Introduction

Research on police impersonation crime is scarce. Despite numerous reports of impersonation crimes in the media, it continues to be a neglected area in criminology and criminal justice. While only a few empirical articles focusing on police impersonation have been published (e.g., Rennison & Dodge, 2012; Walckner, 2006), international media reports suggest that these crimes may be somewhat common and take many forms, including posing as state personnel, federal officials, members of the military, and law enforcement officers.

According to Gellately (2000), Roman Law first recognised impersonation crimes as lèse-majesté or treason. Currently, impersonators commit a wide variety of unethical and illegal acts. Most impersonation definitions include the following elements:

A person commits criminal impersonation if he knowingly assumes a false or fictitious identity or capacity, and in such identity or capacity he: does an act which if done by the person falsely impersonated, might subject such person to an action or special proceeding, civil or criminal, or to liability, charge, forfeiture, or penalty; or does any other act with intent to unlawfully gain a benefit for himself or another or to injure or defraud another. (US Legal, n.d.)

For this research, confrontational impersonation crime (CIC) is defined as an offense that takes place when an individual obtains the tools or means to mimic the behaviour or character of a powerful person in a face-to-face manner. The impersonator, for example, may take the position of law enforcement agent to commit fraud (often crimes such as theft, robbery, murder, kidnapping) or abuse the power given to the title of the person being impersonated. The confrontational impersonator is unique compared to cyber-impersonators (i.e., nonconfrontational) who steal identities online and rarely come into direct physical contact with their victims.

Many types of impersonation crime are studied in the context of cybercrime, including, for example, identity theft, fake robocalls, and hackers. In these circumstances, an imposter engages in computer cybercrime by acquiring enough personal data and information about another individual to steal cash, credit, or anything of value (Anderson et al., 2008; Del Collo, 2016; Payne, 2017). In other circumstances, impersonation crime may involve social media (e.g., Instagram, email, websites) where an individual will act as the representative of a legitimate account, typically an organisation or a person of importance, with the intent to defraud other users (Zarei et al., 2019; 2020). Distinguishing between cybercrime and confrontational impersonation crime is essential. In the current research, occupational theft is studied rather than identity theft. Confrontational impersonators are not stealing the identity of a specific person; they are stealing the identity of an occupation. Furthermore, this form of impersonation is done through personal confrontational means: face-to-face.

Confrontational impersonation crimes often fall under the dark figure of crime framework, which makes it difficult to determine the frequency of incidents. Several aspects contributing to this problem include victims failing to report, law enforcement agencies neglecting to track incidents, impersonators avoiding capture, and jurisdictions lacking specific criminal codes. These crimes, however, are receiving more recognition as the number of victims increases (Rennison & Dodge, 2012).

Anecdotal evidence of major criminal cases exemplifies this crime’s growing nature and seriousness. Caryl Chessman, also known as the “Red Light Bandit,” for example, approached his robbery, kidnapping, and sexual assault victims in their cars by flashing a red light similar to those used in police cars (Reynolds, 2014). The famous serial killer Ted Bundy impersonated authority figures, including police officers and firefighters, to gain the trust of his victims (Crime Museum, 2017; Rakestraw & Cameron, 2019). In 2011, a mass shooter posing as a police officer shot and killed 69 people in Utoya, Norway (BBC News Europe, 2011). Canada witnessed its worst mass shooting in April 2020, when Gabriel Wortman, a Royal Canadian Mounted Police officer (RCMP) impersonator, set fires in different locations and randomly shot individuals in Nova Scotia. His spree of violence killed 22 people, including a police officer, over 12 hours. Wortman wore a RCMP uniform and drove a police car diverting suspicion and allowing him access to the crime scene (Levinson-King, 2020). Many cases have occurred throughout the United States, especially in large urban areas. In New York City, according to Trugman (1999), over 1000 cases were reported annually.

As a result of the seeming increase in incidents, many jurisdictions have implemented laws to deter impersonation crimes. Colorado, US, for example, passed Lacy’s law (CRS § 18-8-112) after 20-year-old Lacy Miller was abducted and murdered by a police impersonator in 2003. This law made peace officer impersonation a low-level class 6 felony. According to the statute, any indication of peace officer identity theft may result in an arrest and further penalties, including but not limited to incarceration and fines. In most US jurisdictions, impersonation crime is considered a misdemeanor.

In South Africa, any individual who uses an implement that resembles police tools or uniform or falsely pretends that they are a member of the Police Service without the written permission of a National or Provincial Commissioner is guilty of a criminal offense (Salmon, 2020). In Nigeria, Section 109 of the criminal code states that:

Any person who, not being a person serving in the armed forces of Nigeria nor a member of the police forces, and with intent that he may be taken to be such a person or member as aforesaid, (a) wears any part of the uniform of, or (b) wears any garb resembling any part of the uniform of, a person serving in the armed forces of Nigeria, or a member of the police forces, is guilty of a misdemeanor.

In India, according to Chapter 9, Section 170 of the Penal Code (IPC):

Whoever pretends to hold any particular office as a public servant, knowing that he does not hold such office or falsely personates any other person holding such office, and in such assumed character does or attempts to do any act under colour of such office, shall be punished with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to two years, or with fine, or with both.

Impersonation crimes, however, may still be thought of as harmless pranks, according to some commentators (Trugman, 1999; Van Natta, 2011), despite the possible serious consequences that may result for vulnerable populations. Additionally, offenses undermine and create distrust of official authority.

This research employs descriptive statistics based on content analysis and qualitative thematic methods that explore incidents of police impersonation. Data were collected from newspaper articles on Google Alerts that involved confrontational impersonation crimes, specifically, impersonation of state and official personnel, federal officials, and law enforcement officers. The research was designed as an exploratory study that examines the events and actions associated with perpetrators of confrontational impersonation crimes to increase understanding of the seriousness of such acts. The research builds on grounded theory and offers perspectives and narratives on confrontational impersonation to add to a neglected area of criminal activity.

As previously mentioned, research on law enforcement impersonation crime is minimal. This paper fills a research gap that raises more awareness about the varieties of police impersonation crime. In the following sections, a summary of the extant literature is given, an analysis of the data is presented, and the findings are discussed.

Literature review

As mentioned previously, empirical research on impersonation crime is minimal, and the focus is limited to police impersonation. Yet, previous research indicates that this type of crime has been reported historically and globally (Gellately, 2000; Hurl-Eamon, 2005; Rennison & Dodge, 2012). Impersonation crime is appealing to many offenders because imposters feel secure in their fake persona. Their actions may be unreported because some citizens see police officials as corrupt and accept minor unethical or criminal incidents as normal behaviour. Historically, impersonators targeted vulnerable populations and intimidated them, knowing that they were apt to avoid being involved with the law (Hurl-Eamon, 2005). Additionally, as police undercover work increases, opportunities for police impersonation crime increase. Often it is easy for the offender just to flash a fake badge or card when a uniform is not needed (Marx, 1980).

Felson (2006) noted that impersonation crimes involve three tactics: scaring off potential enemies, pressuring victims to comply by intimidating them with fake police tools, and protecting themselves from bystander interference. In other words, according to Felson, impersonators use “legal behaviour to carry out illegal acts” (p. 256). As a result, this form of social identity theft reduces citizens’ trust in law enforcement, ruins the reputation of official agencies, and undermines legitimate police work (Marx, 2005). Thus, even though impersonation crimes typically target civilians, they also harm police organisations and police personnel (Walckner, 2006).

Past research has explored the motives and targets associated with impersonation crime. Gellately (2000) examined case files of police imposters (officers in the Gestapo; secret police) in Nazi Germany, providing a rare historical perspective. His research found that police impersonators tended to be individuals with selfish and egocentric traits and that this form of impersonation was used to abuse power. Police impersonation was made easier after 1933, when Germany was preparing for war and police powers were unchecked. The study, similar to Hurl-Eamon (2005) conclusions, found that police impersonators usually target vulnerable populations; in this narrative, the imposters targeted the Jewish population, and the motive was material gain (Gellately, 2000).

Walckner (2006) analysed 50 police impersonation incidents (25 police reports and 25 media reports) to explore the psychological motives behind impersonation crimes. He discovered that impersonators are typically police enthusiasts motivated by materialistic gains. Rennison and Dodge (2012) further investigated major themes and patterns in the typology of offenders in a study that scrutinised 56 police cases obtained from three metropolitan areas in the United States from 2002 to 2010. Their results showed that offenders tend to be common crooks or cop wannabes. A common motive in their study was materialistic gain; in rare cases, deviant or sexual reasons were present.

The most recent study on police impersonation by Ojedokun (2018) explored the specific factors that sustain police impersonation crimes in Nigeria. The study concluded that poor monitoring of dismissed police officers; sale of police kits (e.g., uniform, belts, badges); the corruption of some police officers; youth unemployment; and social media (cyber police impersonation) are the leading factors that promote these types of offenses. Ojedokun (2018)also argued that police imposters are likely to engage in abuse of power or human rights violations and that the crimes may be violent(e.g., kidnapping, homicide, sexual assault) or done for materialistic gain.

According to these studies, police-looking tools are easy to obtain, thus creating an effortless opportunity for perpetrators. A study in South Africa by Bassey et al. (2015) proposed using radio frequency identification (RFID) to combat police impersonation crime. The study offered a design for a RFID-based device with both tag and mini-reader integrated for every police officer and police car. Bassey et al. (2015) also recommended a novel interface called Police Identification System (PIS) to assist the police in the documentation process. The proposed identification system, however, offers no protection for potential victims and would have little or no deterrent effect. One primary goal of a police impersonator is to operate outside an agency to avoid detection. The authors’ goal to “stop police impersonation and reduce crime rate” is worthwhile but fanciful at best.

In summary, the research shows that opportunities, materialistic motives, vulnerable populations, and authoritarian desires contribute to an impersonator’s actions (Gellately, 2000; Ojedokun, 2018; Rennison & Dodge, 2012; Walckner, 2006). Thus, the empirical research shows similar results but remains limited to police impersonation. This research expands on previous work by exploring a more comprehensive range of confrontational impersonation crime and widens possible typologies.

Method

The study uses an exploratory approach to provide a descriptive examination of confrontational impersonation crime (CIC) reported in Google News articles. The research investigates incidents, offenders, victims, tools, and other variables to add to our understanding of CIC. Additionally, using Excel, descriptive statistics were tracked (i.e., location, gender) when they were available to gain insight into the demographics of the individuals involved in the incidents. The articles’ content was analysed to further grasp patterns and practices.

The data were obtained using the Google Alert email system, an internet-based news engine that gathers articles from over 50 000 news sources globally (Bharat, 2012). The Google Alert system automatically emails URL links from newspapers within the network. In this study, the terms police, impersonating, and impersonators were flagged. A total of 271 news articles from February 2016 to May 2020 were selected based on relevancy and printed for qualitative analysis and coding.

This method of data collection has its strengths and weaknesses. The strength of this approach is that it provides additional exploratory information on the topic. The data offer some insight and narratives into the perspectives of what occurs during these crimes. Another strength associated with this method is the convenience of obtaining the data. Crime data on CIC is challenging to gather because of the wide range of possible agencies and roles. However, data from news outlets are limited in generalisability and often need more demographic and in-depth descriptive details. Many of the news articles are missing details, especially information on victims that would help create a more precise profile for confrontational impersonation crimes. Also, the data gathered are limited to English-language articles from a small sample of countries.

Based on the incidents reported in the news articles, a content analysis was employed to examine confrontational impersonation crime. A content analysis approach searches text to count words or themes, despite debates over the quantitative and qualitative nature of the data, the results can be organised, for example, by words, sentences, and themes (Berg, 2007; Neuendorf, 2002; Rennison & Hart, 2019). The data were first coded quantitatively to identify available offender characteristics, incident types, and possible motives. Also, demographics counts of the geographical location of the crime, the gender of the offender, the number of offenders, and whether the impersonator is a repeat offender were tracked. These data were entered into an Excel spreadsheet.

The news articles were printed and read thoroughly by two researchers using open-coding to organise and identify pertinent data initially. Qualitative software such as NVivo or Qualtrics was not used. The thematic (axial coding) analysis was based on reoccurring ideas, labels, and similarities identified by the researchers from all the articles to gain some insight into the narratives of the different individuals involved in the cases, for instance, the victims, offenders, and law enforcement. Inter-rater reliability was strengthened based on a verbal process of agreement between the two researchers on separately identified themes. The manual coding of content for themes was limited by the need for more detailed information; however, some qualitative narrative themes emerged for selective coding.

Findings

The study’s purpose was to explore the circumstances reported in the media related to confrontational impersonation crime. Demographics information was extracted, and four major qualitative themes were identified. These themes included (a) characteristics of the incidents used by confrontational impersonators, (b) motives of the crime, (c) victim narratives, and (d) law enforcement perspectives. The content analysis of the data shows that CIC can vary in type, tools, motive, and consequences, though several patterns emerged across cases. Overall, obtaining tools to deceive victims was an easy task for impersonators. Offenders appear to easily get into character and portray the personality and authority of an official personnel in order to achieve a certain goal. Interpretation of any differences among countries is superficial, partly because of the limited geographical locations and inability to generalise based on the sample of known journalistic cases.

Demographics

Countries. Most of the news articles were from the United States, India, South Africa, and Nigeria. There also were cases reported in Pakistan, Kuwait, United Arab Emirates, Canada, Bangladesh, Australia, England, Antigua and Barbuda, Vietnam, Rwanda, Mexico, Ibiza, Zimbabwe, Malaysia, New Zealand, Brazil, Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, Uganda, Singapore, Kenya, Liberia, Turkey, and Cambodia. The data limitations render any conclusions about the frequency or type of impersonation untenable. A clear limitation of the study is that the Google Alert system is limited to these specific countries and only identifies news reports in English.

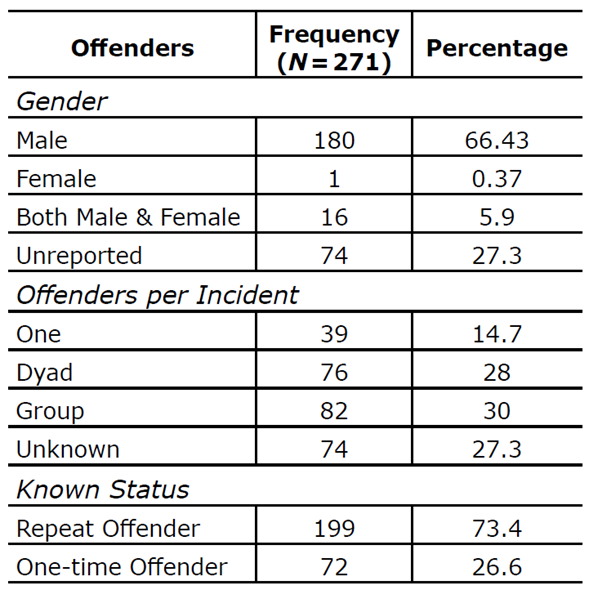

Offenders. Demographics on offenders included the gender of the impersonator, the number of impersonators per incident, and whether the impersonator was a one-time offender or a repeat offender. In 66.43% (n = 180) of the cases, the offender was a male; in one case (0.37%) the offenders were two females, while in 5.9% (n = 16) of the cases, there were both male and female offenders working together. In 27.3% (n = 74), the gender of the offender was unreported (see Table 1). Female imposters were more likely to be involved when they had male partners or co-conspirators. In several cases, the pair worked together and targeted people. In one case, for instance, a male and female couple rode motorcycles, stopped potential targets on the streets of Florida, US, and demanded DNA samples (cheek swabs) and fines.

The number of offenders per case varied. In 14.7% (n = 39) of the cases, there was a single offender working alone. In 28% (n = 76) of the cases, the offenders worked as a dyad, while in 30% (n = 82) of the cases, there were multiple (3 or more) offenders working together. In many cases, working in pairs allowed one impersonator to distract the victim while the other impersonator committed the crime. Working in groups made the crime easier to commit and encouraged further victimisation. A group of 26 Iranian-origin police impersonators in Delhi, India, for example, scammed over 100 victims, including the elderly and robbed them of cash while pretending to frisk them. In the remaining 27.3% (n = 74) of the cases, the number of offenders was unreported or unknown (see Table 1).

The data also reveal that in 73.4% (n = 199) of the cases, the impersonator was a repeat offender who had impersonated an official authority figure more than once. In some cases, the impersonators repeatedly made traffic stops and demanded money from different targets. In the remaining cases (n = 72), the offender was reported as a one-time offender (Table 1). With that in mind, the dark figure of crime plays an important role here because impersonators may get caught for their current crime but not for previous offending and thus get reported as a one-time offender. Additionally, some news articles were missing incident details or lacked information related to the offenders. It is possible that the impersonator was not arrested, the information was simply not reported or was unavailable in order to protect the privacy of the victim. Overall, however, the data show that impersonators are more likely to be serial male offenders working in a group.

Characteristics of the incident, motives, victims, and law enforcement perspectives

Characteristics of impersonations

The data were aggregated for qualitative analysis, and relevant quotes from the news articles were highlighted and studied for patterns. The following sections discusses the major themes that emerged. The first central theme was the defining characteristics of the impersonators and incidents. In other words, what official titles and jobs were being impersonated? The data shows three distinct categories: law enforcement, federal, and official or state agents. Additionally, each type of impersonation category used specific methods or tools to deceive the victims. The following sections discuss these categories and practices in more detail.

Law enforcement agents. The most common type of confrontational impersonation was law enforcement agents (83.4%; n = 226). This category included impersonating police officers, detectives, sheriffs, Security Weapon and Tactics team (SWAT), and security officers. These impersonations occurred mostly in the United States, India, and Pakistan. This type of confrontational impersonation is perhaps the most common because law enforcement impersonators are more likely to engage with the public, thus creating a more plausible excuse or opportunity to commit illegal acts and be caught.

The data show that impersonators use law enforcement-related tools that include vehicles (cars/motorcycles), emergency car lights (red and blue), clothes (fake uniforms/vests/belts), counterfeit badges, weapons such as guns or batons, handcuffs, phones, radios, speakers, and horns to mislead people. Offenders either used one of these tools or different combinations thereof to develop their character. In most cases, the offenders used emergency lights placed on their cars and pulled over random individuals. Some of these impersonators wore a police uniform or a T-shirt with the word ‘Police’ on it. The more prepared offenders pulled out a fake badge and a weapon to further intimidate their victims. A police officer from Cape Town, South Africa, noted that:

This type of crime comes in three forms. First, is fully clothed police officers openly committing robberies, hijacking, and bribes; second, people impersonating police officers who have all the markings and equipment of being real police officers; and third, those driving in private cars pretending to be cops (Cruywagen, 2019).

In several cases, the impersonators would use a fake badge, pretend to be undercover law enforcement officers, and target individuals on the streets or families in their homes. In other cases, offenders used phones to call and defraud victims. In one case, for example, a group of impersonators in Colorado, US targeted registered sex offenders in their area by impersonating a sheriff’s deputy and asking for a fine to be paid.

Federal agents. Federal agent impersonators were less common than law enforcement impersonators comprising 8.5% (n = 23) of the cases. This category included offenders primarily in the United States impersonating agents from the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), Internal Revenue Service (IRS), U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and the army/military.

The most common tools used in federal agent impersonation were bogus identifications, badges, forged documents, clothes (uniforms), and phones. Several cases, mostly reported in Nigeria and South Africa, involved offenders using the uniforms of former army/military members and impersonating military/army personnel. In nonconfrontational cases, impersonators used phones to call victims and ask for their credit card information for tax purposes or to take them off a wanted list. In a few cases, offenders impersonated ICE agents and threatened to report undocumented immigrants. In one elaborate guise using the identity of an ICE agent, a victim was subjected to DNA collection. At the same time, with a fake prostitute working in tandem, the victim’s wallet and personal items were collected. The impersonator used a radio, video camera, and Q-tips to complete the ruse.

Official/State agents. The last category of impersonators is the official and/or state agents’ category, making up 8.1% (n = 22) of the data. This category included impersonators of agents from the Child Protective Services (CPS) or the Division of Family Services (DFS), state house staff, security personnel, COVID-19-related personnel, and others. The most common tools of deception are similar to the federal agents’ tools, including forged documents, fake identifications, and badges. In several cases, offenders impersonated CPS agents and targeted families by performing phony home visits and kidnapping children. In one case in the US, for example, the mother of a child, victim of an attempted kidnapping, had an uneasy feeling when a CPS impersonator targeting families in the area knocked on her door. Another CPS impersonator kidnapped a 7-month-old child from his home in Ohio, US. Families in the neighborhood reported being in contact with the CPS impersonator days prior to the incident.

In other instances, perpetrators impersonated state agents to solicit favours from government agencies (e.g., employment, security footage, information). In Abuja, Nigeria for example, a pair of State House impersonators used forged letters and offered employment opportunities to people who paid. As a result, government and private agencies were directed to do thorough background checks on documents before accepting them.

COVID-19-related impersonations. The COVID-19 pandemic appeared to create new opportunities for confrontational impersonations. These offenders impersonated police officers, nurses, and COVID-19 testing personnel. This type of confrontational impersonation falls under law enforcement and official agents. In these cases, offenders either made random traffic stops for violating stay-at-home orders or they created fraudulent COVID-19 testing sites, or in some cases, pretended to be experts in the medical field and sold fake Corona Virus equipment and supplies. The news articles suggest that the increase in this type of impersonation stems from unemployment and financial need. Older people in different communities were vulnerable targets to the COVID-19-related impersonators. In one US city, the police warned that “criminals focus on the life and financial position of seniors” and that caretakers and family members “should pay close attention to their seniors during this time.”

Recognising the emerging types of confrontational impersonations, many law enforcement agencies have called for more regulations and punishments for this type of crime. News articles also provided readers with tips on how to avoid COVID-19 related victimisation. For example, some news articles informed the public about the real COVID-19 testing sites and local COVID-19 regulations.

Motives

The second major area identified was the motive of the crime. Prior research (Gellately, 2000; Ojedokun, 2018; Rennison & Dodge, 2012; Walckner, 2006) shows that police impersonation crime is typically motivated by materialistic means and/or a psychological need for power and authority. This study on impersonation crime supports previous findings that the most common crimes associated with impersonation were materialistically driven or authoritarian based. In fewer cases, violence or cheating was also associated with the impersonation crime. Some reported cases combined at least two to three of the listed motives. In the remaining cases, the motive was unknown or unreported.

Materialistic motives. The data show that in 45.1% (n = 122) of the reported cases the motive was to gain some materialistic benefit. The confrontational impersonation crime was accompanied by either theft, home invasion, phone scams, fraud, or extortion. Offenders often lured victims by impersonating trusted personnel such as a police officer or an official agent to get either money or valuable objects (e.g., jewelry, electronic devices, drugs). A group of serial offenders, for example, targeted individuals in different cities throughout England by impersonating police officers and claiming to investigate “compromised” bank accounts and asking for large money withdrawals in order for them to address the issue. In another incident, police impersonators robbed a Chinese businessman of $14 million, his licensed firearm, and several rounds of ammunition in Massachusetts, US. While in another incident, a group of police impersonators invaded homes and robbed families of money, guns, and prescription pills.

Power and authority. The second most common motive reported is the need to establish power or authority. In 10.7% (n = 29) of the reported cases, offenders would mimic powerful positions in order to gain access to security recordings, solicit favours, steal victim information, or enforce stay-at-home orders during the COVID-19 pandemic. In many reported cases, the victims stated that the offender only requested to see an identification and asked some questions then let them go. This behaviour may indicate the need for power and authority since no further crime took place. In one case reported in Durban, South Africa two military impersonators wearing uniforms were spotted at a funeral. One police impersonator in Florida, US, stopped a nurse for “speeding” and asked to see her driver’s license. The police impersonator “told the nurse she could ‘consider this a warning’ and handed her license back to her after studying it.”

In another incident in Michigan, US, juveniles with stolen guns and fake police red and blue lights on their sports utility vehicle stopped a woman on the street and asked to see her driver’s license and vehicle paperwork. When she questioned the stop and notified them that she has a relationship with “someone in law enforcement,” the juveniles told her to have a good day and drove off. Additionally, a group of impersonators was arrested in Michigan, US after impersonating first-responders including police officers and fire-fighters for at least three years. When asked about their motive, they stated that they were trying to serve their community and help out. Sometimes they were the first to arrive at crime scenes and “the real police would ask them to perform tasks.”

Violence. In a small number (8.5%, n=23) of the cases, the motive of impersonation was to commit a violent crime. The violence included homicide, kidnapping, assault, sexual assault, or threatening the victim with a weapon. In one violent incident in Texas, US, three men held a family at gunpoint during a home invasion. They also “ransacked the home and pistol-whipped one of the family members.” While in Pennsylvania, US, a pair of police impersonators stole a car from a couple and kidnapped the female victim. They later dropped her off at a police station. In an unfortunate chain of violent offenses in cities in Indonesia, a pair of police impersonators stopped couples with the intention of theft and rape:

Brandishing a gun, the thugs ordered the young lovebirds to hand over their mobile phones. The two were directed away from the road and into a bushy area of vacant land. The boyfriend was tied up with a jacket and ordered to remain silent if he wanted to live. The bandits then raped the girlfriend in front of him. The boyfriend shouted, only to be beaten and gagged. The two men then stole the couple’s motorbike.

In some cases, the violence of the incidents took interesting turns. For instance, in Kelantan, Malaysia, a pair of police impersonators and real police officers were involved in a shoot-out that resulted in the death of the impersonators. While in Guerrero, Mexico, a pair of police impersonators wearing fake police uniforms were found dead in their car. Violent cases usually included the use of a weapon (as a threat) or sexual assault.

Victim Perspectives

Although victim information is limited in news articles, a theme that emerged in this research was victim perspectives towards impersonation crime. Some victims expressed feelings of fear, trauma, and disappointment. A victim stated: “I am still disturbed about it, and every time I become more worried about the damage the fraudster could be doing.” Another victim expressed her fear for her family’s safety: “I can’t even feel safe in the place that I’m living in.” Similarly, one victim shared his anxiety and frustration with the media after his home was invaded and robbed in Florida, US.

We don’t know if these men will come back or what plans they have. They obviously used the F.B.I. Lettering on one of their bulletproof vests to get in and then they kidnapped my workers--a construction man and a cleaning lady--and put them in the bathroom. I would like the public if they recognize to call in about them. These are bad men. And I am offering a $1,000 reward of my own in addition to what Crime Stoppers is offering. I hope people will do the good thing and get these people off the street so nobody will have to go through what I went through.

Individuals who were victimised by impersonators describe them as intelligent and believable. One victim described the impersonator as “very sneaky, clever, mischievous” and another victim called a group of impersonators “very good actors and very convincing” especially when they showed a badge. Some victims even believe impersonators are “mastermind criminals” because of their manipulating nature, which targeted many individuals. They also noted that this level of planning was not easy and required time and resources. A victim stated that it was “clearly a well-planned and sophisticated conspiracy. There were a large number of victims and it was over a sustained period.”

Many victims had an uneasy gut feeling that the impersonator was not a real official agent. They would typically report feeling like something was off. In these cases, the victims waited to be in a safer space and called the police immediately. A victim commented, for example, that she “pulled into a public place making sure that there are other people around” when she was suspicious that the police officer was an imposter. Another victim targeted for his money told the police that he knew the badge he was shown was fake but was threatened by the presence of the weapon and complied until it was safe to call for help. Many victims complied with the impersonator’s orders and believed that the impersonator was a corrupt yet authentic person.

Law Enforcement Perspectives

Since the most common type of impersonation in this research was law enforcement, a major theme was the officials’ perspective on confrontational impersonation crime. In many cases, law enforcement agents described this type of crime as an opportunity that leads to serious consequences, including physical and psychological trauma. “It’s not going to be the first or last time we see someone impersonating a police officer and that’s very dangerous” noted a law enforcement agent.

One police impersonator tried to stop a commissioner and former officer Joe Martinez in Florida, US. Officer Martinez noticed that the lights on the fake police car were not the “standard police lights” and proceeded to search the car and found a gun. He responded by saying:

I thank God it was me that they tried to stop for the simple reason that I know more or less what could be going on. Could you imagine a young person or elderly person who just got their license, they probably would have stopped and then what could have happened?

Law enforcement agents usually express their frustration with impersonators by assuring the public that the offenders will be arrested and charged accordingly because this type of behaviour is “unacceptable.” A law enforcement agent stated that “all of us in law enforcement want to do anything we can to eliminate this individual from being out there and doing this type of action.” Many police departments noted that they are taking this type of offense seriously. They said, “these issues are being treated with the greatest level of importance and urgency, and the investigations are ongoing.” Understandably, in many incidents, law enforcement agencies took umbrage at this type of crime because it damages the image of policing. Law enforcement agencies aim to serve and protect rather than harm. A police officer said: “We as a police department try to make the people who live in our town, also travel through our town, feel somewhat safe. When something like this happens, we do take it very personal.” Another police officer indicated that “it makes it more difficult for the real police to do their jobs.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, there was an increase in frustration due to the risk impersonators created for official agents and the public. A law enforcement agent warned that “criminals will exploit any opportunity possible to defraud innocent and vulnerable people out of their cash - and it’s incredibly disappointing to see that some are taking advantage of the COVID-19 outbreak for this purpose.” Another law enforcement agent commented:

They want to be in some position of power. It just gives them an opportunity to go out and try and assert some authority or pretend to assert some authority. No good cop likes someone pretending to be a cop.

In general, law enforcement agents see this type of crime as an offense of opportunity that targets vulnerable populations, consistent with prior research. As Lieutenant Al-Shamsi from the Sharjah Police Department in the United Arab Emirates stated, “Suspects were targeting people who did not have adequate knowledge about police procedures or did not think of asking the men to show them their police identity card.”

Finally, a typical response from law enforcement was to warn the public and provide advice and tips for avoiding victimisation by impersonators. A law enforcement agent encouraged “members of the public to please remain vigilant and to share our advice with their families so we can prevent further people from falling victim to this terrible scam.” Another law enforcement agent told the public that police “don’t take people out of their car until some point later in the stop. Unless it’s necessary to get them out of the car, we like to keep them in the car because you can watch them a lot easier.” The most common suggestions from law enforcement include the following:

If you think something is suspicious, trust your instinct and call the police.

If you feel like you are in a dangerous situation, comply until you are safe enough to call for help.

Familiarise yourself with law enforcement uniforms, tools, and badges.

Ask for the agent’s badge or identification number. Police officers also usually wear a name tag.

Emergency lights on police cars should be built into the windows.

Never give personal information over the phone; not to police, not to IRS, or anyone claiming to be an official agent.

Law enforcement agents would never ask you for your credit card information over the phone.

Use the internet to double-check departments’ phone numbers.

Discussion

Confrontational impersonation is a unique type of crime that seems simple, though a more thorough examination of the characteristic and situational complexities makes identifying, categorising, and understanding this behaviour a challenge that needs to be addressed. The present study was able to identify a variety of approaches primarily associated with enforcement agencies. Additionally, motives appear to be financial gain or authoritarian ego enhancement. Confrontational impersonation also includes implements or techniques commonly used to convince victims that the interaction is legitimate. Thus, identifying a single theoretical framework that explains this area of crime represents a difficult task (Rennison & Dodge, 2012). This study addresses impersonation crime from a grounded inductive perspective using available media reports and existing conceptual, theoretical frameworks that emphasise opportunity. This initial exploration serves as a basis for investigating future explanations and elements of confrontational impersonation crime. Future research that focuses on a single country or geographical area with data that offer more exhaustive details is necessary to increase our understanding of these events.

Several previous studies have identified possible theoretical explanations which utilise rational choice and situational theories. Ojedokun’s (2018) research, for example, proposed that situational choice theory (Cornish & Clarke, 1987) be applied to impersonation crime. Ojedokun (2018) also suggested that impersonators employ a rational choice approach that weighs the opportunities, risks, costs, and benefits associated with the offense. The choice to commit the crime, more importantly, is linked to enhanced opportunity that requires looking beyond the criminal event, that is, the inseparability of the offense and offender.

Routine activity theory identifies motivated offenders who make the choice to commit an offense in the presence of suitable targets and the absence of capable guardians (Cohen & Felson, 1979). Routine activity theory, despite its popularity, appears to lack explanatory power for confrontational impersonation crimes. As noted by Rennison and Dodge (2012), the impersonator assumes the role of capable guardian, thus changing the structure of the criminal event. Rennison and Dodge (2012) argued in police impersonation cases, the offender adopts two roles in the commission of the crime, which fails to fit a routine activity framework.

The results of this study show that opportunity is created by offenders who often are motivated by power, typically in the form of an authoritarian persona who seeks financial gain (see also, Rennison & Dodge, 2012). Posing as a capable guardian indicates that offenders remain masked to engage in criminal behaviour. Unfortunately, confrontational impersonators may use mimicry and masking to engage in a wide variety of crimes (e.g., mass shootings, terrorism, theft, kidnapping, sexual assault). These offenders also can deceive almost anyone, particularly vulnerable populations that are more susceptible to fraud and may be unaware of their victimisation or afraid to report it. Overall, three features of impersonation crime are most apparent: mimicry, masking, and opportunity.

Rennison and Dodge (2012) noted that Felson’s (2006) theoretical explanation of crime and nature represents a useful framework for understanding police impersonators. According to Felson (2006), Kapan’s Müllerian mimicry occurs when different species use mimicry behaviour to alter their physical appearances in order to deter potential threats from predators (see also, Kapan, 2001). Jones (2014) argued that predatory and parasitic deceptive behaviours using mimicry-deception might be short-term efforts such as theft or long-term white-collar crimes. Confrontational impersonators usually commit short-term offenses over a long expanse of time though, in some cases, the deception may resemble complex white-collar crimes.

A confrontational impersonator alters their physical appearances to deter possible threats of capture and create opportunity to become the offender. “Police impersonators are criminals who take on the “colouration” of legitimate law enforcement officers for protection as successful predators. In this clever reversal, the offender is mimicking the ‘good-guy’” (Rennison & Dodge, 2012, p. 521). This aspect of mimicry was apparent in the case of the mass shootings in Canada and Norway.

Masking, which overlaps with mimicry, allows the impersonator to hide behind a chosen authoritarian persona. Using tools such as badges, weapons, and uniforms, the impersonator elevates their status to manipulate the victim into compliance. In a literal sense, the confrontational impersonator intentionally designs a costume to achieve mimicry. The goal to model the behaviour of an “official” requires the costume, attitude, and posturing to achieve mimicry and masking. The influence of media portrayals demonstrates the power of an easily copied occupation. Also, as noted by Marx (1980), undercover work with many officials in plain clothes simplifies the task of impersonation. Confrontational predators who rely on telephones are engaging in an additional layer of protection. Benson and Simpson (2018) persuasively summarise the relationship between techniques and opportunity:

Criminal opportunities are exploited through the use of particular techniques. That is, in order to take advantage of a criminal opportunity, the offender often has to know how to use a particular technique. Indeed, sometimes it is the availability of a technique that determines whether a situation presents a criminal opportunity or not. (p. 83)

Confrontational impersonation crime is typically perpetrated by blue-collar or street level offenders who create their opportunities by establishing a position of power using a deceptive occupation to target victims. Opportunity is an important element of all criminal events (Benson & Simpson, 2018; Felson, 2002), and deception is central in explaining the creation of opportunities for impersonation crime. According to Benson and Simpson’s opportunity perspective, “deception is the advantageous distortion of perceived reality” that can be achieved using “embellishment, mimicry, and hiding (p. 239).” Impersonators embellish their authority using the guise of mimicking legitimate enforcers or other occupations. Similar to white-collar crime the offenders often remain hidden, and victims fail to recognise they have been duped (Benson & Simpson, 2018).

Opportunity is central to understanding confrontational impersonation crime. In rare cases, except for many white-collar crimes, criminal opportunities may result from numerous macro and micro theoretical variables (e.g., social disorganisation, social bonds, low self-control, or learning theories). In fact, opportunities are ubiquitous: that is, the “lure is everywhere” (Benson & Simpson, 2018). The confrontational impersonator will not be viewed as suspicious, despite the resulting erosion of trust as increased victimisation occurs. These impersonators will create opportunities to engage in traffic stops, approach people on the streets, or target homeowners. Other confrontational impersonators use telephones to directly engage and target victims, which falls outside the realm of computer crime (i.e., cyber fraud committed by nonconfrontational impersonators).

Confrontational and nonconfrontational impersonators take advantage of mimicry and use easily available tools to mask their real identities. These actions create opportunities for an assorted range of criminal behaviour. Yet, unexplored areas that may further contribute to theoretical musing are two essential considerations. First, incidents in which the crimes are white-collar (e.g., Frank Abangnale) as the occupational standing is designed to be more powerful and the financial gain higher may involve unique aspects for the impersonator.

Second is the need for further understanding of how social situational opportunities like COVID-19 increase the opportunity for confrontational impersonation fraud.

Conclusion

Confrontational impersonation crime is a problem that may victimise many individuals and represents a dark figure of crime. Unfortunately, research on this type of crime is scarce and limited to police impersonation, neglecting federal, state and official agents. This research was designed to provide additional insight on the verities of incident characteristics, motives, and perspectives towards confrontational impersonation crimes and shed light on perceived patterns.

Overall, the study revealed that confrontational impersonation crime is more serious than typically acknowledged. In many cases, it traumatises the victims physically and/ or psychologically, undermining their trust in law enforcement, damaging the image of law enforcement, state/official agents, and federal agents. In most cases, the motive behind this type of crime is materialistic, thirst for power or authority, and, in rare cases, violence. Impersonation crimes with materialistic loss or violent tendencies lead to strong reactions from the public because the incident details get more coverage and attention from different news outlets. In addition, impersonators find it convenient to commit this type of crime because people usually trust official personnel in the community. According to the data, the tools of deception are easily accessible, which makes this type of crime expedient for many offenders.

Not only is this type of crime dangerous for the reputation of official personnel, but it can also have an impact on international relations. For instance, the danger of federal agent impersonators is serious because of the political implication that involves international links and jurisdictions. This type of case may lead to tensions in areas where agents of actual power are put in threatening situations. Although these crimes might be seen as mere pranks in the eyes of individuals in power, they might spread rumours and false news that eventually negatively affect the public’s perception. Thus, federal agent impersonation calls for more direct and severe policies that should attempt to minimise this crime; especially when bold statements are made by the impersonators. With the power of social media, it may become difficult to distinguish between real and false identities.

Strengths and limitations. This study explored a relatively large sample size compared to past research efforts. Using a qualitative and grounded theory approach we identified patterns and a possible theoretical framework. The data also contribute to the extant research by offering more profound knowledge and perspectives. The methodology and data employed in the study give a unique narrative on confrontational impersonation crime. This research is the first to provide a wider array of incidents. The study explored different types of impersonation crimes rather than focusing on police impersonation, therefore, widening the scope of this crime’s research.

Limitations in this study are ironically also related to data. As stated previously, the data gathered for this study is from news articles obtained from the Google Alert system. News articles supply research with information on a given topic, yet they also lack some information that may be crucial. For example, the news articles in this study may be limited only to countries that grant Google access. Also, these news articles rarely provide detailed information, the full story, or the outcomes of the crime (e.g., victim information, charges, sentencing). Thus, the research conclusions are constrained by the quality and content of the data collected.

Furthermore, since the dark figure of crime plays a major role in this type of criminal activity, only media-reported cases were analysed. The unavailability of statistics makes it difficult to understand the severity and frequency of this crime. With this information missing, policy decisions become a more challenging process. Although patterns and demographics can be established, it is difficult to protect the public from impersonators as they find creative and improved ways of engaging in deceitful acts.

This study shows that confrontational impersonation crime is potentially a widespread issue targeting many individuals. Yet, the current study can only serve as a baseline for future research. Though some themes and patterns were identified, it is only a start, especially since information on this criminal activity is rare. The emerging attention may encourage other criminologists and experts to conduct further and more detailed studies. Future research can look at different methods of deterring and protecting the public. The easy access to tools, for example, may require further legislation that creates stricter laws.

The findings also indicate the importance of keeping the public informed. Especially when impersonation can take many forms and layers and may be prone to improvements with the evolving technology. That said, future research may also address the tips law enforcement give the public. It remains to be seen whether these techniques are helpful. Different cultural perspectives towards authority and this type of crime may heavily influence deterrence methods. Potential future research can benefit the field by comparing law enforcement agencies’ policies and regulations to determine what can help deter confrontational impersonation crime.

Additionally, another area of research may explore how major events in the community can influence this type of criminal behaviour. This study identified new types of confrontational impersonations related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Will conditions of normlessness lead to more opportunities for confrontational impersonation? This question mirrors Gellately’s (2000) research on the time period when Germany was preparing for war and opportunities for police impersonation expanded. How can the community be more aware, prepared, and protected in these circumstances?

Finally, previous work shows that targets are often members of vulnerable populations. However, this research failed to establish any patterns or profiles for victims due to the lack of information on victimology. The only victim information available was gender and whether the victim was part of a targeted group. In a high number of cases the victim was a single male. In some cases, the victims were a couple or a dyad. Additionally, a small number of families were victimised in their homes. Future research might prioritise data related to victims of confrontational impersonation crime so that more appropriate policies and regulations are implemented.

Confrontational impersonation crime is distinguished from cybercrime, by employing face-to face means to deceive individuals. Overall, the study found that confrontational impersonation crime varies in type, motive, and consequences. Yet, the most common impersonations were law enforcement agents, and the motives were materialistic gain and authoritarian power. Impersonators use easily obtainable tools such as vehicles, red and blue lights, badges, uniforms, weapons, fake identifications, and documents to deceive their victims. Consequently, confrontational impersonation crime can lead to widespread damages, including mistrust in law enforcement and official personnel, psychological and physical trauma, theft, and violence. Further investigation of the role opportunity, mimicry, and masking play in confrontational impersonation crime may contribute to detection and deterrence efforts.