Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Universitas Psychologica

Print version ISSN 1657-9267

Univ. Psychol. vol.11 no.4 Bogotá Oct./Dec. 2012

Urgent Work: Developing a Gender-Responsive Approach for Girls in the Juvenile Justice System

Trabajo urgente: desarrollando una respuesta con perspectiva de género para niñas en el Sistema de Justicia Juvenil

Lawanda Ravoira *

Delores Barr Weaver Policy Center, Jacksonville, Florida, United States

Juliette Graziano **

Banyan Health Systems, Florida, United States

Vanessa Patino Lydia ***

Delores Barr Weaver Policy Center, Jacksonville, Florida, United States

* Delores Barr Weaver Policy Center, Jacksonville, Florida, United States. DPA. President and CEO, Delores Barr Weaver Policy Center, 1022 Park Street, Suite 301, Jacksonville, FL. 32204. E-mail: lravoira@thevoiceforgirls.org. ResearcherID: Raviora, L., H-1899-2012

** Banyan Health Systems, Florida, United States. PhD. Senior Director of Grants and Research Enrichment, Banyan Health Systems. E-mail: jgraziano@spectrumprograms.org. ResearcherID: Graziano, J., H-1757-2012

*** Delores Barr Weaver Policy Center, Jacksonville, Florida, United States. MPA. Director of Research and Planning, Delores Barr Weaver Policy Center, 1022 Park Street, Jacksonville, FL. 32204. E-mail: VPatino@nccdglobal.org. ResearcherID: Patino-Lydia, V., H-1677-2012

Recibido: mayo 1 de 2012 | Revisado: julio 10 de 2012 | Aceptado: julio 31 de 2012

Para citar este artículo:

Ravoira, L., Graziano, J. & Patino-Lydia, V. (2012). Urgent work: Developing a gender-responsive approach for girls in the Juvenile Justice System. Universitas Psychologica, 11(4), 11671181.

Abstract

This paper reviews the prevalence of girls in the U.S. juvenile justice system, compares national and international incarceration rates, and reviews the profile needs of justice-involved girls. The authors offer their Model as an example of how to develop a gender-responsive approach to girls in the justice system, including a description of how the model was operationalized in a community in the United States. Critical developments and emerging opportunities for each of the Model's components: advocacy, model programming, public education, training and technical assistance, gender responsive tools, systems accountability, and evaluation are highlighted. Lessons learned are offered as a springboard for conversations about how the international community can individually assess their needs and resources and work together to improve the response to girls. The paper concludes with recommendations for choosing, evaluating, and implementing best-practice approaches for meaningful reform.

Key words authors: Gender Psychology, Juvenile Justice, Girls.

Key words plus: Gender-Responsive Model, Gender-Responsive Best Practices, Florida Girls.

Resumen

Este artículo revisa la prevalencia de niñas en el Sistema de Justicia Juvenil de Estados Unidos, compara las tasas de encarcelamiento nacional e internacional y examina las necesidades de un perfil de las niñas involucradas. Los autores ofrecen su modelo como ejemplo para desarrollar una aproximación dirigida al género femenino en el Sistema de Justicia, incluyendo una descripción de su operacionalización en una comunidad de los Estados Unidos. En los desarrollos críticos y la emergencia de oportunidades para cada uno de los componentes del modelo, se destacan: la promoción legislativa y las políticas, el modelo de programación, la educación pública, la capacitación y asistencia técnica, las herramientas sensibles al género, los sistemas de responsabilidad y la evaluación. Las lecciones aprendidas se presentan como plataforma para la interlocución sobre la manera en que la comunidad internacional puede, en forma individual, evaluar necesidades y recursos, y trabajar conjuntamente para dar una mejor respuesta a las niñas. El artículo concluye con recomendaciones para escoger, evaluar e implementar mejores prácticas para una reforma significativa.

Palabras clave autores: Psicología de Género, justicia juvenil, niñas.

Palabras clave descriptores: Modelo de responsabilidad de género, mejores prácticas de responsabilidad de género, niñas de Florida.

SICI: 2011-2277(201212)11:4<1167:UWDGRA>2.0.CO;2-9

Everything started with the death of my grandma. That's when I started getting into trouble. What would have helped me? Somebody being there to understand what I was going through. I was all alone. There was no one left who cared about me after my grandmother died.

—Melissa (age 16, incarcerated)

Introduction

Melissa was abandoned by her father; her mother was addicted to drugs and unable to care for her. At a young age, she was molested by her mother's boyfriend and placed by the child welfare system into her grandmother's custody. Her grandmother was the only person who Melissa felt really cared about her.

When Melissa was 14 years old, her grandmother passed away. With no other family member willing to give her a home, Melissa was placed in the state foster care system. She felt like she was "living in a house of strangers" where no one understood or cared about her. She missed her grandmother and would often cry herself to sleep. She felt angry, confused, and alone. Over the next year, Melissa ran away from her foster home and started fighting in school and shoplifting at the local food markets. By age 15, she had received a battery charge for hitting the principal. She was sent to several alternative schools, where she continued to fight. Melissa was never provided with counseling or any services to address the multiple traumas in her life—the abandonment by her mother and father, the molestation, and the death of her grandmother.

Melissa's behaviors continued to escalate. When she was 16, while skipping school, she "went along" with a boyfriend when he robbed a local store. She stayed in the car while the robbery took place. When they were both arrested by the local police, Melissa was charged with robbery and placed in a detention facility.

Melissa feels hopeless and afraid. On two occasions while incarcerated, she has attempted suicide. Someday, she would like to go to college.

Melissa's story is that of thousands of girls and young women in the juvenile justice system, young girls whose lives are often scarred by abuse, victimization, abandonment, and loss. Their cries are unheard; their pain is unseen; their anger, misunderstood; their needs, ignored.

This paper will first review the prevalence of girls in the U.S. juvenile justice system, compare national and international incarceration rates, and review the profile of justice-involved girls. Second, the authors will offer their our model as an example of how to develop a gender-responsive approach to girls in the justice system, including a description of how the model was operationalized in a community in the United States. The model and lessons learned are offered as a springboard for conversations about how the international community can work together to improve the response to girls. The paper concludes with recommendations for choosing, evaluating, and implementing best-practice approaches to serving girls in the juvenile justice system.

Background

Prevalence of Girls in the U.S.

Juvenile Justice System

Girls are the fastest-growing segment of the juvenile justice population in the U.S. (American Bar Association & National Bar Association, 2001). A one-day snapshot in 2006- revealed that there were 13.943 girls incarcerated across the U. S. Nationally, girls represent 15% of the incarcerated population, which rises as high as 34% in some states. Since 1997, there has been an 18% decrease for boys who are incarcerated, compared to only an 8% decrease for girls (Sickmund, Sladky & Kang, 2008).

International Comparative Data

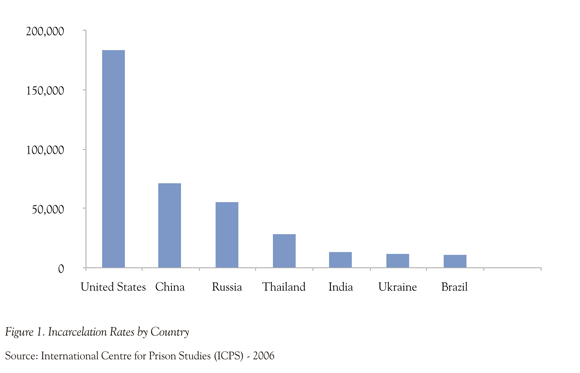

In 2006, the International Centre for Prison Studies (ICPS) released a report that calculated the number of girls and women in 187 prison systems in independent countries as well as dependent territories (Walmsley, 2006). The U.S. has the highest number of girls and women in prison: 183.400 (Figure 1). The countries that incarcerate the most girls and women include China (71.286), Russia (55.400), Thailand (28.450), India (13.350), Ukraine (11.830), and Brazil (11.000). According to the ICPS, incarcerated females generally make up between 2% and 9% of the general prison population.

Profile of Girls in the U.S. Justice System

Girls and young women present with complex physical, emotional, psychological, and familial issues related to histories of trauma, victimization, and abuse. To develop meaningful services and improve long-term outcomes for girls, it is imperative to understand who these girls are and what has led to their justice system involvement.

Through careful review of nearly 1.000 cases, combined with 200 interviews with girls in the system, NCCD transformed the conceptual understanding of justice-involved girls by creating a more accurate picture of system-involved females (Acoca & Dedel, 1998). The research revealed that girls reported extremely high rates of victimization, widespread school failure, physical and emotional health needs, substance use, and family problem Another study conducted by NCCD (Patino, Ra-voira & Wolf, 2006) as well as numerous other research has confirmed these findings, showing that substance use, mental health issues, abuse, and family issues such as parent incarceration are salient factors contributing to girls' delinquency (Zahn, Hawkins, Chiancone & Whitworth, 2008).

Intergenerational Consequences

of Girls' Incarceration

Intervening with girls is especially important because of the risks associated with intergenerational incarceration. If girls continue to be involved in the justice system throughout their lives, there are serious implications for their family members, children, community, and subsequent generations. When interventions focus on punishment, failing to address the needs of girls and the underlying trauma that is often the root of the delinquent behavior, a host of problems may continue uninterrupted. These problems include poor physical, emotional, and mental health; substance abuse; and future arrests and incarceration ("Girls in the Juvenile Justice System", 2009). The social costs are amplified exponentially given that these issues often follow girls into adulthood. Without appropriate interventions, these girls are at a high risk of domestic violence and becoming engaged in other violent relationships; dysfunctional parenting; and losing custody of their children, which perpetuates the cycle of intergenerational abuse, victimization, and incarceration (Belknap & Holsinger, 2006). Delinquent girls are more likely to heavily utilize public health and social welfare services in adulthood (Lederman, Dakof, Larrea & Li, 2004).

This paper presents a multifaceted, holistic, integrated model for how to both systemically and individually address the needs of justice-involved girls. This approach provides a foundation for reducing the risk factors while building on the strengths and resiliency of justice-involved girls. NCCD research shows that two out of three justice-involved girls (68%) wanted to continue education after high school, and 84% articulated long-term goals for the future (Patino et al., 2006). By addressing the needs of at-risk girls in a comprehensive, thoughtful manner on both the individual and system levels, we can provide them with the chance to succeed.

Model: A Gender-Responsive Model for

Girls in the Justice System

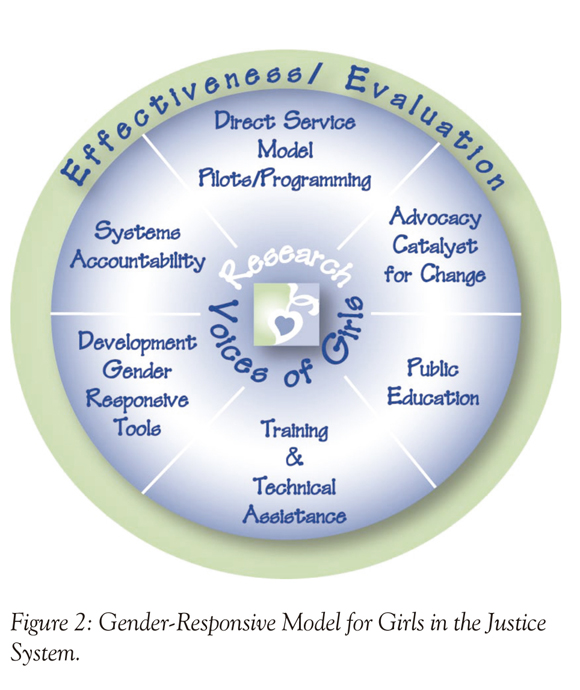

The authors haves developed a framework that can be used to create strategic plans for development and implementation of approaches to effectively address the gender-specific needs of girls and young women. In the U.S., current reform and intervention efforts are often piecemeal (e.g., individual-level or only focusing on one aspect of policy or one component of the continuum of services), and do not address practices and processes within local and state systems or individual programs. The model is designed to respond comprehensively to the disparate treatment of girls in the juvenile justice system.

This gender-responsive framework direct service, program, and system-level issues while maintaining an emphasis on advocacy and public education. At the core of the model are the voices of girls and a foundation grounded in research. The model recognizes that the development of gender-responsive tools and ongoing training and technical assistance are all critical components regarding how to effectively meet girls' needs and improve public safety. Finally, in order to ensure effectiveness, the model emphasizes systems accountability checks and formal and rigorous evaluation. The following section describes why each of the components is essential in serving at-risk girls, the critical developments and contributions that have been made in each of these areas, and current challenges.

Voices of Girls

- Context: The gender-responsive model recognizes that girls must be included in these efforts in order for our responses to be relevant and effective. Girls' voices provide a foundation to contextualize research, policy, and practice in order to prevent, intervene, and meet girls' treatment needs. Powerful insight into what is needed to serve girls can be gained from listening to what girls themselves have to say. Specific strategies for including girls' input can include facilitating individual interviews with justice-involved girls and conducting focus groups or surveys. Special attention must be paid to diverse representation of girls who are involved in prevention, detention, probation, and commitment services.

- Critical Developments: In 1990, the Valentine Foundation developed the essential elements of a gender-responsive approach, which included "giving girls voice in program design, implementation, and evaluation." Likewise, the Ms. Foundation for Women reiterates the importance of girls being actively involved in addressing their needs: "In safe space, staff and girls assess their needs together and staff responds to girls' needs with respect and understanding. Staff and girls jointly develop programs based on what they learn together. It is from this place of security that girls begin to re-envision themselves and engage their families, institutions, and communities in new and transforming ways". (Ms. Foundation for Women, 2001, p. 14) Much of the gender-responsive literature acknowledges that the inclusion of girls' voices, experiences, and participation is essential. This development has been an important step, since girls have historically been overlooked and dismissed by the justice system and by those charged with developing effective systems for intervention.

- Context: An emphasis on research is also at the core of the model. In order to effectively serve girls, we must have an accurate picture of what is getting them off track. We must be able to assess the challenges that staff face in working with girls, and the policies and practices that contribute to disparate or harmful treatment. We must generate a profile of girls' issues and needs and empirically test that these factors are related to their delinquency, as well as exploring factors at the individual, family, program, and system levels.

- Critical Developments: With the increasing number of girls entering the justice system, there has been a concomitant increase in the development of theories and research efforts to better understand the factors associated with girls' delinquency. Feminist theorists assert that gender-neutral theories, which focus on individual-level factors, "blame and pathologize girls instead of recognizing the roles that society and the criminal justice system play in girls' crimes" (Hubbard & Matthews, 2008, p. 232). More specifically, feminist theories argue that there are gender-specific considerations that the justice system and courts have historically ignored, including how relationships, experiences of abuse/victimization, and social location impact girls. Three particularly relevant theories include the feminist pathways, relational/ cultural, and intersectionality theories.

Research

—Feminist pathways theory posits that events during childhood, particularly trauma and victimization, are the antecedents of risk factors for female delinquency and crime (Foley, 2008), and are typically related to "histories of victimization, unstable family life, school failure, repeated status offenses, and mental health and substance abuse problems" (Bloom & Covington, 2001).

—Relational/cultural theory (RCT) emphasizes that growth and development take place through females' connections with others, which are influenced by the cultural contexts in which they occur. RCT also elaborates how damage can occur from disconnections that occur in relationships: in addition to the individual and family level, disconnection also occurs at the sociocultural level, which could lead to psychological difficulties such as isolation, shame, and silence (Jordan & Hartling, 2002).

—Intersectionality theory asserts that individuals can simultaneously occupy positions of privilege and oppression, depending on the reference group where gender, race, class, and sexuality create overlapping areas of advantage and disadvantage (Choo & Ferree, 2010). This theory acknowledges that while girls share similar experiences based on gender, there are also marked differences that are critical to understand and include in research—in particular, race/ethnicity and sexual orientation.

Collectively, these theories address the unique ways in which relationships and abuse and factors such as race, class, and sexual orientation impact adolescent female development and place girls at an increased risk of problem behaviors (Foley, 2008).

Research has consistently demonstrated that girls receive disparate treatment by the justice system compared to their male counterparts, which often results in policies and practices that negatively impact girls (Chesney-Lind & Shelden, 1998; Schaffner, 2006). Girls are disproportionately charged with status offenses and detained for longer periods of time than boys. The use of contempt proceedings and probation and parole violations make it more likely that girls will return to detention or a residential commitment program without having committed a crime (Sherman, 2005). Empirical evidence has clearly established that the increase in girls' arrests is partially due to society's response to girls' behavior, not necessarily an increase in girls' violence and aggression (Acoca & NCCD, 2000; Bloom, Owen & Covington, 2005; Lederman, 2000; Sherman, 1999). Moreover, many of girls' assault charges come from their activities within the system, such as fighting the arresting officer or acting out in detention or in a program (Roush, 1996). This is of significant concern, because girls' rates of recidivism are lower than those of boys, and girls generally do not pose a serious public safety threat.

Research also shows alarming rates of abuse and victimization, family dysfunction, substance use, negative peers, widespread school failure, and physical and mental health needs among delinquent girls (Acoca & NCCD, 2000; Patino et al., 2006). In comparison to boys, studies have shown, "abuse and neglect are more common, start earlier, and last longer for girls" (Belknap & Holsinger, 2006, p. 51). Research has documented that over 90% of incarcerated girls reported emotional, physical, and/or sexual abuse (Acoca & Dedel, 1998) and that girls report more family-related problems than boys, including parents who were involved in crime and difficult relationships with parents (Dembo et al., 1998; Funk, 1999). Substance use is extremely prevalent among justice-involved girls, who typically enter the juvenile justice system with higher rates of substance use disorders than boys (Teplin, Abram, McClelland, Dulcan & Mericle, 2002). Approximately 50% of girls report using drugs during the offenses that led to their incarceration (Fejes-Mendoza, Miller & Eppler, 1995). Association with deviant peers has been proven to be one of the strongest predictors of delinquency (Mears, Ploeger & Warr, 1998) and girls often report closer attachment and more intimate connections to peers than boys do (Giordano, Cernkovich & Pugh, 1986). The school-to-prison pipeline has been well-documented for males, and educational failure has been found to be the most statistically significant risk factor underlying girls' offending (Acoca & NCCD, 2000). Finally, research has shown that justice-involved girls have greater mental health needs than delinquent boys (Holsinger & Holsinger, 2005) and that over 90% of the justice system-involved girls had a diagnosed mental health problem (Office of Program Policy Analysis and Government Accountability [OPPAGA], 2005).

Justice-involved girls present alarming rates of high risk factors and behaviors, yet girls often do not get their treatment needs met while in programs (Chesney-Lind, Morash & Stevens, 2008). Staff often report feeling challenged by girls' behaviors and often confused about which approach is best (Gaarder, Rodriguez & Zatz, 2004). However, staff are clear that they want strategies and practical information that will enable them to experience success with girls.

Advocacy/Catalyst for Change

- Context: The advocacy piece of the model is aimed at engaging support from diverse stakeholders to change state statutes, policies, and practices that negatively impact girls, and to increase resources to enhance and expand gender-responsive services. Advocacy and change require development of strategic legislative agendas, including specific recommendations to address the identified needs of girls in the justice system in the context of the threat girls pose to public safety. Presenting testimony and collaborating with and other key stakeholders/partners is essential.

- Critical Developments: The first national-level recognition of the need to provide services designed to meet the unique needs of girls occurred in 1992, with the reautho-rization by the U.S. Congress of the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act of 1974. The reauthorization required states to prepare analysis and develop a plan for providing gender-specific services in the prevention and treatment of juvenile delinquency. Importantly, the JJDPA reauthoriza-tion introduced legislation that considered the intersectionality of risk factors for girls and also raised the issue of disproportionate minority confinement (DMC) to address the higher rates of youth minority incarceration.

OJJDP recommended the following guidelines when establishing services for girls (Greene, Peters & Associates, 1998):

—Programs should be all-female whenever possible;

—Girls should be treated in the least restrictive environment whenever possible;

—Programs should be close to girls' homes so as to help maintain family relationships;

—Programs should be consistent with female development and stress the role of relationship between staff and girls;

—Programs should be prepared to address the needs of parenting and pregnant teens.

These policy developments are important because they not only signal the problems that have plagued the justice system at a systems level but offer solutions at the system level.

Direct Service Model Pilots/Programming

- Context: At the heart of this work is the importance of implementing a continuum of care that includes prevention, early intervention, specialized treatment, and reentry and support services. It is imperative to provide appropriate support and services to mitigate the spiraling effects of the risk factors' leading to girls' involvement with the juvenile justice system. Programs offering academic and social service interventions are key, particularly ones that utilize community resources and specialized treatment with girls and families where problems already exist, keeping girls as close to home as possible. In service delivery, staff must value the developmental differences of girls and create a safe and supportive environment. Reentry and support services are critical for preventing recidivism among girls who are returning to their communities after having spent part of their adolescence behind bars.

- Critical Developments: One major step forward in this area has been to define the term "gender-responsive." Several definitions have been proposed. For example, Bloom et al. (2005) define gender-responsive as creating an environment—through site selection, staff selection, program development, content, and materials—that reflects an understanding of the realities of women's lives and address the issues of the participants. Gender-responsive approaches are multidimensional and based on theoretical perspectives that acknowledge women's pathways into the criminal justice system. These approaches address social (e.g., poverty, race, class, and gender) and cultural factors, as well as therapeutic interventions. These interventions address issues such as abuse, violence, family relationships, substance abuse, and co-occurring disorders. They provide a strengths-based approach to treatment and skills-building while emphasizing self-efficacy.

Other definitions include the following elements:

— Focus on providing comprehensive and relevant services which address girls' unique trajectories and needs in an environment that is respectful, honors and values girls and promotes positive gender identity development and empowerment (Girls Incorporated, 1996; Greene et al., 1998; Patton & Morgan, 2002).

In addition, scholars in the field have delineated the essential elements for working with girls, which include (1) using a comprehensive and individualized assessment process; (2) building a helping alliance; (3) using a gender-responsive cognitive-behavioral approach; (4) promoting healthy connections; and (5) recognizing within-girl differences (Matthews & Hubbard, 2008).

Public Education

- Context: The public is often uninformed or misinformed regarding issues that impact girls' justice-system involvement. For communities to come together and for stakeholders to understand the issues which affect at-risk girls, public education efforts need to articulate the problems as well as collaborative and reflective practices aimed at identifying effective solutions.

- Critical Developments: At the national, state, and local levels, public education campaigns are aimed at informing the public regarding the issues that impact girls' justice-system involvement. For example, at the national level, one of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration's objectives for their Trauma and Justice Initiative is to "build the public's awareness of the impact of trauma on health and behavioral health" (http://www.samhsa.gov/about/siDocs/traumaJustice.pdf ). This is crucial since the links between trauma and delinquency for girls are often unknown or poorly understood by the public.

At the state level, numerous states across the country have implemented gender-responsive approaches to working with girls in their justice systems. Locally, town hall meetings, conferences, and workshops about issues that impact justice-involved girls are occurring. For example, the issues of domestic and international human trafficking have recently received more attention and publicity. Documentaries have been aired on the major U.S. television networks, Congressional hearings have been convened in the U.S. Senate, and local communities have held town-hall meetings to raise awareness and identify local remedies.

Training and Technical Assistance

- Context: Staff charged with caring for girls often do not have a foundation regarding girls' pathways into the justice system and are uninformed regarding the definition of gender-responsiveness. Training must focus on how to work with girls, understanding gender differences, the profile of girls and what matters to them. There should be an emphasis on learning de-escalation techniques to ensure that girls do not, re-experience victimization, suffer emotional/ psychological abuse, and/or recidivate. Support for technical assistance that is individually tailored to the programs needs and staff skill sets is also critical.

- Critical Developments: Both government and non-government providers offer training and technical assistance for stakeholders who work with justice-system-involved girls. Some of these providers include the following:

—OJJDP's National Training and Technical Assistance Center;

—Training Curriculum for Managing and Supervising Justice-involved Girls (http://www.ncmhjj.com/pdfs/TrainingCurriculum.pdf);

—The Girl Matters comprehensive model developed by authors designed to integrate core concepts, theories, and practical interventions that promote a gender-responsive culture and build staff skill sets. This training challenges professionals to critically review the agency philosophy, policies, processes, programs, and services.

Gender-Responsive Tools

- Context: Gender-responsive tools are critical to accurately assessing girls' risk and needs, to assist decision makers with making decisions about what to do with girls, and even to assess the gender-responsiveness of a program or system.

- Critical Developments: Numerous tools have been created to initiate and support work with justice-involved girls. For example, curricula for use inside residential and other programs and protocols that assess the gender-responsiveness of programs have been developed, including the following:

—The VOICES curriculum, a multidimensional group intervention addressing trauma in adolescent girls, developed by the University of Connecticut;

—Juvenile Assessment and Intervention SystemTM (JAIS) by NCCD;

—Gender-responsive program assessment (Covington & Bloom, 2008);

—Gender-responsive protocol (NCCD).

Systems Accountability

- Context: Systems (juvenile justice, child welfare, education) must be held accountable regarding their treatment of girls. Too often, states and local jurisdictions operate under the status quo and do not have the resources to track and monitor dispositions by gender. States have been sued for physical and sexual abuse of children, institutional programs have been closed, and perpetrators have been sentenced. The authors advocate for all programs and services to institute practices that hold themselves accountable. This means organizations are transparent in all activities, making it clear there is align ment with serving the best interests of girls as opposed to other interests.

- Critical Developments: Today there are many organizations focused on tracking policies and practices affecting various issues of women and girls' lives, including Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and others. In the U.S., there has been a concerted effort to stop the shackling of pregnant women who are incarcerated.

- Context: Evaluation is essential. We must be able to test and determine the effectiveness of our interventions with justice-involved girls. This includes continually collecting data and information to inform and improve work with girls (to evaluate the impact of our public education efforts, direct service pilots, training curriculum, etc.), which has implications for replication.

- Critical Developments: Numerous gender-responsive programs have been developed in the past decade. The OJJDP Girls Study Group identified 61 girls-only programs. Of the 17 that had been evaluated, none met the criteria to be rated as effective (Zahn et al., 2008). Four programs were rates as "promising"; the rest had "inconclusive" or "insufficient evidence." Two key findings from the review of girls' delinquency programs were that more evaluations are needed and that many of these programs are no longer in existence, which suggests a lack of program sustainability.

Evaluation

Results: Operationalizing the Model

A Promising Model to Effect Change

In this section, we present a case study to illustrate the complexities of this work and how these components have been operationalized in one community in Florida. In "A Rallying Cry for Change" (Patino et al., 2006), NCCD researchers created a statewide profile of 319 girls in Florida juvenile justice system. In addition, NCCD partnered with the Children's Campaign, a citizen-led watchdog organization that advocates for proven strategies to improve outcomes for children. As a result of this research and partnership, a Girls Task Force was formed; a statewide Girls Summit was convened; a statewide conference on girls, "Faces of Courage," was convened; and a publication, "Justice for Girls: Blueprint for Action" (Ravoira, 2009), a model for the nation, was issued. At the local level, the community in Jacksonville, Florida, created the "Justice for Girls: Duval County Initiative." The following describes how the gender-responsive model was operationalized at the local level to affect change:

- Formation of a leadership council. A council of community leaders representing business, philanthropy, research, education, volun-teerism, and human rights was convened to serve as a coordinating body. The role of the council was to learn about local issues; provide pragmatic recommendations for change; and advance the goals and objectives using input from diverse stakeholders, including service providers, law enforcement, the state attorney, public defenders, judges, school personnel, child welfare, juvenile justice, parents, and justice-involved girls.

- Voices of girls and research. The leadership council conducted research to help develop a local profile of girls' issues, utilizing the voices of girls. NCCD created the profile by analyzing data from community agencies, the Florida Department of Juvenile Justice, schools, shelters, and girls' programs. After an intensive 12-month review of national, state, and local data as well as input from diverse stakeholders, the leadership council published "Justice for Girls: Duval County Initiative." The report outlined a two-pronged strategic plan for systemic change that entailed an advocacy strategy and the development of a local continuum of gender-responsive services.

- Public education, advocacy, and programming. During the next stage, the emphasis was on public education and advocacy for system-level change as well as the development of comprehensive programming and public education. With information gleaned from the research and input from key stakeholders, numerous presentations were given to school boards, founders, community stakeholders, and the state legislature. The advocacy platform includes promoting legislative and policy changes regarding overuse of violation of probation/non-law violations; misapplication of domestic violence statutes; overuse of detention; call for review of "charges caught" inside poorly functioning residential facilities; and a protocol for staff training. The local continuum-of-care section outlines specific programming initiatives to reduce out-of-school suspensions, diversion options, and a local staff secure residential facility (Ravoira, 2009).

Guided by this research, authors have responded by developing two programs:

- It's Elementary: This program offers school, community, and home interventions for elementary school girls at risk of suspension, while affecting school structures, policies, and practices, including staff training and tools to improve responses to girls who are displaying challenging behaviors.

- JAGS Detention: This program model connected girls placed in secure detention with community resources and advocates to divert them as quickly as possible based on individualized assessments. To support the staff, interns were recruited from local colleges and specially trained to provide care management services, groups, and recreational activities (yoga, meditation, visual arts, drama, skill-building activities, mentoring, etc.).

While the above-mentioned components of the model are critical, there need to be continued training and technical assistance as well as the means to ensure system accountability and evaluation to test the effectiveness of the components.

- Tools, training, and technical assistance: As part of these initiatives, the authors has used existing tools and training curricula and offered technical assistance, as well as creating new, individualized resources. The authors utilizes gender-responsive needs assessments and signature training curricula. In addition, a variety of tools have been created, and training and technical assistance modified as needed, to meet the specific needs of programs and respond to girls and practitioners.

- Systems accountability and evaluation: Regarding systems accountability, there have been several findings demonstrating system-level issues' negative impact on girls. Research conducted in the community, for example, revealed the number of girls suspended and the proportion of those girls who are minorities. In addition, the Florida Department of Juvenile Justice now reports the number of girls restrained and the number of girls who receive additional charges while in custody. As a result of these efforts, the training has been provided to contract monitors using the assessment tool developed by the authors to assess the level of gender-responsiveness of their programs. Evaluation of all components of the model is essential. For example, specific outcomes to measure competence, satisfaction, and the development of knowledge and skills are built into the programming.

Discussion and Recommendations

This review has documented the many contributions that have been made to date in order to effectively serve justice-involved girls. The gender-responsive model is offered as a thoughtful and deliberate framework for how strategies relate to and inform one other to assist us in our efforts to better serve girls. Internationally, communities can determine the usefulness of the model and its components regarding their own efforts.

There have been numerous critical developments for gender-responsive approaches that are opening up more opportunities. A few of these are outlined below:

- Opportunities for involving girls: Including the voices of girls allows us to learn from girls' experiences. Studies that include the voices of girls show common themes among justice-involved girls: girls often say they want someone to talk to; counseling services; academic, career, and health education; and independent living skills, among other things (Chesney-Lind et al., 2008).

- Opportunities for using research: There has been increased focus on research and building a body of empirical evidence regarding girls' high risk behaviors and delinquency. Research can inform direct services, public education campaigns, specialized training/ technical assistance, advocacy efforts, and evaluation. We must use approaches that incorporate relevant theoretical frameworks that (1) include factors that are the most salient in girls' lives and (2) are informed by research on both individual and system-level issues.

- Advocacy opportunities: The passage of gender-specific legislation has brought about an increase in public awareness, which has resulted in justice-involved girls becoming part of the legislative agenda. As a result, OJJDP funded the Girls Study Group to conduct research. In 2010, OJJDP funded the creation of the National Girls Institute to develop national standards of care, provide training and technical assistance, and serve as a clearinghouse of information and resources for stakeholders.

- Opportunities for gender-responsive programming and models: Numerous programs have been developed specifically for girls. These programs often take gender into account and target risk factors salient for girls. It is important to continue to build an evidence base of "what works" for girls. While gender-responsiveness has been defined and the critical elements have been outlined, we need to continue to test which components are most effective. Outcome evaluations and other rigorous research projects can empirically support gender-responsive approaches. With this information, we can continue to develop effective models for replication.

- Public education opportunities: By raising awareness, we can help mobilize citizens and stakeholders to engage in the development of services and opportunities for girls, including volunteers, tutors, mentors, job shadowing, employment, etc. The author's experience is that public awareness leads to active citizen engagement. Citizens who can collaborate and offer skills, expertise, time, and/or funding have often stepped forward in order to make a difference for girls.

- Training and technical assistance opportunities: There are numerous opportunities to provide training and technical assistance to service providers and stakeholders. The return on this investment includes increased staff satisfaction and skill sets, reduced staff turnover, and improved outcomes for girls. Feedback from training participants underscores what makes gender-responsive training different. In interviews and focus groups coordinated by the authors, staff felt they "(...) learned not only why gender matters but what we are doing well, what we need to change, and practical, cost-effective strategies for making the change" (comment from a Missouri detention supervisor in a training feedback survey).

- Opportunities for utilizing gender-responsive tools: Providers and stakeholders must demand tools that are responsive to the girls they serve. Currently, there are gender-specific risk and needs instruments as well as protocols to assess the gender-responsiveness of service delivery. If used widely, these tools can better inform administrators and decision makers about girls' needs, gaps in services, staff training needs, programs' performance, etc.

- Systems accountability: The authors are calling for the National Girls Institute to develop, national standards of care to improve responses to girls in the juvenile justice system. We need to ensure that our systems are not inflicting unintended harm. In addition, we need to be accountable for our approaches to serving justice-involved girls.

- Evaluation opportunities: With evaluations, we can rigorously test the outcomes of gender-responsive programs. Most programs target specific risk and protective factors as well as outcomes such as delinquency, substance use, and other high risk behaviors. For example, we can learn about which protective factors are most influential for which girls, as girls are not a homogenous group. This can help tailor programs to better serve specific populations.

Although numerous empirical, theoretical, policy, and intervention developments have been made regarding girls' delinquency, much work still needs to occur. The current gender-neutral approach to juvenile justice employed by most of the U.S. and the majority of the international community is not adequate. This is not just a domestic issue; it is an international concern.

The following tactical strategies are recommended as critical to the bringing about meaningful reform:

- Conduct research to develop an accurate profile of girls as a basis for the development of a strategic plan grounded in the needs of girls balanced with public safety needs;

- Identify and re-examine statutes, policies, procedures, and practices that shepherd girls into the system (e.g., impact of violations of probation or conditional release; domestic violence laws; use of detention; zero tolerance);

- Create a high-level prevention task force charged with identifying strategies, programs, and services to keep girls out of the system, including traditional juvenile justice decision makers such as district attorneys, police, judges, and service providers, as well as representatives from other systems that touch girls' lives (education, mental health service providers, churches, community-based programs, etc.);

- Determine points in the judicial process where girls could be diverted prior to formal intake into the system;

- Provide alternatives to secure detention for girls who do not pose a public safety or flight risk, including options such as home detention;

- Develop and adequately fund gender-responsive, community-based diversion and intervention options;

- Require gender-specific training for all justice professionals, including judges, state attorney, police, school resource officers, as well as service providers.

Melissa's story is a poignant example of the way girls fall victim to an inadequate system. By listening to the voices of girls like Melissa, distinct lessons can be learned and applied to improve the way girls locally and internationally interact with the juvenile justice system. We must change how we respond to girls and young women. It is vital to the health and well-being of our state and our local communities, and to the next generation of children. We need to listen to girls' stories so that all girls can have better opportunities and experiences, and a better future.

References

Acoca, L. & Dedel, K. (1998). No place to hide: Understanding and meeting the needs of girls in the California Juvenile Justice System. San Francisco: National Council on Crime and Delinquency. [ Links ]

Acoca, L. & National Council on Crime and Delinquency. (2000). Educate or incarcerate: Girls in the Florida and Duval County Juvenile Justice Systems. Oakland: National Council on Crime and Delinquency. [ Links ]

American Bar Association & National Bar Association. (2001, May). Justice by gender: The lack of appropriate prevention, diversion, and treatment alternatives for girls in the juvenile justice system (Report). William & Mary Journal of Women and the Law, 9(1), 73-97. Available at http://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmjowl/vol9/iss1/5 [ Links ]

Belknap, J. & Holsinger, K. (2006). The gendered nature of risk factors for delinquency. Feminist Criminology, 1(1), 48-71. [ Links ]

Bloom, B. E. & Covington, S. (2001, November). Effective gender-responsive interventions in juvenile justice: Addressing the lives of delinquent girls. Paper presented at the 53rd Annual Meeting of American Society of Criminology, Atlanta, GA. [ Links ]

Bloom, B. & Covington, S. (2008). Addressing the mental health needs of women offenders. In R. L. Gido & L. Dalley (Eds.), Women's mental health issues across the criminal justice system (pp. 160-176). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Bloom, B., Owen, B. & Covington, S. (2005). Gender-responsive strategies for women offenders: A summary of research, practice, and guiding principles for women offenders. Washington, DC: National Institute of Corrections. [ Links ]

Chesney-Lind, M., Morash, M. & Stevens, T. (2008). Girls' troubles, girls' delinquency, and gender responsive programming: A review. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology, 41 (1), 162-189. [ Links ]

Chesney-Lind, M. & Shelden, R. G. (1998). Girls, delinquency, and juvenile justice. Belmont, CA: West/ Wadsworth. [ Links ]

Choo, H. Y. & Ferree, M. M. (2010). Practicing inter-sectionality in sociological research: A critical analysis of inclusions, interactions and institutions in the study of inequalities. Sociological Theory, 28(2), 129-149. [ Links ]

Covington, S. (1998). The relational theory of women's psychological development: Implications for the criminal justice system. In R. Zaplin (Ed.), Female offenders: Critical perspectives and effective intervention (pp. 113-131). Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen Press. [ Links ]

Covington, S. & Bloom, B. (2008). Gender-responsive programming assessment. Retrieved February 21, 2011, from http://www.centerforgenderandjustice.org/pdf/GRProgramAssessmentTool%20CJ%20 Final.pdf [ Links ]

Dembo, R., Pacheco, K., Schmeidler, J., Ramirez-Garmica, G., Guida, J. & Rahman, A. (1998). A further study of gender differences in service needs among youths entering a juvenile assessment centre. Journal of Child and Adolescent Substance Abuse, 7(4), 49-77. [ Links ]

Fejes-Mendoza, K., Miller, D. & Eppler, R. (1995). Portraits of dysfunction: Criminal, educational, and family profiles of juvenile female offenders. Education and Treatment of Children, 18(3), 309-321. [ Links ]

Foley, A. (2008). The current state of gender-specific delinquency programming. Journal of Criminal Justice, 36(3), 262-269. [ Links ]

Funk, S. J. (1999). Risk assessment for juveniles on probation. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 26(1), 44-68. [ Links ]

Gaarder, E., Rodriguez, N. & Zatz, M. (2004). Criers, liars, and manipulators: Probation officers' views of girls. Justice Quarterly, 21(3), 547-578. [ Links ]

Giordano, P., Cernkovich, S. & Pugh, M. (1986). Friendships and delinquency. American Journal of Sociology, 91(5), 1170-1202. [ Links ]

Girls Incorporated & Office ofJuvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. (1996, June). Prevention and parity: Girls in juvenile justice (Report C010994). New York: Girls Incorporated. [ Links ]

Greene, Peters & Associates. (1998). Guiding principles for promising female programming: An inventory of best practices. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. [ Links ]

Holsinger, K. & Holsinger, A. (2005). Differential pathways to violence and self-injurious behavior: African-American and white girls in the Juvenile Justice System. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 42(2), 211-242. [ Links ]

Huang, L. (2010, October). Strategic initiative #2: Trauma and justice [Draft]. Available at Office of Behavioral Health Equity website: http://www.samhsa.gov/about/siDocs/traumaJustice.pdf [ Links ]

Hubbard, D. J. & Matthews, B. (2008). Reconciling the differences between the "gender responsive" and the "what works" literatures to improve services for girls. Crime and Delinquency, 54(2), 225-258. [ Links ]

Jordan, J. V. & Hartling, L. M. (2002). New developments in relational-cultural theory. In M. Ballou & L. S. Brown (Eds.), Rethinking mental health and disorders: Feminist perspectives (pp. 48-70). New York: Guilford Publications. [ Links ]

Lederman, C. (2000). Girls in the juvenile justice system: What you should know. ABA Child Law Practice, 19(7), 110-111. [ Links ]

Lederman, C. S., Dakof, G. A., Larrea, M. A. & Li, H. (2004). Characteristics of adolescent females in juvenile detention. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 27(4), 321-337. [ Links ]

Matthews, B. & Hubbard, D. J. (2008). Moving ahead: Five essential elements for working effectively with girls. Journal of Criminal Justice, 36(6), 494-502. [ Links ]

Mears, D. P., Ploeger, M. & Warr, M. (1998). Explaining the gender gap in delinquency: Peer influence and moral evaluations of behavior. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 35(3), 251-266. [ Links ]

Ms. Foundation for Women. (2001). The new girls movement: Implications for youth programs. New York: Author. [ Links ]

National Council on Crime and Delinquency. (2008). Juvenile Assessment and Intervention SystemTM (JAIS). Available at http://www.nccd-crc.org/nccd/dnld/JAIS%20brochure.pdf [ Links ]

Office of Program Policy Analysis and Government Accountability. (2005). Gender-specific services for delinquent girls vary across prevention, detention, and probation programs (Report No. 05-56). Tallahassee, FL: The Florida Legislature. [ Links ]

Patino, V., Ravoira, L. & Wolf, A. (2006). A rallying cry for change: Charting a new direction in the state of Florida's response to girls. Oakland, CA: National Council on Crime and Delinquency. [ Links ]

Patton, P. & Morgan, M. (2002). How to implement Oregon's guidelines for effective gender responsive programming for girls. Oregon: Oregon Criminal Justice Commission Juvenile Crime Prevention Program, Oregon Commission on Children and Families. [ Links ]

Ravoira, L. (2009). Justice for girls: Blueprint for action. Tallahassee, FL: Children's Campaign, Inc. Available at http://www.justiceforallgirls.org/advocacy/Bluprnt0109.pdf [ Links ]

Roush, D. W. (1996). Desktop guide to good juvenile detention practice. Washington, DC: Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. [ Links ]

Schaffner, L. (2006). Girls in trouble with the law. Piscataway, NJ: Rutgers University Press. [ Links ]

Sherman, F. (1999, October). The juvenile rights advocacy project: Representing girls in context. Justice Matters, 6(1), 29-30. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office ofJustice Programs, Office ofJuvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. [ Links ]

Sherman, F. (2005). Detention reform and girls: Challenges and solutions. Baltimore: The Annie E. Casey Foundation. Retrieved March 3, 2006, from http://www.aecf.org/publications/data/jdai_pathways_girls.pdf [ Links ]

Sickmund, M., Sladky, T. J. & Kang, W. (2008). Census of juveniles in residential placement databook. Washington, DC: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. Available at http://www.ojjdp.ncjrs.gov/ojstatbb/cjrp/ [ Links ]

Teplin, L. A., Abram, K. M., McClelland, G. M., Dulcan, M. K. & Mericle, A. A. (2002). Psychiatric disorders in youth in juvenile detention. Archives of General Psychiatry, 59(12), 1133-1143. [ Links ]

United States House of Representatives. Committee on the Judiciary. (2009, October). Girls in the juvenile justice system: Strategies to help girls achieve their full potential. One Hundred Eleventh Congress, Hearings before the Subcommittee on Crime, Terrorism and Homeland Security (Serial No. 111-77). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. [ Links ]

Walmsley, R. (2006, November). World female imprisonment list. London: International Centre for Prison Studies. Available at http://www.kcl.ac.uk/depsta/law/research/icps/downloads/women-prison-list-2006.pdf [ Links ]

Zahn, M. A., Hawkins, S. R., Chiancone, J. & Whit-worth, A. (2008, October). The girls study group-Charting the way to delinquency prevention for girls. Juvenile Justice Bulletin, 1-8. Washington, DC: U.S. Department ofJustice, Office ofJustice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. [ Links ]