction with their competence to speak due to lack of vocabulary, not understanding questions/ instructions, and inadequate teaching methods which resulted in a reluctance to participate. The interviews recorded and validated the participants' perceptions about topics, and teaching methods. The students took a four-skill diagnostic test and a survey in which the weakest skill was speaking. The transcriptions of the teacher's journal corroborated that speaking was deemed weak. The teacher-researchers gathered data on TBI, glocal knowledge, and computer literacy to establish their role in L2 development. An external observer and participants gave insights into lesson planning and assessment.

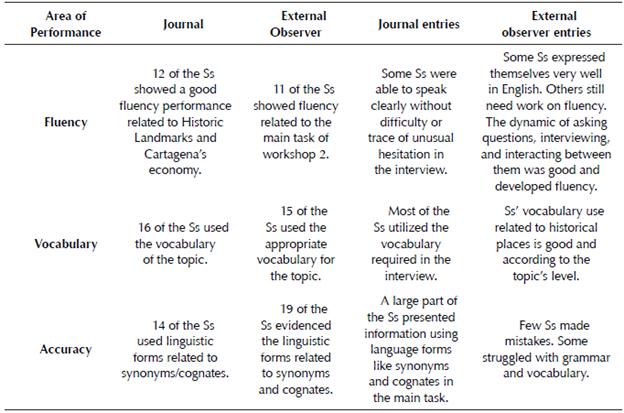

The preliminary data analysis applied codes instrument by instrument and then the data were triangulated. The frequency of response helped establish the categories for the diagnostic stage which were lack of vocabulary and understanding, use of L1, language performance, and low participation. The data analysis after the pedagogical intervention identified (via triangulation) the constructs, fluency, vocabulary, accuracy, and local knowledge. These characterized the participants' enhanced performance. In the remote environment, the participants showed underuse of grammar-spelling checkers and resources to process texts, voice, and videos, or to find relevant academic information.

Pedagogical Innovation

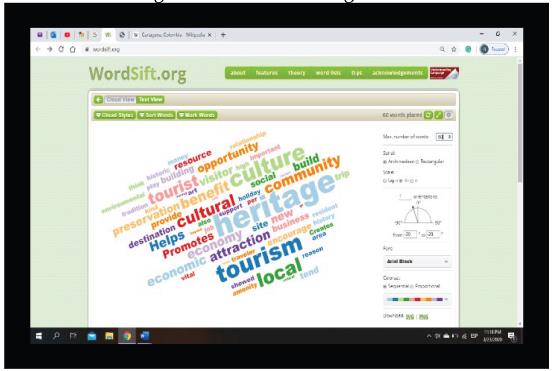

The pedagogical innovation posed the challenge of organizing goals, objectives, content, and outcomes in a way that would be meaningful to tenth graders who had evaluated current practices poorly. Added to that, the unforeseen change to a remote-learning environment forced the inclusion of computer literacy skills for learners to exploit resources. For example, the use of the right clicks of the mouse for synonyms; the applications Wordsift. Org to identify keywords, Text-to-Speech to hear a printed passage; and Audio-Converter to prepare assignments by simulating voices for their oral presentations.

The teacher-researchers, two fellow English language teachers, and the project supervisor provided feedback for the study and the workshops: They made sure that the project was in line with the Ministry of Education's (2005, 2016) principles and content that call for the formation of students to be competent by understanding issues from several disciplines.

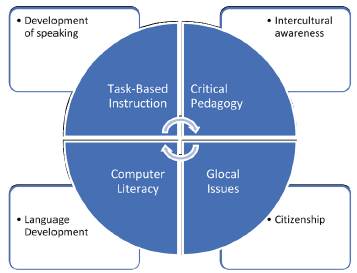

The authors felt that Task-Based Instruction facilitated engagement in L2 acquisition while preparing, performing, and evaluating real-life tasks. The classroom dynamics promoted cooperation to achieve the common goals of preparing themselves to guide a tour in Cartagena, a world heritage city, by connecting participants with their background, history, and everyday world. Engagement increased with the discussion of glocal topics and oral proficiency development provided a sense of success. Figure 1 synthesizes the relationship between content, teaching principles, and goals.

As it will be exemplified below in Workshop 2, the content, linguistic and communicative purposes brought elements of critical pedagogy to discuss glocal issues for reinforcing the L2, especially on speaking. Similarly, the syllabus included topics of intercultural awareness citizenship and economy. It had a scope and sequence that balanced the degree of difficulty of the authentic materials, tasks, and assessment. Each took over eight hours of instruction and assessment.

The Pre-Columbian History of Cartagena de Indias- The Zenu Gold Museum.

Historic Landmarks and the Economy of Cartagena.

The Palace of the Inquisition.

San Pedro Claver Complex.

Landmarks of the Independence of Cartagena.

Cartagena de Indias, World heritage city.

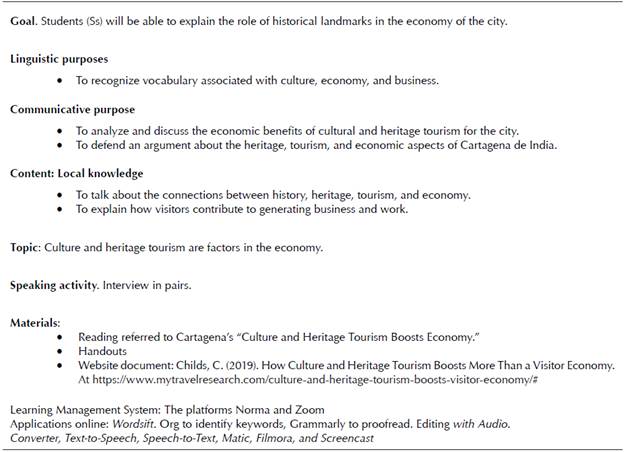

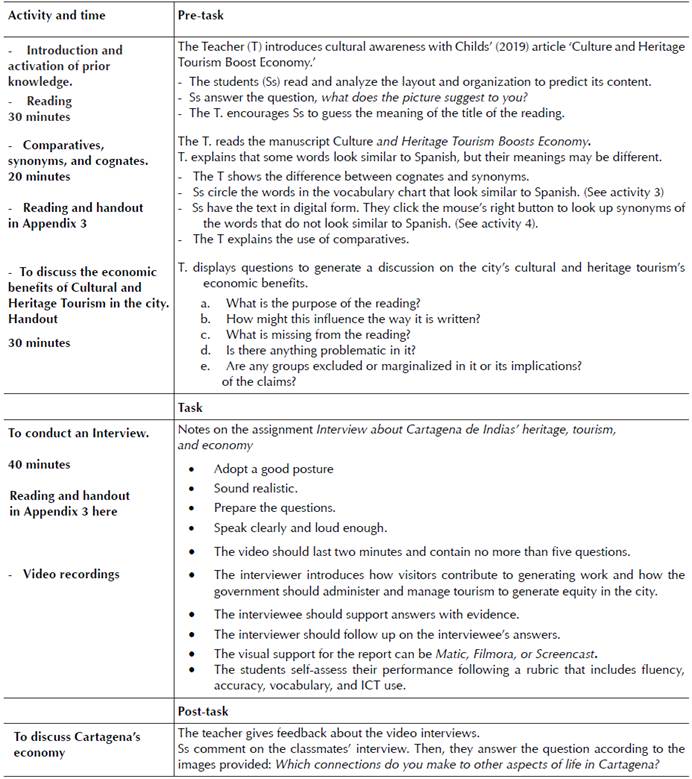

To make the instructional design visible to the readership of this journal, this article presents in Table 1 the lesson plan for Workshop No 2, and the handout appears in Appendix C. Each workshop section included: goal, linguistic purpose, communicative purpose, pre-tasks, task, post-task, and assessment. Note: T stands for teacher and Ss for students.

Task-Based Instruction facilitated lesson design with pre-tasks, tasks, and post-tasks as illustrated in Table 2. Individual, pair, and group work provided opportunities for interaction. Topics connected to new learnings while scaffolded activities reinforced their L2 experience, reinforced vocabulary, and kept participants motivated. As discussed later, participants gained in computer literacy, vocabulary retention, and oral expression.

Ensuing workshops received adjustments in form, content, layout, type of activities, and ways of assessment. The handout in Appendix C illustrates the implementation of TBI, activities, and assessments. It appears here to encourage other teachers to replicate this study since there is a genuine interest from pre-service, and in-service teachers to explore the potential of global and local issues in school curricula.

Findings

This study established the introduction of local knowledge topics and computer literacy-enhanced Task-Based Instruction to address learner disengagement and lack of confidence. These factors contributed highly to L2 development. The pedagogical innovation contributed to L2 development because participants studied and reflected on the history, the meeting of cultures, and the economy of their immediate context. Inclusive and sustainable tourism, which are topics widely discussed in local newspapers, were the subject of class debates. The data also suggest that a) TBI promoted cooperation towards a common goal, b) participation increased, c) vocabulary retention improved due to the activation of the participants' previous knowledge, and d) real-life tasks contributed to fluency development.

Finding No. 1. Discussing Global and Local Issues Awoke the Participants' Interest in Speaking with their Voices

The participants communicated better when they understood and shared the knowledge acquired in and out of school. The pedagogical innovation activated their background knowledge of history, economy, and tourism. They conceptualized their city and understood why it has so many visitors and is a world heritage site. Class debates and discussions on global and local issues showed the potential for learners to understand their immediate world and hopefully transform it. The integration of local knowledge contributed to speaking development because learners had a working knowledge of Cartagena's history and landscape. After the first workshop, most participants affirmed that they gained fluency, accuracy, and vocabulary; for example, Student No. 7 held "Aprendí un vocabulario amplio respecto al tema y a comprender textos tras identificar los verbos principales y el contexto". Student No. 12 affirmed: "Aprendía vocalizar mejor algunas palabras y sus significados.

Familiar topics contributed to fluency, and speaking progress was evident since the class showed enthusiasm and confidence in speaking (See also Table 5 in Appendix D). This finding agrees with Crookes' (2012) statement that a local topic as a deliberate choice brings to the curricula issues of identity. For instance, a participant affirmed: "I learned many things. Acquiring more knowledge about the city was terrific. (Workshop 1) We live in it, but we do not know its history and others. Apart from it, it helped a lot in expressing myself in English. Fluency" (Student 7, Self-assessment).

The data showed the progress of with the integration of local knowledge. In the sessions, there was room for casual conversations and discussions to interpret printed and spoken information about local and global issues. For example, the participants mentioned that the history behind the inquisition made an impact on them. After the workshop on the Palace of the Inquisition, the participant No. 17 said: Aprendí palabras nuevas, mejoré mucho la fluidez, y aprendí de la historia del lugar. The introduction of local and global problems can be replicated in those urban schools where the standard topics and activities tend to alienate learners. L2 studies can contribute to an interdisciplinary curriculum and engage learners in debating global citizenship.

Finding No. 2. TBI Engaged Beginner ELL

The second finding responds to the question: How can TBI engage participants in speaking about global and local issues? TBI engaged the beginner English L2 learners because input came from teacher talks, students' presentations, and authentic information derived from multimodal sources. Throughout the cycle, the participants had opportunities to achieve goals by using spoken language to express what they understood, felt, and thought about the issues discussed. They worked in pairs and small groups and volunteers made a presentation.

Task-Based Instruction (TBI) had a positive impact on speaking. The finding coincides with Torky (2006), who acknowledges the potential of TBI to promote speaking. A teacher's journal, recordings of the online classes, and the external observer's point of view indicated that TBI allowed learners to develop speaking competence, whereas average scores corroborated the progress made.

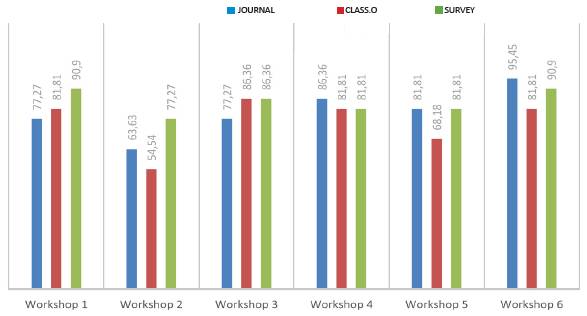

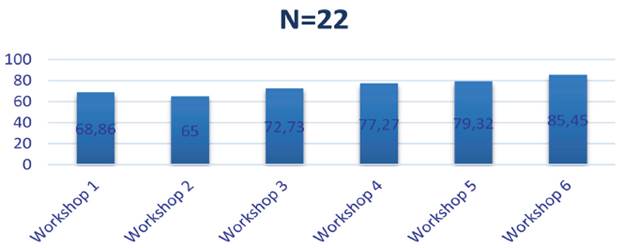

The students' overall scores, shown in Figure 2, showed significant progress. Average scores were satisfactory for Workshops 1 and 2; very satisfactory for 3 and 4, and highly satisfactory for 5 and 6. The degree of difficulty in the second one exemplified in this article, explains why there was a lower performance than in the first one. For the other workshops, progress was steady. Figure 2 presents the scores, on a scale from 0.0 for participants obtained in each workshop.

By the same token, the external observer in Workshop 2 affirmed: Some Ss expressed themselves very well in English. Some others still need to improve their fluency. The dynamic of asking questions, interviewing, and interacting between them was good and improved their fluency. Furthermore, in the survey of the student's self-assessment in Workshop 6, Student 15 expressed: "I learned the right words to describe a place, stating how much

I liked it." Oral fluency gains are attributable to the pedagogical intervention.

This study showed that combining texts in English as the primary communication vehicle mediated with authentic multimodal resources, discussion of glocal issues, and computer literacy positively impacted speaking; see Table 5 in Appendix D. Thanks to the pedagogical intervention, participants managed to express themselves in English, clearly without difficulty or hesitation. For example, in Workshop 4 the Teacher's journal states, "Some learners did a great job in their performance. The number of Ss with a fluent presentation was the same as in previous sessions." The data triangulation suggests that the students' oral performance increased notably since learners evaluated their performance well because the pedagogical intervention structure brought them cognitive, social, and affective benefits. For instance, in Workshop 5, Student 8 self-assessed, stating: "I gained fluency in English" [Mi fluidez en el idioma aumentó un poco más].

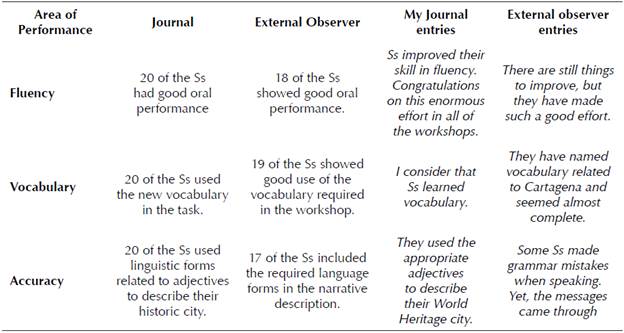

On the other hand, the data triangulation for the last workshop, the teacher-researcher's journal, and the external observer registered progress in fluency, vocabulary, and accuracy (Appendix B). Besides, the external observer and the journal data pointed out that participants displayed a positive attitude and disposition towards learning. They faced a challenge that helped them drive their proficiency development forward thanks to the application of TBI's principles such as scaffolding, recycling, active learning, integration, from reproduction to creation, and reflection. In addition, printed and multimedia material provided input on culture, language, and citizenship, while work on the L2 prepared participants for oral interaction.

Finding No. 3. ICT contributed to developing confidence

The contribution of information and communication technologies (ICT) to learning was fundamental since due to the Covid-19 pandemic, it was necessary to move to an online environment with the Zoom platform in the synchronous session, and elaborating video consulting websites, email, social networks, and phone messaging allowed communication, advising, and submission of assignments.

In the diagnostic stage, the two teachers interviewed coincided that students were afraid to speak. The sessions promoted a safe speaking environment with practices such as the use of ICT resources and teamwork that would inspire confidence. The integration of ICT contributed to speaking development since it allowed the interaction spaces in the online world and helped develop fluency through the Text-to-Speech application, the promotion of grammar-spelling checkers, the production of videos, access to websites, and applications, to name a few. McDougald (2013) anticipated the need to use new technologies because of accessibility to authentic material, which fosters pedagogical and real-world tasks. For instance, the external observer stated: "Students seem to manage tools that help to present their activities. Some of them use apps that make the interview look more real; some others use other tools, but all of them use different designs to present their interviews." (Workshop 2). In the survey of the students' self-assessment in Workshop 2, No. 17 claimed to have gained confidence in expressing. After workshop 5, Student No. 15 affirmed to have picked up the pronunciation of many words. [Aprendí la pronunciation correcta de muchas palabras].

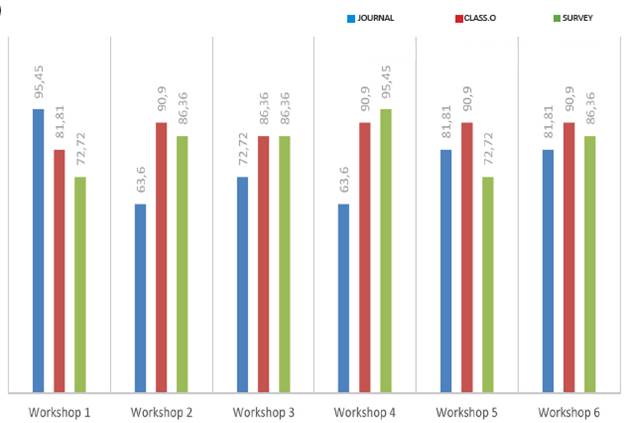

Most participants claimed gains in confidence to speak since ICT applications helped them prepare. For example, Text-to-Speech for hearing the printed text, Wordsift, to identify overused expressions, and Audio-Converter to simulate voices containing rehearsed expressions, representing knowledge of the topic, its lexicon, and structures. In addition, communication was central; the participants understood their immediate environment better and took a position on issues close to their hearts and minds. At the same time, Wordsift highlighted the keywords of the passage. In figure 4, readers can observe the contribution of ICT to L2 acquisition. It displays the triangulation of data drawn from the teacher-researcher journal, class observations, and students' self-assessments.

Evidence points out that ICT had a positive impact on oral production. The decision to introduce computer literacy in every lesson proved helpful. ICT resources facilitated class interaction and communication in an online environment abruptly adopted by the school due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

This finding coincides with Chong and Reinders (2020) who conducted a meta-analysis of 16 qualitative research reports on the connection between TBI and ICT. This combination contributes to

Facilitating collaborations, interactions, and communications.

Cultivating positive attitudes towards language learning.

Facilitating student-centered learning.

Developing language skills.

Developing non-language skills.

Chong and Reinders (2020) were correct in their appreciation. The circumstances of the Covid-19 pandemic forced advances in computer literacy which facilitated L2 processing. At the beginning, issues of connectivity increased the workload of learners and teachers; fortunately, ICT resources engaged learners when they realized they could learn and perform with, from, and through them (Castillo, 2021).

Discussion

A diagnostic stage identified a pedagogical model focused on grammatical structures and vocabulary that hardly connected to the learners' needs and interests. In the action stage, the teacher's experience and the data collected contributed to designing a pedagogical innovation, staying away from topics and activities that merely illustrate grammar or lexicon. In comparison, the evaluation stage demonstrated that discussions on glocal topics engaged participants. Appendix B displays the techniques and instruments employed in the action and evaluation stage.

The authors realized that allotting time and support to activities, offering varied sources of input, adapting it, and elaborating on the learners' production proved helpful. Furthermore, the first and the target languages were on equal footing, especially for discussions beyond the participants' current English language proficiency level. A balance of focus on form and meaning in the syllabus and the feedback contributed to developing self-confidence in oral production.

A critical pedagogy stand (Escarbajal-Frutos, 2010) became the teacher-researcher's option to promote glocal knowledge and cultural awareness. The participants communicated about their immediate environment taking a stand on issues close to their hearts and minds. Thus, this experience can be replicated in those urban schools where standard topics and activities may alienate learners. The study of another language contributes to an interdisciplinary curriculum and engages learners in socio-cultural issues and literacy skills.

Chong and Reinders (2020) affirm that these TBI characteristics: authenticity, usefulness, difficulty, and sequence, when supported with ICT, facilitate opting for authentic texts and activities sequenced in order of difficulty. Since ICT facilitates purposeful or incidental contact with languages and world communities, this project aspires to transforming current practices. The implementation has continued in a Blended Learning, and on-site modalities. A guided tour, in English, at San Felipe Castle fulfilled the participants' desire to continue with the dynamics of the course. Those facts demonstrated the trustworthiness and sustainability of the project.

This study concurs with Torusda and Tunç (2020) that English language teachers' perceptions and beliefs about TBI need further research. On the other hand, it allows asserting that continued teacher education should fill the gap between theoretical knowledge about TBI and implementations relevant to the contexts and settings.

This article reports on an action research study that explored factors that contribute to second language (L2) development in an atmosphere of an abrupt change from on-site to remote learning. The teacher-researcher met the challenge by introducing topics closer to the participants' hearts and minds, and by adding elements of computer literacy. These factors created a low-pressure learning environment that enhanced oral fluency. Further research on interdisciplinary syllabi that connect local and global issues would enhance knowledge appropriation.

Conclusion

This project brought to the forefront the search for meaningful learning. The integration of subjects, content, and skills strengthened the curricula and practices and the study responded to the main question: How can the discussion of global and local issues engage participants?

The beginner English language learners recreated authentic places and events familiar to them and showed confidence in speaking about them. Students assumed an interactive role with classmates and the instructor. They reconstructed the content of teaching in interviews, oral presentations, T.V. reports, and verbal narrative descriptions. The data indicate that the pedagogical intervention proved effective since there was a logical sequence of topics in which situated knowledge and meaning were essential. Those factors paved the way for meaningful learning and increased interaction.

This study demonstrated that the pedagogical intervention worked with beginner-level learners by taki ng as a point of departure familiar themes. These helped learners build self-confidence by moving from simple to complex activities in communicative interactions. Texts and activities went into a crescendo of complexity. The participants did not necessarily have to be taught language forms before tackling topics. The activation of background knowledge, the interaction among peers, and the teacher's support led to understanding and acquisition. The sample workshops and lesson plans included in this article attest to the role that modeling and rubrics play.

The task goal of offering a tour guide to Cartagena historical landmarks was the means for achieving the outcomes. The structuring of the workshops in pre-tasks, tasks, and post-tasks advanced the language to attain the goals. It helped identify a common goal for the online class, structure teams, sequence activities and content, and assess learning.

The findings suggest that including local topics and connecting them to universal ones engaged learners and made interactions meaningful. TBI proved compatible with today's knowledge about second language research (Ellis et al., 2020). The design of a syllabus with TBI involved the careful selection of topics, multimodal channels to make input comprehensible, selection and grading of language, instructions for successful task completion, and tangible outcomes that satisfied participants. In this case, the innovation developed the confidence to speak. Task scaffolding, without rushing learners to speak, allowed them to lose their fears.

ICT also played an important role in language development. At first, it was a matter of trouble-shooting with connectivity and learning management systems. Then it was about using the desktop and Internet resources to the best advantage. Later instruction centered on exploiting the resources to give rein to creativity expressed in creating and sharing content, which is trendy in education today (Harvin, 2022).

This qualitative research captured new beliefs about the relevance of situated topics that are as central as the method chosen to teach them. In the new syllabi, projects with contents of local knowledge aim at developing fluency and enhancing vocabulary. The regular instruction and use of ICT tools make part of today's practices.

Like other pieces of qualitative research, there were limitations such as the small sample size, and potential bias in interpreting the data -although there were views from a participant, a non-participant observer, and a project supervisor. The initial inquiry had to do more with the method -TBI- than with the content -local knowledge. The data had to be analyzed and re-interpreted under that lens. Since the classes were online, the observation differed from those on-site. There were fewer interruptions, and apparently, participants were on-task all the time. A replication of the study in a regular classroom would probably yield similar results.

Further research on the potential of an interdisciplinary syllabus that connects local and global issues would enhance knowledge appropriation. Inquiries would demand teamwork and an open mind towards an interculturality that studies and problematizes current and historical interactions. The knowledge and understanding of cultures would result from using authentic texts and language. Instructors and researchers should try to find answers to these questions: How can a language program propose learning that is meaningful to its community? And how can institutions implement second language programs that are coherent with 21st-century pedagogies?

Note: The authors of this article declare that they have no conflicts of interest and that due credit was given to the authors consulted.