Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Pensamiento Psicológico

Print version ISSN 1657-8961

Pensam. psicol. vol.14 no.1 Cali Jan./June 2016

https://doi.org/10.11144/Javerianacali.PPSI14-1.ebsv

Evaluation of a Brazilian School Violence Prevention Program (Violência Nota Zero)1

Evaluación de un programa brasileño de prevención de la violencia escolar (Violência Nota Zero)

Avaliação dum programa brasileiro de prevenção de violência escolar (Violência Nota Zero)

Ana Carina Stelko-Pereira2

Lucia Cavalcanti de Albuquerque Williams3

Universidade Estadual do Ceará, Ceará (Brasil)

Universidade Federal de São Carlos, São Carlos (Brasil)

1This paper is part of the the first author's Ph.D. dissertation at Universidade Federal de São Carlos, Brazil, which received the grant # 2008/10681-7 from The São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP). The authors of this paper are responsible for the opinion; hypotheses, conclusions and recommendations presented on this article and those do not necessarily express FAPESP's opinion

2Ph.D., Silas Munguba, 1700, Universidade Estadual do Ceará, Bloco P, Coordenação de Psicologia, Fortaleza, Ceará, Brasil. ZIP: 60740-000, 55 85 98122 1984. Email: anastelko@gmail.com

3Ph.D

Recibido: 27/02/2015 Aceptado: 30/10/2015

To cite this article / para citar este artículo / para citar este artigo

Stelko-Pereira, A. C. & Williams, L. C. A. (2016). Evaluation of a Brazilian School Violence Prevention Program (Violência Nota Zero). Pensamiento Psicológico, 14(1), 63-76. doi:10.11144/Javerianacali.PPSI14-1.ebsv

Abstract

Objective. This study assessed the implementation of a program to decrease the levels of school violence, maximize student engagement, and improve teachers' well-being. Method. In total, 71 students (21 from the intervention school and 50 from the control group school); 13 educators (8 from the intervention school and 7 from the control group school) answered the study instruments. Both public schools were located in a highly vulnerable area in Brazil. The following measures prior and post intervention were collected: School Violence Scale; School Engagement Scale (students) and Goldberg's General Health Questionnaire; School Violence Scale (teachers). Follow-up measures were taken with the intervention school after eight months. The Program consisted of twelve 90-minute sessions to educators on school violence prevention, involving presentations, discussions and classroom exercises. Results. Significant reductions in self-reported perpetration of violence by students (M pre-intervention = 15, M post-intervention = 13, z = -2.5, p = 0.01), and of teachers' mental health problems (Mdn pre-intervention = 1.8, Mdn post-intervention = 1.4, z = 2.1, p = 0.03) were noticed in the experimental group after the intervention, in comparison to the control school. However, the program did not improve school engagement, nor did it diminish student victimization by staff or teacher victimization by students. Lower levels of peer-to-peer violence, as reported by students were maintained in the follow-up assessments. Conclusion. Despite the limitations of the study, such as a small sample, the existence of pertinent (although limited) results is encouraging, as there are not many similar initiatives in developing countries.

Keywords: School, violence, bullying, program evaluation.

Resumen

Objetivo. Este estudio evaluó la implementación de un programa para disminuir los niveles de violencia escolar, maximizar la participación de los estudiantes y mejorar el bienestar de maestros. Método. Participaron 71 estudiantes (21 de la escuela de intervención y 50 controles) y 13 educadores (8 de la escuela de intervención y 7 del control) de dos escuelas públicas de una zona de alta vulnerabilidad en Brasil. Antes y después de la intervención se aplicaron a Escala de Violencia Escolar, Escala de Adherencia Escolar (estudiantes) Cuestionario General de Salud de Goldberg, Escala de Violencia Escolar (maestros). 8 meses después de finalizada la intervención se aplicaron nuevamente los anteriores instrumentos, solo en la escuela de intervención. El programa consistió de 12 sesiones de presentaciones, discusiones y ejercicios de 90 minutos para los educadores en la prevención de la violencia escolar. Resultados. Se encontró una disminución significativa en autoreporte de la perpetración de la violencia de los estudiantes (M pre-intervención = 15, M pos-intervención = 13, z = -2.5, p = 0.01) y de los problemas de salud mental de los maestros (Mdn pre-intervención = 1.8, Mdn pos-intervención = 1.4, z = 2.1, p = 0.03) en comparación con la escuela control. Sin embargo, el programa no mejoró la participación escolar ni tampoco se produjo una disminución de la victimización de estudiantes por los docentes o una reducción de la victimización del profesor por los estudiantes. Los niveles más bajos de violencia entre los estudiantes, según lo informado por ellos, se mantuvieron en las evaluaciones de seguimiento. Conclusión. A pesar de las limitaciones del estudio como el tamaño muestral y el impacto de los resultados, los hallazgos de esta investigación resultan alentadores si se tiene en cuenta que existen muchas iniciativas similares en los países que se encuentran en vía de desarrollo.

Palabras clave: Violencia, escuela, intimidación, evaluación de programas.

Resumo

Escopo. Este estudo avaliou a implementação de um programa para diminuir os níveis de violência escolar, maximizar a participação dos estudantes e melhorar o bem-estar de professores. Metodologia. Participaram 71 estudantes (21 da escola de intervenção e 50 controles) e 13 educadores (8 da escola de intervenção e 7 de controle) de duas escolas públicas de uma zona de alta vulnerabilidade no Brasil. Antes e depois da intervenção foram aplicadas a Escala de Violência Escolar, Escala de Aderência Escolar (estudantes), Questionário Geral de Saúde de Goldberg, Escala de Violência Escolar (professores). Oito dias depois de finalizada a intervenção foram aplicadas novamente só na escola de intervenção. O programa consistiu em doze sessões de apresentações, discussões e exercícios de 90 minutos para os educadores na prevenção da violência escolar. Resultados. Foi achada uma diminuição significativa em auto-reporte da perpetração da violência dos estudantes (M pré-intervenção = 15, M post- intervenção = 13, z = -2.5, p = 0.01) e dos problemas de saúde mental dos professores (Mdn pré- intervenção = 1.8, Mdn post- intervenção = 1.4, z = 2.1, p = 0.03) em comparação com a escola controle. Porém, o programa não melhorou a participação escolar nem produziu uma diminuição da vitimização de estudantes pelos docentes ou uma redução da vitimização do professor pelos estudantes. Os níveis mais baixos de violência entre os estudantes, segundo o informado por eles, foram mantidos nas avaliações de seguimento. Conclusão. Apesar das limitações do estudo como o tamanho da amostra e o impacto dos resultados, os achados desta pesquisa resultam alentadores se considerarmos que existem muitas iniciativas similares nos países em desenvolvimento.

Palavras chave: Violência, escola, intimidação, avaliação de programas.

Introduction

School violence is an international problem involving aggressive incidents of physical, psychological and sexual nature, as well as property destruction in schools, its surroundings or during school related events (Stelko-Pereira & Williams, 2013a). Students, school staff or parents may be involved in these violent incidents, (which may be single or repetitive violent acts), as victims, offenders, witnesses or in victim-offender roles. Bullying, a special category of school violence, is characterized by intentional and repetitive aggressive behaviors of an individual who is more powerful than the victim (Olweus, 2013).

The present study will describe a program to decrease school violence, covering both teacher and student victimization, as well as peer-to-peer aggression, such as in bullying. The literature has controversies with the definition of the terms school violence and bullying, but such discussion exceeds the goal of the present study (See Finkelhor, Turner, & Hamby, 2012; Williams & Stelko-Pereira, 2013a for some of this debate).

Several countries, including Brazil, have made efforts to prevent school violence due to its significant negative impact. The harsh consequences of school violence have been studied more often focusing on students rather than school employees (Espelage et al., 2013), and there has been more research on the impact of bullying involving situations of potential violence among students, whereas staff impact has not been analyzed in detail.

The impact of school violence may be characterized into consequences for students, and for staff. The most serious impact of bullying and other types of school victimization for students usually involve depression, suicide ideation and attempt, substance abuse, psychosomatic symptoms, low school engagement, poor academic performance and school dropout (Due et al., 2005; Fleming & Jacobsen, 2010; Gini & Pozzoli, 2009; Hawker & Boulton, 2000; Kumpulainen et al., 1998). The negative impact on educators involves an increase in stress levels, poor overall health and increased absenteeism (Espelage et al., 2013).

In addition to studying the impact of school violence, many studies identify risk factors associated with the school environment, which may be altered by training teachers and school counselors. In a literature review, Hong and Espelage (2012) described some of the risk factors for school victimization: poor sense of school connectedness due to little emotional involvement among individuals in the school; irrelevance of the school context for the student, with few activities related to his or her daily life; teachers' low credibility when it comes to protecting students and tackling violent situations in school, among other variables.

Studies have stressed that school employees have not been acting effectively against school violence in Brazil (Stelko-Pereira, Albuquerque, & Williams, 2012), as in other countries (Smith & Shu, 2000). In this regard, Strohmeir and Noam (2012) suggested it is crucial that educators learn to: (a) properly detect bullying in schools, since many do not consider indirect violent situations, such as exclusion and spreading rumors, as bullying. (Educators often minimize instances of non-physical violence and underestimate the number of students involved in violent episodes); (b) differentiate more severe cases from less severe ones, since educators do not always notice the importance of repeated victimization of a student in denoting the occurrence of bullying; and (c) intervene differently when dealing with perpetrators, victims and bullying witnesses, as educators, in general, only comfort the victim after the occurrence of the violent situation, rather than properly preventing or stopping the victimization.

Another important reason to involve educators in the prevention and intervention to address school violence refers to what Alsaker and Valkanover (2012) discuss in relation to bullying: "(...) even if an outside expert could help stop an actual bullying problem in a class, bullying problems may come back in the same class or appear in another class some years later" (p. 17). Therefore, it is vital for educators to learn strategies to face and prevent bullying and other types of school violence problems. These same authors argued that educators in general have little support from colleagues for dealing with bullying, and we believe this may be generalized to other school violence situations. Alsaker and Valkanover argued that group sessions with educators in prevention programs are essential in order to develop the habit of cooperation among themselves in such situations.

Roland and Midthassel (2012) point out how essential it is that teachers have control of students' behaviors in the classroom. Poor leadership from the teacher facilitates students behaving violently towards their peers, and even towards the teacher himself. The authors emphasized that educators must be authoritative, that is, they should impose rules clearly and consistently, whereas at the same time being supportive and responsive to the needs and interests of students. Additionally, it is important that teachers analyze the power dynamics occurring among students, and consequently direct student leadership skills in a positive way.

Another factor that contributes to school victimization relates to poor performance of the employees in relation to any suspicion of child abuse. Given that victimization and/or perpetration of violence at school and a history of child maltreatment are related (Lev-Wiesel & Sternberg, 2012; Pinheiro & Williams, 2009), it is important to address both problems together.

A meta-analysis of prevention programs to reduce bullying (Ttofi & Farrington, 2011), showed that working with teachers to achieve greater supervision in the schoolyard, applying rules firmly, promoting cooperation in school and, improving classroom discipline management, reduces victimization and perpetration of violence by students by about 20%. According to a more comprehensive meta-analysis on school violence, bullying and corporal punishment in schools (Blaya, Debarbieux, & Denechau, 2008), it is believed that the above strategies are also valid to prevent and/or reduce the occurrence of possible violence among students, and among students and educators.

Despite this meta-analysis, it is unclear whether such strategies would be effective in countries where socio-economic conditions are worse, since the studies investigated in such systematic reviews were mostly conducted in the United States, England and Norway. Baker-Henningham, Scott, Jones and Walker (2012) discuss that in countries with low or medium socioeconomic levels, resources are fewer and the problems are greater, thus such strategies may not be appropriate or effective. In this respect, Baker-Henningham et al. (2012) were pioneers in applying the Incredible Years: Teacher Training Program (Webster-Stratton, 2000) developed for the North America and Jamaica. Prior to implementing the program, the authors made adjustments to the teaching materials to present situations related to the school context of those countries, increasing the amount of meetings, enhancing the importance of positive reinforcement of students' skillful behaviors and pro-active action in classroom management. The effects of the intervention in Jamaica were positive and more significant than those obtained in the country of origin, especially considering that the Jamaican teachers had lower academic training, and that, prior to the intervention, students' levels of aggression were higher than in the United States.

Adapting and evaluating programs originally created in developed countries may assuredly be an effective strategy for emergent nations. Nevertheless, investigations that develop and evaluate original programs in more vulnerable countries are also relevant, since such programs may be more appropriate for those nations or suggest other alternatives for prevention. Thus, the aim of the present study was to assess the impact of the Brazilian Program Violência Nota Zero with regard to decreasing the levels of school violence by decreasing bullying, maximizing student engagement, as well as improving teachers well-being and reducing student violence against them.

Method

Participants

The study occurred in two highly vulnerable Brazilian public schools situated in a mid-size São Paulo State city. These schools were located six blocks from each other, with an enrollment in each school of about 600 students in grades 6th to 9th, and 45 teachers and three counselors. Both schools were rated at the worst possible value level in the Social Vulnerability Index of the region where they were located (equal to six over six ). This index refers to regions with low socioeconomic status, large concentration of young families, and low levels of income and education.

One school was randomly chosen to receive the intervention first (School A), and later (School B). In School A, 41 educators signed Informed Consent Forms and were present at the program activities. In School B only 15 teachers signed Informed Consent Forms. Approximately, 900 students answered the instruments at the beginning of the study (500 from School A and 400 from School B), representing approximately 50% of the student body for each school.

Only students and staff who answered the instruments in all phases of the study (pre and post interventions and follow-up) were considered participants in School A. I n terms of the control group, in School B, only students and staff who answered all the instruments during pre-interventions 1 and 2 were included as participants. Thus, a total of 15 educators and 71 students from grades 6th to 9th took part of the final study, representing only eight educators (seven teachers and one school counselor), and 21 students from School A, and seven educators (six teachers and one counselor), and 50 students from School B.

Instruments

The staff of both schools answered the following scales.

The School Violence Scale - Revised Teacher Version.

Developed by Stelko-Pereira & Williams (2013a), is composed of the following sub-scales, obtained through factor analysis (Stelko-Pereira, 2012): (a) frequency of victimization of employees by students (a = 0.85); (b) severity of victimization of employees by students (a = 0.78); (c) knowledge of victimization of students by students (a = 0.96); and (d) risk behaviors of students (such as substance abuse, bearing of weapons, a = 0.89).

Goldberg's General Health Questionnaire (GHQ).

This questionnaire was developed by Goldberg (1972), and translated for the Brazilian population by Giglio (1976). It was subsequently validated for the Brazilian population by Pasqualli, Gouveia, Andriola, Miranda and Ramos (1996). It consists of 60 items involving four-alternative answers, which assess psychiatric non-psychotic symptoms. The instrument demonstrated excellent internal consistency index (a = 0.95).

On the other hand, students responded to the following instruments.

School Engagement Scale.

Developed in the Netherlands this scale was initially designed to evaluate engagement by employees in the work context, and was subsequently shortened by Schaufeli, Bakker and Salanova (2006), and adapted for Brazil by Gouveia (2009) to assess student engagement in school. The Brazilian version of the instrument has 17 items answered on a seven-point scale, with the extremes 0 = Never and 6 = Always, and an internal consistency index equal to 0.89.

School Violence Scale - Revised Student Version.

This tool identifies incidents of school violence according to students, in a five-point Likert scale, with questions involving four subscales (Stelko-Pereira, Williams, & Freitas, 2010). One subscale refers to the victimization of students by other students, with indicators associated with: (a) the frequency of events involving three dimensions physical violence (four items, a = 0.78); psychological violence (two items, a = 0.63); and property violence (two items, a = 0.64); and (b) the severity of the episodes involving the factors physical (three 3 items, a = 0.80); and psychological (four items, a = 0.70). Another subscale involves the victimization of students by school employees, presenting two factors: interpersonal victimization (four items, a = 0.72), and property damage (two items, a = 0.71). The third subscale assesses the perpetration of violence to other students, with three dimensions: perpetration of physical violence (six items, a = 0.83); non-physical violence (five items, a = 0.71) and cyber-violence (two items, a = 0.5). The last subscale investigates risk behaviors of students with a single factor (five items, a = 0.81).

Procedure

After Institutional Review Board approval, the study's aims and procedures were presented to the São Paulo State Board of Education, which, upon approval, indicated two schools located in a socially vulnerable region that would benefit from the program. An invitation was then extended to the participating schools, explaining the study goals and participation requirement. A school was randomly chosen to receive the intervention first (School A), and School B became the control school. Participating teachers, students and their parents provided signed informed consent. For ethical reasons, the intervention was also conducted in School B after its completion in school A (School B's intervention data will not be part of the present study).

The Violência Nota Zero4 intervention program is a Brazilian design to prevent violence and bullying in schools (Williams & Stelko-Pereira, 2013b). The program consists of primarily 12 weekly meetings of 90 minutes with teachers and school counselors, to help educators use behaviors and activities that promote the reduction of violent student-student and staff-student behaviors (and vice-versa). Although the program motivates educators to change the way they act towards students it does not involve students as participants.

The program aims to address the following school violence risk factors: (a) students may suffer child abuse (most likely at home), and school staff may not take the required or legal steps to protect them (Granville-Garcia, Souza, Menezes, Barbosa, & Cavalcanti, 2009; Pinheiro & Williams, 2009); (b) teachers do not identify school violent situations and its impact on students (Khoury-Kassabri, Benbenishty, Astor, & Zeira, 2004); (c) members of the school staff are felt by students to be unfair and untrusting (Reid, Peterson, Hughey, & Garcia-Reid, 2006; Schreck, Miller, & Gibson, 2003); (d) there are few recreational activities in the curriculum to facilitate student engagement and learning; (e) rules are not consistently and effectively applied in school (Reid et al., 2006; Schreck et al., 2003); (f) there are few positive consequences to students that behave well (Welsh, 2003); (g) some educators believe that scolding students, and suspensions are effective strategies to cope with inadequate student behavior (Blaya et al., 2008); and (h) there is a general belief that teachers cannot make a difference when it comes to diminishing school violence.

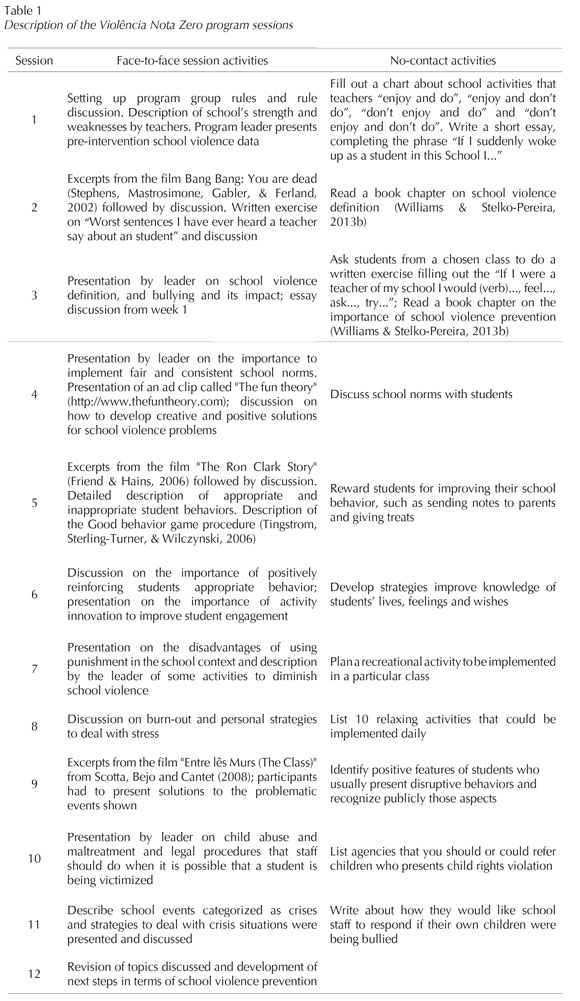

The protective factors that the program aims to address are: (a) better communication between school staff and Child Protection Agencies when there is suspicion of child abuse; (b) more strategies from teachers to listen to students' opinions and to the possible difficulties they may experience at home; (c) more student supervision by school staff (Welsh, 2003); (d) development of clear and fair school rules (Reid et al., 2006; Schreck et al., 2003); (e) more knowledge from staff on how to handle student aggression (Blaya et al., 2008); (f) teachers motivated to create new teaching strategies and adequate classroom management (Blaya et al., 2008); (g) more recreational activities for students; (h) positive consequences for students who behave well; and (j) teachers accept the possibility that they can intervene to reduce school violence, and develop plans in such direction. These risk and protective factors were chosen according to the author's professional experiences, as well as recommendations from the literature (Blaya et al., 2008). Details of the Violência Nota Zero program are described in Williams and Stelko-Pereira (2013b). Table 1 has a summary of the activities and topics for each session.

Teachers from both schools were invited to participate in the program at their School Team meetings. A certificate given by the State Board of Education was offered to participants who completed the program. The certificate was counted as continuing education credits needed for career enhancement.

In addition to face-to-face meetings, participants were individually required to do activities during the week, involving teachers reading materials, in addition to doing exercises and classroom activities with students. Face-to-face meetings were led by the first author (Program leader) with the help of an undergraduate Psychology student as assistant. Oral presentations by the Program leader involved multimedia and power-point resources, such as slides associated with the contents shown in Table 1 (i.e. how to develop effective rules for class participation; reasons to positively reinforce student's behavior).

The following steps were conducted in School A: pre-program evaluation, intervention, post-program evaluation and follow-up after eight months. For School B: pre-program evaluation twice, at the beginning of the study, and after School A completed the intervention.

Statistical Analyses

Intra or inter-school analysis of answers provided by students and staff, at different times during the study, occurred by using non-parametric tests using SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 19.0), as: (a) the analysis of symmetry and kurtosis values indicated that distribution of scores were asymmetric and not mesokurtic; and (b) Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk normality verification tests were conducted showing that the score distribution was different from the normal curve. The Wilcoxon test with repeated measures was used when comparing the same group of subjects regarding the measures before and after the intervention.

Results

Student and teacher samples from each school were initially compared regarding socio-demographic characteristics. No significant differences in terms of student age among respondents from the two schools were found (Mann-Whitney test, z = -0.31, p = 0.75), as the median age was 13 for both schools. In terms of student gender, 25% of the respondents were males in School A, while School B had approximately double proportion of boys (51%; X2 [1, N = 71] = 3.94, p = 0.04). With regard to the educator sample, no statistically significant differences were noted between schools in terms of gender (X2 [1, 15] = 0.74, p = 0.38). In School A, all eight teacher participants were females, whereas in School B five were females and two were males. There were no differences between the schools regarding teacher's age (z = -0.21, p = 0.8). In School A, the median age was 35, and in School B it was 37.5. In addition, there was no difference in relation to how long educators had been working in the profession (z = -0.08, p = 0.93). The median number of years in School A was 10 years, and 11 years for School B. Number of work hours was also equivalent in both schools with 36 hours in average per week (z = 0.36, p = 0.7).

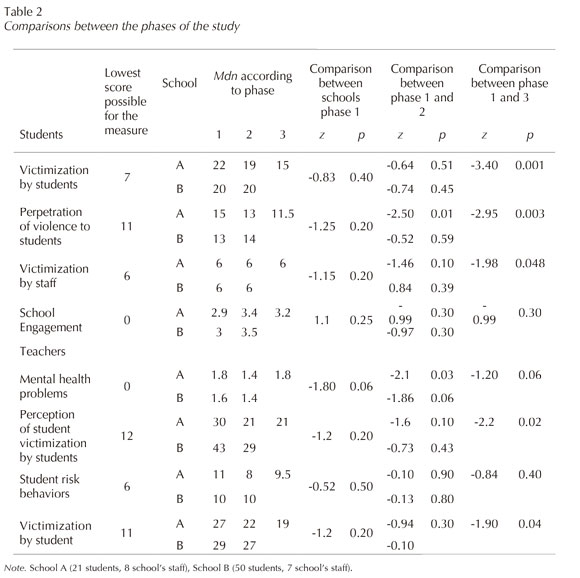

Mann-Whitney tests were conducted to compare both schools in the initial evaluation in terms of the main variables measured; no significant differences were found in terms of total student victimization by other students according to students and to staff; perpetration of violence by students according to students; teacher victimization by students; risk behaviors, and employees and school engagement. Table 2 presents comparison data between control and the experimental school for student and teacher scores on instruments from the study's Phase 1 (prior to the intervention in both schools); comparisons between scores in Phase 2 (postintervention for School A, prior to the intervention at School B), and Phase 3 contains comparisons between scores from Phases 1 and 3 (follow-up) for School A only. The Wilcoxon test for repeated measures was used to make such comparisons.

As seen in table 2, students from School A reported significantly less perpetration of violence towards other students, than those from the comparison School (B), after the program. This result was maintained after eight months in the follow-up. The median score of self-reported perpetration of violence to other students in post-program phase after the program was 13 and at follow-up 11.5; this difference was not significant, using the repeated measures Wilcoxon test (z = -1.5, p = 0.11).

A significant difference in terms of improving employee mental health scores regarding the preprogram (mdn = 1.8) and post-program median (1.4) scores in School A was also noted (z = 2.1, p = 0.03), and this did not occur in School B (mdn in phase 1 = 1.6 and in phase 2 = 1.4, z = -1.86, p = 0.06). However, the result obtained in School A with the program was not maintained after eight months, as Wilcoxon test with repeated measures showed (z = -1.2, p = 0.06).

Student risk behaviors, according to students, occurred at a too low of a frequency to perform statistical tests. During the pre-program phase, one student declared that he had smoked or consumed alcohol at School A, and this same student continued to declare that he had presented such behavior after the program. In School B, a student said he smoked at the school in the pre-program phase, and in the second evaluation two students declared smoking at the school; in addition, one student declared he had carried a knife to school for self-protection or to threaten other students, and this serious behavior was not present in the second phase (without the program).

Nevertheless, in terms of victimization by students and victimization by staff according to students, school engagement, teachers' perception of student victimization by other students, and staff victimization by students, there were no significant differences between pre-program and post-program comparing both schools.

During follow-up, in addition to less perpetration of violence towards other students by students, other variables showed positive changes, as presented in table 2, when comparing the median with the pre-program results. There were significant changes in relation to: (a) victimization among students according to students and staff; (b) victimization of students by staff; and (c) victimization of staff by students.

Discussion

The present study aimed to assess the impact of a Brazilian school violence program (Violência Nota Zero), with regard to decreasing the levels of school violence, maximizing student engagement, and improving teacher well-being. School's A and B violence scores were high before intervention, confirming the Board of Education's impression, and in accordance with the literature review on the relationship between high school violence levels and the degree of vulnerability from the school's neighborhood (Singh & Ghandour, 2012; Stelko-Pereira & Williams, 2013a).

The experimental and control groups were similar on most variables measured before the intervention (such student and teacher age, teacher gender, time that teachers had been working in the profession, and scores of violence), with exception of student gender. There were significantly more girls answering the measures in School A than B. In spite of the fact that the literature points out that boys are more aggressive, and also more victimized at school than girls (Artz & Riecken, 1997; Khoury-Kassabri et al., 2004; Warner, Weist, & Krulak 1999; Welsh, 2003), therefore raising the expectation that School B would present higher school violence scores than school B before the intervention, this was not the case in the present study.

Although no changes in student engagement were observed, significant reductions of self-reported perpetration of violence by students and improvement of teachers' mental health problems were noticed after the intervention, in comparison to the control school. The student positive changes achieved through this program are in line with what the literature states about the possibility of changing their behavior by changing the behavior of educators through specific training, that addresses school violence prevention, classroom management and fostering student-teacher bonding (Blaya et al., 2008; Hong & Espelage, 2012; Roland & Midthassel, 2012; Smith & Shu, 2000; Strohmeir & Noam, 2012; Ttofi & Farrington, 2011).

Furthermore, the results are in accordance with the literature with respect to the positive relationship among teachers' mental health and school violence scores (Gómez-Restrepo et al., 2010; Stelko-Pereira & Williams, 2012). When educators share their difficulties in facing school violence with other educators and with the program leader, the levels of teacher stress may be reduced (Domínguez, López-Castedo, & Pino, 2009; Sela-Shayovitz, 2009).

In spite of these positive results, the program did not have a significant impact in terms of pre and postprogram comparison in regards to the following variables: (a) according to students, victimization by students, victimization by staff, and school engagement; and (b) according to staff, teachers' perception of student victimization by other students, and staff victimization by students. Thus, the reduction on school violence while working exclusively with teachers, as pointed by Ttofi and Farrington (2011) was not possible to achieve. The following hypothesis may help to understand these negative results. First, methodological problems associated with the study's small sample; second, the fact that the program was not sufficient in terms of scope and duration considering the high entry level of violence observed in these schools. Third, violence among peers is associated with multiple risk factors from various systems, such as the family, the school, the community and the relationship among such systems (Hong & Espelage, 2012). Consequently, program reviews have shown that programs with multiple components tend to achieve better results. However, a wider scope for the program usually requires more human and material resources and more time and effort from participants, available in developing nations. Despite these difficulties, Williams and Stelko-Pereira (2013b) have detailed some possibilities of parent and student interventions to be incorporated into the Violência Nota Zero Program, such as using a simple folder with students (Stelko-Pereira & Williams, 2013b), as a teacher strategy to inform and discuss bullying.

Even if the program did not achieve all the changes measured at postintervention, surprisingly, eight months after the program ended, there were significant changes in relation to: (a) less victimization among students according to students and staff; (b) less victimization of students by staff; and (c) less victimization of staff by students; and (d) the positive results in respect of student's perpetration of violence were maintained. Unfortunately, the research design used in the present study does not allow us to conclude that the follow-up changes resulted from the educators' efforts to continue with program implementation. Although the lack of follow-up measures with the comparison school prevents us from being conclusive.

Nevertheless, the reduction of perceived victimization of students by staff after eight months of the program is consonant with the diminishing of staff's mental health problems at postprogram evaluation, and self-report perpetration of violence by students. Stelko-Pereira et al. (2012) noted that students who suffer physical violence from teachers in Brazil are also the students who practice more violent acts against their peers.

Qualitative data described in more detail in Stelko-Pereira (2012) indicated that staff affirmed that students changed their behavior and felt relief while discussing with the school community, school violence, and strategies to deal with this problem. Additionally, teachers recognized the program as being relevant, supporting its maintenance, and suggesting it should be enlarged to incorporate parents, Child Protection Agencies and the community in general.

This study does present several methodological limitations, the most serious one being the small number of participants. The low attrition rate was possibly due to the following reasons: (a) some students and staff were absent when the questionnaires were applied. Teacher absenteeism is high, in Brazil: about 20%, according to Gesqui (2014). (Teacher's salaries are not competitive, as according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD, 2014), Brazil is the last but one of 34 countries in respect of teachers' salary. In addition, Brazilian educators often have more than one job to increase their income, with high prevalence of stress and burnout (Codo, 2006). In terms of students, those who live in highly vulnerable areas often miss classes, one of the motives being only one in four students complete the mandatory eight years of education in this country (United Nations Development Program - UNDP, 2013); (b) many students and staff complained that they were tired of answering the questionnaires which took approximately 40 minutes for completion. In relation to their lack of motivation, Brazilian Institutional Review Boards regulations forbid giving financial incentives for research participation; and (c) unfortunately, unknown to the present researchers, a third school was opened in the neighborhood, resulting in a large number of students transferring during the study.

Although tailoring the program to two highly vulnerable schools in Brazil seemed to be advantageous, the small sample size hinders generalizability, and calls for the present study's replication before wide implementation of the Violência Nota Zero program. The great challenges faced by researchers in terms of high teacher and student absenteeism, limited interest in research participation, and transference of students to another school during the study are perhaps the reasons why there are not many published school violence assessment programs in developing countries.

Another limitation of the study is the lack of generalizability to Brazilian's schools not located in highly vulnerable areas. Nevertheless, the choice for schools in a violent and poor community is perhaps one of the study's strengths, particularly because some positive results were found, bringing some reason to be optimistic about larger and systematic changes. Future studies could replicate the present one with larger samples, and perhaps more robust results would be shown. Other suggestions involve the use of observational measures from student behaviors, in addition to using exclusively self-report measures, and controlling the intervention for gender differences.

The initial assessment unveiled very concerning school violence levels in both schools according to the students, showing that efforts to curb and prevail such phenomenon should be a priority. Despite the present study's limitations, the existence of pertinent - although limited results - is encouraging, especially given the serious nature of the initial violence problem, and the relative short duration of the intervention. In addition, Violência Nota Zero is one of the few violence prevention programs available from a developing country, and this is particularly relevant as Baker-Henningham et al. (2012) mention that cultural translation for programs may not respect the cultural characteristics of the population and available resources.

Pie de página

4Violence F Minus" would be a loose translation.

References

Alsaker, F. D., & Valkanover, S. (2012). The Bernese program against victimization in kindergarten and elementary school. New Directions of Youth Development, 133, 15-28. doi: 10.1002/yd.20004 [ Links ]

Artz, S., & Riecken, T. (1997). What, so what, then what? The gender gap in school-based violence and its implication for child and youth care practice. Child and Youth Care Forum, 26(4), 291-303. doi: 10.1007/BF02589421 [ Links ]

Baker-Henningham, H., Scott, S., Jones, K., & Walker, S. (2012). Reducing child conduct problems and promoting social skills in a middle-income country: Cluster randomized controlled trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 201(2), 101-108. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.096834 [ Links ]

Blaya, C., Debarbieux, E., & Denechau, B. (2008). A systemic review of interventions to prevent corporal punishment, sexual violence and bullying in schools. New York, NY: Plan International. [ Links ]

Codo, W. (2006). Educação: carinho e trabalho [Education: Affection and work]. Petrópolis: Vozes. [ Links ]

Domínguez, A. J., López-Castedo, A., &, Pino, J. M. (2009). School violence: Evaluation and proposal of teaching staff. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 109(2), 401-406. doi: 10.2466/pms.109.2.401-406 [ Links ]

Due, P., Holstein, B. E., Lynch, J., Diderichsen, F., Gabhain, S. N., Scheidt, P., & Currie, C. (2005). Bullying and symptoms among school-aged children: International comparative cross sectional study in 28 countries. European Journal of Public Health, 15(2), 128-132. doi:10.1093/eurpub/cki105 [ Links ]

Espelage, D., Anderman, E. M., Brown, V. E., Jones, A., Lane, K. L., McMahon, S. D., Reynolds, C. R. (2013). Understanding and preventing violence directed against teachers: Recommendations for a national research, practice and policy agenda. American Psychologist, 68(2), 75-87. doi: 10.1037/a0031307 [ Links ]

Finkelhor, D., Turner, H. A., & Hamby, S. (2012). Let's prevent peer victimization, not just bullying. Child Abuse and Neglect, 36(4), 271-274. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.12.001 [ Links ]

Fleming, L. C., & Jacobsen, K. H. (2010). Bullying among middle-school students in low and middle income countries. Health Promotion International, 25(1), 73-84. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dap046 [ Links ]

Friend, B. (Producer), & Hains, R. (Director). (2006). The Ron Clark Story [Motion picture]. EUA: California Home Vídeo. [ Links ]

Giglio, J. S. (1976). Bem-estar emocional em universitários: Um estudo preliminar [Emotional well-being in university students: A preliminary study] (Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation). Retrieved from http://www.bibliotecadigitalunicamp.br/document/unicamp.br/document/?code=000052814 [ Links ]

Gini, G., & Pozzoli, T. (2009). Association between bullying and psychosomatic problems: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 123, 1059-1065. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1215 [ Links ]

Gesqui, L. G. (2014). Absenteísmo docente na escola pública paulista: usos e abusos no amparo legal [The absenteeism of public school teachers: Use and abuse of legal protection]. Comunicações, 21(2), 33-40, doi: 10.15600/2238-121X/comunicacoes.v21n2p33-40 [ Links ]

Goldberg, D. P. (1972). The detection of psychiatric illness by questionnaire: A technique for the identification and assessment of non-psychotic psychiatric illness. London, Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Gómez-Restrepo, C., Padilla, A., Rodríguez, V., Guzmán, J., Mjía, G. Avella-Garcia, C. B. y Edery, E. G. (2010). Influencia de la violencia en el medio escolar y en sus docentes: Estudio en una localidad de Bogotá, Colombia [Violence influence in the school environment and in teachers: A study in a Bogota community, Colombia]. Revista Colombiana de Psiquiatría, 39(1), 22-44. Retrieved from http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext & pid=S003474502010000100004 & lng=en & tlng=es. [ Links ]

Gouveia, R. S. V. (2009). Engajamento escolar e depressão: um estudo correlacional com crianças e adolescentes [School engagement and depression: a correlational study with children and adolescents] (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Universidade Federal da Paraíba, João Pessoa, Brasil. [ Links ]

Granville-Garcia, A. F., Souza, M. G. C., Menezes, V. A., Barbosa, R. & Cavalcanti, A. L. (2009). Conhecimentos e percepção de professores sobre maus-tratos em crianças e adolescentes [Teachers' knowledge and perceptions of children's and adolescents' abuse]. Saúde e Sociedade, 18(1), 131-140. doi: 10.1590/S0104-12902009000100013 [ Links ]

Hawker, D., & Boulton, M. (2000). Twenty years' research on peer victimization and psychosocial maladjustment: A meta-analytic review of cross-sectional studies. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry & Allied Disciplines, 41, 441-455. doi: 10.1111/14697610.00629 [ Links ]

Hong, J. S., & Espelage, D. L. (2012). A review of research on bullying and peer victimization in school: An ecological system analysis. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 17, 311-322. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2012.03.003 [ Links ]

Khoury-Kassabri, M., Benbenishty, R., Astor, R. A., & Zeira, A. (2004). The contributions of community, family, and school variables to student victimization. American Journal of Community Psychology, 34(3), 187-204. doi: 10.1007/s10464-004-7414-4 [ Links ]

Kumpulainen, K., Rãsánen, E., Henttonen, I., Almqvist, F., Kresanov, K., Linna, S. L., . . . Tamminen, T. (1998). Bullying and psychiatric symptoms among elementary school-age children. Child Abuse and Neglect, 22(7), 705-717. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(98)00049-0 [ Links ]

Lev-Wiesel, R., & Sternberg, R. (2012). Victimized at home revictimized by peers: Domestic child abuse a risk factor for social rejection. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 29(3), 203-220. doi: 10.1007/s10560-012-0258-0 [ Links ]

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. (2014). Education at a Glance: 2014. Paris, France: OECD Publishing. Retirered from http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eag-2014-en [ Links ]

Olweus, D. (2013). School bullying: development and some important challenges. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9, 751-780. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185516 [ Links ]

Pasqualli, L., Gouveia, V. V., Andriola W. B., Miranda, F. J., & Ramos, A. L. M. (1996). Questionário de Saúde Geral de Goldberg [Goldberg's General Health Questionnaire]. Casa do Psicólogo: São Paulo. [ Links ]

Pinheiro, F. M. F., & Williams, L. C. A. (2009). Violência intrafamiliar e envolvimento em bullying no ensino fundamental [Family violence and bullying in the primary school]. Cadernos de Pesquisa, 39(138), 995-1018. doi: 10.1590/S0100-15742009000300015 [ Links ]

Reid, R. J., Peterson, N. A., Hughey, J., & Garcia-Reid, P. (2006). School climate and adolescent drug use: Mediating effects of violence victimization in the urban high school context. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 27(3), 281-292. doi: 10.1007/s10935-006-0035-y [ Links ]

Roland, E., & Midthassel, U. V. (2012). The zero program. New Directions of Youth Development, 133, 29-39. doi: 10.1002/yd.20005 [ Links ]

Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Salanova, M. (2006). The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 66, 701-716. doi: 10.1177/0013164405282471 [ Links ]

Schreck, C. J., Miller, J. M., & Gibson, C. L. (2003). Trouble in the school yard: A study of the risk factors of victimization at school. Crime & Delinquency, 49(3), 460-484. doi: 10.1177/001112870304900300 [ Links ]

Scotta, C., Bejo, C. (Producers), & Cantet, L. (Director). (2008). Entre lês Murs [Motion picture]. França: Canal plus. [ Links ]

Sela-Shayovitz, R. (2009). Dealing with school violence: The effect of school violence prevention training on teachers 'perceived self-efficacy in dealing with violent events. Teaching and teacher education, 25(8), 1061-1066. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2009.04.010 [ Links ]

Singh, G. K. & Ghandour, R. M. (2012). Impact of neighborhood social conditions and household socioeconomic status on behavioral problems among US children. Maternal and Child Health Journal 16(1), 158-169. doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-1005-z [ Links ]

Smith, P. K., & Shu, S. (2000). What good schools can do about bullying: Findings from a survey in English schools after a decade of research and action. Childhood, 7(2), 193-212. doi: 10.1177/0907568200007002005 [ Links ]

Stelko-Pereira, A. C. (2012). Avaliação de um programa preventivo de violência escolar: planejamento, implantação e eficácia [Evaluation of a school violence preventive program: development, implementation and efficacy] (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Universidade Federal de São Carlos, Brasil. Retrieved from http://www.laprev.ufscar.br/documentos/arquivos/teses-e-dissertacoes/tese-ana-carina.pdf [ Links ]

Stelko-Pereira, A. C., Albuquerque, P. P., & Williams, L. C. A. (2012). Percepção de alunos sobre a atuação de funcionários escolares a situações de violência [Perception of students about responses of school staff in situations of school violence]. Revista Eletrônica de Educação, 6(2), 376-391. Retrieved from http://www.reveduc.ufscar.br/index.php/reveduc/article/viewFile/277/207 [ Links ]

Stelko-Pereira, A. C., & Williams, L. C. A. (2012). Teacher's mental health and school violence in two Brazilian schools [Abstract]. International Journal of Psychology, 47, 596-596. doi: 10.1080/00207594.2012.709118. [ Links ]

Stelko-Pereira, A. C., & Williams, L. C. A. (2013a). School violence association with income and neighborhood safety in Brazil. Children, Youth and Environments, 23(1), 105-123. Retrieved from: www.jstor.org/action/showPublication?journalCode=chilyou tenvi [ Links ]

Stelko-Pereira, A. C., & Williams, L. C. A. (2013b). "Psiu, repara aí": Avaliação de folder para prevenção de violência escolar ["Psiu, repara aí": Evaluation of a brochure to prevent school violence]. Psico-USF, 18(2), 329-332. doi: 10.1590/S1413-82712013000200016 [ Links ]

Stelko-Pereira, A. C., Williams, L. C. A., & Freitas, L. C. (2010). Validade e consistência interna do Questionário de Investigação de Prevalência de Violência Escolar - versão estudantes [Validity and internal consistency of the School Violence Prevalence investigation questionnaire -student version]. Avaliação Psicológica, 9(3), 403-411. Retrieved from http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext & pid=S1 677-04712010000300007 & lng=pt & tlng=pt [ Links ]

Stephens, N., Mastrosimone, W., Gabler, D. (Producers), & Ferland, G. (Director) (2002). Bang Bang You're dead [Motion Picture]. EUA: Every guy production. [ Links ]

Strohmeir, D., & Noam, G. G. (2012). Bullying in schools: What is the problem, and how can educators solve it? New directions of youth development, 133, 7-13. doi: 10.1007/s11292-010-9109-1 [ Links ]

Tingstrom, D. H., Sterling-Tuner, H. E., & Wilczynski, S. M. (2006). The good behavior game: 19692002. Behavior Modification, 30(2), 225-253. doi: 10.1177/0145445503261165 [ Links ]

Ttofi, M. M., & Farrington, D. P. (2011). Effectiveness of school-based programs to reduce bullying: A systemic and meta-analytic review. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 7(1), 27-56. doi: 10.1007/s11292-010-9109-1 [ Links ]

United Nations Development Program (2013). The rise of the South: Human Progress in a Diverse World. New York: United Nations Publishing. Retrieved from http: http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/reports/14/hdr2013_en_complete.pdf [ Links ]

Warner, B. S., Weist, M. D., & Krulak, A. (1999). Risk factors for school violence. Urban Education, 34(1), 52-68. doi: 10.1177/0042085999341004. [ Links ]

Webster-Stratton, C. (2000). The Incredible Years Training Series. Juvenile Justice Bulletin, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, Washington, DC. [ Links ]

Welsh, W. N. (2003). Individual and institutional predictors of school disorder. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 1(4), 346-363. doi: 10.1177/1541204003255843 [ Links ]

Williams, L. C. A., & Stelko-Pereira, A. C. (2013a). Let's prevent school violence, not just bullying and peer victimization: A commentary on Finkelhor, Turner, and Hamby. Child Abuse and Neglect, 37, 235-236. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.10.006 [ Links ]

Williams, L. C. A., & Stelko-Pereira, A. C. (Eds.) (2013b). Violência nota zero: Como aprimorar as relações na escola [Violence F Minus: How improve interpersonal relationships at school]. São Carlos: Eduf. [ Links ]