INTRODUCTION

Coronary artery fistula is a rare condition defined as an abnormal communication between a coronary artery and a cardiac chamber (coronary-chamber fistula) or any segment of the systemic or pulmonary circulation (coronary arteriovenous fistula). The most frequent etiology is congenital malformation, which develops during the muscular and arterial organization embryonic stage, between days 31 and 39 of embryogenesis; the development of coronary arteries occurs during the advanced phase of heart morphogenesis. Since day 31, the spongy myocardium of the embryo becomes progressively massive, while subepicardial canicular networks, precursors of the coronary artery system, are formed. On day 35, the coronary buds of the aorta develop, and join the subepicardial network. Fistulas are caused by the persistence of intratrabecular spaces in embryonic sinusoids. 1

Coronary artery fistulas can be acquired and appear in tumors such as hemangiomas, in rheumatic or iatrogenic heart disease, after cardiac surgery, in transplant patients or they can also be post-traumatic or secondary to invasive cardiac procedures (implantation of pacemaker, endomyocardial biopsy or coronary angiography). 2 Nearly half of patients with coronary fistulas remain asymptomatic, while the other half develop congestive heart failure, infective endocarditis, myocardial ischemia induced by coronary steal or rupture of the aneurysmal fistula. 3 Its incidence is 0.20.6% in angiographic series and 0.002% in the general population. 1

Frequently, coronary artery fistulas are found in patients aged between 30 and 76 years, with a mean of 71±14 years, which may be related to the age at which coronary angiography is most commonly performed, with a male-female ratio of 1.9:1. 4 They can also be associated with other congenital anomalies. Although there is no uniform consensus on the most common site of origin and termination, reports describe that the left coronary artery is involved in 35% of cases, while the right coronary artery is involved in 55% of cases, and both in 5%. 5 It can be drained to another blood vessel or cardiac chamber, more frequently to the right cavities (90% of the cases), and to the left ventricle in only 3% of the cases. 1

CASE PRESENTATION

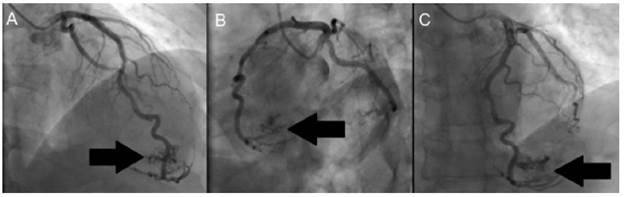

This paper reports the case of 52-year-old male patient, from Bogotá D.C., without ethnicity, and architect for profession. He presented with a history of dyslipidemia, and consulted due to a 6-month history of episodes of sharp retrosternal chest pain that radiated to the back and neck, lasting less than 5 minutes, associated with moderate efforts and attenuation at rest. He also showed progressive deterioration of his functional class. Physical examination was normal and electrocardiogram showed sinus rhythm with a heart rate of 70 bpm, with changes compatible with necrosis in the lower and lateral sides. Transthoracic echocardiogram showed left ventricular ejection fraction of 58%, with segmental alterations in contractility due to severe hypokinesis in the apical lateral, apical infarction and concentric remodeling of the left ventricle with a non-mobile image of an 11x9mm calcium refringence suggestive of a small organized thrombus. For this reason, a myocardial perfusion with pharmacological stress (dipyridamole) was performed, which was negative for myocardial ischemia, with lower wall necrosis in the middle and distal segments. Figure 1 shows a severe perfusion defect in the middle and distal segments of the inferior wall, not reversible, and with mild hypokinesia; the estimated area of necrosis is 5-7% of the total myocardial mass.

Source: Document obtained during the study.

Figure 1 Myocardial perfusion test with pharmacological stress.

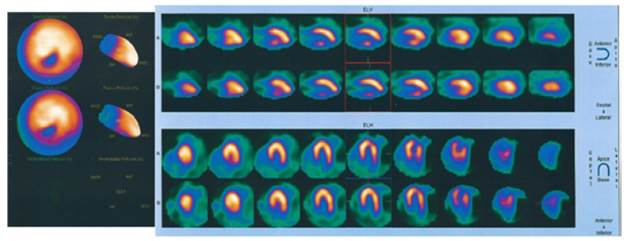

Then, invasive stratification was performed by left ventriculogram and selective coronary angiography (Figure 2 and 3), in which a dominant right coronary system with epicardial coronary arteries, without obstructive lesions and presence of a fistula of the distal anterior descending artery to the left ventricle was found.

Figure 2 shows extravasation of contrast medium into the apical territory irrigated by the anterior descending artery, while, in Figure 3, diagnostic injection on the left coronary artery shows posteroanterior projections (ARC 18°, RAO 25°) (Figure 3A), left oblique with caudal angulation (CAU 20°, LAO 49°) (Figure 3B) and left oblique with skull (CRA 18°, LAO 8°) (Figure 3C). Extravasation of contrast medium is also observed from the anterior descending artery to the left ventricle (black arrow).

Considering that the findings ruled out significant coronary lesions, the patient was discharged the same day and cardiac nuclear magnetic resonance was requested as a complementary study for better anatomical characterization of the coronary fistula, in order to define management. The patient did not attend follow-up consultations.

DISCUSSION

This case is reported given the low frequency of this pathology and its form of presentation: precordial pain similar to angina, with infarction, epicardial coronary arteries without obstructions, and coronary fistula of the anterior descending artery to the left ventricle by means of coronary angiography.

Coronary fistulas that cause coronary disease or result in myocardial infarction are rare. The most prevalent symptom is angina pectoris; heart failure is less frequent and can cause infective endocarditis, thrombosis, embolism or arrhythmia. 6,7

In the study by Wilde & Watt 8, 141 cases were reviewed, finding that 81 (57.4%) were asymptomatic, 35 (24.2%) presented dyspnea and 27 (18.4%) reported precordialgia. For Uyar et al.9, the symptomatology of the fistulas that drain to the left ventricle can be similar to the symptomatology of aortic regurgitation.

Coronary fistulas can be congenital or acquired; they can also be associated with another congenital heart disease in 20-45% or be isolated in 55-80% of cases. 10 Studies have shown that its origin is the right coronary artery in 52-60% of the cases, the anterior descending artery in 30% and the circumflex artery in 18%. 11,12 Likewise, about 90% of the fistulas end up in the right cavities, being more frequent in the right ventricle (40% of the cases), followed by the right atrium, coronary sinus and pulmonary trunk. 12 The drainage of a coronary fistula to the left ventricle is very rare. 1,9

The pathophysiological importance of coronary fistula relates to the volume of blood flowing and the pressure gradient through communication. Myocardial ischemia may occur due to decreased blood flow at points distal to the fistula or coronary steal. 6 If the fistulas are long or multiple, the intracoronary diastolic perfusion pressure could drop progressively below the critical level and a major short circuit may occur from left to right. When this occurs in situations such as physical activity, it leads to an increase of myocardial oxygen demand, producing myocardial ischemia beyond the origin of the fistula; in other cases, signs of heart failure or pulmonary hypertension may be expected. 13 Coronary steal is the main cause of ischemia, but if there are high pressures in the left ventricle, it may not cause myocardial ischemia in relation to absence of elevated ventricular end-diastolic pressure. Yamanaka & Hobbs 14 found that myocardial infarction, seen in 9 of 51 cases, was caused by coronary fistulas.

Clinical symptoms and electrocardiogram may be helpful for diagnosis, especially in patients with long fistulas. Electrocardiographic signs may be similar to those of left ventricular overload or dynamic changes of the ST segment.

Doppler echocardiography in adults has low sensitivity, so most coronary artery fistulas are diagnosed incidentally during cardiac catheterization. Coronary angiography is not only useful to establish a diagnosis, but also to determine the type of intervention that may be necessary. 9 Some other diagnostic methods such as cardiac nuclear magnetic resonance, transesophageal echocardiography and multidimensional computerized coronary angiotomography have shown benefits. 14 Among them, multidimensional computerized coronary angiotomography has been widely used as it is non-invasive and provides three-dimensional visualization that helps delineate better the anatomy of the coronary arteries. Lim et al.15 have shown that multidimensional computed coronary angiotomography detects anomalies in coronary arteries at a higher rate than traditional coronary angiography.

In children, spontaneous closure of coronary fistulas has been reported 16, being less frequent in adults. 17 In general, asymptomatic fistulas without association to other anomalies do not require immediate treatment, but fistulas with clinical relevance, symptomatic and large do require short-term treatment. 18 Indications for treatment include the presence of a large left-to-right short circuit, left ventricular volume overload, myocardial ischemia, left ventricular dysfunction, congestive heart failure, and prevention of endocarditis/endarteritis. 12

The objective of the treatment is to provide normality in the coronary circulation by means of occlusion of the fistula. 3,6 Surgical closure methods are associated with low morbidity and mortality and good short and long term results have been described 18; however, myocardial ischemia or perioperative infarction has been described in 5% of cases. 9 For this reason, the use of surgical procedures has decreased considerably and percutaneous closure has become the alternative of choice. Occlusion of the fistula with coils, injection of alcohol and removable balloons are some of the percutaneous techniques. 9,15 The risks posed by the latter procedures are rare; however, periprocedural infarctions, migration of coils to the coronary circulation, deflation of removable balloons, transient changes in the T wave and transient branch hemiblock have been described. 10

CONCLUSIONS

The presence of a coronary fistula may be an incidental finding in coronary angiography or aortogram in a patient with clinical manifestations of coronary insufficiency. Initial noninvasive complementary tests performed in patients with clinical signs of myocardial ischemia allow suspecting their presence in some cases.

To diagnose a coronary fistula, coronary angiography continues to be the most accurate diagnostic test; however, other non-invasive diagnostic methods have shown good results and could even replace this method in the future.

The therapeutic approach to coronary fistula should consider their anatomical and physiological characteristics to define whether they require management and whether it will be percutaneous or surgical. Short-term treatment benefits those patients who are symptomatic or at risk of complications such as coronary steal, aneurysm or significant intracavitary short circuit, with or without evidence of myocardial ischemia.

Findings of coronary artery fistula originating in the anterior descending artery and leading to the left ventricle are very rare in a coronary angiography, as described in the literature. In this case, without an MRI, closing the fistula by transcatheter aortic valve implantation would be recommended given the characteristics of the fistula in the angiography, because it is symptomatic and because of coronary steal. Collecting better casuistry for the study of this physiopathology, its presentation and results after treatment is expected in the future.