1. Introduction

Collaboration between different actors is key to achieving sustainable development, something recognized internationally in the UN Sustainable Development Goals in its objective 17 "Partnerships for the Goals" (United Nations, 2015). At the global level, the governments of nation-states maintain close collaboration with businesses and NGOs to arrive at the definition of the Sustainable Development Goals (Gasper, 2019). Likewise, at the national and subnational level, intersectoral collaboration networks are established, which seek to address challenges related to economic development, education, health, poverty reduction, strengthening community ties, and environmental sustainability (Selsky & Parker, 2005).

Roberts and Bradley (1991) have understood stakeholder collaboration focused on solving social problems as the temporary social arrangement in which different individual and organizational social actors work together towards a common goal (in this case, sustainable social development). In the process, they transform materials, ideas and social relations. From this perspective, intersectoral collaboration (government, private initiative and organized civil society) emphasizes the effects of the multiple and complex interdependencies required to achieve significant changes that promote sustainable social development. Moreover, this involves multiple stakeholders taking part in negotiations, planning, and implementing strategies to achieve their development goals.

Achieving alliances between different sectors and stakeholders entails important challenges. First, in the search for convergence around defined goals and the required strategies to accomplish them, the process of reaching agreements on the desired results often faces obstacles. This is due, in part, to the pluralism of values and different worldviews of the stakeholders involved, for which the adoption of the counterparts’ perspectives is suggested to channel conflicts and guide the negotiations of goals toward consensus (Guba & Lincoln, 1989). Similarly, in alliances for sustainable social development, the power imbalance between the actors can lead to the imposition of agendas and reaffirm inequalities in the distribution of benefits that the actors receive from their involvement in those alliances (Mert & Chan, 2012). NGOs, which are part of organized civil society, face significant difficulties in achieving development goals due to their lower operational capacity and lower sphere of influence when compared to the private initiative and the governmental sphere. Likewise, they are more affected by the power asymmetries in development alliances, something reflected in the control of financial flows exercised by donors (Reith, 2010).

Yan et al. (2018) argued that NGOs are central stakeholders in reaching socially sustainable development because they perform a variety of roles, such as consultant, capacity builder, broker and communicator, leader, advocate, and monitor, among others. NGOs are recognized as key actors given their growing role in community engagement activities, service provision, and public policy formulation, particularly in Latin America, where they function as organizational mechanisms that allow citizens to influence the development of their socio-political context (Hochstetler & Friedman, 2008). This is the case for Ecuador: the design and implementation of projects that involve funding partners decrease NGO accountability to beneficiaries and focus more on reporting results to donors. For this reason, it has been suggested that closer relationships between NGOs and municipal governments can enhance the actions taken to meet development goals without having to diminish their legitimacy with local stakeholders. This is because NGOs can complement governments by building capabilities in communities and offering specialized technical assistance (Keese & Freire-Argudo, 2006). Likewise, it has been argued that expanding NGO alliances to form NGO networks and increasing alliances with universities allow the NGOs’ organizational objectives to advance, thereby increasing their legitimacy (Appe, 2016; Appe & Barragán, 2017).

While the reason for establishing alliances and collaboration in the context of socially sustainable development is clear, the role of conflict has been comparatively underexplored. When it comes to conflict, more attention is paid to the field of international relations and how geopolitical conflicts prevent effective cooperation (Mac Ginty & Williams, 2016). Conflict occurring at the subnational level is often described in terms of social conflict, where social movements challenge economic and social policies, as well as infrastructure projects, in an attempt to mitigate environmental and social damages (López & Vértiz, 2015; Pérez-Rincón, 2014). Yet, studies that address conflict within a stakeholder network at the subnational level, particularly in the context of sustainable development, are rare (Calvano, 2008; Schepers, 2006). These few studies commonly adopt a neutral, comprehensive approach, outlining how conflict develops throughout the network and how it precludes decisive action. Studies that predominantly address the subject of conflict in a stakeholder network from the perspective of the NGO, however, are virtually non-existent.

It can thus be stated that it is imperative in strategic administration issues for NGOs aimed at solving social problems to carry out studies that allow them to know the possible evolution of their alliances and potential emerging conflicts towards a foreseen future horizon. Adopting the perspective of local NGOs provides an opportunity to understand how collaboration and conflict dynamics in the context of sustainable social development unfold at the grassroots level. Focusing on the role of alliances and conflicts as seen from the perspective of NGOs can also reveal power relations that are often hidden when taking a macro-level, international perspective, or a comprehensive, neutral perspective. Based on this, NGOs will be able to visualize the continuities, tensions, and changes in their relationships with other strategic actors for sustainable social development. This would also enable them to anticipate dependencies and influences about other stakeholders and to design plans that reduce their weaknesses and amplify their strengths.

This study focuses on the Fundación de Acción Social Cáritas in Ecuador, an NGO of great relevance for the Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas province. Due to its coverage capacity, diversity of services, and multiplicity of current social programs, it is appropriate as a focal organization of analysis to illustrate the convergences and divergences that it might experience in the future with its network of stakeholders.

In the current context, Fundación de Acción Social Cáritas faces serious hardships in its operations due to the economic, social, and public health blows derived from the COVID-19 pandemic, and it saw many of its stakeholder alliances dissolved. Some of the donors and funding entities reduced their financial support due to the pandemic-related economic crisis. This, in turn, resulted in an increase in fees that the organization asks in return for their services, the delay in technological renovation plans, and the loss of human resources that offered their services at low prices. Similarly, beneficiaries of Fundación de Acción Social Cáritas have stopped their attendance to the services and programs of the organization in an attempt to reduce their financial expenses.

Given these circumstances, this future-centered research can help the Fundación de Acción Social Cáritas to anticipate future disruptive events such as the current pandemic and strengthen its strategic planning to preserve, increase, and diversify its allies for sustainable social development, on the one hand, and adapt their services in such a way that they can adapt to contexts of uncertainty and simultaneously maintain their value for the beneficiary stakeholder groups, on the other hand. Using Fundación de Acción Social Cáritas as a case study, we seek to answer: How does a Futures Studies perspective on stakeholder alliances and conflicts help an NGO to prepare for the future? And how does an NGO benefit from foreseeing the convergences and divergences in the network of stakeholders in the context of sustainable social development? This study contributes to the literature on strategic management of NGOs by illustrating how Futures Studies methods can strengthen the design and execution of management strategies for sustainable social development.

This article first addresses the relevance of stakeholders for organizational development. The statistics and Futures Studies methods used in this research are explained, especially the K expert competence coefficient and the MACTOR method.

Then, the research results are presented according to the final expert panel used to foresee the convergences and divergences between stakeholders. The histogram of power relations and stakeholder networks of convergences and divergences are also included. Finally, some conclusions are presented, which emphasize the contributions of Futures Studies to the Fundación de Acción Social Cáritas and the future perspectives on the role of this NGO within a stakeholder network.

NGOs’ Stakeholder Networks: Alliances and Conflicts for Sustainable Development

Because the process of reaching sustainable social development is characterized by complexity and volatility, actors from different spheres are required to participate in development initiatives: business, public sector, and civil society are the traditional three spheres, but one can also include academia, international organizations, and grassroots movements, among others. These different actors join together in multi-stakeholder partnerships, which aim to build operational capacity by developing and leveraging the perspectives and resources of the partner organizations (Clarke & MacDonald, 2019). A common role for NGOs in cross-sector, multi-stakeholder partnerships is that of mediator, where they channel conflicts between social groups and organizations, for instance, when they mitigate conflicts between workers and employer organizations due to poor working conditions (Martin, 2012). Another commonly held role by NGOs is that of connecting different actors, such as governments, private organizations, and research groups (Sharma et al., 1994). When partnering with corporations, Baur & Palazzo (2011) argue that NGOs acquire a special status that grants such alliances legitimacy, and that is because the NGOs are deemed to be acting on behalf of the common good. This resonates with the argument of Clarke and Fuller (2010), who go beyond the assertion that NGOs by themselves bring moral legitimacy to multi-stakeholder partnerships and suggest that they play a convener role by bringing together different legitimate stakeholders to solve a common issue.

Yan et al. (2018) differentiate between enabling, coordinating, and facilitating roles of NGOs’, and these different roles have different implications for whether NGOs favour strategic alliance formation or the appearance of conflict within multistakeholder partnerships. For instance, the role of advocate, which is a facilitating role, can strengthen alliances on a certain topic when the NGO brings together different actors with similar viewpoints. The same advocate role, however, can create disputes when the NGO holds a different perspective on a sustainable development issue, and therefore generate tensions in the multistakeholder partnership (Choup, 2006).

Conflicts in multi-stakeholder partnerships can arise due to the complexity of organizing different organizations and interests towards a single goal. Where the number of partners is large, the strategic priorities of each partner in the network are subordinated to the larger goals of the partnerships (Jörby, 2002). In these cases, conflicts emerge because the process to accomplish the goals of each partner was not discussed in advance, only the process of achieving the collective interest (Clarke & MacDonald, 2019). Local-level NGOs are often at a disadvantage in conflicts regarding the strategic interests of the partner organizations, because they may lack the financial or technical resources to accomplish the collective goal on their own. In such cases, they become reliant on other partners in the network, and the long-term implications of this reliance may include reduced autonomous operational capacity, diminished influence in policy formulation, and limited impact of their activities.

Stakeholders in organizational development: A Futures Studies perspective

Recognizing the importance of stakeholders for the unfolding of organizational strategies and actions helps develop a more rigorous strategic planning process and has a greater probability of success in achieving the established plans. In Futures Studies, stakeholder participation is key. Via dialogue and negotiation, scenario planning can translate into actionable knowledge and can help both the stakeholders and the focal organization reach mutual understanding and learning (Oliver, 2023). This, in turn, facilitates the implementation of prospective processes in organizations, which can reach some degree of legitimacy by engaging with internal and external stakeholders (Saritas et al., 2013). The relationships with stakeholders constitute a core attribute of the organizational identity, with the relationships that a focal organization maintains with internal and external agents, remaining closely coupled with each other (Brickson, 2005). Specific relationship patterns maintained with stakeholders offer unique value to organizations in promoting certain sets of social values and transforming their environment (Brickson, 2007). Within a prospective process, therefore, it is critical to identify how the relationships with stakeholders will be managed and to foresee their potential evolution. This can help increase the success possibilities of an organization and of the services it offers.

Previous research has indicated that the knowledge obtained from the commitment toward internal and external stakeholders contributes to the organization’s orientation toward sustainable innovation, but this knowledge must be managed internally to turn it into new ideas for innovation (Ayuso et al., 2011). In the case of organizations dedicated to development, particularly NGOs, the creative proposals and solutions that they can contribute derive largely from the relationships they seek to maintain with stakeholders in their environment and with international agencies, with whom they seek to form alliances for development (Lewis, 2001). It is to be expected that each stakeholder will have objectives and plans of their own, some of which will advance the interests of a focal organization and others that will obstruct its progress. Identifying these objectives and the possible actions to be taken by the organizations’ stakeholders to achieve them, as well as their effects on the focal organization, is one of the strengths of the French School of Futures Studies, which is characterized by a strong strategic component and its exploratory approach in the design of plans for reaching a desired future (Zeraoui y Farías, 2011).

From the methodological approaches of the French School of Futures Studies, the MACTOR method allows researchers to foresee the positions of stakeholders in a future scenario, identifying the convergences and divergences between them. Likewise, the method offers organizations the possibility of locating the different stakeholders on a plane of influences and dependencies and acting accordingly. Similarly, though the evidence is limited, scenario planning has been suggested as possibly enabling organizational agility if certain conditions are met, like designing scenarios from a systemic perspective and giving time to an organization’s decision-makers to absorb the insights gained from a foresight process (Chermack et al., 2019). In the context of sustainable development, these benefits might improve an organization’s performance and capacity to achieve its goals.

According to Camelo (2014), this plane of influence has four sections where stakeholders are classified according to their ability to influence other actors. In the upper left quadrant, the power zone, are the dominant actors who have great influence and low dependence on the issue under analysis. The upper right quadrant is the conflict zone, where the liaison actors are located, whose clash can have major effects on the development of events. In the lower right quadrant, also called the area of dominated actors, you can find those who are subject to the actions of more powerful actors and have a low level of influence on the key issue. Finally, in the lower left quadrant is the zone of autonomous actors, where there are actors who are predominantly independent of the system but with a significant share of power.

In the context of development NGOs, outlining this plan with the relevant stakeholders can facilitate their operations because they will be able to visualize the relationships between stakeholders in the environment and their possible effects, which will contribute to the design of a more accurate and detailed strategy for achieving their goals.

2. Methodology

This research constitutes a mixed methodological approach, since, in terms of Cruz-Aguilar and Medina-Vásquez (2015), the MACTOR method (Matrix of Alliances and Conflicts: Tactics, Objectives, and Recommendations) is one of the qualitative-quantitative methods of descriptive scope in Futures Studies. It is most used in the French School and it is characterized by its potential to determine the power relations between stakeholders, as well as the convergences and divergences that exist when trying to successfully face future challenges in a system.

Similarly, as mentioned by Pimienta and De la Orden (2017), the methodological approach is not experimental, since the phenomena under scrutiny are studied in their context of origin and without generating deliberate changes in the study variables. Additionally, Gándara and Osorio-Vera (2017) emphasize the need to integrate a panel of experts that contributes, through collective deliberation processes, to the assignment of numerical weights that will be analyzed with the support of the software package developed by LIPSOR (Laboratory for Investigation in Prospective Strategy and Organisation).

According to Hernández et al. (2023), the software developed by this laboratory allows for collecting the opinions of experts through different weighing scales. This represents an advantage compared to the tools generated by other Futures Studies Schools because it facilitates the transition from qualitative inputs to quantitative and comparable results. In addition, Hernández and Hurtado-Hurtado (2020b), highlight the benefits of the software belonging to LIPSOR, especially when performing an analysis of the actors using the MACTOR method, since they have the only computer program that encompasses the force and the position of the actors regarding a set of long-term goals.

Formation of the expert panel

Zartha-Sossa et al. (2019) point out that Futures Studies methods require two types of agents for their development: futures researchers and experts in the field of study. The contribution of the latter consists of issuing informed opinions to increase the systemic understanding of an organization. Thus, as suggested by Matheus-Marín et al. (2018), an instrument was used to determine the expert competence coefficients K of 15 potential experts.

To analyze the expert competence coefficients K, it is necessary to measure the knowledge and argumentation coefficients of potential experts. The former was obtained through a self-assessment concerning the level of knowledge on the topic of consultation and was measured in the form of an ascending scale (1 minimum and 10 maximum), according to the level of mastery of the subject under study. For the latter, the relevance fell on the theoretical analyses carried out by the experts, the experience obtained in their professional activity, the studies of national and foreign authors that they have reviewed, their knowledge about the state of the problem to be addressed, and their intuition about the topic, as recommended by Matheus-Marín et al. (2018).

Following the guidelines of the study carried out by Cruz-Ramírez and Martínez-Cepena (2020), the following classification ranges were used: high coefficient (0.8 <K <1.0), medium coefficient (0.5 <K <0.8) and low coefficient (K <0.5). Therefore, to form the panel of experts used in this study, only those who obtained a high K coefficient of competence were considered, giving way to the structuring of a coalition with academics, businessmen, public officials, and collaborators of Fundación de Acción Social Cáritas. Hence, as Meijering and Tobi (2016) indicate, a multidisciplinary expert panel was formed, which favored participatory reflection with high levels of learning.

Stakeholder identification

For the stakeholder identification phase, a first participatory round was carried out in the panel of experts. Following the guidelines of Oberholster and Adendorff (2018), the participating experts were asked to make a first list with tentative actors from four key sectors: academy, community, government, and the private sector. These actors, according to Hernández et al. (2023), must correspond to organizations or groups with the power to influence the mission, projects, or daily activities of the organization under study. Similarly, those who may be affected at the same levels by the organization of interest are considered.

After this, in a second participatory round, an electronic consultation tool was used to filter the initial list which intended to remove the stakeholders that do not have a greater impact on the NGO. When measuring the reliability of the instrument, a Cronbach's alpha coefficient equal to 0.887 was obtained, which, in agreement with Cervantes (2005), suggests a high consistency between the items. Therefore, the application of the following scale was considered valid: 1 (totally agree), 2 (partially agree), 3 (neutral), 4 (partially disagree) and 5 (totally disagree).

Moreover, as suggested by Ramírez-Ríos y Polack-Peña (2020), Kendall's W test was applied to identify the level of agreement between the expert opinions. To establish the definitive list of stakeholders, only those who obtained a mean and a mode equal to or greater than 2 and 1 respectively were accepted, since the applied consultation instrument reflects the representativeness of the stakeholders according to the averages and frequencies of the numerical weightings made by the panel.

Using the MACTOR method

To determine the power relations between stakeholders, as well as their convergences and divergences about future challenges for the NGO, the mixed Futures Studies method MACTOR was chosen. Chung-Pinzás (2017) highlights the advantage MACTOR offers when ordering the information in mathematical matrices that relate the stakeholders with the strategic objectives for the long term through the use of specialized software. For this, as Quinteros and Hamann (2017) point out, it is necessary to define a long title and a representative code to register them in the MACTOR version 5.1.2 computer program, offered by LIPSOR.

The Direct Influence Matrix was completed by expert-estimated numerical weighting based on the levels of influence between stakeholders. Specifically, the importance of the effect or impact of one actor on another and their equivalences was assessed: they correspond to 0 = No influence, 1 = Processes, 2 = Projects, 3 = Mission, and 4 = Existence. Therefore, 870 relationships between stakeholders were compared, which are defined by all possible combinations, minus the 30 unacceptable relationships of a stakeholder with himself, that is [(30 x 30) - 30] = 870. Moreover, in the Matrix of Valued Positions, the position of each actor concerning the objectives was assessed individually. To do this, we worked with signs and numbers, depending on whether the actor was favorable or opposed to the analyzed objective.

Finally, the 9 strategic objectives of the NGO for the year 2035 were defined, according to the strategic variables identified in the previous study by Hernández and Hurtado-Hurtado (2020a). Finally, the evaluations were carried out together with the group of experts for the Matrix of Valued Positions of stakeholders on objectives (2MAO).

3. Findings

The findings obtained during the methodological process begin with the formation of the expert panel. Thus, with the application of an instrument focused on the K competence coefficients, it was possible to classify potential experts. An outstanding result was that three of the fifteen participants obtained an average grade, that is, between 0.5 and 0.8. On the other hand, the remaining twelve presented scores higher than 0.85 and were invited to take part in the participatory workshops (Table 1). Consequently, the panel of experts has an average coefficient equal to 0.89, which makes it possible to assert that the collective reflection and deliberation exercises were developed under the consensus of a multidisciplinary group and with an opinion formed and specialized in the field.

Table 1 Expert panel formation.

| Potential expert | Knowledge coefficient (Kc) | Reasoning coefficient (Ka) | K competence coefficient (K) | Grade |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0,7 | 0,8 | 0,75 | Medium |

| 2 | 1 | 0,9 | 0,95 | High |

| 3 | 0,8 | 0,9 | 0,85 | High |

| 4 | 0,8 | 0,9 | 0,85 | High |

| 5 | 0,9 | 0,9 | 0,9 | High |

| 6 | 0,6 | 0,7 | 0,65 | Medium |

| 7 | 0,8 | 1 | 0,9 | High |

| 8 | 0,8 | 0,9 | 0,85 | High |

| 9 | 1 | 0,9 | 0,95 | High |

| 10 | 0,5 | 0,7 | 0,6 | Medium |

| 11 | 0,8 | 0,9 | 0,85 | High |

| 12 | 0,9 | 0,9 | 0,9 | High |

| 13 | 0,9 | 0,9 | 0,9 | High |

| 14 | 0,9 | 0,8 | 0,85 | High |

| 15 | 0,8 | 1 | 0,9 | High |

Note. The formula to estimate the K competence coefficients is 𝐾=1/2 (𝐾𝑐+𝐾𝑎) .

Source: own elaboration based on the results of the expert panel.

During the second participatory round, the filtering instrument was applied. The opinion of the experts decided on the removal of two stakeholders from the initial list (Table 2). In both cases, this was because the two stakeholders had very low levels of influence and dependence to be able to bring about any change in Fundación de Acción Social Cáritas. As a means of corroborating the expert consensus, the Kendall W statistical test (Table 3) was applied, obtaining as a result a value equal to 0.883, which suggests that there is a significant level of agreement between the opinions of the experts. Hence, an additional workshop was not necessary to increase uniformity in the experts’ numerical weightings.

Table 2 Results after filtering the initial list of stakeholders.

| Potential stakeholders | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | ||

| Numerical weightings assigned by experts | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 6 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 7 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 8 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 9 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 10 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 11 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 12 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Median | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Mode | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

Source: own elaboration based on the results of the expert panel.

Table 3 Calculating the agreement coefficient.

| N | 12 |

|---|---|

| Kendall’s Wa | 0,883 |

| Gl | 31 |

| Asymptotic significance | 0,000 |

| Kendall rank correlation coefficient | |

Source: SPSS Software version 26.0

When obtaining the definitive list of stakeholders (Table 4), it was found that the 30 that were identified correspond to human groups with the capacity to condition the systemic evolution of the NGO based on their degree of domination or individual submission, as well as the product of convergences and divergences that arise from the affinity of their institutional purposes or their social interests. On the other hand, the premise of Oberholster and Adendorff (2018)is fulfilled, as a notable presence of four key sectors is observed: academia, communities, government and private sector. However, as Quinteros and Hamann (2017) highlight, each system incorporates to its stakeholder analysis those that are fundamental for the normal operations of the organization. In this case, what has been said is supported by the presence of entities related to the Catholic Church and the international deployment of Caritas with centers in 146 countries.

Table 4 Filtered list of stakeholders

| N° | Long Title | Code |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Academia | AC |

| 2 | Strategic allies | AE |

| 3 | Partner Assembly of Fundación de Acción Social Cáritas | AS |

| 4 | National Assembly of Ecuador | ANE |

| 5 | Cáritas Internacionalis | CI |

| 6 | Ecuadorian Committee of the Interamerican Commission for Women | CECIM |

| 7 | Ecuadorian Episcopal Conference | CEE |

| 8 | Council for Childhood and Adolescence | CCNA |

| 9 | Cooperantes fraternos (private donors) | CF |

| 10 | Diocese of Santo Domingo | DSD |

| 11 | Executives of Bancos Comunales (financial organizations similar to community banks) | DBC |

| 12 | Private Enterprises | EP |

| 13 | Municipality of Santo Domingo | GM |

| 14 | Santo Domingo Prefecture (autonomous, decentralized government of Santo Domingo) | GP |

| 15 | Governorate Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | GSD |

| 16 | National Institute of Statistics and Censuses | INEC |

| 17 | National Institute for Children and the Family | INNFA |

| 18 | Ministry of Culture | MC |

| 19 | Ministry of Education | ME |

| 20 | Ministry of Social and Economic Inclusion | MIES |

| 21 | Ministry of Foreign Relations and Human Mobility | MREMH |

| 22 | Ministry of Labor | MT |

| 23 | Professionals external to Fundación de Acción Social Cáritas | PE |

| 24 | Suppliers | PR |

| 25 | Human Rights Secretariat | SDH |

| 26 | National Secretariat of Planning | STPE |

| 27 | Catholic Service of the Church | SCI |

| 28 | Organized Civil Society | SCO |

| 29 | Council for the Protection of Human Rights | CCPD |

| 30 | Volunteers | VO |

Source: Own elaboration.

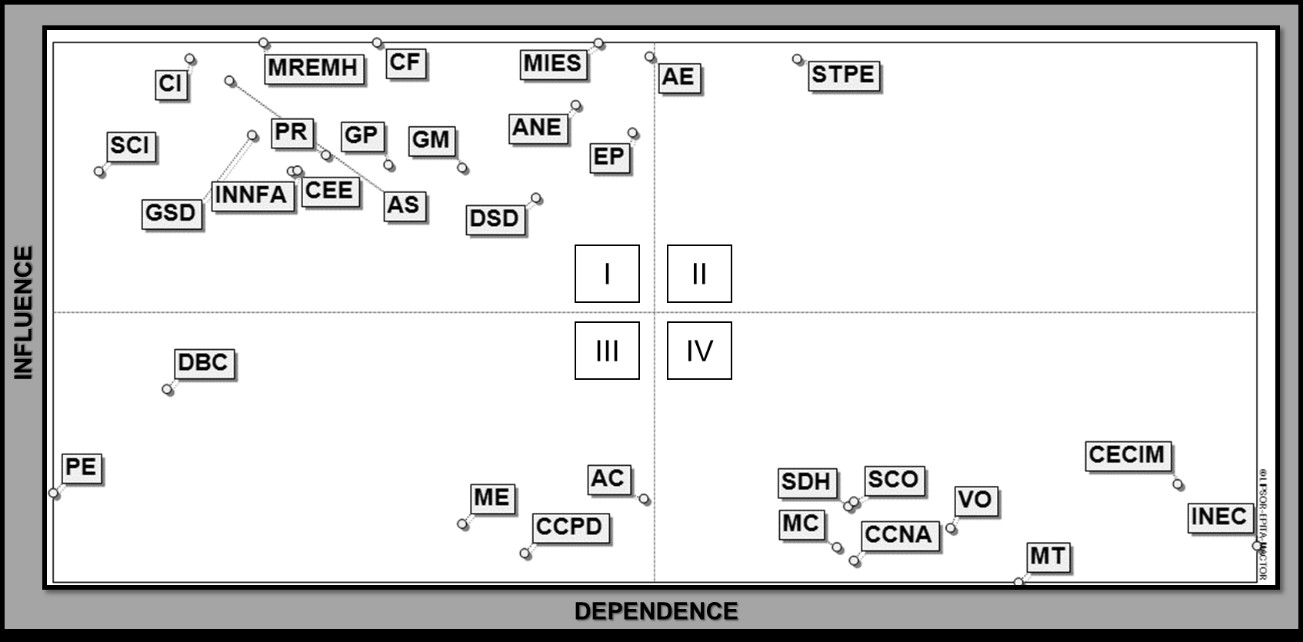

The participatory workshop led to the elaboration of the Matrix of Direct Influences (Table 5). The influence and dependencies plane between stakeholders was obtained from this Matrix (figure 1). This visual input has a high potential value in defining stakeholders, as the quadrant in which each stakeholder falls defines their condition within the system under study. Thus, according to the distribution of stakeholders in this plane resulting from the software work and the methodological guides of Camelo (2014), four classifications were obtained: dominant, liaison, autonomous and dominated.

Table 5 Matrix of Direct Influences.

| MID | AC | AE | AS | ANE | CI | CECIM | CEE | CCNA | CF | DSD | DBC | EP | GM | GP | GSD | INEC | INNFA | MC | ME | MIES | MREMH | MT | PE | PR | SDH | STPE | SCI | SCO | CCPD | VO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AC | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| AE | 3 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| AS | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| ANE | 2 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| CI | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| CECIM | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| CEE | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| CCNA | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| CF | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| DSD | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| DBC | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| EP | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| GM | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| GP | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| GSD | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| INEC | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| INNFA | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| MC | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| ME | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| MIES | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| MREMH | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| MT | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| PE | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| PR | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| SDH | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| STPE | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| SCI | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| SCO | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| CCPD | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| VO | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

Source: MACTOR Software version 5.1.2.

Source: MACTOR Software version 5.1.2.

Figure 1 Plane of influences and dependencies among stakeholders.

Dominant actors: Quadrant I

They are characterized by their high influence and low dependence in relation to the other stakeholders under study. In this case, 16 of the 30 stakeholders are dominant: (SCI), (CI), (GSD), (CEE), (AS), (MREMH), (PR), (INNFA), (CF), (GP), (GM), (ANE), (MIES), (DSD), (EP) and (AE).

Liaison actors: Quadrant II

They are the stakeholders with the ability to increase or decrease the level of conflict within the system due to their high levels of influence and dependence. As can be seen in the plan, only one of the stakeholders complies with this characteristic: (STPE).

Autonomous actors: Quadrant III

Stakeholders with low levels of influence and dependence are located in this quadrant. They are those who are not affected by the decisions of other involved stakeholders, but who cannot influence them either. According to the stakeholder distribution obtained in the plane, the 5 autonomous stakeholders of the system are: (PE), (DBC), (ME), (CCPD) and (AC).

Dominated actors: Quadrant IV

The stakeholders listed in this quadrant are relevant to the system, not because of what they promote in it, but because of their high level of dependency and the ease with which the most influential stakeholders can control them for their purposes. The findings suggest that the following stakeholders fall into the dominated category: (SDH), (MC), (SCO), (CCNA), (VO), (MT), (CECIM), (INEC).

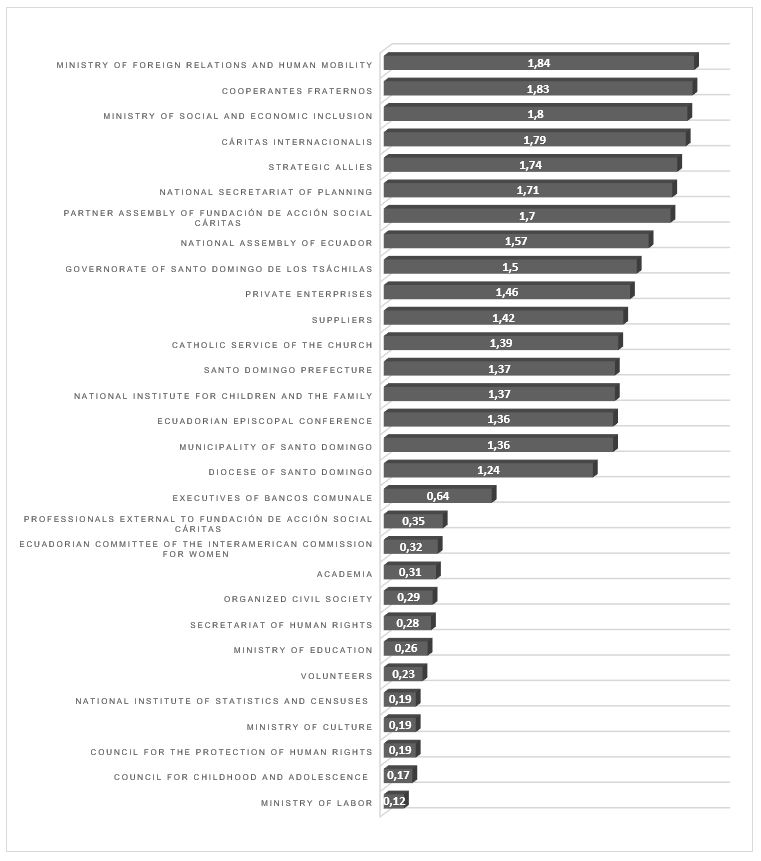

Once the stakeholders have been classified, the determination of the Qi power relations is essential. According to Chung-Pinzás (2017), Qi expresses the actor's power relationships taking into account his maximum of direct and indirect influences and dependencies and their feedback. Therefore, according to the results obtained (Annex 1), the strongest stakeholders in the study system are: Ministry of Foreign Relations and Human Mobility (Qi = 1,84), Cooperantes Fraternos (Qi = 1,83), Ministry of Social and Economic Inclusion (Qi = 1,8), Cáritas Internacionalis (Qi = 1,79), and Strategic Allies (Qi = 1,74). In contrast, the weakest stakeholders are: Council for the Protection of Human Rights, Ministry of Culture and the National Institute of Statistics and Censuses (all three with Qi = 0,19), Council for Childhood and Adolescence (Qi = 0,17), and the Ministry of Labor (Qi = 0,12).

These results coincide with the statements of Lewis (2001), because the stakeholders who have the greatest power over the system come, in the first instance, from within the organization; then, from their closest environment and, finally, from abroad. Likewise, they correspond to those that legitimize the existence of Fundación de Acción Social Cáritas, due to its requirement to obtain the necessary permits from the government to carry out its operations. There are also those responsible for the financing and management of the NGO’s operations through local donations and economic funding from international organizations. In contrast, stakeholders with less power include public entities with little influence to restrict or influence the activities of the NGO, given that they are not regulators or providers of any kind of resources.

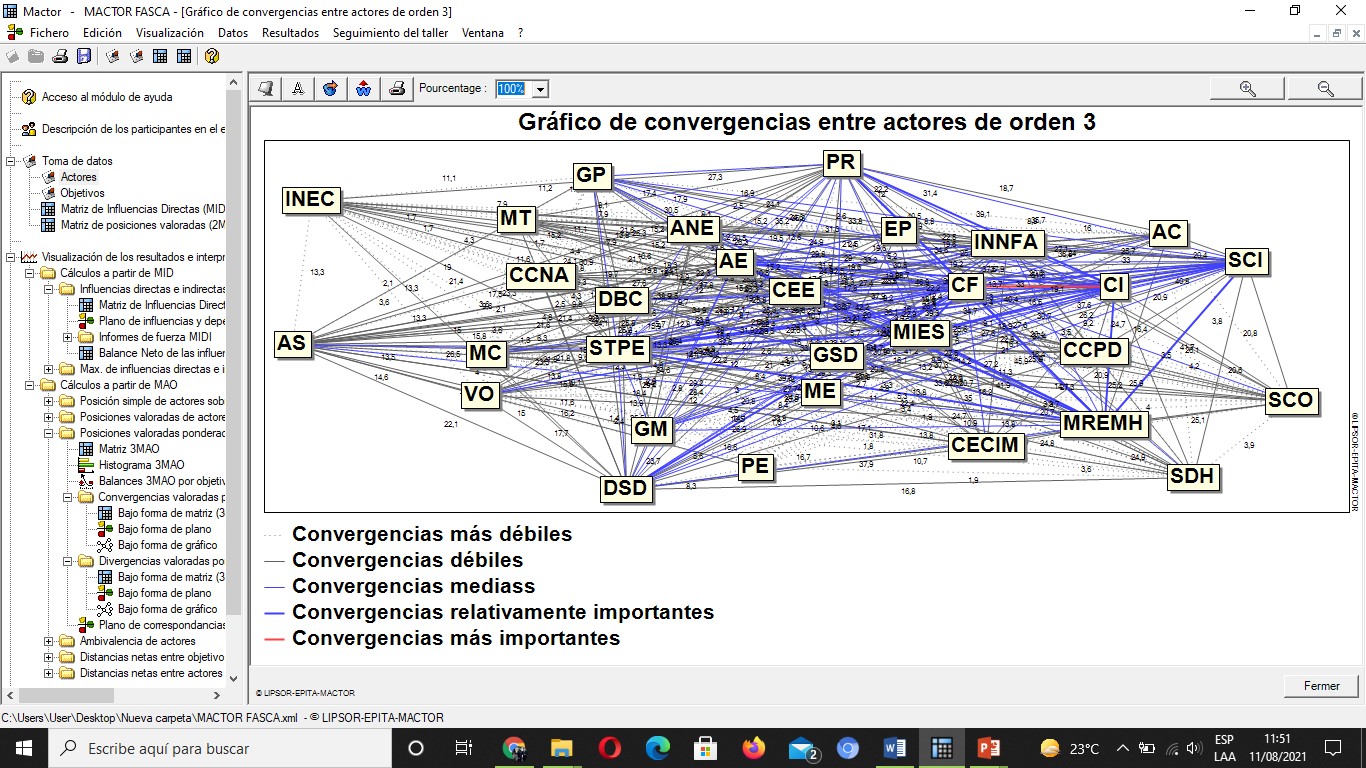

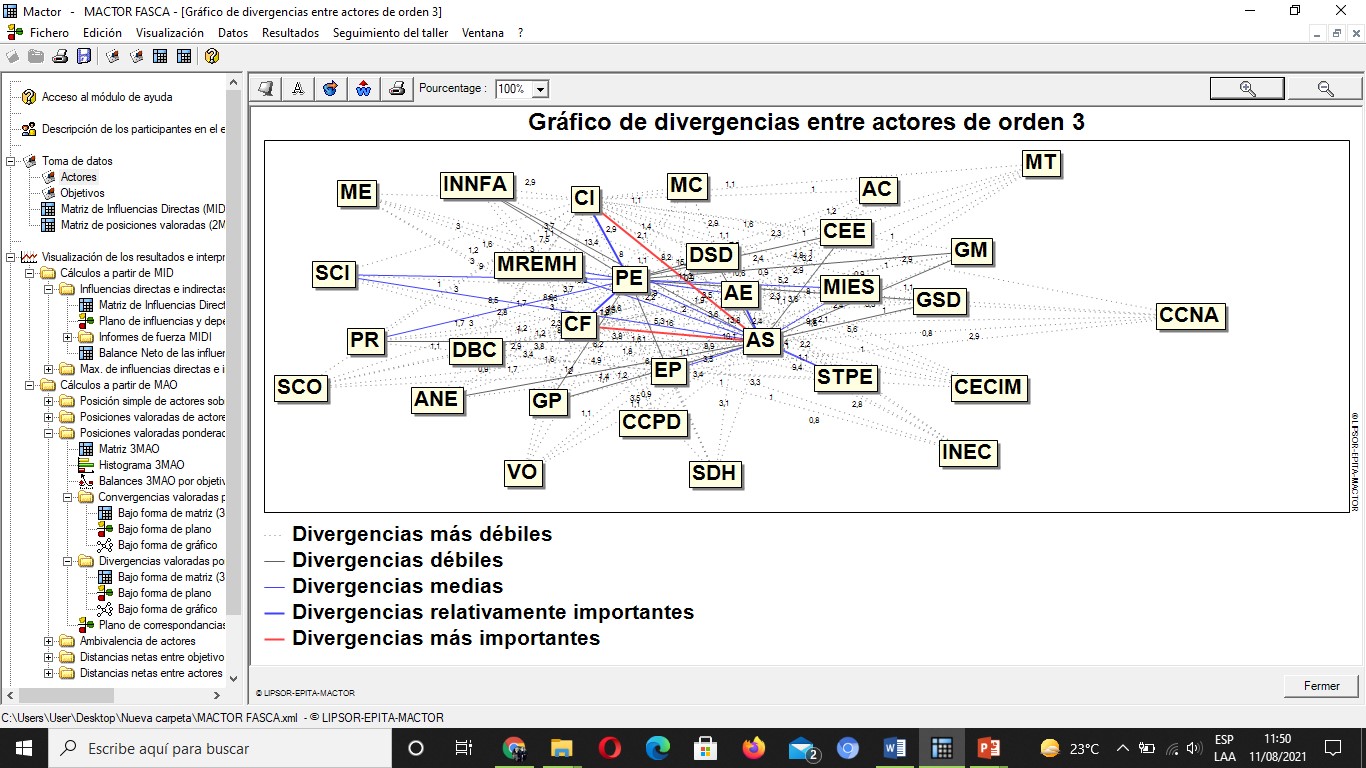

Regarding the alliances and conflicts between stakeholders, it was seen in the visual inputs in the network for convergences (figure 2) and divergences (figure 3) that the most important alliances include Cooperantes Fraternos, Cáritas Internacionalis, Strategic Allies and the Ministry of Human Relations and Human Mobility. Conversely, the highlighted conflicts include Cáritas Internacionalis, the Partner Assembly of Fundación de Acción Social Cáritas, Professionals external to Fundación de Acción Social Cáritas, and Cooperantes Fraternos. The alliances are constituted because the institutional missions, economic resources and human talent of the aforementioned stakeholders respond to a synergy caused by social aid purposes. The observed conflicts, in turn, reside in a dispute to obtain a bargaining power superior to that of the other stakeholders. Additionally, it is usual to see stakeholders that appear in the most decisive cases of both alliances and conflicts, when it comes to groups that have a Qi strength ratio higher than the average and display agreements and discrepancies in some of the future challenges.

By harnessing all the potential of the MACTOR method, not only do the exported graphs reveal the relationships in the form of lines of varying tone and intensity, but it is also possible to translate the alliances and conflicts using a numerical input known as degree of mobility. In this case study, the values for each future challenge have a positive degree of mobility (with the presence of agreements and disagreements) (Table 6). In other words, the selected stakeholders are not indifferent to the expected milestones for the system. Therefore, this guarantees that the social actors were chosen well and that the future challenges are not based on fantastical elements or exaggerated trends, since there is support for their achievement by some stakeholders, as well as minimal resistance to change from others.

Table 6 Synthesis of the strategic objectives towards 2035.

| N° | Stretegic objectives towards 2035 | Number of agreements | Number of disagreements | Grade of mobility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Increase the number of strategic allies by 50% | 64,4 | 0 | 64,4 |

| 2 | Increase the coverage capacity of the social services by 30% | 65,9 | -2,1 | 63,8 |

| 3 | Invest a total of $200.000 USD in technology capital | 64,8 | 0 | 64,8 |

| 4 | Establish 2 programs or projects that contribute to the complementarity of health services | 62,7 | -2,1 | 60,6 |

| 5 | Reduce in 25% recovery fees for current programs and projects | 65,6 | -2,1 | 63,5 |

| 6 | Increase by 40% the economic donations received | 55,4 | -6,8 | 48,6 |

| 7 | Implement social marketing strategies that strengthen the institutional image | 75,2 | 0 | 75,2 |

| 8 | Create a list of collaborators with university studies and medical specializations | 73,3 | -0,3 | 73 |

| 9 | Design an original internal communication system for Fundación de Acción Social Cáritas | 58,6 | 0 | 58,6 |

Source: MACTOR Software version 5.1.2.

4. Conclusions

In this research, the main stakeholders for Fundación de Acción Social Cáritas were identified with a view to the year 2035. Thus, with the support of the Matrix of Direct Influences and the Matrix of Valued Positions, it was revealed that only the National Secretariat of Planning is considered as a liaison stakeholder. In other words, it is the only one with high levels of influence and dependence. Also, it was found that the stakeholders with the most power within the system are: Ministry of Foreign Relations and Human Mobility, Cooperantes Fraternos, Ministry of Social and Economic Inclusion, Cáritas Internacionalis and Strategic Allies.

The alliances and conflicts that the stakeholders of this NGO presented were established in relation to the nine strategic objectives or future challenges that were collectively defined. According to the results obtained, all the challenges for the future have positive and high grades of mobility. This will allow Fundación de Acción Social Cáritas to undergo needed organizational development with the support of the main stakeholders in the system in a period of 15 years. To achieve the desired future it is necessary to keep moving forward with the prospective process. That is, the NGO needs to take advantage of the inputs obtained and recorded through the MICMAC and MACTOR methods to build alternative scenarios that, at a later stage, could contribute to the design of formal strategies for institutional progress.

Finally, it is recommended to use participatory methods for the construction of alternative scenarios, as well as to rely on an exploratory approach to contemplate futures that reflect favorable and adverse conditions. The NGO may be able to respond strategically to events of various kinds of this. Additionally, the implementation of a balanced scorecard of the first and second level is beneficial to evaluate through KPIs the short-, medium- and long-term objectives that will lead to the desired organizational state by Fundación de Acción Social Cáritas.