Introduction

In recent discussions, it is possible to notice that education theories have started to move from a teacher-centered perspective, in which students used to be passive subjects who received knowledge from teaching as a cause -effect phenomenon - also known as banking teaching (Freire, 1997a) - to a student-centered perspective, in which students are the protagonists of their learning process. They do not necessarily learn because the teacher teaches. There is nothing wrong with these perspectives, but the latter was a big twist in how education was being conceived. The student-centered perspective was a juxtaposition to the very first ideas about education.

When focus was placed on the other side of the coin (the student), researchers found that there are some flaws in several dimensions that are critical in students’ education, namely 1) the interactions between family and school, 2) the relationship between teachers and caregivers1, 3) English for academic purposes only, 4) teaching English in isolation from the context where the student lives (Bolaños et al., 2018), and 5) the hidden agendas behind the teaching of English (Council of Europe, 2001; Shohamy, 2006; Shohamy, 2009; Maturana, 2011; de Mejía, 2012). These problematic situations make students’ education more difficult and less enjoyable. Therefore, the problem studied throughout this research has to do with the impoverished relationship between schools and families to strive towards education goals, specifically English education goals.

In essence, learning communities aim to claim the role of people’s artisan knowledge (De Sousa, 2018). This means that the education process starts by taking that artisanal expertise to reach scientific knowledge (Elboj et al., 2018; Freire, 2018; Buslón et al., 2020). In other words, learning communities are under the impression that educational actors ought to be knowledge constructors from and for their communities (Flecha & Puigvert, 2002; Flecha et al., 2003; Cifuentes & Fernández, 2010; Díez-Palomar & Flecha, 2010). Likewise, foreign language education relies on the epistemological view that one assigns to it (Hymes, 1992; Maturana, 2015; Mart, 2018). Language can be seen as a structure, a means to communicate, an imposition, or a situated approach to face social problems while acquiring knowledge about the language (Barriga, 2003; Peláez & Usma, 2017; Usma & Peláez, 2017). In this sense, the stance adopted and proposed in this paper is the latter. Thus, it is possible to comprehend that learning community projects represent a twist from traditional and hegemonic approaches to a situated and community-driven approach that leads to contextualizing practices associated with English communicative competence. The Learning Communities project is an ideal proposal to address the problems regarding joint work by schools and families - even more, by schools and the rest of the community in which the school is located.

Methodology

A study’s methodology can be understood as the theory that guides the action. It is related to the way in which research problems are approached and answers are found or constructed; “it is applied to ways of doing research” (Galeano, 2018, p. 13, self-translated). In this sense, “there is no methodology without epistemological assumptions, nor epistemology without methodological support - both are tensed in a dynamic relationship” (Ripamonti, 2017, p. 95, self-translated). Considering this fact, it is essential to unveil the ideology that promotes the action, the methodology. According to this reflection, this paper adopted a qualitative approach and an interpretive paradigm, with a descriptive scope, as guidelines to study learning communities and their relationship with the development of English communicative competence. The implemented strategy was document research. Through this document research on systematizations carried out with regard to past and current events, it is recognized that the present has something to do with the past, and that, simultaneously, it houses the seed of the future.

Although document research was merely taken as a technique in its beginnings, it is herein conceived as a strategy. That is to say, it has to do with “project design, gathering information, analysis, and interpretation” (Galeano, 2012, p. 114, self-translated). The reason for adopting such strategy to approach the object of study is that documents and texts are conceived as something that “can be ‘interviewed’ through the questions that guide the research, and they can be ‘observed’ with the same identity with which an event or a social fact is observed” (Galeano, 2012, p. 114, self-translated). Additionally, two techniques were used to carry out this work: document review and content analysis. This, in order to answer the following question:

How is the situated acquisition of English communicative competence favored by the perspective of learning community projects?

Moreover, internal coherence is embraced by establishing theoretically coherent relationships between concepts, in order to contribute to the body of theory already constructed by other authors. In the end, this is a key element of qualitative research (Krause, 1995).

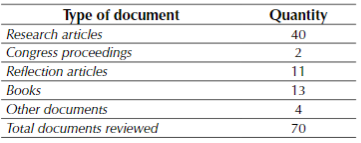

In this sense, some databases were consulted, such as Scopus, Scielo, EBSCO, Springer Journal, and Google Scholar. Throughout the first scan, it was possible to select 90 documents. Some of them were taken as the background to draw an overview of previous research on the subject. From these 90 documents, 70 were reviewed for this literature review. Table 1 provides a detailed view of the number of documents reviewed and the nature of each of them:

Firstly, a document review was carried out to find the documents, research articles, reflection articles, and papers that would draw the landscape of the topic, i.e., the state of the art. The categories that guided this search were: learning communities, communicative competence, and sociocultural characteristics. After that, some authors were selected as references in the subject matter, as several documents and research projects on the topic were written and developed by them. This, in association with the snowball technique, which means that an experienced author in the subject under study recommends other authors and references. Then, by following these tracks, a solid comprehension of the subject is reached. Consequently, said arguments, ideas, and proposals are contrasted. The authors enter into a symbolic dialogue, guided by our interpretations, which results in a new approach and the construction of knowledge about the subject under study.

Active participation and commitment: the first steps towards building communities in Antioquia, Colombia

Bedoya et al. (2018) carried out a research study whose main concern was the creation of a Community of Practice (hereinafter CP) through the integration of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) as a didactic tool in teaching practice. According to this study, Étienne Wenger was the one who proposed this term: “when observing the way in which scientific communities build and disseminate knowledge, he wanted to take this work methodology to the corporate field in order to facilitate and to dynamize the processes of construction and exchange of knowledge” (Wenger, cited in Bedoya et al., 2018, p. 123, self-translated). Nonetheless, other authors define CP as “a group of people who share a concern, a set of problems, or a common interest about a topic, and who deepen their knowledge and their expertise in this area through continuous interaction” (Wenger et al., cited in Bedoya et al., 2018, p. 123, self-translated). The matter of the shared interest and common need is, in turn, a characteristic of learning communities.

Likewise, the construction of a learning community is built upon the interaction and commitment of its members. This finds a point of convergence with that stated by Bedoya et al. (2018) when they asserted that “doing CP requires not only sharing an interest in specific know-ledge, but also the commitment of its members to actively participate in the proposed tasks and activities” (p. 136, self-translated). This responsibility and commitment imply that member participation is the mainstay in a CP. Now, taking this definition into the field of Learning Communities, commitment embraces family support and participation in children’s education processes. Regarding family support, it was found that,

(...) although accompaniment is not everything, it is a structural part that defines, in the boy or girl and the young person, the ways of socializing, learning, and interacting with their environment, facilitating appropriate conditions for obtaining learning that distinguishes you from your peers. (Flórez et al., 2017, p. 213, self-translated)

During the process of reflection that derives from any research exercise, the authors proposed combining the efforts made by the family and the school. Thus, it is affirmed that “the raison d’être that brings together both the family and the school in a common vertex (is) their children” (Flórez et al., 2017, p. 213, self-translated). Consequently, it is possible to infer that a family is an institution with huge influences on the school development of its children. The relationship between family and school is seen as facilitating the educational exercise of the two institutions. Accompaniment starts with simple questions, such as asking how the school day was, who a child’s friends are, as well as being attentive to subtle changes in personality, habits, style, and so forth. This is not only related to provide the student with the didactic resources needed to study (Villalobos et al., 2017).

What was previously proposed by Villalobos et al. (2017) is complemented with what Pérez and Londoño-Vásquez (2015) found about the relationship between family speech and practice, which often shows inconsistencies. In this sense, it is asserted that academic performance would be better if there were a correspondence between what the family says and what the family does. For example, a family member says that it is important to study because it is the best way to attain a better life quality, but then, when analyzing the case, one notices that there are no study habits proposed by that family or, in some cases, the family members do not even like studying, thus fostering a negative academic performance.

It is possible to say that, based on these research results, there is a recognition of families’ responsibility and commitment regarding the education of their children. Moreover, in the review of these research studies, iterative conceptual elements were found, concepts such as communication, open dialogue, dialectical action, and reciprocal relationship, which are substantial in the relationships that parents establish with their children. Besides, they have an incidence in the students’ motivation during the education process. Correspondingly, open dialogue is essential for enhancing the parents-children relationship. Indeed, listening to positive words and expressions is something that can boost student motivation towards learning (Villalobos et al., 2017). Similarly, in a research study conducted by Tilano et al. (2009), the perceptions of sons and daughters regarding communication and affection in their homes and the relationship of these factors with their academic performance were analyzed. It was found that

(...) those students with a low academic performance show lower affective and communication levels (Father = 32.67 - Mother = 38.14), and that students with a medium performance perceive a more communicative and affective family environment (Father = 34.83 - Mother = 40.01), but not higher than in those students with high academic performance (Father = 35.90 - Mother = 41.48) (...). (Tilano et al., 2009, p. 45, self-translated)

To summarize, at the local level, there has not been much interest in consolidating learning communities. Despite this, there is an interest in studying the different ways in which the social - and socializing - institution called family influences or affects the dynamics that occur in education institutions. This reflects the need to establish sustainable links and join forces between both institutions. More research is still needed about learning communities and the advantages of joint efforts between the school and the family, at least at a local level.

Education process and the influence of the students’ family

Espitia and Montes (2009) carried out a study in the Costa Azul neighborhood (Sincelejo, Colombia). Through this research, Espitia and Montes (2009) discovered that the number of children that make up a family has a direct impact on the resources and academic support strategies established by them to help children. The more children a family has, the more difficult it will be to have all the necessary resources. In addition, they found that teachers conceive school as something isolated from the community. They think that parents leave them alone with the education of their children and disregard all responsibility.

Additionally, Razeto-Pavez carried out a study in Chile, in which he discovered how social workers experience the process of home visits to students’ families. This author states that, even though there is already an interest in family participation in the students’ educational process, not much has been said about what strategies should be implemented to this effect. Therefore, he proposes home visits as one of the ways in which the family can be involved in the education process. The aforesaid strategy is understood as a means “to move towards the encounter between families and schools, with the intention of supporting student learning” (Razeto-Pavez, 2020, p. 4, self-translated). During this research, it was found that families are used to being visited, called, or considered only when something bad or negative happens regarding their child: either they did something improper or something bad happened to them (Razeto-Pavez, 2020). Furthermore, Razeto-Pavez (2020) asserts that the reasons or causes for contacting the family are all notably negative most of the time.

On the other hand, Muchuchuti (2015) inquires about the processes of parent participation in the education of their children, as well as their repercussions on academic performance. This research was carried out in the Matabeleland province, in the country of Zimbabwe. It was found that parents with children studying in public or rural schools are less interested in communicating with their children’s teachers and in understanding the school environment of their children than parents who have their children studying in private schools (Muchuchuti, 2015). Part of this gap between the private and the public and, even more, between the private and the rural public, has to do with access to resources and the family integration strategies established by schools (Muchuchuti, 2015). This failure on the part of public and rural education institutions to involve parents in the education process is also addressed by learning community projects; in this type of projects, the participation of all stakeholders is essential - it is uplifting. It is assumed, from the beginning of the project, that the degree of family involvement in the education process has a lot to do with the academic performance of the children (Soler et al., 2019; Rodríguez-Oramas et al., 2022).

Besides, García et al. (2015) classify family participation in a dichotomous way: deficit or standardized2. On the one hand, deficit is a concept used to group those families whose relations with the school and its demands are precarious or poor. On the other hand, there are standardized families that are contrary to the former, that is, their relationship with the school is one of proximity (García et al., 2015). This is the reason why learning community projects are based on dialogic learning and the participation of all members within the education community, with the aim to transform the center in which the project takes place and the environment where the institution is situated (López et al., 2020). Such a project implies moving from individual work to collective action, and the way to do that is joining forces between the family, the community, and the school (García-Cano et al., 2016).

A final aspect to mention about the findings of this research is that “the opportunity to link the diversity of voices within the institution causes a conception of teaching work associated with emerging knowledge and to the very scenario in which it occurs” (García-Cano et al., 2016, p. 262, self-translated). This leads to “joint decision-making leading to the co-management of the school institution” (García-Cano et al., 2016, p. 264, self-translated). One of the outputs of such an eminent proposal is the contextualization of the education act. It is worth adding that local knowledge acquires a special value with this proposal (Bolaños et al., 2018).

Learning communities around the world

All members of the education community can contribute to the teaching and learning process based on their capabilities and worldview. That is why joint work is what learning communities are intended to build. Hence, Acosta and Poveda studied a learning community of teachers in 2014. “In the case of this project, the cultural group studied is the teachers, who reflect ideas, practices, and conceptions of the world through reflections on the how and what for of English teaching” (Acosta & Poveda, 2014, p. 8). In addition, Álvarez and Fernández carried out a research study that takes intercultural competence and its components as the central axis. This study involved fourth-semester university students. Byram (cited in Álvarez & Fernández, 2019) proposes five dimensions that make up intercultural competence: “Attitudes, Knowledge, Skills (of Interpreting and Relating, of Discovery and Interaction), and Critical Cultural Awareness/Political Education” (p. 26).

Moreover, Jiménez (2012) carried out a study in a public school in Bogotá, Colombia. This research dealt with the representation of social identity in a virtual learning community on Facebook. Interactive activities allowed the participants (tenth graders) to play an active role within the community. This was indeed due to the several activities and strategies implemented during the study. Through this virtual learning community, students became “involved in most activities proposed, such as posts, comments, e-activities, chatting, pictures, and tags, among others. These types of activities allowed the EFL learners to become active participants inside the community” (Jiménez, 2012, p. 186).

One aspect to be highlighted about the findings of this research is that “students used ‘you’ to indicate other members’ identity, as well as of ‘we’ to recognize themselves as part of the community (Jiménez, 2012, p. 192). This we is precisely the one that is sought in a learning community, a we that leads to problematizing a situation and to seek solutions and ways of action within the community. Besides, the iterative concepts that appear when the author refers to learning community should not be overlooked, concepts such as become part of, sense of belonging, interaction, participation, communication, and dialogical interactions. All these concepts are interdependently related to building a learning community and asserting intercultural competence through the learning of the English language.

The components of intercultural competence are mentioned in this document, as this initiative to build a learning community has to do with the development of communicative competence. Learning and teaching another language imply a whole cultural baggage. This is to say, “besides reaching communicative competence, learners are expected to develop intercultural competence” (Álvarez & Fernández, 2019, p. 23). Two of the participants, mentioned only by the initials of their names in order to protect their identities, propose conclusions that go in this direction: “JQ and AG’s descriptions (...) indicate that language is deeply rooted to culture or, what is more, language is itself culture” (Álvarez & Fernández, 2019, p. 34). These proposals by JQ and AG are deeply related to what Agar (cited in Álvarez & Fernández, 2019) affirms when he says that “language fills the spaces between us with sound; culture forges the human connection through them. Culture is in language, and language is loaded with culture” (p. 34).

In this sense, language is fastened with culture and, consequently, with history which simultaneously leads to knowledge. The interrelationship that can be established between these components constitute human societies and endow them with consciousness regarding their action in the world. Accordingly, “aware that I can know socially and historically, I know that what I know cannot escape historical continuity” (Freire, 1997b, p. 19, self-translated). It is possible to say that human societies are bounded and, at the same time, emancipated to a certain degree by history and context. The latter is translated as the input of culture, and culture as its output. Thereupon, it is deduced that, to construct learning communities around English communicative competence, it would be necessary to consider society, language, family, culture, and history, given that they all condition the human being.

In addition, Montoya et al. (2015) proposed that “social interaction contributes to evolution and dynamism in learning communities” (p. 10, self-translated). Social interaction becomes participation when it involves the community. Participating in a learning community leads to building knowledge collectively, which agrees with Montoya et al. (2015) when they say that “in these already established communities, children, youths and adults participate; they are those who deepen intergenerational learning” (pp. 25-26, self-translated). The aforementioned intergenerational learning offers the opportunity to establish a dialogic relationship between generations, who contribute from their understanding of the world (Flecha, 2004; Rodríguez et al., 2020; Rodríguez-Oramas et al, 2020; Barros del Río et al., 2021). Likewise, learning communities are based on a “bottom-up” approach (Montoya et al., 2015; Buslón et al., 2020); this is how resistance to dominant “top-down” approaches is done, as the latter exclude the so-called peripheral contexts (Valencia, 2013; Correa et al., 2014).

Furthermore, learning communities are understood as “projects of social and cultural transformation of an education center and its environment, based on dialogic learning, with the purpose of linking the entire community to the education process in specific spaces, including the classroom” (Ferrada & Flecha, cited in Beltrán et al., p. 59, self-translated). According to the proposal made by Beltrán et al. (2015), learning communities provide a voice to students, teachers, parents, and other members of the community in which these types of social projects are implemented. The opinions of each member about education are the ones that enrich the educational process and endow it with community relevance by meeting the demands of the parties directly and indirectly affected by education; learning community projects entail inclusion (Girbés-Peco et al., 2019).

In the province of Jaén, Spain, Cantero and Pantoja (2016) carried out a study in seven education centers that were transformed into a learning community. The aim of this study was to find out how these transformation processes took place. When they inquired about the results of the consolidation of interactive groups, they discovered that “teachers think interactive groups are the ones that provide the greatest educational results, and it is the action they perform most frequently in their classroom” (Cantero & Pantoja, 2016, p. 737, self-translated). In this regard, it is concluded that “successful actions such as interactive groups, dialogic gatherings, etc. suppose an acceleration of learning and allow all students to get the most out of their skills” (Cantero & Pantoja, 2016, pp. 741-742, self-translated). Moreover, students’ learning processes are driven by the means of interaction and bonds they can establish with classmates. Therefore, interactive groups are conceived as successful educational actions (Valero et al., 2018; Zubiri-Esnaola et al., 2020).

When thinking about the implementation of learning communities, it is possible to find that, on the one hand, there are advantages for parents being interested in their children’s academic process (Renta et al., 2019; Serrano et al., 2019); and, on the other hand, there is great potential in parents being trained at the same establishment as their children. This allows them to give continuity to the activities that are done in the school (García et al., 2018). Accordingly, to build a learning community on solid foundations, there are two inexorable components: participation and co-responsibility (Castillo et al., 2017). One aspect that these authors highlight about learning communities is dialogue and horizontal participation. Here, the teachers are not the intellectuals, much less those who can do the most. Horizontal relationships and egalitarian dialogues (García et al., 2020; Roca et al., 2022) are typical of this type of projects.

Research shows that there are many advantages and enormous potential in building a learning community. This is because it seeks to involve the greatest number of stakeholders in the issue of education. Nonetheless, it cannot be assured that, just by transforming an education center into a learning community, it should already be taken for granted that it is innovative, or that the status quo has been changed to some extent. This, due to the fact that there is a principle of identity in learning communities, i.e., the construction principle, which is to say, a learning community is an unfinished project. It is not a result, but a process. It is not instantaneous; it is a process that takes place over time. Basically, all these research studies offer a broad horizon regarding the research projects that have been developed in Colombia which directly and indirectly have to do with the construction of learning communities. It can already be seen in this horizon that learning community projects are beginning to arrive in Latin America to offer answers to this complex society, which deserves contextualized, local solutions.

Discussion and analysis

Nowadays, society is characterized, among other things, by making use of dialogue as a means of expression. A wide variety of human groups and minorities have raised their voices. This has become a plurality of the social phenomenon that is opposed to any homogenization intended to be applied to it. This change in social dynamics is simply another example that the social world is not static and much less solid or immutable. On the contrary, the construction of the social world is possible thanks to history; it is composed of ever-changing phenomena (Freire, 1997b, Berman, 1998). In this sense, change destabilizes the old foundations. Adapting becomes a process, as well as a risk (Flecha & Puigvert, 2004). However, dialogue is presented as a motive for uncertainty and, simultaneously, as an enabler of intersubjective consensus (Vygotsky, 1995; Lantolf, 2000), which, when considering the plural nature of reality, provides some stability to the fleeting and elusive present. A constant present that Bauman (2002) describes as liquid. Considering the speed with which the social phenomenon changes, it is necessary to have tools, but this is not just about the material to guide a class; it is a kind of social material, better called the social component, i.e., the social body is the only means to advance at the pace of today’s society.

This broad perspective with regard to the development of learning communities and the arrival of this type of project in Latin America is essential to comprehending why this project is related to the development of the English communicative competence. When reviewing some articles (Levinson et al., 2009; Usma, 2009; García & García, 2012; Correa et al., 2014; Usma, 2015; Bonilla & Tejada-Sánchez, 2016; Peláez & Usma, 2017; Gómez, 2017; Usma & Peláez, 2017) derived from research studies, similar preoccupations emerged in the analysis of different authors. What all these authors have in common is the criticism they make of Latin American and Colombian programs in promoting the learning of English.

The question is: if it has been a while since this criticism was voiced, why do we still have the same problems that were pointed out in all of these documents, as well as others that are not included in this paper? Moreover, why look for answers in the same way it has always been done? Can someone find a different result by applying the same strategy and method? Why not change the traditional way of elaborating Language Education Policies (LEPs)? Solutions have been sought in theories or by asking some policy stakeholders such as Language Policy Makers - and, lately, teachers. As a consequence of these procedures, there are policies that prioritize the interests of certain entities - the so-called hidden agendas (Shohamy, 2006). The thing is, reducing stakeholders to only teachers is quite naïve, and even dangerous.

It was previously shown that parents can and need to be taken as stakeholders of education, as they are the complementary axis of the education process. Nonetheless, learning community projects are not limited to teachers, institutions, and parents; they actually seek to embrace all actors in community within the process. When reading Shohamy’s concerns regarding LEPs, it is evident that she calls for other educational actors to be included in “creation, introduction, and implementation” (2009, p. 49). Peláez and Usma (2017) would add the appropriation of such policies.

Now, the question is: why do learning community projects represent a possible solution regarding the problems that have been pointed out? McLuhan and Powers (1995) affirmed, in a really accurate way, that the society of the 21st century is set to become a global village due to the accelerated technological advance that interconnects us. Human societies are hurled into a reality of collective individuals and individual collectives; this is the pure duality in which we all live. As Morin (1999) asserts, “there is always culture in the cultures, but the culture does not exist except through the cultures” (p. 28, self-translated)3. This is why human individuals are never independent from the human social body. This is one of the strongest arguments to defend that learning community projects can be implemented to strengthen and improve the way in which LEPs have been elaborated and applied in Colombia.

Regarding the emerging categories, when reviewing for sociocultural characteristics, they were deeply rooted in several relationships, such as the family and the school, parent-teacher, teacher-parent, children-parent, and parent-children. Subsequently, it was found that horizontal relationships, family participation strategies, shared responsibility, and shared leadership are associated with learning community projects. Lastly, English communicative competence is linked to contextualized curriculum, context as content, and down-top approaches. These three macro categories are correlated to a subcategory: joint work.

This study was intended to consolidate and strengthen the link between learning community projects and the development of English communicative competence. Its most essential link lies in its methodological aspect, as both, taken from a sociocultural perspective, aim for the construction and contextualization of their education practices, be it learning or teaching. When education practices regarding the development of English communicative competence are contextualized, they are endowed with cultural relevance. Thus, sociocultural characteristics play an important role (Barriga, 2003). In summary, learning community projects are founded upon people’s needs rather than on government suppositions about them. That is why they are considered to be a successful action in the transformation of education.

Conclusion

To summarize, learning communities, more than a joint effort by stakeholders that meet to report on administrative aspects about education, are projects that grant all their members the right to participate and be heard in the construction of knowledge. Union is an essential element in learning communities, given that, without it, communication would not be possible; yet one must seek to go beyond mere union. One must seek to rely on dialogue, as, without dialogue, it would be impossible to refer to learning communities and the commonly known education communities. These communities help to keep parents on track about administrative aspects regarding their children’s learning process. However, they are misnamed as communities because families, parents, and students are only part of them to the extent of reporting, rather than authentically participating.

Considering that, through the development of English communicative competence, the construction of learning communities is being proposed, it is crucial to define how language will be considered. From this perspective, and trying to relate it to the conceptions of learning communities, language cannot be taken as a static, rigid, isolated item. On the contrary, in this case, language should be approached as a living being, which changes as society and culture change. Therefore, focusing on English learning and teaching practices only from linguistic components would not be enriching enough to have cultural relevance. It is essential to transcend from the traditional content to contextualized thematic units, from content review to knowledge appropriation. Instead of separately working on the verb to be, simple present tense, or conjunctions, to name a few, it is rather necessary to use English to address issues that affect communities, for example, violence, discrimination, and environmental care, among others. Basically, since English is a language like Spanish, Japanese, or any other, it can be taken as a means to construct a learning community focused on local problems.

Learning community projects are starting to gain importance in Latin America. These kinds of projects tally with the emerging southern methodologies that are being developed on this side of the American continent (De Sousa, 2018). Not only is it considered that the communities have knowledge and history, but they are also allowed to participate with their voice. Learning community projects are beginning to reach Latin America to offer answers to this complex society that demands contextualized, local solutions (Fals-Borda, 2004).

It is recognized that families and other parties interested in the education process can make their contributions.

From the beginning of the project, it is assumed that the degree of family participation in the education process has a lot to do with children’s academic performance. Furthermore, it is recognized that family-school communication can positively or negatively affect students’ education process. This proposal of learning communities is intended to build synergies between educational stakeholders in order to approach situated needs from a local perspective. However, by transforming an education center into a learning community, it cannot be assured that it is innovative or that the status quo has been changed to some extent. Everything depends on the intention of the people undertaking the project and the negotiation that may - or may not - occur between the members of the education community.

Finally, it has already been seen that learning community projects are not yet common in Colombia. Based on that, it is recommended to carry out some research on this matter from a Participatory Action Research approach. Another possible study could involve the transformation of an education center into a learning community, as is the case of some of the studies reviewed in this paper. It is necessary to take into consideration that learning community projects are flexible, and they always need to be adapted in terms of their context, purpose, people, situated problems, and so forth. In this sense, it is also possible to conduct a research study on a learning community composed of teachers, parents, students, or all of them together. This will always depend on the consensus reached by the participants. Additionally, some research is still to be done on virtual learning communities, rural learning communities, and even on comparisons between a learning community in a public school and that in a private one