Introduction

Adolescent dating violence has been characterized as a public health issue since it is a risk factor for recurrent violent patterns in adult marital relationships, and it is also associated with a series of consequences for the mental health of the people involved (Barreira, Lima, & Avanci, 2013; Kim, Kim, Choi, & Emery, 2014; Smith, Ireland, Park, Elwyn, & Thornberry, 2011). Teen dating violence, adolescent relationship abuse or adolescent dating violence encompass a variety of abusive behaviors, including physical, psychological and sexual violence, found in the intimate relationships of preadolescents, adolescents and young adults (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Violence Prevention, CDC, USA, 2014; Mulford, & Blachman-Demner, 2013). Abuse can be direct, performed online over the internet, or even inflicted by a third party sent by the perpetrator (CDC, USA, 2014).

The research aimed at investigating violence in affective-sexual relationships among adolescents and young university students is recent in Brazil (Aldrighi, 2004; Marasca & Falcke, 2015; Minayo, Assis, & Njaine, 2011). An 86.8% rate of perpetrated dating violence was observed (Oliveira, Assis, Njaine, & Oliveira, 2011) in a study with 3,205 adolescents from 10 Brazilian capitals. In a survey conducted in Recife (PE), 83.9% of adolescents (n=408) aged 15-19 years claimed to have perpetrated and endured dating physical or psychological violence (Barreira, Lima, Bigras, Njaine, & Assis, 2014).

This phenomenon has also been extensively investigated in international studies. In a North American study with young people aged 11-16 years, 40% of the participants reported having perpetrated one or more abusive acts against their boyfriend/girlfriend, while 49% reported having suffered violence from their boyfriend/girlfriend (Goncy, Sullivan, Farrell, Mehari, & Garthe, 2017). In Italy, 43.7% of female adolescents and 34.8% of male adolescents declared having experienced some type of violence from their intimate partner (Romito, Beltramini, & Escribà-Agüir, 2013). In Portugal, a 25.4% victimization rate was found in a sample of young people aged 13-29 years (Caridade, 2011). In Mexico, university students reported 73% of psychological violence and 27.7% of sexual violence perpetrated by their intimate partner (Flores-Garrido & Barreto-Ávila, 2018).

Concerning the dating violence perpetration patterns, young males tend to show higher rates of sexual violence (Rey-Anacona, 2017; Wincentak, Connoly, & Card, 2017), while young females tend to perpetrate more physical or verbal/emotional violence (Abilleira, Rodicio-García, Vázquez, Deus, & Cortizas, 2019; Barreira et al., 2014; Borges, 2018; Marasca & Falcke, 2015). Considering the gender variable, a study that investigated models of the association between the use of violence and victimization in the relationships of Colombian adolescents, observed that adaptation problems are related to inflicting violence among men, and these are associated with victimization in women (Rozo-Sánchez, Moreno-Méndez, Perdomo-Escobar, & Avendaño-Prieto, 2019). Thus, although a two-way dating violence pattern can be seen, gender bias is observed in the types of violence perpetrated by adolescents.

There is a concern not only with the prevalence of youth dating violence rates but also with the consequences for mental health associated with its occurrence (Bonomi et al., 2013; Goncy et al., 2017). Several psychological problems, including symptoms of depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress, eating disorders, alcohol and tobacco use, and risky sexual behavior, have been associated with dating violence (Bonomi et al., 2013; Ulloa & Hammett, 2016). Both adolescent dating victimization and violence perpetration were associated with suicidal ideas and behaviors (Caridade & Barros, 2018).

Recent studies have indicated that adolescent dating violence is a multi-causal phenomenon, and several factors are associated with its occurrence (Baker, 2016; Choi, Weston, & Temple, 2017; Ouytsel et al., 2017; Sabina, Cuevas, & Cotignola-Pickens, 2016). A meta-analysis study (n=15 studies) indicated individual, family, and peer group variables as dating violence predictors (Gracia-Leiva, Puente-Martínez, Ubillos-Landa, & Páez-Rovira, 2019), Substance use, male sex as sexual violence perpetrators, group of aggressive peers, suffering or performing bullying, violence in the family of origin, and negative relationships between parents and children were associated with inflicting dating violence. In the literature review study (n=20 studies) proposed by Vagi et al. (2013), both risk and protective factors for the perpetration of dating violence were identified. The authors found 53 risk factors (individual and contextual), including greater acceptance of violence, violent peer group, substance use, childhood physical abuse, exposure to parental violence, and conflicting parent-child interaction, among others.

Furthermore, concerning individual variables, being female, showing greater acceptance of violence within intimate relationships, and having parents with lower educational levels were also associated with dating violence when compared to adolescents with no history of this type of violence (Choi et al., 2017). In their study, conducted with 1,042 adolescents from U.S. public schools, these authors found that being female was one of the predictors of dating violence (Choi et al., 2017). The meta-analysis carried out by Wincentak et al. (2016), with 101 studies, indicated that 25% of girls and 13% of boys had perpetrated physical violence during dating. In a study with Spanish adolescents, Izaguirre and Calvete (2017) found that girls were more characterized as both perpetrators and victims of psychological dating violence when compared to boys.

Another individual variable associated both with perpetrating and being a victim of violence in intimate relationships is the use of alcohol and other drugs (Baker, 2016; Facundo, Almanza, Rodríguez, Robles, & Hernández, 2009; Novak & Furman, 2016; Ouytselet al., 2017; Sabina et al., 2016). A study with American adolescents found that alcohol use was associated with being a perpetrator of dating violence (Novak & Furman, 2016). The influence of substance use on violence in romantic relationships was also observed in another North American study (Baker, 2016). A study conducted in Mexico with young people aged 18-29 years, found a significant relationship between alcohol use and psychological dating violence, indicating that the higher the alcohol consumption, the more serious the violence exerted by men against their girlfriends (Facundo et al. 2009).

Concerning contextual factors, exposure to domestic violence, whether by witnessing parents'marital violence, or being exposed to childhood abuse, has already been considered as a risk variable well documented in the international literature (Calvete, Fernández-González, Orue, & Little, 2018; Cascardi, 2016; Izaguirre & Calvete, 2017; Reyes et al., 2015). Izaguirre and Calvete (2017) found that witnessing parental violence in childhood predicts the perpetration of dating violence among young Spaniards.

A study with young university students in South Korea indicated that childhood physical abuse increased by 2.11 times the likelihood to perpetrate dating violence (Jennings et al., 2014). Reyes et al. (2015) indicated that suffering from childhood abuse was considered more relevant to dating violence than witnessing parental violence. Latin American studies (Martínez, Vargas, & Novoa, 2016; Moraga, Muñoz, Burgos, & Peña, 2019) have also found an association between domestic violence and dating violence. In Colombia, a study by Martinez et al. (2016) indicated that 43.5% of young people who had witnessed parental violence were victims of some type of intimate partner violence. In Chile, exposure to parental violence (Moraga et al., 2019), especially from the father against the mother, was associated with intimate partner violence in university students.

Studies highlight the presence of intergenerational transmission of violence in cases of dating violence (Faias, Caridade, & Cardoso, 2016; Karlsson, Temple, Weston, & Le, 2016). These studies are based on the assumptions of Social Learning Theory (Bandura, 1971; Bandura, Azzi, & Polydoro, 2008), in which violence is learned through vicarious observation and imitation, so that young people growing up in violent families repeatedly observe models, such as parents resolving marital conflicts through violence. Thus, these adolescents are more likely to accept the use of violence in intimate relationships (Karlsson et al., 2016; Smith et al., 2011).

Another contextual factor associated with adolescent dating violence is peer group influence (Ellis, Chung-Hall, & Dumas, 2013; Foshee et al., 2013; Santos & Murta, 2016), according to which young people who have friends that exert violence in intimate relationships or trivialize it, tend to be perpetrators of violence in their relationships. In a longitudinal study carried out with 3,412 North American adolescents from public schools, peer group influence was observed for the occurrence of dating violence. The results of this study indicated that having friends who exerted violence in their intimate relationships, being female, and being a "popular" teenager in their social environment increase the risk for dating violence (Foshee et al., 2013). A study with 589 Canadian adolescents identified that having friends in a peer group with aggressive behavior is a risk factor for victimization and perpetration of teen dating violence (Ellis et al., 2013).

In the Brazilian context, studies have pointed out the association between domestic violence and perpetration of physical and psychological violence in adolescent dating (Barreira et al., 2013; Oliveira et al., 2014). Marasca and Falcke (2015) investigated the role of the family and the peer group as predictors of dating violence. However, there is still a gap in the literature regarding the joint investigation of individual (gender and alcohol use) and contextual (family and peer group) factors that contribute to exerting violence in the intimate relationships of adolescents. From these initial considerations, this study aimed to investigate the presence of personal and contextual variables associated with the perpetration of adolescent dating violence.

Method

Participants

The sample of 403 youth who participated in this descriptive, cross-sectional study, were selected by convenience and reported having perpetrated some type of violence in affective-sexual relationships during adolescence (62.4% female, M=16.73 years; SD=1.20). They were high school students from public (64.5%), private (18.2%) and professional (17.3%) schools, from the Metropolitan Region of Porto Alegre, Brazil. Most adolescents came from nuclear families (54.2%), followed by single parents (26.5%). The inclusion criteria were being between 14-19 years old, and currently having some kind of love relationship or having had one in the past. Only adolescents who had experienced some type of (brief or stable) affective-sexual relationship throughout their lives or who were currently having a relationship ("hooking up with someone" and "dating") were included in the sample, whereas the cases of adolescents who declared being married or living with their partner were excluded. At the time of data collection, 63% of the participants had some type of affective-sexual relationship, with 31.4% "hooking up with someone" and 66.6%, dating. The duration of the relationship had been between two weeks and eight years (M=11.92 months, SD=12.90 months). The age of the current partner ranged from 13 to 30 years (M=17.81, SD=2.54). Among women, 91.9% reported having heterosexual and 8.1% gay relationships; and among men, 94.8% said they had heterosexual and 5.2% gay relationships.

Instruments

Sociodemographic questionnaire. The questionnaire was designed by the authors to assess individual characteristics (age, gender, schooling, use of alcohol and other drugs), relatives (with whom they lived, presence of marital violence between parents, use of drugs by relatives) and current or past sexual-affective relationships (the type of involvement, duration, data about the intimate partner). Two questions about peer group influence were included: "I have friends who verbally abuse their boyfriend/ girlfriend" and "I have friends who physically abuse their boyfriend/girlfriend". Being female, using alcohol, and having friends who verbally or physically abused the boyfriend/girlfriend were transformed into categorical variables of "1=yes" and "0=no".

Childhood abuse. The Exposure to Intrafamily Childhood Violence Inventory (IEVII), developed by the authors, was used to retrospectively assess the exposure to domestic violence suffered by adolescents throughout their childhood. The items of this instrument were developed from the literature, and three experts in the field acted as judges. There was good agreement between the judges on the proposed items and, subsequently, a pilot study was conducted (Borges, 2018).The inventory consists of 19 items, on a Likert scale ("0=never" and "3 =always"), which assess psychological abuse (8 items), neglect (4 items), physical abuse (4 items) and sexual abuse (3 items) perpetrated by parents or caregivers. The total score ranges from zero to 57 points. Subsequently, the data were coded as "0" for any type of childhood abuse, and as "1" for its occurrence for any type of exposure. In this study, the internal consistency analysis of the broad-scale was 0.83, and among the subscales, the consistency ranged from 0.50 (negligence) to 0.78 (sexual abuse).

Violence in adolescent affective-sexual relationships. The Adolescent Dating Relationships Inventory (CADRI, Wolfe, Scott, Reitzel-Jaffe, & Wekerle, 2001; adapted for Brazil by Minayo et al., 2011) was used, and it assesses the presence of abusive behavior in adolescent affective-sexual relationships, in situations where people are both victims and perpetrators of violence.

The instrument is answered using a Likert scale (0=never; 1 or 2 times=rarely; 3 to 5 times=sometimes; and more than 6 times=always), which investigates five types of violence (physical, sexual, psychological verbal/emotional, psychological/threats, and relational violence). In the study of the version adapted for Brazil (Minayo et al., 2011), Cronbach's alpha for the violence suffered was 0.87 and 0.88 for the perpetrated violence. In the current survey, Cronbach's alphas were 0.87 for perpetrated violence and 0.90 for suffered violence. Subsequently, a total score for victimization and another for the perpetration of violence were measured, where non-occurrence was coded as "zero" and "1" was coded for the occurrence of violence.

Procedures

Data were retrieved collectively, in public and private schools in the Metropolitan Region of Porto Alegre, after initial contact with the State Education Secretariat and the Administration of the schools. The selection of schools was by convenience sampling, following approval of the project by the State Education Secretariat. An initial rapport was established for the application of the research protocol. Data collection was carried out by psychologists and members of the research group.

To collect data, parents or legal caregivers of adolescents under 18 years old were asked to sign the Informed Consent Form (ICF), and the adolescents signed the Informed Assent Form. Adolescents over 18 years of age signed the ICF. The Psychology Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul approved this study (Opinion 1.143.563).

Data analysis

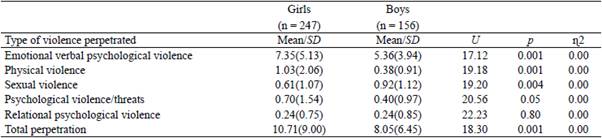

Descriptive and inferential statistical analyses were performed. Initially, descriptive analyses of participants, and variables of interest were performed (mean and standard deviation of CADRI scores, simple frequency of dating violence types). Considering that the variables did not show a normal distribution, a Mann-Whitney test was performed to verify the difference between the patterns of dating violence perpetration by gender. The Eta-Squared (ɳ.2) was used as a measure of effect size, based on the classification proposed by Cohen (1988) to interpret the magnitude of the effect size: 0.01=small, 0.06=medium, and 0.14=large.

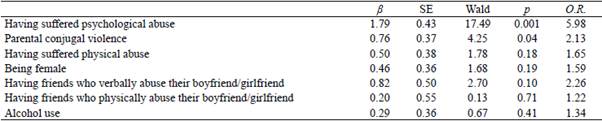

Subsequently, bivariate logistic regressions were performed to investigate predictors that increase the likelihood of adolescents being verbal/emotional violence perpetrators (0-no; 1-yes), using the Enter estimation technique. Verbal/ emotional violence was chosen for this analysis, as previous studies indicate that it is the type ofviolence most perpetrated by adolescents in their intimate relationships (Barreira et al., 2013; Oliveira et al., 2014).Thus, the independent variables used in the analysis were: witnessing parent marital violence (0-no; 1-yes); having suffered physical (0-no; 1-yes) and psychological (0-no; 1-yes) abuse in childhood by parents or caregivers; having friends who physically (0-no; 1-yes) and psychologically (0-no; 1-yes) abuse their boyfriend/ girlfriend; being female (0-no; 1-yes) and alcohol use (0-no; 1-yes). The values proposed by Wilson (2010) for the interpretation of logistic regression (Odd Ratio) were adopted: 1.50=small, 2.50=medium, and 4.30=large. The variables that were significant predictors of the perpetration of dating verbal/emotional violence were tested in a multivariate logistic regression model.

Results

Concerning the violence perpetrated, the results showed that verbal-emotional psychological violence (92%) was the most frequent, followed by sexual violence (37.0%) and physical violence (27%).

A significant difference was observed in the mean CADRI scores by gender (Table 1). The Mann-Whitney test indicated that female adolescents exerted more verbal/ emotional psychological violence, physical violence, and psychological violence/threats, while male adolescents inflicted more sexual violence, with small sizes of effect.

The results indicated that more than half (59%) of the adolescents reported experiencing some type of "verbal conflict" between their parents. About 8% of adolescents reported witnessing physical violence between their parents, and 6% using threats. Regarding childhood abuse exposure, 95.3% of adolescent perpetrators reported having suffered some type of violence from parents or caregivers, 94% informed having suffered psychological abuse, and 75.2% declared having suffered physical abuse.

Regarding the influence of peer groups, 28.5% of the participants reported knowing some friend who was experiencing some type of dating violence. Furthermore, 48.6% of adolescents identified that their friends were jealous of their boyfriend/girlfriend, and 14.1% reported having friends who physically abused their boyfriend/girlfriend. Regarding dating verbal abuse, 27.5% of the adolescents reported having a friend who perpetrated this type of violence.

Logistic Regression Analysis

Table 2 reports the results of bivariate logistic regressions, indicating the predictive variables of teenage dating verbal/emotional violence. It is observed that having suffered psychological abuse during childhood increases 5.98 times the likelihood of being a perpetrator of adolescent dating verbal/emotional violence while being exposed to parental violence increases 2.13 times this likelihood. The other variables were not significant in the model.

Subsequently, multivariate logistic regression was performed, in which only the variables having suffered childhood psychological abuse and having been exposed to parental violence in childhood were included in the model. The results showed that only having suffered childhood psychological abuse remained significant in the model: B=[1.68], SE=[0.43], Wald=[15.02], p=0.001. The estimated Odds Ratio indicated a higher likelihood [Exp (B) = 5.37, 95% CI (2.30-12-57)] to display verbal/emotional violence when the adolescent had suffered childhood psychological abuse. The model explains 9% (Nagelkerke R2) of the perpetration of adolescent dating verbal/emotional violence and correctly classifies 92.1% of cases. The variable having been exposed to conjugal violence was not significant in the model.

Discussion

Violence in adolescent affective-sexual relationships has been described as a serious public health issue associated with several triggering factors, characterizing the complexity of the theme and its multi-causal nature. Given this, different studies focus only on one variable or context of development, for example, exposure to domestic violence (Izaguirre & Calvete, 2017; Karlsson et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2014; Reyes et al., 2015), peer group (Ellis et al., 2013; Foshee et al., 2013), or drug use (Baker, 2016; Facundo et al., 2009). Few studies have emphasized more than one predictor of dating violence (Gracia-Leiva et al., 2019; Maraska & Falke, 2015; Oliveira et al., 2014).

Thus, this study aimed to enhance the understanding of factors associated with the perpetration of dating violence, considering two important developmental contexts for adolescents, namely, family and peer groups. Moreover, individual characteristics such as gender and alcohol use were considered as predictive variables. Therefore, this research expands and contributes to the area since it has an innovative character in investigating the influence of the main contexts of adolescent development in a single study.

Concerning violence perpetration patterns, the results indicated that 93% of the total sample of adolescents had already perpetrated some type of dating violence, whether physical, psychological-verbal, psychological-threat, relational, or sexual. When comparing the results of dating violence perpetration with previous Brazilian studies that also used CADRI, it can be observed that data found in this study were more severe than those with adolescents from Recife (PE) (83.4%, Barreira et al., 2014) and in ten Brazilian capitals (86.8%, Oliveira et al., 2011).These figures are also higher than those found in other countries, such as Italy (43%, Romito et al., 2013), Portugal (25.4%, Charity, 2011), Spain (24.5 %) and the United Kingdom (31%, Viejo, Monks, Sánchez, & Ortega-Ruiz, 2015). However, it is important to emphasize that the prevalence data depend on the conception of dating violence and the instruments adopted (Borges & Dell'Aglio, 2017; Shorey, Cornelius, & Bell, 2008). Furthermore, social and cultural aspects of the developmental context of the adolescents in this study, from the southern region of Brazil, characterized by more rigid cultural issues, especially regarding gender and patriarchal culture, should be considered. Stereotyped and violence-legitimizing gender norms are cited as aspects of the cultural context strongly linked to adolescent dating violence (Oliveira, Assis, Njaine, & Pires, 2016; Martínez et al., 2016).

Table 2 Binary logistic regression for the perpetration of verbal/emotional violence in affective-sexual relationships (n=399)

Verbal/emotional psychological perpetration was the most frequent perpetration type (92%), similar to previous studies that used CADRI (Barreira et al., 2014; Marasca & Falke, 2015). Choi et al. (2017) argue that verbal/emotional violence can be a gateway or a risk factor for other types of violence. Reyes, Foshee, Chen, and Ennett (2017) point out that psychological violence is the most common among adolescents due to the greater permissiveness of this type of violence in our society when compared to other types, such as physical and sexual violence. Oliveira et al. (2011) affirm that verbal violence is a cultural issue, which is accepted in our society and is often reproduced as a form of communication among adolescents, which causes legitimacy for this type of violence.

The results also indicated a difference by gender concerning the type of perpetrated dating violence, and girls achieved results of greater dating psychological and physical perpetration, while boys had higher rates of sexual violence. Such results are consistent with national and international surveys (Abilleira et al., 2019; Izaguirre, & Calvete, 2017; Oliveira et al., 2014; Rey-Anacona, 2017).However, the need for a critical view of this difference is emphasized, since the intensity and motivations of the offenses vary between boys and girls (Giordano, Soto, Manning, & Longmore, 2010; Shorey et al., 2008). The violence perpetrated by girls is commonly related to jealousy, or as self-defense of previously suffered violence (Shorey et al., 2008). A qualitative study with Mexican adolescents found that the perpetration of violence caused by female adolescents may be linked to verbal/psychological violence, including insults, blackmail, manipulation and control, associated with jealousy, lack of communication skills, distrust and betrayal (Pérez, Juárez & Cruz, 2019). Regarding the higher perpetration of sexual violence by boys, Oliveira et al. (2011) highlight rigid sexist and power patterns in love relationships, which contribute to a view that men can rape and abuse female bodies.

Previous studies (Calvete et al., 2018; Cascardi, 2016; Izaguirre & Calvete, 2017; Reyes et al., 2015) have pointed out that suffering from family violence is a risk factor for adolescent dating violence. The results of the current study confirm that having suffered from childhood psychological abuse is associated with the perpetration of verbal/emotional dating violence. In this sense, the results of this study reinforce the hypothesis of intergenerational transmission of violence, according to which, adolescents commonly become reproducers of behaviors learned in the family context and carry such learning into extra-family spaces, such as the intimate relationships (Faias et al., 2016; Oliveira & Sani, 2009). Dating violence can be understood as a result of intergenerational patterns of violence (Caridade, 2011; Jennings et al., 2014). Being a victim of childhood abuse in the family context can become a model for future violent interpersonal relationships, as violence is seen as a way of resolving conflicts (Faias et al., 2016; Jennings et al., 2014). New research can contribute to explaining the mechanisms by which violence is transmitted intergenerationally, considering the research findings on the acceptance of violence (Karlsson et al., 2016) and on cognitive mechanisms (initial maladaptive schemes, see Young, Klosko, & Weishaar 2008) that mediate the relationship between childhood abuse and adolescent dating violence (Borges & Dell'Aglio, 2019; Calvete et al., 2018; Cascardi, 2016). Moreover, different psychological variables associated with childhood abuse, such as, for example, insecure attachment in parent-child relationships, low frustration tolerance, and poor self-control (Jennings et al., 2014) must be further investigated, as they can mediate the association between childhood abuse and adolescent dating violence.

The results of dating violence studies may support the planning of public prevention policies. In this sense, early and preventive interventions with adolescents in situations of domestic violence (indicated prevention) become relevant, as these can be characterized as at greater risk for engaging in abusive intimate relationships. Specific violence prevention programs in adolescent dating are necessary to help youths recognize the presence of abusive behaviors in their love relationships and to learn ways to face conflicts without resorting to violence, thus breaking this cycle of violence. Recent studies evaluating intervention in dating violence already indicate that the improvement of assertive communication skills can be effective in reducing abusive behavior in the couple (Rey-Anacona, Martínez-Gómez, Castro-Rodríguez & Lozano-Jácome, 2020). Such intervention programs can be developed in a participatory manner in schools or the health network, with a language close to the adolescent population and, preferably, including peers, since previous studies point out that this approach is more effective (Santos & Murta, 2019). Furthermore, the relevance of preventive measures involving the family, especially the parents, is highlighted, given the association of family violence with dating violence.

This study has some limitations. A convenience sample was used, from the school context, in which there was a greater presence of female adolescents, which can bias the results found. Another limitation is the use of self-reporting instruments that can lead adolescents to give socially desirable responses. The experiences of violence suffered during childhood (abuse) were evaluated by a cross-sectional instrument that is based on the participants' memories (retrospectively).

It should also be noted that the use of the IEVII instrument is still being reviewed for validation, and only one reliability analysis was performed for this study (a=0.83 for the global scale). Furthermore, the results refer to the vision of only one of the adolescents of the dating dyad. Thus, new qualitative research with couple dyads is suggested for a better understanding of the dynamics of violence in adolescent affective-sexual relationships. The need for further longitudinal studies is also highlighted to investigate psychological and cognitive variables that contribute to the intergenerational nature of violence. As for the socioeconomic level, although the sample of this study included both private and public schools, the different contexts of incorporation of adolescents must be considered in more depth. Another aspect that should be highlighted is the need to investigate not only personal and family risk factors, but also protective factors, which can mitigate the impact of the risks, increasing the problem-solving options.

Despite the limitations mentioned, this study is innovative as it analyzed two contexts of adolescent development simultaneously (family and peer groups), as well as individual characteristics. Having suffered from childhood psychological abuse was associated with the perpetration of dating verbal/emotional violence, which supports the hypothesis of generational transmission of dating violence, considering that intergenerationality is not a risk factor per se, but a mechanism by which violence remains across generations. The study contributes to providing supporting elements for preventive interventions in situations of dating violence and broadens the debate on this event in Brazilian and international settings.

text in

text in